Rain began pounding against our windows at the Busby Manor Resort in Paihia after we went to bed on Saturday night (30 May) and didn’t let up until Monday. Although we had come to the Bay of Islands prepared for such weather, none of us was interested in taking a walk along the beach Sunday morning. The clouds were so low and the rain so intense that we could not even see the beach from the windows that had provided such a great view the day before. Fortunately, we had already planned to hold our own “at- home” worship service, watching that week’s devotional from the Missionary Training Center in Provo, Utah. The MTC was operating mostly on a virtual basis at the time, so the talks were presented in a nearly empty auditorium.

Sister Naomi Toma Tai and Elder Benjamin M. Z. Tai

The speakers were Elder Benjamin M.Z. Tai, who had been sustained as a new general authority at our last general conference, and his wife Naomi. Sister Tai’s message was to “look up and beyond” so that we can see, like Elisha, that “they that be with us are more than they that be with them” (see 2 Kings 6:15-17). Elder Tai, who grew up in Hong Kong, explained that in Chinese, the character for crisis is composed of the two characters for danger and opportunity. He illustrated how a crisis can create opportunities for creative responses by sharing a personal experience. As a young man, Elder Tai did not know how to swim, so when he was playfully pushed into the deep end of a pool at a party, he faced a crisis. At first he floundered, too fearful to think clearly. But as he sank deeper under the water, he opened his eyes and noticed that someone else in the pool was propelling himself toward the surface by rhythmically moving his arms and legs. Young Benjamin saved himself from drowning by imitating the swimmer’s movements. Similarly, he went on, when we find ourselves in crisis situations, we need not fear. We can open our eyes and follow the example of those with more experience. We can study how others overcome fear with faith. We can follow the example of the Savior, whose power can save us from any crisis.

The sign posted at a Māori recreation area during COVID-19 restrictions advised: “Stay home. Stay alive”

When the devotional was over, we took the opportunity to see more of what the Bay of Islands had to offer, despite the driving rain. We had been told that the Whare Waka Cafe at the Waitangi Museum and Treaty Grounds was a good place to have lunch, so that became our first destination. A lot of other people must have heard the same thing about the cafe because it was crowded when we arrived. We couldn’t find an unoccupied table inside, but we did manage to snag one under a heater on the covered porch. We kept our raincoats on not only to stay warm, but to ward off drips from the leaky roof; the servers supplied us with extra napkins to mop up puddles that formed on the table. Fortunately, the food was as good as advertised: soups, sandwiches, and “cabinet salads” made with fresh, local ingredients like kumara and watercress. Even better was the dessert bar, from which Michael chose a delicious ginger tart.

Waitangi Museum

When we finished our lunch, Diane, Nancy, and Michael headed for the museum while Eva and Barry made a dash back to their car. They had decided not to pay $50 each to tour the museum again, having visited already within the past year, but they assured us that the experience would be worth the price.

Waitangi, as we’ve mentioned before, is the place where New Zealand began to exist as a unified nation with the signing of the 1840 treaty between the chiefs of many Māori iwi and hapu (tribes and subtribes) and representatives of the British Crown. The beautifully designed museum tells the complicated story of that treaty with thoughtful candor.

One of the first panels of the exhibit explains that:

All who come to this country have to cross a vast stretch of water to get here.

Boldness and great navigational skill brought Māori to these shores, then Europeans, hundreds of years later. Now two peoples had to navigate the unknown waters of a relationship.

Each had to come to terms with the other to get what they wanted. They tested boundaries, they negotiated, sometimes they clashed. The conversation began.

