View south from Till’s lookout toward Mt. Pirongia

View north from Till’s Lookout toward Hamilton

In a previous post about our experiences during New Zealand’s Level 4 Lockdown, we focused on how we adjusted to confinement within our two-person-household “bubble,” virtually connecting with family, friends, and our missionary cohort while avoiding close contact with anyone in the same physical space. But although we were locked out of the Matthew Cowley Pacific Church History Centre, locked out of church, and required to work at home, we didn’t necessarily have to stay at home. The closure of all but essential services such as grocery stores and healthcare clinics gave people fewer reasons to leave the house, but New Zealanders were encouraged to take advantage of the great outdoors—in their own neighborhoods, anyway—for their physical and emotional well-being.

We especially enjoyed beautiful sunrises like this

Crossing over the gully that runs through Dinsdale

The Midwifery Villa around the corner had to close during the lockdown

Bremworth Park

Lake Rotoroa at dusk

Our local “dairy” (aka convenience store) is just around the corner

Before the lockdown, we had established the habit of starting each day with a 30-minute walk around the neighborhood before getting ready to go to work. When we arrived in New Zealand, most of the North Island was suffering from a summer drought, so during our first few months here we rarely had to worry about getting wet when we went walking in the morning. Fair weather continued well into autumn, which had officially (if not meteorologically) begun just before the lockdown. Soon after our confinement began, when we realized that it was no longer imperative to be back home by 7:35 a.m. so we could shower, eat, and be ready to leave for the Centre by 8:45, we began lengthening our early-morning walks. Before long we were adding a 45-minute afternoon walk to our daily schedule because, well, why stay inside at a makeshift desk from 9 to 5 every day if you don’t have to? As the days shortened and the weather grew both cooler and rainier, our working-from-home situation allowed us to adjust our walking schedule accordingly. We could wait until the sun rose before going out in the morning, or we could stop work in the middle of the day to take advantage of a break in the rain.

The decorator of this yard would have gotten along really well with Michael’s Grandma Jones

We never knew that pigeon racing existed, let alone in our neighborhood

The ability to spend more time outside also allowed us to venture farther from home. Although the scenery around Frankton and Dinsdale isn’t in the same league with the bush-covered mountains, tumbling waterfalls, and rocky coastlines we’d seen elsewhere in New Zealand, we discovered some interesting and uniquely beautiful views within a couple of miles of our own flat.

Hamilton residents surely were among the first to begin participating in the international teddy bear hunt, instituted to give children who could no longer go to school or play with friends something to look forward to each day. A New York Times article published on 3 April featured some kids from Hamilton and the stuffed animals they had seen in neighbors’ windows. We played along with everyone else, photographing many of the bears and other creatures we passed during our walks. Sadly, we hadn’t thought to pack any stuffed animals in our missionary luggage, so Nancy drew a picture of a teddy bear, added an inspirational message, and posted it in our front window next to a picture of Jesus. It was fun to see people stop and point—and sometimes give a thumbs-up—as they passed our flat.

Our Neighborhood Teddy Bear Brigade

Our contribution to the bear hunt

One of the things we enjoyed most about our walkabouts during the lockdown was greeting other people along the way. While most seemed committed to keeping the required two-metres distance from everyone else, stepping off the footpath or crossing the street when we were in danger of passing each other too closely, most people seemed equally committed to being friendly. We were physically distancing ourselves, not socially distancing. Indeed, the lockdown brought a wonderful sense of community to New Zealand. People smiled at each other. Everyone said hello. We waved to people who were out working in their gardens or painting their fences or playing with their kids—and they waved back. We cheered for a child whose older sister was helping him learn to ride a bike. We gave a thumbs-up to a man who was teaching his son to use a lawnmower. Sometimes perfect strangers noticed our name tags and stopped to talk (at a safe remove, of course), curious about where we were from and why we were still here when most other Americans had gone home. When she had announced the lockdown and explained why it was necessary, Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern had reminded New Zealanders that “we are all in this together” and admonished everyone to “be kind.” Throughout the lockdown, it appeared that the entire country had taken that advice to heart, practicing “kia ngawari” (be kind, be gentle, be loving) as well as “kia kaha” (be strong).

