We are not sure when this tradition started, but during the two weekends a year when a general conference of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints is held, regular Sunday worship services are suspended, and all Church facilities that normally are open on Saturdays (such as temples, distribution centers, and museums) close down. The practice of closing on Saturday made sense for those living in or near Salt Lake City in the days before COVID, because many of the people who work in Church facilities were expected to attend at least one if not all of the conference sessions. Even now, it may still make sense for most Church members who are expected to participate in the proceedings via a live broadcast or satellite transmission. But it makes no sense for Church members who live in New Zealand, where watching the Saturday morning opening session of general conference live means tuning in at 4:00 on Sunday morning. Notwithstanding that the timing of general conference has no impact whatsoever on the Saturday schedule of New Zealand’s Latter-day Saints, the manager of Hamilton’s Church Distribution Centre was instructed to close the store on Saturday 3 October 2020, and the Matthew Cowley Pacific Church History Centre, with whom the store shares a building, was instructed to close as well.

We are not sure when this tradition started, but during the two weekends a year when a general conference of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints is held, regular Sunday worship services are suspended, and all Church facilities that normally are open on Saturdays (such as temples, distribution centers, and museums) close down. The practice of closing on Saturday made sense for those living in or near Salt Lake City in the days before COVID, because many of the people who work in Church facilities were expected to attend at least one if not all of the conference sessions. Even now, it may still make sense for most Church members who are expected to participate in the proceedings via a live broadcast or satellite transmission. But it makes no sense for Church members who live in New Zealand, where watching the Saturday morning opening session of general conference live means tuning in at 4:00 on Sunday morning. Notwithstanding that the timing of general conference has no impact whatsoever on the Saturday schedule of New Zealand’s Latter-day Saints, the manager of Hamilton’s Church Distribution Centre was instructed to close the store on Saturday 3 October 2020, and the Matthew Cowley Pacific Church History Centre, with whom the store shares a building, was instructed to close as well.

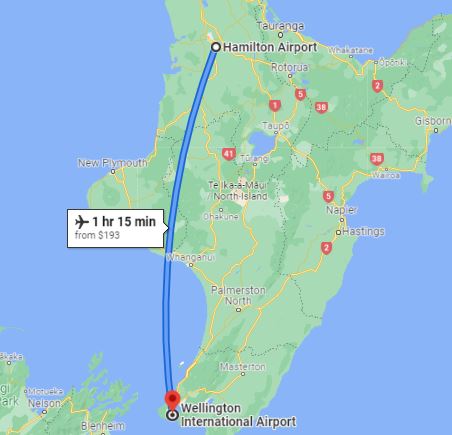

Rather than complain about the illogic of the situation, the full-time staff of the MCPCHC decided to take advantage of a long, free weekend and plan an out-of-town trip. So when our alarm went off at 5:00 that Saturday morning, it was not waking us for general conference (recordings of which we could watch online later in the week), but for our flight to Wellington.

The cheap fares we got from Air New Zealand’s “grab-a-fare” discount program did not allow us to check any luggage, so we packed very lightly. Once at the airport, however, we discovered that we needn’t have been so careful. No one weighed or measured our carry-ons, and we noticed that other passengers were lugging bags obviously exceeding the size and weight limits specified on the ANZ website.

Hamilton Airport

Air New Zealand short-haul Bombardier Q300

This was our first experience at the Hamilton Airport. It’s much like Southern California’s Orange County Airport was back in the 1970s (before it was renamed for John Wayne): one terminal and two runways, with an apron that accommodates only five average-size planes. Hamilton Airport has a café, but it had not yet opened when we arrived for our flight, so because we had forgotten to bring the yogurt and cereal we had planned to eat for breakfast, Michael had to be content with a day-old muffin from the coffee counter and Nancy with hot chocolate, plus a bag of nuts and dried fruit she had stuck in her purse for just such an occasion.