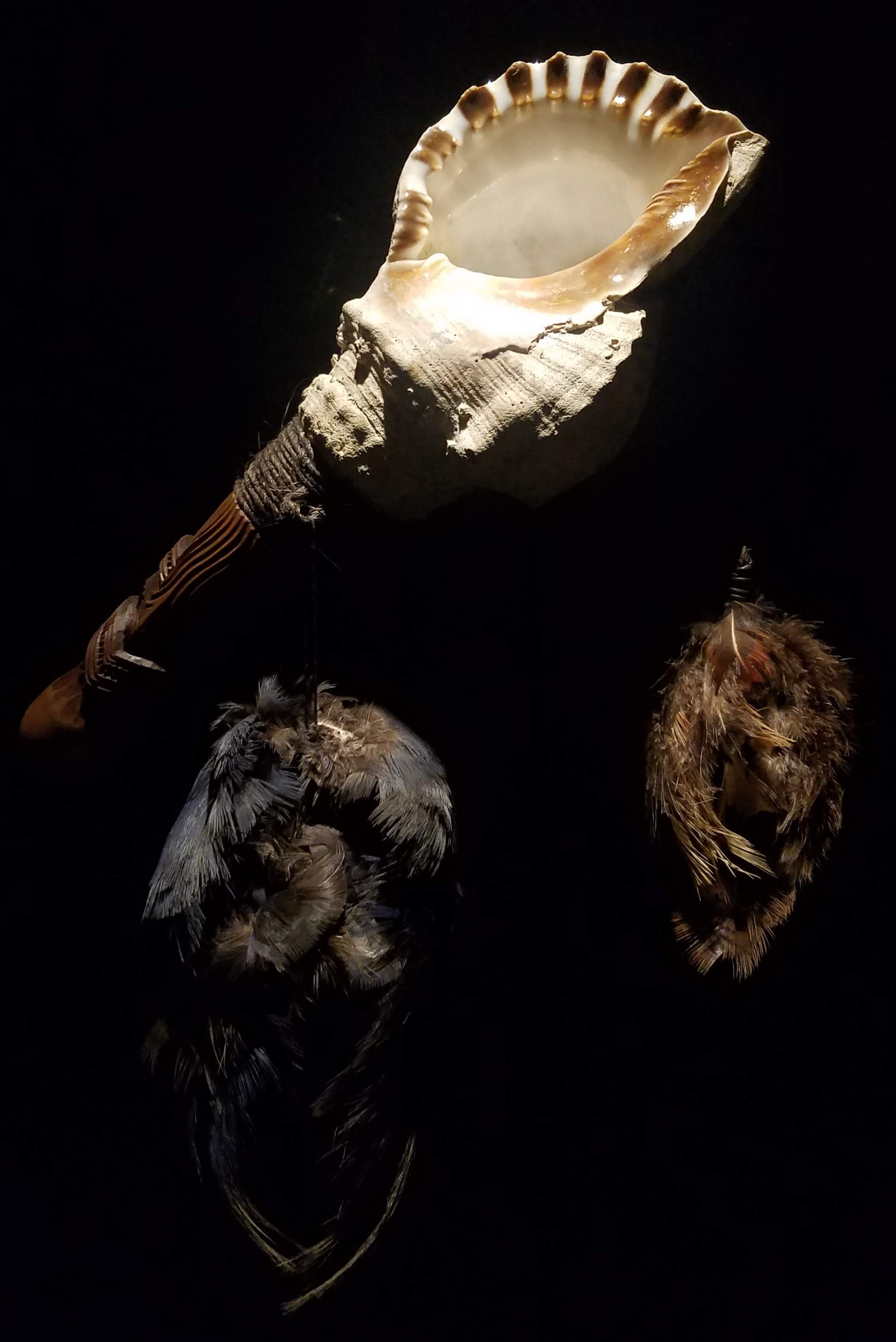

This beautiful pūtātara was created for the Waitangi Museum in 2015 from shell, greenstone, and bird pelts

For Māori in times past, a conversation between strangers began with the sound of pūtātara, a conch-shell trumpet that signaled either a welcome or a warning. How the visitor responded to the call, and to the haka (ceremonial challenge dance) that followed, determined whether the home team would be hospitable or hostile.

When Abel Tasman’s ships reached the shores of these islands in 1642, the sailors heard the pūtātara and responded with shouts and trumpet blasts of their own. Sadly, the dialogue between the two groups soon turned hostile, and it would be more than a hundred years before another European attempted to start a conversation with the inhabitants of Aotearoa. But the Dutch expedition did accomplish something permanent; it gave the land of the Māori its European name: New Zealand.