Shelf-stable milk

On the other hand, going to the grocery store under Level 4 restrictions was not the most pleasant experience. We managed to avoid the need to shop for the first couple of weeks because, anticipating that we might not be able to go out for groceries for a while, we had stocked our pantry in mid-March (judiciously—no unnecessary stockpiling of toilet paper). We even purchased a few cartons of shelf-stable milk. Both of us had experienced nasty, warm, boxed milk while we were living in Europe in the 1970s (Michael on his first mission in Paris, Nancy on BYU Study Abroad in Madrid) so buying some now was a leap of faith, but Nancy convinced Michael that it was worth a try so we wouldn’t have to eat our muesli and bran flakes completely dry. To our surprise, New Zealand’s twenty-first-century version of shelf-stable milk isn’t bad at all. (Indeed, we’ve continued to buy it to save space in our tiny refrigerator.) Eventually, however, we had to replenish our food supply.

At first we tried ordering online to avoid the hassle—and risk—of going into a store. Pak ’n Save, New Zealand’s discount grocery chain, was already offering online ordering but now had to step up its “Click ’n Collect” program in response to the Level 4 lockdown. Users could reserve a pick-up time slot up to a week in advance, but because the service became so popular and locker space for fulfilled orders was limited, it was like trying to book tickets for a John Legend concert: you had to get up early to secure a slot.

Only one person at a time was allowed within the Click ’n Collect pick-up area

We picked up our first order a week after we placed it and were dismayed to discover that the bags in our locker contained neither the flour nor the eggs we had requested. Apparently, too many other people had ordered 3-kilo bags of flour and cartons of ten size-7 eggs ahead of us; thus we learned that we should not have checked the “no substitutions” box on the order form. Barry and Eva, who happened to drop by that day to leave something on our doorstep, told us that Countdown also was out of flour and reasonably-sized eggs, but offered to check New World for us since they had planned to go there, anyway. Although at that point the lockdown baking binge had just barely begun, finding flour for sale in anything smaller than a 20-kilo bag was even harder than obtaining toilet paper and hand sanitizer. We later learned that the problem was not a shortage of flour, but a shortage of small-size bags. The paper packages were manufactured in China, and New Zealand had put a hold on all shipments coming from there. (You may be asking: Why didn’t they just buy a 20-kilo bag? Well, we’ll tell you: We might have, had we had enough air-tight, roach-proof containers to keep the flour in after the bag was opened.)

When we were unable to obtain a Click ’n Collect time slot the next time we needed groceries, we realized that we would have to actually go shopping. Others had described the new realities: We should expect long lines to enter the store because only a limited number of people were allowed inside at once, and only one person per household—although we could get around that if we walked up to the entrance separately and acted like we didn’t know each other. We would not be able to take reusable bags into the store. We should not take a trolley (the Kiwi term for shopping cart) from the car park, but wait to get one with a disinfected handle from the attendant. We should use the hand-washing stations set up inside and outside the store before entering and again before leaving. We shouldn’t pick up anything unless we planned to buy it. And we should avoid getting too near any other shoppers or store employees.

Waiting, physically distanced, to enter the grocery store

Hoping that the line would not be too long if we went early in the morning, we made our first post-lockdown trip to Pak ’n Save before breakfast on 8 April, arriving at 7:10. Michael dropped Nancy off to get in line while he went to park. There were probably fifty people already strung out across the parking lot and down the street, waiting to get in. Nancy passed the time by chatting with the woman standing the requisite two metres ahead of her in line. After Nancy said “Good morning,” the woman had asked, “Are you American?” Without waiting for an answer, she added, “Are you glad to be here instead of there?” The woman then proceeded to say that she watched CNN “all the time,” and was “frankly, surprised that Trump hasn’t been shot by now.” Nancy was surprised that she had to stand in line for only fifteen minutes before being admitted to the store; Michael was only a few minutes behind her. The next time we went shopping, Pak ’n Save had begun allowing anyone over age 60 to go to the front of the line. (Hurrah for white hair!) Once inside, it was hard to remember to stay two metres away from everyone else, but Nancy thought the most difficult task was getting the plastic produce bags open without licking her fingers. After the first few frustrating visits, she hit on a brilliant solution: she began saving the damp paper towel after hand-washing on the way into the store and using it as a finger-moistener in the produce department.