Gandalf provides the only security check at Hamilton Airport

One thing about the Hamilton Airport took us by surprise: the complete lack of security. Not only did no one ever weigh our bags, but there was no x-ray machine to put them through, no sniffing dogs, no metal detectors, no body scanners, nothing. No one even asked to see our ID. We never heard a boarding announcement, but when everyone else in the terminal started heading toward the gate, we figured it must be time and joined the queue. At this point, everyone donned face masks, which were required aboard the plane even though all 40 of New Zealand’s active COVID cases were in managed isolation quarantine. (Later, we learned that Donald Trump was among the 53,580 new cases reported in the U.S. that day.) After scanning our own boarding passes, we made our way to the last row of seats on the plane. Given that there were less than 70 other passengers and we’d be in the air only 75 minutes, we didn’t mind sitting in the back.

One of our volunteer museum guides had grown up in Wellington and had told us what to expect as we were flying in: “It will be really bumpy as you’re coming in to land, and when you look out the window and see nothing but water, you’ll think you’re going to die. But don’t worry—you won’t. The pilots do this all the time,” she explained. Her description was not very comforting but it allowed us to go into the situation better prepared. We did indeed experience turbulence as the plane descended, and it was rather disconcerting to look out the window and see nothing but water—but neither of us was overly concerned about dying.

The Wellington Airport runway is built on reclaimed land

Wendy and Alan (aka Elder and Sister T) had gone down to Wellington a couple of days earlier so they could record some oral history interviews and have a little extra time to visit with friends and family. The Ts had served previously as self-reliance specialists for the Wellington Mission, and Wendy’s brother George and his wife Terry are currently serving there as member-leader support missionaries. Because they had connections, Elder and Sister T had arranged to borrow a van from the Wellington Mission’s fleet for us to use over the weekend. They were there with the van to pick us up when we, Diane, Eva, and Barry got off the plane about 8:30 a.m..

At the windswept top of Mount Victoria

Because he was familiar with the city, Alan offered to be our chauffeur through the weekend—for which we were grateful because we quickly discovered that driving through Wellington is a lot like driving through San Francisco: one must navigate many curvy roads that either skirt the ever-present shoreline or climb steeply over the hills—or both—while also paying close attention to heavy traffic, avoiding pedestrians, and determining when it may be safe to enter a roundabout. Passing through the Mount Victoria Tunnel, Alan honked the horn in compliance with a local tradition, meant either to honor or ward off the ghost of a teenage girl who was murdered there just before the tunnel opened in 1931. His toots were matched by those of many other drivers, each reverberating repeatedly through the 623-metre passage.

Northwest view of the city

Our first destination was the lookout atop Mount Victoria, which, on a clear day like this one, provides a stunning view of the city to the west, the airport to the south, and the water all around. Like San Francisco, Wellington is situated on a peninsula that forms a well-sheltered bay, away from the open waters of the Pacific. The back side of the mountainous peninsula is on the Tasman Sea, and Cook Strait, where the two oceans meet west of Wellington, is one of the world’s most treacherous passages for seafarers to navigate.