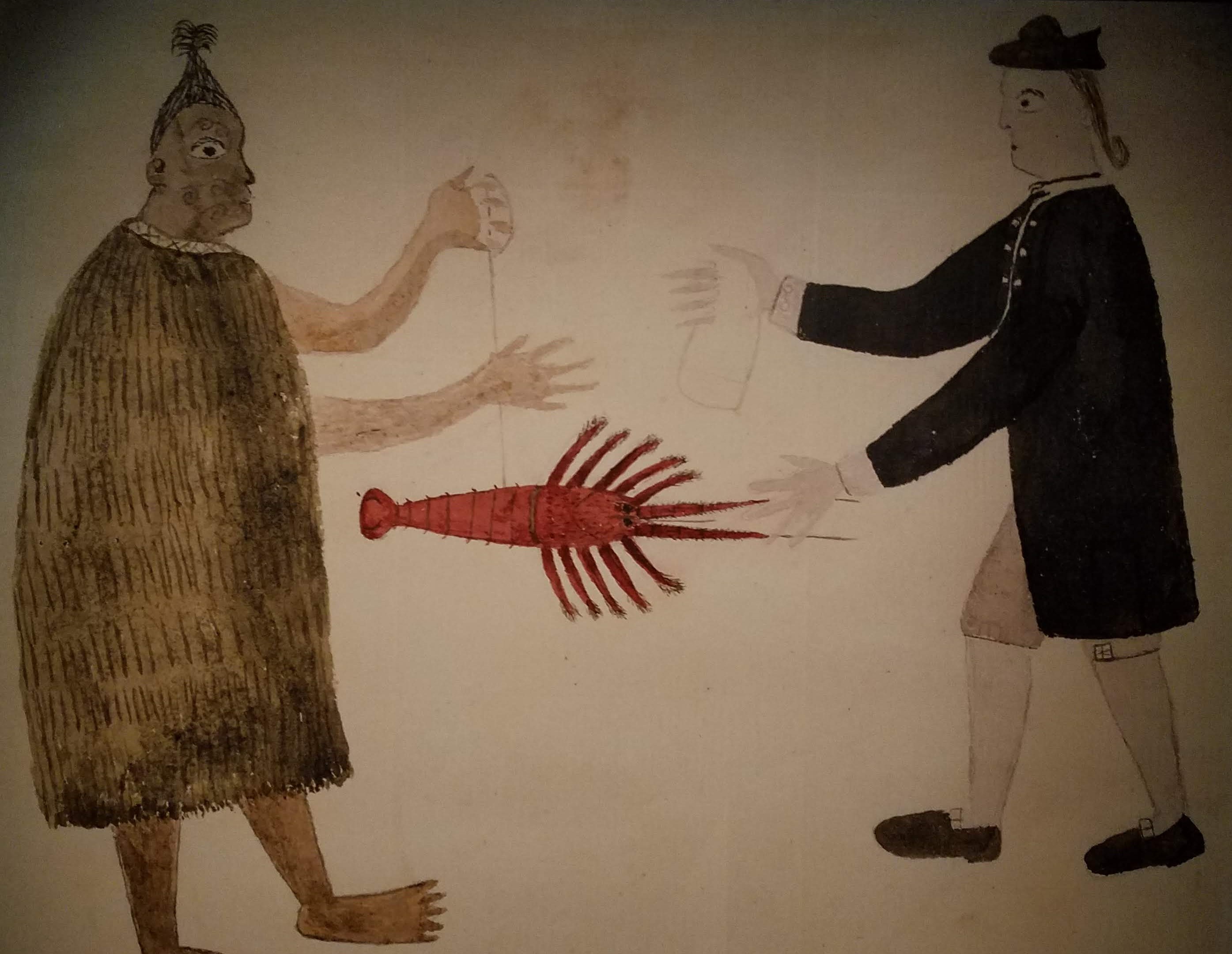

While the next European-Māori encounter was not without some hostility, James Cook enjoyed an advantage over Abel Tasman. Before he left Tahiti in 1769 in search of a southern continent, the Englishman enlisted a Tahitian high priest and navigator named Tupaia to join his expedition. After Cook’s expedition landed in Poverty Bay on the east coast of the North Island, both Tupaia and Māori were astonished to discover that they could understand each other’s language. With Tupaia acting as interpreter, British and Māori were able to begin peaceful conversation and establish a mutually satisfactory trading relationship.

