Smith the Grocer

When we visited the Old Bank Arcade in Wellington’s central business district on Friday we noticed a bakery-café called Smith the Grocer that looked good, so we decided to go back on Monday morning for breakfast. Another reason to return to the Old Bank Arcade was to see the building’s animated musical clock in action. The clock is suspended from the ceiling of the former banking chamber; most of the time it looks like a gold and silver hot-air balloon, but every hour on the hour, the big silver sphere opens its petals like a blooming flower to reveal animated scenes from Wellington’s history. We timed our breakfast at Smith the Grocer to give those of our group who had missed the clock’s opening on Friday a second chance to watch.

People in Edwardian dress walk past the bank back in the days when the building was new |

A merchant watches his barrels rock on the pier during the 1855 earthquake |

British Redcoats raise the Union Jack over Lambton Harbour; the nearby Māori seem curiously unconcerned |

The statue of author Katherine Mansfield by Virginia King is about 3 metres tall

After breakfast (french toast with a broiled banana and a big pile of bacon for Michael; scrambled eggs on ciabatta with spinach, mushrooms, and avocado for Nancy) we went back to the Intercontinental Hotel to brush our teeth and check out. We stashed our luggage in the van and left it parked in the adjacent lot, where we figured it would be safe under the gaze of the hotel’s security guards, then walked about 15 minutes north toward Parliament for a scheduled tour.

On the way, we passed some interesting public artworks. One was Woman of Words, a modernist statue of modernist writer Katherine Mansfield (born in Wellington in 1888). Phrases from Mansfield’s personal journals and short stories (such as “Miss Brill” and “The Garden Party”) have been cut into the surface of the stainless-steel statue, and we’re told that they glow from within at night.

The three components of Kaiwhakatere (The Navigator) by Brett Graham represent an altar, a bird’s head, and a canoe

Another sculpture, called Kaiwhakatere (The Navigator) was near the parliamentary campus. Its three components, built of cobblestones, symbolize gratitude for the higher power that guides our journeys.

New Zealand’s Supreme Court building opened in 2010

“The Beehive,” parliament’s executive wing

Press Briefing Room

Banquet Hall in The Beehive

The campus of New Zealand’s national parliament comprises four separate buildings whose architectural styles are even more distinct than their purposes. The most unique one houses the executive wing and is known as “The Beehive” because it resembles a skep, a type of man-made beehive woven from straw. The nickname is also an apt metaphor for all the activity going on inside. Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern (definitely the queen bee) and cabinet ministers have their offices there.

In the news briefing room, we got to take turns standing behind the lectern where Jacinda regularly appears to give us updates on COVID-19 restrictions.

The Beehive also includes a large banquet hall used for state dinners and receptions. (Visitors are not allowed to take photos inside any parliament buildings; indeed, we had to leave all our digital devices at the security desk before the tour began, so the interior photos included here came mostly from www.parliament.nz.)

Parliament House, where the House of Representatives meets

A corridor connects The Beehive, which was completed in 1981, to Parliament House, which was built between 1914 and 1922 to replace an earlier building that burned down in 1907. Parliament House is decorated in a much more traditional style and contains the debating chamber, legislative council room, speaker’s office, committee rooms, and wide corridors filled with artwork and historical displays.