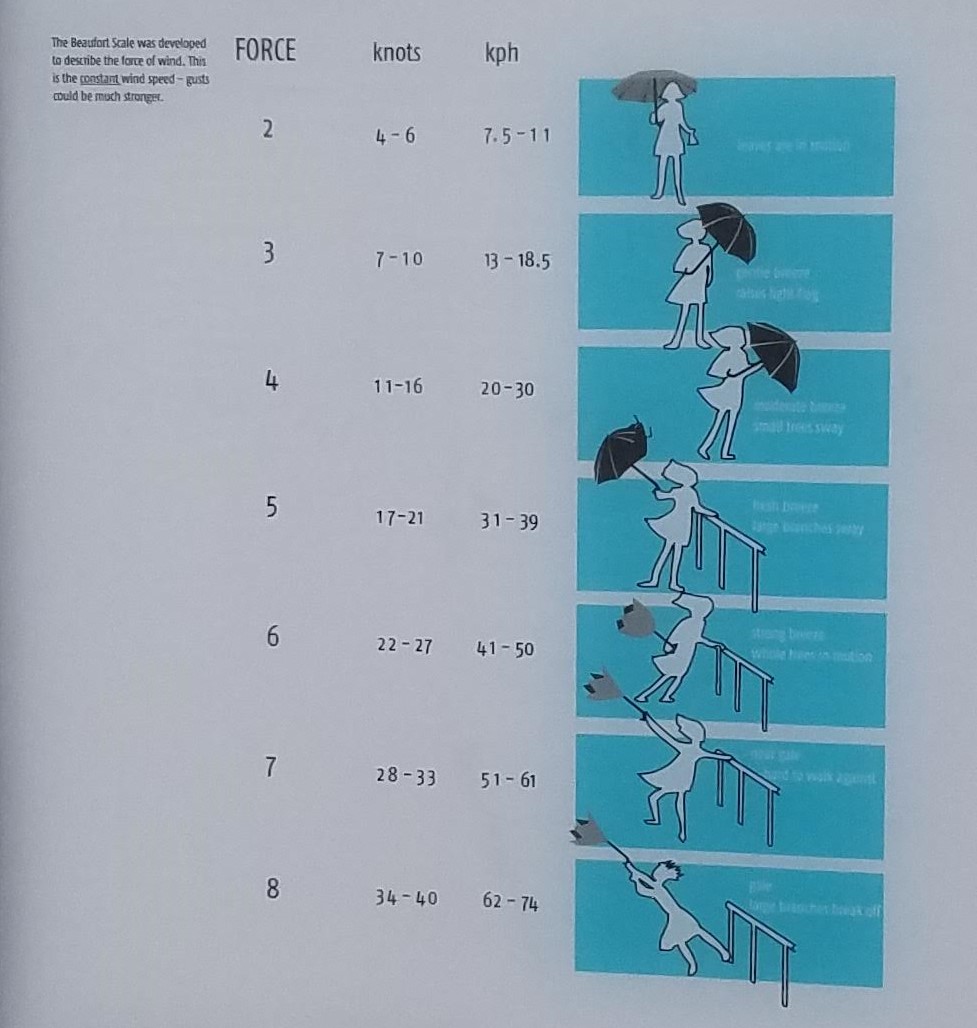

Description of wind forces

One of the reasons for Cook Strait’s dangerous reputation is the wind. Wellington is certifiably the windiest major city in the world, with an average constant wind speed (not including gusts) of over 15mph (24kph). On 173 days of the year, wind velocity averages more than 37mph (60kph). And we were there in October, certifiably Wellington’s windiest month. We could definitely feel those powerful air currents on the top of Mount Victoria, where we had to shout to make ourselves heard above the roar. An information board uses diagrams to cleverly explain the effects of Wellington’s unique weather patterns on people like us. As the sign suggested, we were “blown away” by the experience.

St. Gerard’s Catholic Church and Monastery at the foot of Mount Victoria. On the day we drove past, the door was open–just as it had been for Barry’s father

As we were driving down the hill from the lookout, Barry pointed out a church situated at the bottom of the steep incline just at the point where the road makes a sharp turn to the left. “See that church?” he said. “It’s a monastery. When my father was a boy, he lived up the hill from here, and one day he decided to get in his wagon at the top of the street and ride it all the way to the bottom. Well, he couldn’t make the sharp turn in his wagon, and he couldn’t stop, so he ended up sailing right through the open door of that monastery. He didn’t get hurt, but he really shook up the brothers inside!”

“Eat, drink, and be Welly”: banners touting the food festival that got cancelled flapped in the wind along the quay

The Intercontinental Hotel

Our next stop was in central Wellington, where the wind was constant but not nearly as strong as it had been at the lookout. Alan parked the van near the quay and we spent an hour or two strolling along the waterfront, peering into the few shops that were open. COVID concerns had caused an outdoor food festival scheduled for that weekend to be cancelled—a pity, because the weather was gorgeous, and no doubt the event would have been a lot of fun. On the other hand, with no food festival, we didn’t have to contend with any unusual crowds.

Star Boating Club

Lambton Harbour in Wellington Central is reserved for recreation rather than commerce, and is a popular venue for rowing clubs to practice and compete.

Monument to Aotearoa New Zealand’s legendary first settlers

The waterfront also features a monument celebrating the arrival of Kupe Raiatea, his wife Hine Te Aparangi, and Pekahourangi, the tohunga (holy man) who accompanied them, in their waka (canoe) Matahourua. According to Māori legend, they were the first humans to reach the shores of Aotearoa.