Māori chief and Joseph Banks bartering a crayfish for cloth, a drawing by Tupaia, the Tahitian who accompanied James Cook to New Zealand in 1769

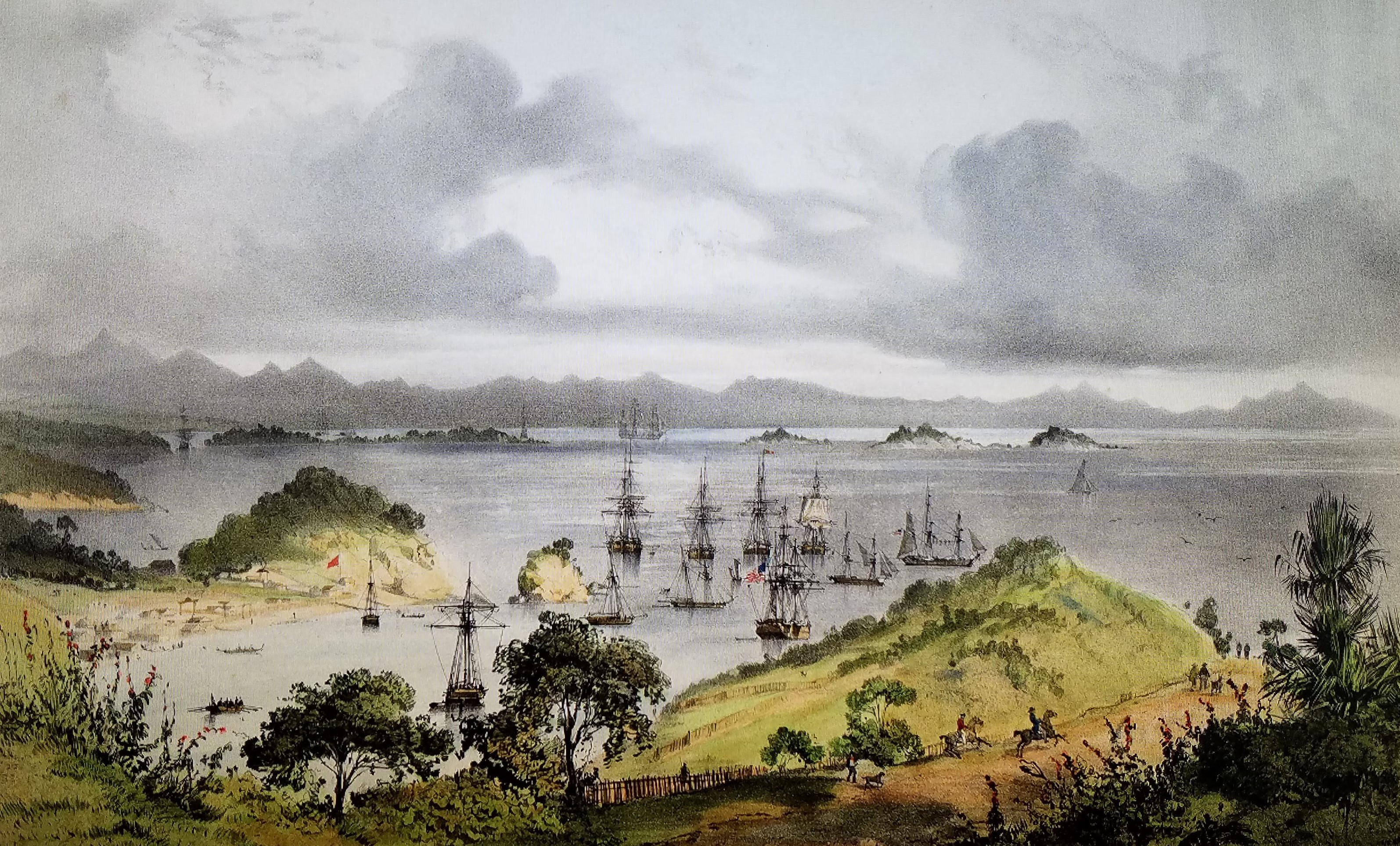

Kororāreka (Russell) Harbour, circa 1835

In the museum, we learned more about how the town of Kororāreka/Russell became an important pioneering outpost as Māori and Europeans learned to live and work together. Similar experiments in Māori-European relations were conducted in other places around the islands. European traders needed food and natural products from the islanders to resupply their ships, while the natives were eager to obtain manufactured goods such as cloth, nails, and scissors from the Europeans.