Parliament House Visitors Centre

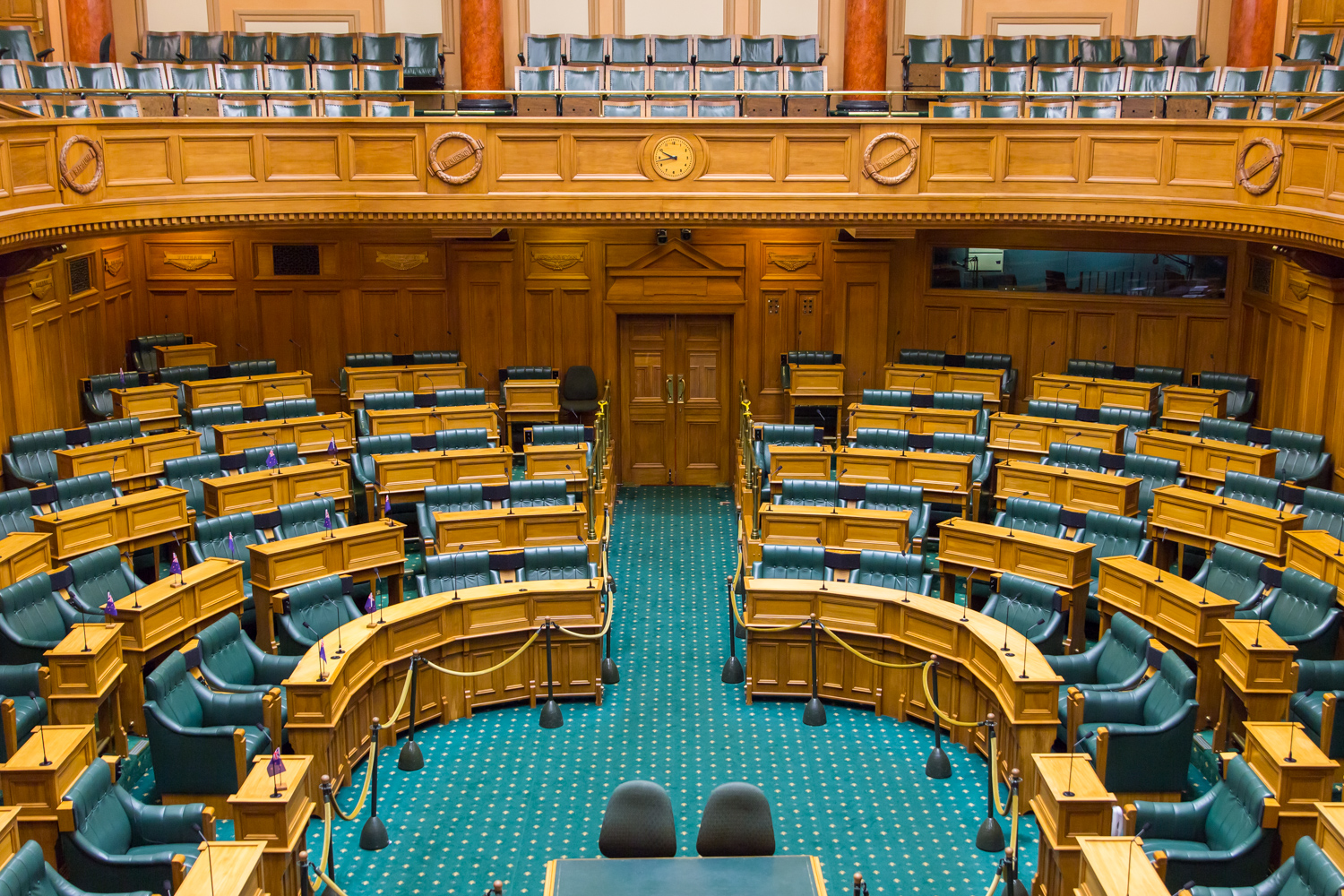

Parliament Debating Chamber

Originally, New Zealand’s parliament was set up like the British system, with two chambers. However, New Zealand’s unelected Legislative Council (analogous to the U.K.’s House of Lords) was abolished in 1951; the remaining chamber is called the House of Representatives. This is an election year, so we have been observing the campaign process and have had to learn how members of parliament are elected and seated. It’s quite different from the way congressional representatives are elected in the U.S.

Legislative Council Chamber

Māori Affairs Select Committee Room

New Zealand citizens and permanent residents over age 18 who have lived in the country for at least 12 consecutive months may enroll to vote, and each enrolled voter gets two votes in a general election. These votes affect the composition of parliament in different ways. The first vote is for a named individual associated with a party who lives in and is seeking to represent one of the country’s 72 districts. The person who gets the most votes in a given district wins the election for that district, just as in the U.S. Congress. But a New Zealander’s second vote is for a party. Party votes are tabulated at the national level, and each party gets a corresponding percentage of the parliament’s 120 seats. The seats allocated to a party are then filled by the MPs from that party who won their district elections. In the event that a party does not win enough district elections to fill the seats allocated to it based on percentage, then that party’s remaining seats are filled from within the party ranks. In the opposite case, if districts have elected more MPs from one party than that party has been allocated seats, then the total number of seats in the House is increased so that each MP who won a district election can be seated as a member. One of the benefits of New Zealand’s mixed-member proportional system, which was established in 1993, is that its parliament has become more pluralistic. The prior system favored the two dominant parties, Labour and National, in the same way that the Democratic and Republican parties dominate U.S. elections, but now there are several parties with significant representation in New Zealand’s governing body.

The prime minister is appointed to that office by the governor-general (acting on behalf of and as a surrogate for the Queen of England), chosen from among the members of parliament elected to represent their various districts. By convention, the governor-general appoints someone who already has the support and confidence of a majority of the MPs. Once sworn in by the governor-general, the prime minister remains in the post until dismissal, resignation, or death in office. She or he, like all ministers, holds office “during the pleasure of the governor-general” so, theoretically, the governor-general can dismiss a prime minister at any time; however, convention heavily circumscribes the power to do so. The governor-general may dismiss a prime minister under certain circumstances, such as when a no-confidence motion is made in the House of Representatives against the government. If a prime minister—and, by extension, the government—loses a confidence vote in the House, or the party she or he represents does poorly in a general election, convention dictates that the prime minister should resign. (Neither Jacinda Ardern nor the Labour Party seems in danger of being ousted from power in this month’s election.)

Parliamentary Library

Foyer of the Parliamentary Library

Parliamentary Library Reading Room

The third building we toured was the Parliamentary Library. When the national capital of New Zealand was moved from Auckland to Wellington in 1862, many of the books, reference materials, and accounting records from the parliament’s original library were lost in a shipwreck. What was left became the foundation of a new library, first housed in six large rooms behind the provincial council building where the parliament convened until the first Parliament House was built in the 1880s. By 1897 the library’s holdings had increased to 40,000 volumes—more than could be accommodated in six rooms—so in 1899, the library moved to its current structure, an addition to Parliament House. Thanks to its masonry construction and the iron fire door separating it from the rest of the building, the library survived the fire that destroyed the original Parliament House in 1907. The oldest surviving building on the parliamentary campus, the library holds over 600,000 items for use by the representatives and their staff.