Inside the Old Bank Arcade

TORY & KO.’s Stella collection

We also walked a few blocks inland to the Old Bank Arcade, a retail and office complex that consists of four buildings from the late 1800s, the most prominent of which is the wedge-shaped Bank of New Zealand. Today the four are connected by an inner court filled with shops and cafés. One of the shops in the arcade is a bespoke jewelry boutique Nancy had just read about in Air New Zealand’s in-flight magazine. One of TORY & KO.’s claims-to-fame is that Kate, the Duchess of Cambridge, chose some of their creations to wear when she toured New Zealand in 2014. During our visit, the shop was featuring a line called “Stella,” but because the only jewelry our Stella ever wears is her wedding ring, we didn’t even consider buying her a pricey necklace.

Remains of the Inconstant

Underneath one end of the Old Bank Arcade are the remains of the Inconstant, a ship that had foundered on the rocks outside Wellington Harbour around 1850. The wreck was towed to the quay in town, permanently anchored, and turned into a warehouse that came to be known as “Plimmer’s Ark.” The answer to the question of how the ship ended up about 300 metres from the waterfront is an interesting one. In 1855, an earthquake measuring 8.2 raised the shore of the harbor, leaving Plimmer’s Ark high and dry. Over the next thirty years, the area of the former quay was filled in and the upper timbers of the landlocked ship were demolished so another building could be erected on the spot. During the construction of the arcade in the 1990s, the old ship’s hull was exposed and efforts were made to preserve and display it as a piece of Wellington’s history.

Our group met back at the van about 11:30 a.m. so that Alan could transport us to Miramar, a community on a smaller peninsula east of town that has been nicknamed “Wellywood” because it is home to so many establishments associated with the film industry. The best-known of these is Wētā Workshop, where the fantastic props and costumes for Lord of the Rings, The Chronicles of Narnia, and many other films were created. The workshop is named for a group of insect species that are unique to New Zealand and look something like crickets with spiny legs. Some wētā species are very large—like, big enough to fill your outstretched palm. We have not encountered any really big ones because they live only on certain offshore islands, but smaller varieties are fairly common. We suppose the founders of Wētā Workshop chose the name because it, too, is unique to New Zealand, and maybe because the wētā looks like the kind of weird fantasy creature its designers might have dreamed up. By the way, it’s important to include the macrons when writing wētā (and to elongate the vowels when pronouncing it) because the te reo Māori word weta with no macrons means “excrement”—basically the same as (*ahem*) one of our common English four-letter words. (Since learning about this embarrassing faux pas, Wētā Workshop has taken great pains to add macrons wherever its name appears.)

The Larder

Entrance to Wētā Cave

A 9-foot troll may intimidate some visitors, but apparently not all. A nearby sign requests: “Please do not climb on the trolls”

How human feet are transformed into hobbit feet

Alan, Wendy, Barry, and Eva had taken the Wētā Workshop tour on previous visits to Wellington, so Michael, Nancy, and Diane just got dropped off and the others headed somewhere else. But before our workshop tour began, we had to have lunch. The three of us left in Miramar went to The Larder, which serves dishes composed of locally sourced food in an old house up the street from Wētā. Michael enjoyed the lamb rack with Israeli couscous, braised eggplant and harissa (a sauce made from hot chili peppers, paprika, and olive oil). Nancy loved her feta and goat cheese soufflé, which she described as like a high-class version of Puffy Cheese Bake (a favorite dish that our kids never learned to appreciate).

We had about a half an hour to browse Wētā Cave before our workshop tour began. The “Cave” is primarily a gift shop, but Michael found it more interesting than most gift shops because it includes several large display cases devoted to original costumes and props from movies we had seen. It was fascinating to see up close how detailed they were—and also to see how much some people are apparently willing to pay for a limited-edition polystone-and-resin statuette of the Balrog, complete with an LED-illuminated Flame of Udûn.