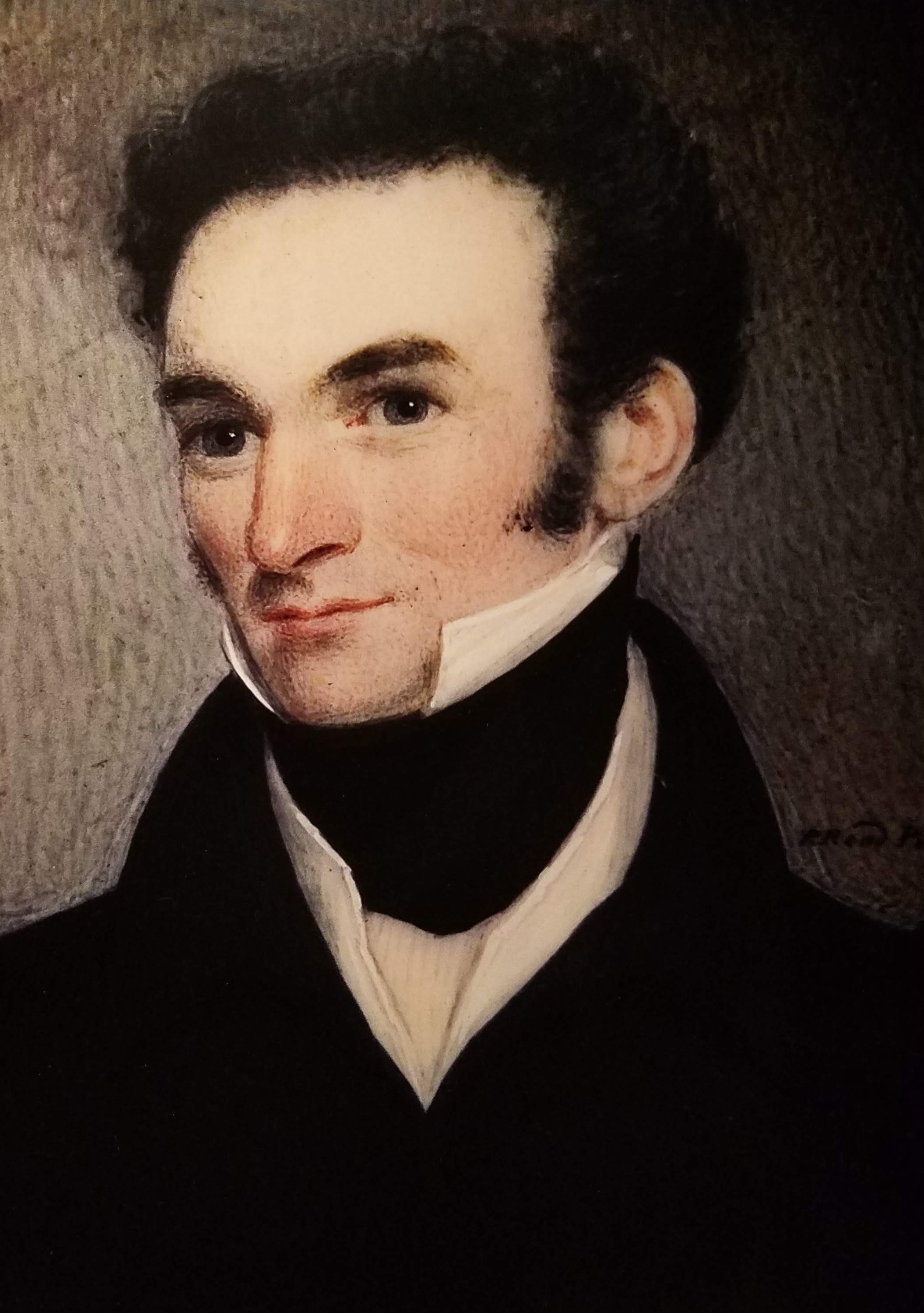

By the 1830s, a robust shipbuilding industry had been established in the Bay of Islands, but because New Zealand lacked official country status, ships built there could not be registered according to international law. That made them subject to confiscation when they entered foreign ports, which angered both Māori and New Zealand-based European traders. James Busby, an English jurist who was appointed British Resident of New Zealand in 1833, proposed that the situation could be resolved if New Zealand had a national flag. To that end, in 1834 he gathered prominent rangatira (chiefs) from several northern hapu together at his official residence in Waitangi and offered three or four different flag designs for them to choose from. They decided to call their choice Te Kara o Te Wakaminenga o Nga Hapu o Nu Tirene (the Flag of the United Tribes of New Zealand). The effects of the flag were far-reaching: not only were ships flying Te Kara now officially recognized, but many Māori hapu (in the north, at least) began to think of themselves as part of a unified political entity. Busby encouraged that line of thinking, especially after hearing rumors that a Frenchman trying to establish a colony in the South Island planned to declare French sovereignty over all of New Zealand. To ward off that threat, Busby called another meeting of Māori rangatira in 1835 and helped them draft the Declaration of the Independence of New Zealand. One of these rangatira was Hōna Heke Pōkāi, a young man who had attended a mission school in Kerikeri, converted to Christianity, and eventually became an important advocate for productive Māori-European relations.