Bowen House, behind a World War I Memorial

The fourth building on the parliamentary campus is Bowen House. It’s a modern office high-rise across the street from the other buildings, connected by an underground tunnel. It was not included on our tour, presumably because it looks a lot like any other office building.

The Wellington Cathedral of St. Paul

After the tour of parliament, we walked two blocks north to the art deco-style Wellington Cathedral of St. Paul. Designed shortly after the 1931 earthquake that destroyed the cathedral in Napier, this Anglican church was built of reinforced concrete so it wouldn’t suffer the same fate.

National Library

Original Waitangi Treaty

From there we went across the street to the National Library so we could see the original Waitangi Treaty. Its dramatic viewing room is impressive, but being museum people we spent as much time examining the “smartglass” display cases as we did the fragments of the historic document inside. (For background on the Waitangi Treaty, see our earlier post about visiting the Waitangi Museum and Treaty Grounds in June.)

Old St. Paul’s Church

Interior of Old St. Paul’s Church

This stained-glass window from Old St. Paul’s appeared on a New Zealand postage stamp at Christmastime several years ag

Our last stop in the neighborhood was at Old St. Paul’s Church, which had served as Wellington’s cathedral for nearly a century until the new cathedral opened in 1964. Old St. Paul’s is a lovely gothic-style chapel constructed from native timber, with splendid stained-glass windows. While no longer used for regular parish worship, it is a popular venue for weddings, funerals, and other services.

We had planned to return to the wharf for lunch, but by this time we were hungry and decided to try to find something in the neighborhood. We rejected Kapai on our first pass because the storefront deli didn’t have enough seating for our group, but when we couldn’t find any other eateries in the vicinity, we went back. Everyone seemed satisfied with their choice of wraps, salads, soups, and smoothies even though we had to take turns sharing stools at the narrow counter.

National rugby team bus

As we walked back toward the Intercontinental Hotel to pick up the van, we could see a bus parked in front that was emblazoned with the emblem of the All Blacks, New Zealand’s national rugby team. Dozens of matching black roller bags also sporting All Blacks insignia were lined up across one side of the lobby. We weren’t sure whether the team had just arrived or if we had been sharing the hotel with the players last night without knowing it. If the latter, they had not made their presence known—for which we suppose we should be grateful.

Exotic succulent at the Wellington Botanic Garden

View of Wellington from the cable car

Eva, Wendy, and Diane inside the cable car

The Cable Car Museum doubled as a polling place this week

During the last few hours before our flight back to Hamilton, we drove to the Wellington Botanic Garden and enjoyed strolling around the displays of both native and exotic plants. Sadly, the roses were not yet in bloom, but the views of the city and harbor from the garden’s hilltop location were spectacular. We also rode the cable car from the top down to Lambton Quay and back just for the fun of it.

With some extra time before we needed to arrive at the airport, we decided to drive an indirect route, cutting through the middle of the Miramar Peninsula to Seatoun, and from there along the scenic Great Harbour Way to Point Dorset. A fort had been established on this headland in the mid-1800s for strategic defense; it also was used for military training between the World Wars. Fort Dorset was decommissioned in 1957 and later dismantled, although some vestiges of gun emplacements and observation posts remain. The main thing we observed besides the natural beauty of Breaker Bay was a group of scuba divers—undoubtedly true Kiwis because they seemed completely unfazed by the water’s frigid temperature.

Scuba divers at Breaker Bay

A life-size figure of Gandalf on a giant eagle is one of Wētā Workshop’s special creations for the Wellington Airport

We reached the airport by continuing along Great Harbour Way around the south end of the peninsula. Alan and Wendy deposited the rest of us at the terminal and then went to pick up Wendy’s brother, who then dropped them at the airport before returning the van we had borrowed to the Wellington Mission office. We browsed through the airport shops as we waited to board the plane, and although it was getting close to dinnertime we decided to just get smoothies because we’d already eaten two big meals that day.

From a small plane flying at a relatively low altitude on a clear evening, we were able to get a spectacular bird’s-eye view of the west side of the North Island as we flew north to Hamilton.

Arial photograph of Mt. Taranaki (we cannot take credit for this photo)

Snow-capped Mount Taranaki, an almost perfectly conical volcano situated in the center of an almost perfectly round national park, is a uniquely impressive sight from the air. The stark contrasts between the white peak, the dark-green bush reserve, and the more golden dairy farmland around the park were absolutely stunning. And while not as unusual a view, the crazy-quilt pattern created by the Waikato’s farms and cow paddocks was rendered more dramatic by the long shadows cast by windbreaks across each quilt patch as we approached the Hamilton Airport just before sunset. Back at home in our missionary flat, we unpacked our bags and prepared to go back to work at the Pacific Church History Centre the next morning.

Once again, a fun and informative jaunt for us to enjoy vicariously, including the meals! Thanks for the photos.

Great Pictures. Thank you.

When will you be headed back to the states?