Nancy’s makeshift mask

In the early weeks of the lockdown, it was uncommon to see anyone other than store employees wearing masks because masks were so hard to find, and with fabric stores closed, few people were equipped to make their own. By mid-April, as the Ministry of Health began recommending masks for everyone in enclosed public spaces, we began to see more makeshift face coverings: mostly scarves and bandanas. Michael began pulling his neck gaiter up over his nose. On the way into Pak ’n Save one day, while Nancy was trying to figure out how to arrange the drawstring on her hat to keep her scarf from falling down, she realized that she might just as easily use the hat itself to cover her nose and mouth. Yes, it looked silly, but it was convenient—and it elicited thumbs-ups from several amused shoppers. Whether either the neck gaiter or the hat were effective germ filters was another matter, but at least we could show that we were trying.

Pak ’n Save was not our only source of food during our weeks of confinement because friends, neighbors, and sometimes complete strangers kept giving us stuff to eat. Concerned that the full-time missionaries might not be getting fed if they could no longer be invited into their homes, Dinsdale Ward members brought us bread, cookies, pies, and bags of fruit. One of the ward’s several Brothers Smith gave us an entire bag of groceries, left over from a project he had participated in to help the families of those who had lost jobs due to the lockdown. A woman we didn’t recognize knocked on our door early one Sunday morning and handed us an aluminum pan filled with balls of fried bread. Barry and Eva shared a bowl of fresh figs someone had given them.

Field mushrooms . . .

. . . transformed into bruschetta

And after one of Barry’s neighbors showed him how to pick field mushrooms when they started springing up in Temple View’s damp hollows, Barry deposited a big bag of fungi on our doorstep every other morning for a couple of weeks. For a while we had mushrooms at almost every meal: in omelettes, on pizza, with pasta, over toast—so many mushrooms that it was kind of a relief when Barry announced one morning that there were no more to pick.

Free feijoas

Feijoa jam

And then there were the feijoas. Feijoas are to New Zealanders what zucchinis are to home gardeners in the U.S.—the thing that everybody grows because they’re easy and prolific, and because they’re so prolific, the thing that everybody is eager to give away. But feijoas are not vegetables; they are a type of fruit we had never seen or tasted before. They are about the same size and shape as kiwi fruit, but instead of being fuzzy and brown, they are smooth and green.

Feijoas ready for consumption

You eat a feijoa by cutting it in half and scooping out the soft green flesh with a spoon. The texture is similar to a kiwi, but very slightly gritty, like a pear, and the flavor is, well, indescribable. Sweetly tangy. Like nothing else. April through June is peak season for feijoas, so on our daily walks around Frankton and Dinsdale during the lockdown, we started noticing the tree-size feijoa bushes in nearly every yard. When feijoas are ripe, they fall by themselves, so you harvest them by picking them up off the ground. In some yards we passed, you would not have been able to walk from the driveway to the front porch without having to kick feijoas out of the way. In others, the trampoline (a feature of many yards here) was littered with so many feijoas that it looked like an IKEA ball pit with the red, yellow, and blue balls removed. Yards with few feijoas on the ground were likely to have a box or a bin of them next to the letterbox with a hand-printed sign that said: “FREE.” We rarely needed to help ourselves from these bins, however, because bags of feijoas kept mysteriously appearing on our doorstep.

Feijoas thus became the main ingredient of many culinary experiments. With nowhere else to go for a prepared meal, and few other places to turn for recreation and entertainment, everyone in the developed world seemed to end up in the kitchen, testing new recipes and trying new cooking techniques, and we were no exceptions. In addition to making feijoa cake, feijoa crumble, feijoa jam, and feijoa leather (all made even better with a hint of fresh ginger), Michael decided that this was the time to become a proficient bread-baker (as soon as we were able to replenish our flour supply).