James Busby, British Resident of New Zealand 1833-1840

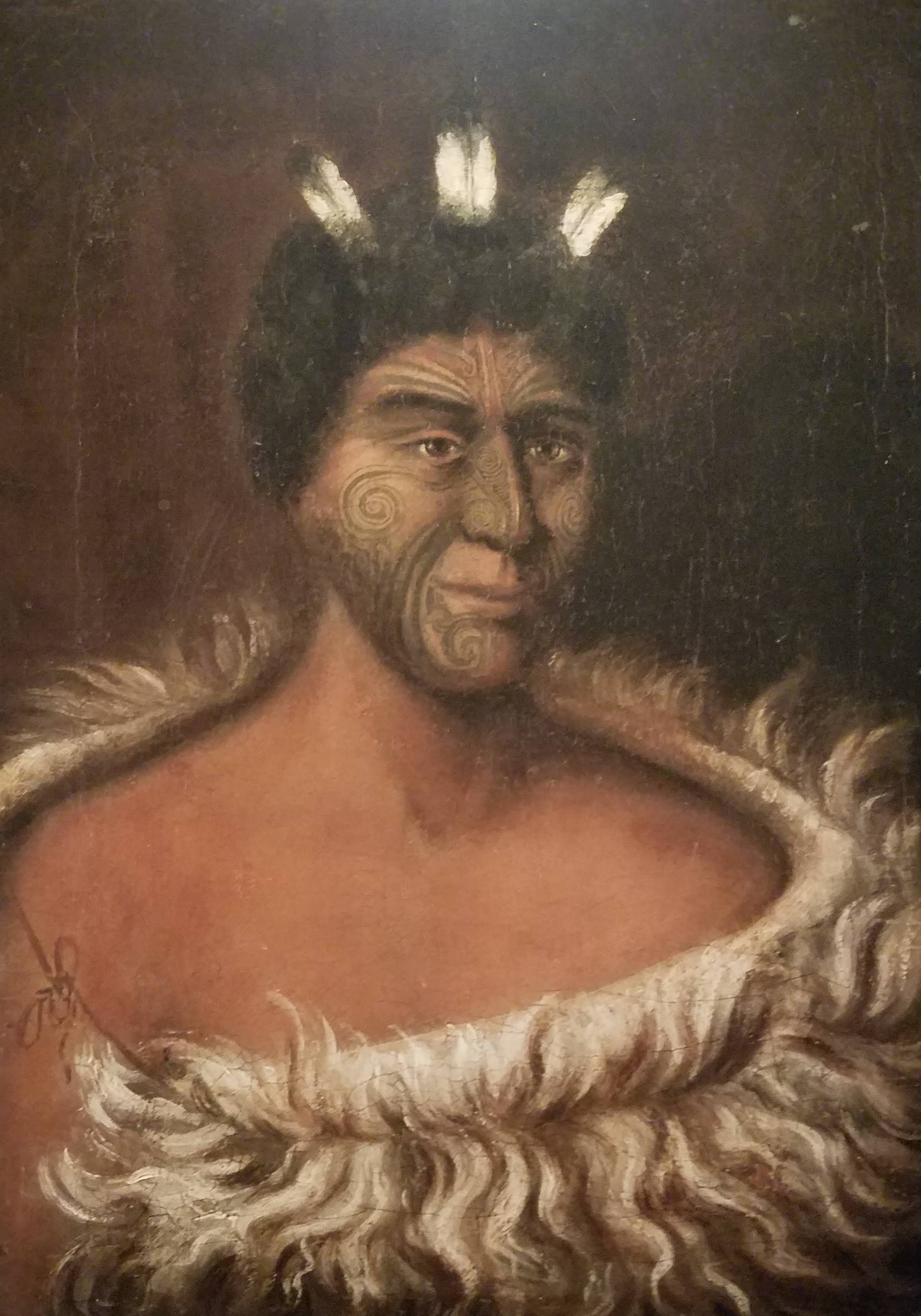

Hōna Heke Pōkāi, one of the rangatira who signed the Declaration of the Independence of New Zealand in 1835

Te Kara o Te Wakaminenga o Nga Hapu o Nu Tirene (the Flag of the United Tribes of New Zealand), 1834

Unlike the American colonists who wanted to dissociate themselves from the British when they declared independence, native New Zealanders sought British support and protection for their new union. They—along with Busby, who had been charged with establishing order in the Bay of Islands, but had been provided no means of enforcing the law—were eager for the British Crown to subdue its unruly subjects. King William IV responded by declaring that he would “continue to be the parent of their infant State, and its Protector from all attempts on its independence.” This was perhaps disingenuous because by 1840, William IV’s successor, Queen Victoria, had declared sovereignty over New