Should the residents of Miramar ever come under enemy attack, local militiamen could arm themselves in style at Wētā Cave

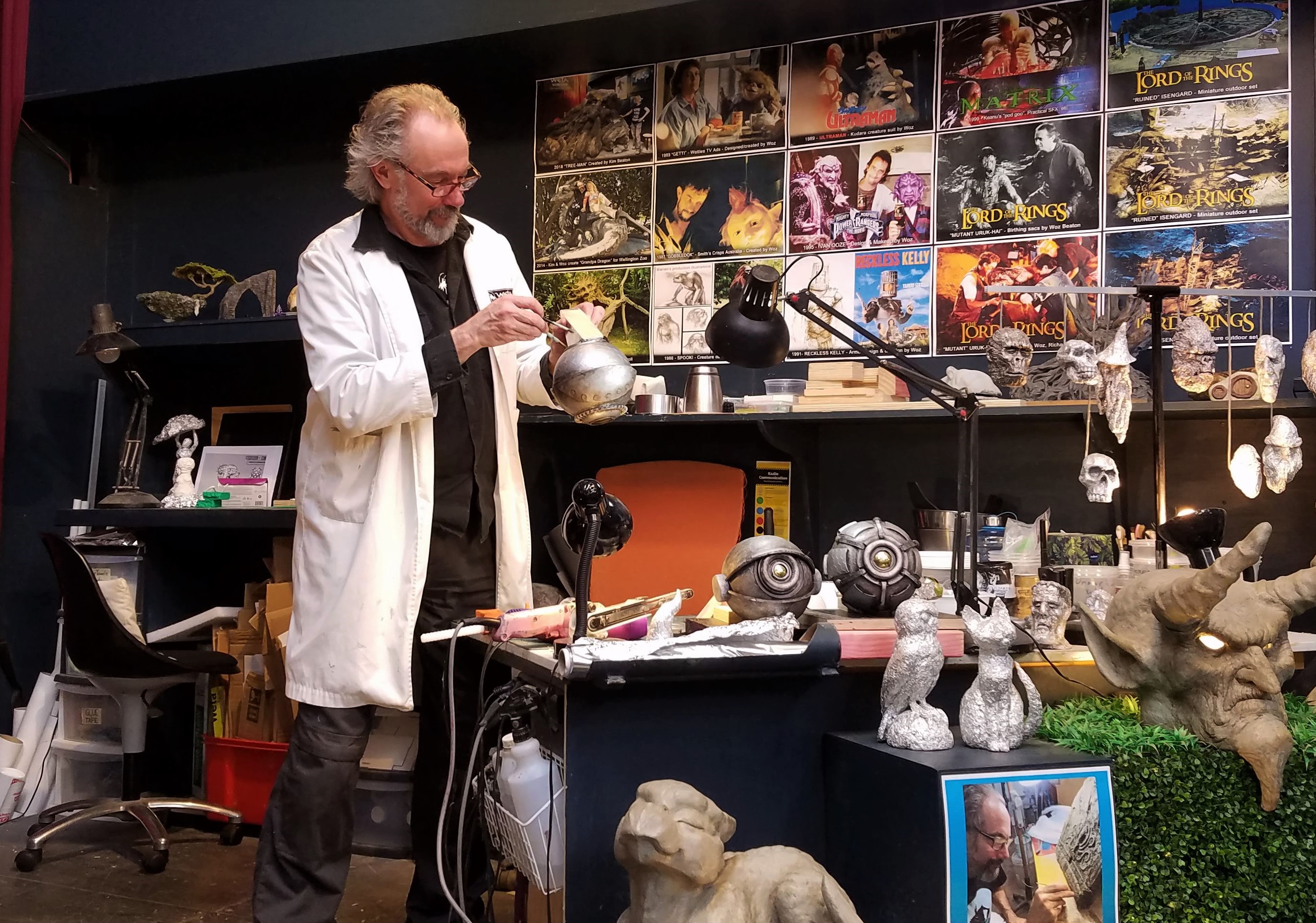

Warren paints a security camera cover

The workshop tour was even more fascinating than the Cave’s displays. Our guide, Matt, was from South Africa, drawn to New Zealand by the chance to maybe rub shoulders with Peter Jackson. Matt currently works in Wētā’s paint studio, but his goal is to direct and produce his own films someday. We think he ought to just keep giving tours, because he was both informative and engaging. Besides hobbit feet, orc masks, and elven armor, we saw several miniature settings for Thunderbirds Are Go, The WotWots, and other TV shows we’d never heard of before. We wish we could show you more pictures, but photography is not allowed in most areas of the workshop due to licensing agreements with Wētā’s clients.