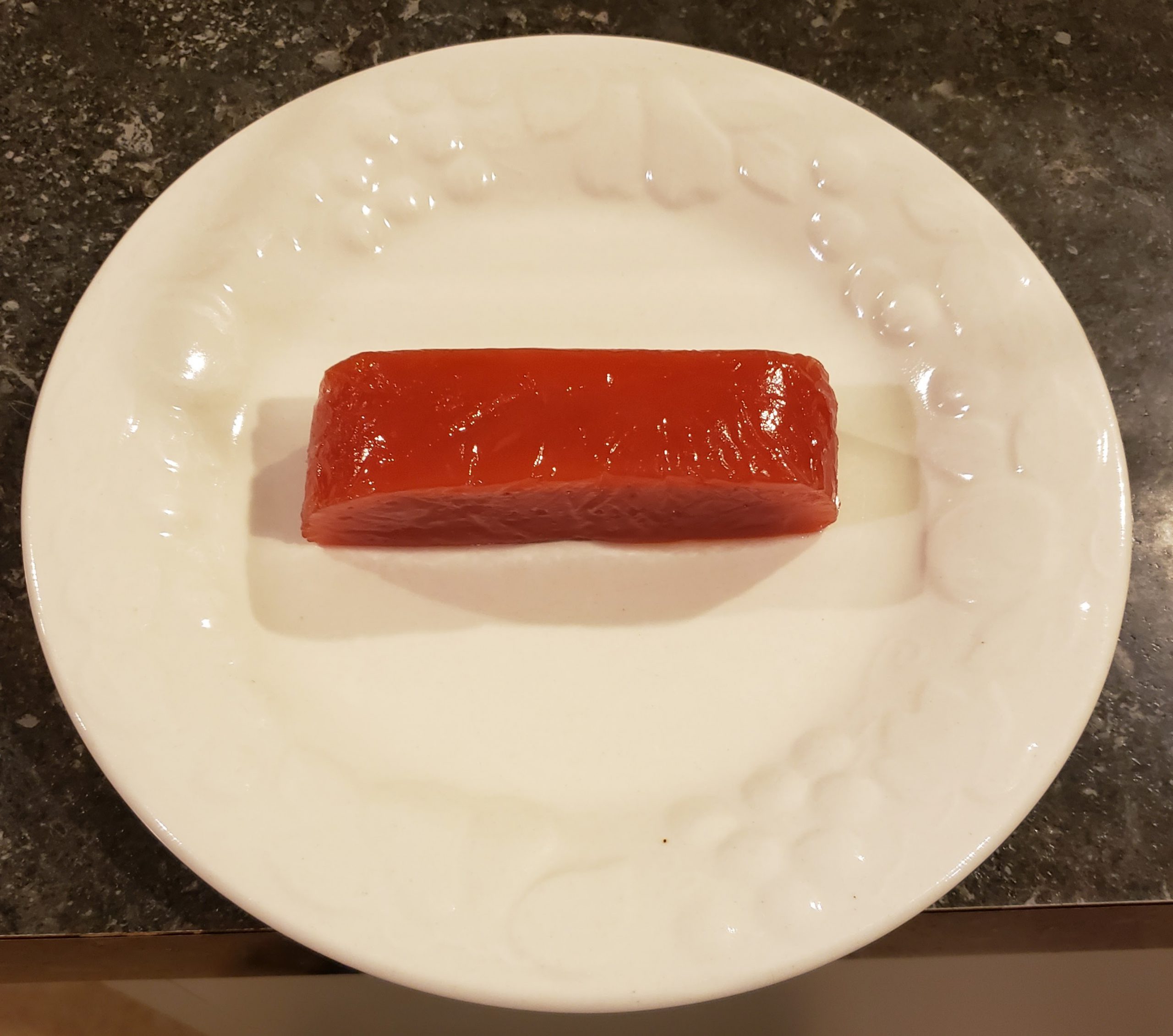

Quinces

A slice of membrillo (quince paste)

Nancy turned a couple of pale yellow, rock-hard quinces we bought at a farm stand into a bright magenta, delectable concoction called membrillo (or less poetically, “quince paste”) simply by cutting them up and cooking them with a little water and sugar. It was fun to exchange recipes and the results with other missionaries and Dinsdale Ward members.

As far as we knew, no one in Hamilton had contracted COVID-19, so the threat of becoming ill seemed distant. Nevertheless, flu season was beginning here in the Southern Hemisphere, and Sister D, the mission nurse, wanted to make sure we were prepared. Every missionary was instructed to get a flu shot even if we had already received the vaccine during the past six months.