Roxy Cinema

Ceiling of the Roxy Cinema gallery

We could, however, take photos while a prop artist named Warren painted a spherical Star Wars-esque gadget that turned out to be a cover for a security camera. (He was making a set of these so the security cameras in a new facility wouldn’t be so obvious.) Warren uses mostly found objects for his creations: things like milk bottle caps, pop-top can rings, razor-blade packages, and crushed aluminium foil. (Note that we spelled aluminium in the proper New Zealand way.) The camera covers were made from disposable plastic bowls that looked like Cool Whip containers—but weren’t, because the very idea of non-dairy whipped topping is anathema to New Zealanders.

A display case in the Roxy Cinema contains the Oscar won by LOTR’s film editor, who is a co-owner of the theatre

On our way out of Miramar after Alan and the rest of our cohort arrived to pick us up about 3:30, we stopped at the Roxy Cinema. Known as the Capitol Theatre when it opened in 1928, the art deco building eventually became a victim of the multiplex era and for a while was turned into a shopping mall—until shopping malls, too, went out of vogue. Reclaimed as a movie theatre in 2011, the updated Roxy is now a venue worthy of the creative masterpieces coming out of New Zealand’s film industry.

Little Penang

By the time we returned to Wellington Central, it was late enough in the afternoon to check into our rooms at the high-rise Intercontinental Hotel. We took a short rest before heading to dinner at Little Penang, a Malaysian restaurant where Nancy and Michael shared a “warm salad” of greens topped with a spicy peanut sauce and little chunks of crispy vegetable fritters, as well as a chicken curry that came with a side salad of julienned pineapple, cucumber, and apple. We thought the restaurant was deserving of the appellation given by at least one reviewer: the “top dive” in Wellington.

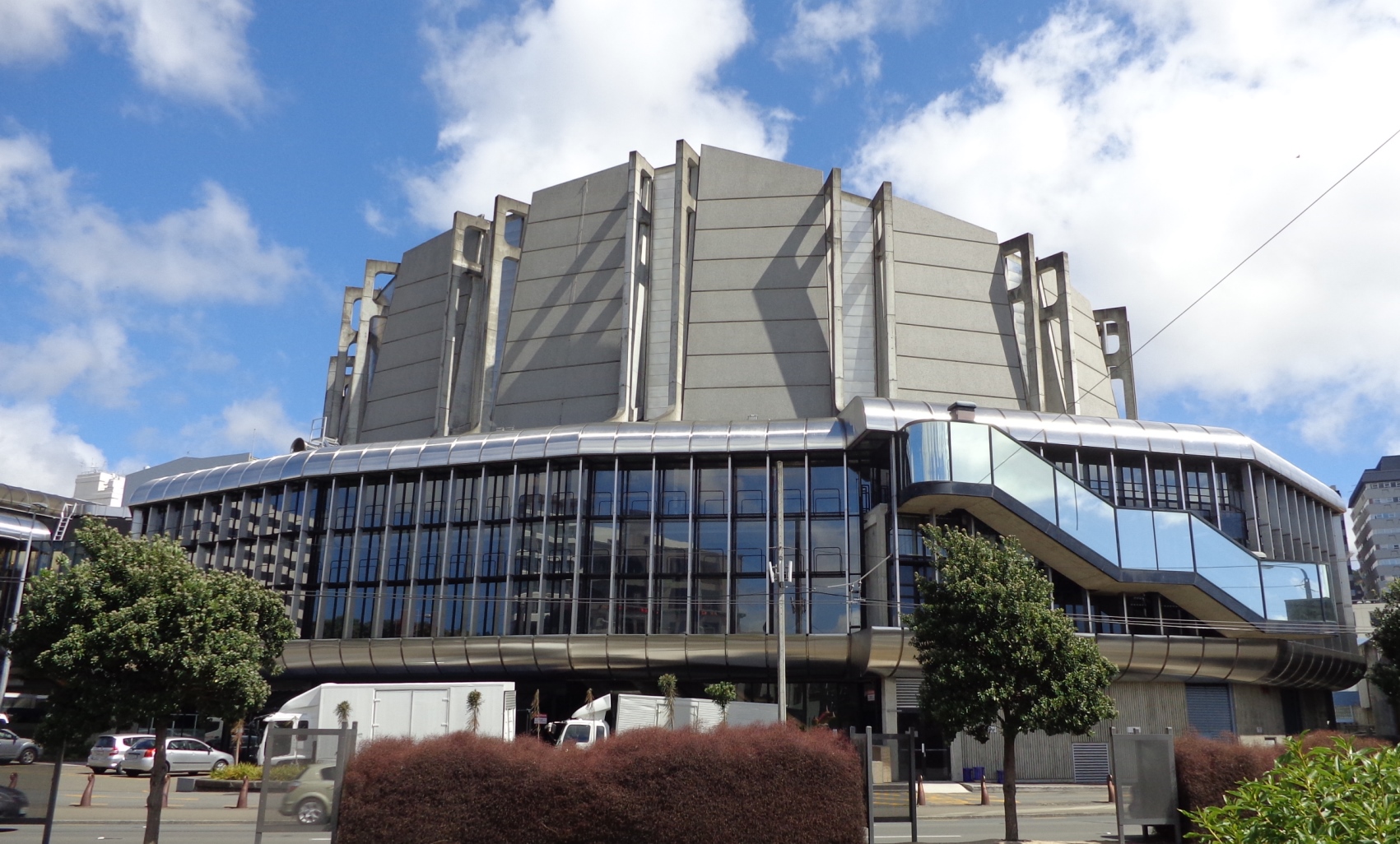

Michael Fowler Centre

Orchestra Wellington and the Orpheus Choir

After dinner, we made our way to Michael Fowler Centre, Wellington’s major arts and events complex. Built on reclaimed land near the waterfront next to Civic Square, the magnificent modern building opened in 1983 and is named for a former Wellington mayor who actively promoted the construction of a new venue for the performing arts. The Fowler Centre is home to the New Zealand Symphony Orchestra, the country’s premier orchestra. However, the NZSO was not on the program we had come to hear. We had tickets for a concert by the city’s other professional orchestra, Orchestra Wellington, and a non-professional choral group called Orpheus Choir Wellington that’s probably equivalent to Cincinnati’s May Festival Chorus. Two pieces were on the program: an infrequently performed choral symphony by Sergei Rachmaninoff called The Bells (inspired by a Russian translation of the poem by Edgar Allan Poe) and the beloved Requiem by Gabriel Fauré. The latter was the drawing card for us because we have sung it a few times; we were unfamiliar with the Rachmaninoff, but it sounded intriguing. Eva is a choral singer, too (like Nancy, a former member of the Brigham Young University A Cappella Choir), so it wasn’t hard to convince her and Barry to join us at the concert, and Diane came along as well because Diane is always game for new experiences.

This was to be Orchestra Wellington’s first live concert after the COVID lockdown forced the cancellation of the remainder of their 2019-2020 season, so the hall was full and spirits were high. By the interval, we understood why The Bells is rarely performed: it’s a heavy, turgid work that lacks the compelling forward movement of Poe’s poem (no doubt the fault of the “free” Russian translation), and quite frankly, we didn’t think the music was nearly as beautiful as that of Rachmaninoff’s better-known works. The orchestra was quite good, however, and the chorus was decent. Of the three soloists, the baritone and tenor were fine, but the soprano was disappointing. We guessed that she had once been a respected vocal coach and was now one of the Orpheus Choir’s preeminent fundraisers—either that, or she was the conductor’s wife, because her voice was clearly past its prime and not up to the demands of either piece. It was particularly painful for us to hear her wander off-key during the Requiem’s sublime “Pie Jesu,” but the Wellington audience offered loud, heartfelt applause to what must have been a beloved local musician. Indeed, the enthusiasm of the crowd for the whole event was infectious, and made us glad that we had come despite the concert’s deficiencies. And getting a look at the inside of the Fowler Centre’s impressive auditorium wasn’t bad, either.

Leave A Comment