Waiting in line to request a flu jab

Get your flu jab at the pharmacy

We were told to report for our “jabs” (standard NZ terminology for injections) at a Dinsdale pharmacy, where all we would need to do was show our missionary name tags, fill out a form, and roll up our sleeves. The pharmacy was within walking distance of our flat, but Michael was not about to let Nancy walk over, knowing that if she fainted, we might be there for a long time before she was able to walk home. (Nancy is prone to vasovagal syncope, so we always assume that she may faint when she gets a shot. If you’re a long-time follower of our blog, you may recall reading about her fainting episode when getting immunized for our trip to Kenya in 2018.) The other reason for taking the car to the pharmacy was that, due to COVID-19 restrictions, we would not actually be able to go into the building and thus would need to wait for service either on the sidewalk or in the car. The protocol for getting a flu jab involved ringing the bell at the pharmacy door, waiting for the pharmacist’s assistant to open it, and then explaining what you had come for. After the assistant returned with the proper forms, you went back to your car to fill them out, and then a few minutes later she would come out to your car and pick them up. Eventually the nurse practitioner or whoever was authorized to administer the jabs would come out and stick you as you sat in your car, just like that—no preparatory alcohol swab or anything. Nancy reclined her seat and then had to rearrange herself so the nurse practitioner could reach her upper left arm more easily through the car door. No fainting this time.

Elder Allen Dee Pace

Despite feeling perfectly healthy ourselves, it was impossible to forget that a dread disease was abroad in the world, and that no one was truly safe. We began tuning to Radio New Zealand’s nightly broadcasts, listening for the number of new and active COVID cases, and sobered whenever the announcer reported another death. One evening toward the end of April, we learned that the first Latter-day Saint missionary had succumbed to COVID-19, and were stunned to realize that it was someone we knew: Elder Allen Dee Pace. He and his wife had been part of our cohort at the Missionary Training Center in Provo, and although our contact with them was limited because we were in different districts, we had enjoyed talking with them between classes and over lunch, and had looked forward to staying in contact during our missions and beyond. Elder Pace was an unforgettable character: a former high school administrator and drama instructor who also was an active theatrical performer. Listening to him speak, we could vividly imagine how delightful it would have been to see him on stage in a role like Lord Fancourt Babberley in Charley’s Aunt—one of his favorites. Indeed, when we asked him which roles he had liked best, he told us that he loved the challenge of playing women. After we described Elder Pace to the other MCPCHC missionaries, one of them said, “He sounds like just the right person to reach out to all those people from New York City who have died of COVID-19 and have no idea what’s happened to them now that they’re on the other side of the veil.” It was such a lovely thought, Nancy decided to share it with Sister Pace when she sent condolences via email. She was surprised to find a response from Sister Pace in her inbox the next morning, thanking her for sharing an inspired idea. “It makes so many things make sense,” said Sister Pace. “It makes it bearable.”

So many missionaries were sent back to their home countries, the Hamilton Mission ended up with a surfeit of unused cars. They all got parked in the field outside the MCPCHC

The inconveniences of living under lockdown seemed so insignificant when compared to Sister Pace’s burden of grief. “We’re all in this together,” Jacinda Ardern had said, and indeed we were. We missionaries, along with all members of The Church of Jesus Christ, had made a covenant at baptism that we would “bear one another’s burdens, … mourn with those that mourn; yea, and comfort those that stand in need of comfort” (Mosiah 18:8-9). Unable even to offer a hug to anyone outside our own bubbles, we had to think more creatively about how to care for those who were hurting. Phone calls, Zoom meetings, taking a meal to someone with the sniffles who was afraid to leave her flat—we did what we could. We’re still doing what we can. Ultimately, though, the greatest help we can offer anyone is to bring them to Jesus Christ and assure them that through his atonement and love, sorrows and sicknesses as well as sins can be swept away. We are grateful to know that no matter how long the pandemic lasts, no matter how much suffering must be endured before it ends, God is mindful of us. And even when we mortals are required to keep our distance from one another, the Savior will always be there at our side.

Enjoy reading your posts .. such a blessing to have you both in our ward and to learn from your beautiful experiences and testimonies. God bless you Elder and Sister Harward.