Zealand, appointed William Hobson as colonial governor, and sent troops to keep order. Soon after Hobson established an official seat of British government in Russell, he attempted to clarify the relationship between New Zealand and the British Crown by creating a new document for Māori rangatira to sign, which came to be known as the Treaty of Waitangi.

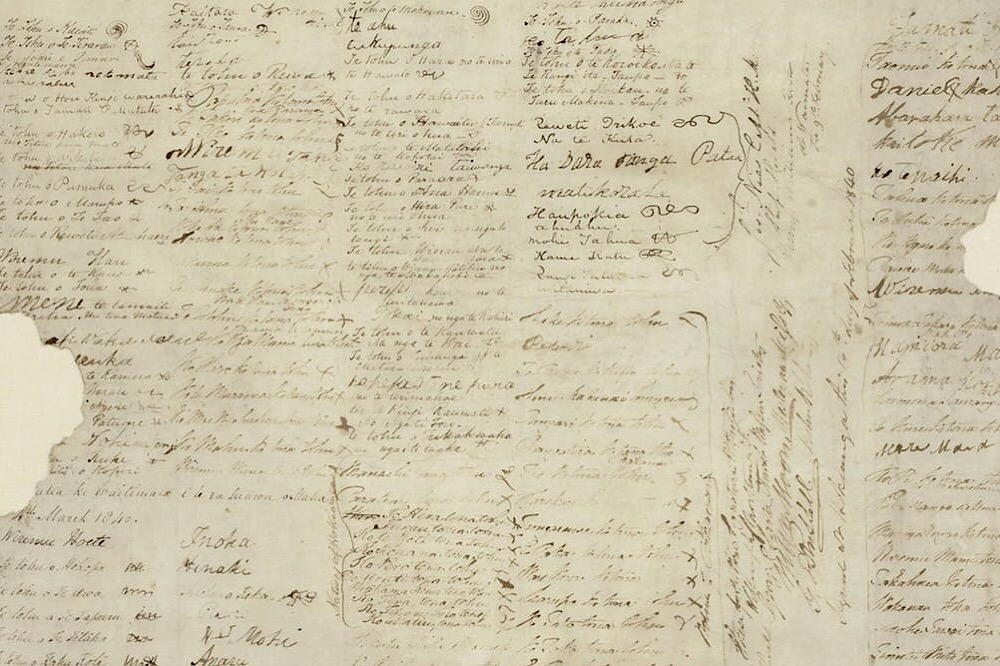

One of a few extant copies of the Waitangi Treaty

Unfortunately, the treaty signed at Waitangi was drawn up in haste (three days) and translated from English into Te Reo, the Māori tongue, in even greater haste (overnight). The two British missionaries Hobson assigned to do the translation did not adequately consider the nuances of either language, especially with regard to the definition and terms of sovereignty. Some say that the British intentionally deceived Māori rangatira by using language in the Te Reo translation that misrepresented what the natives were expected to concede; others attribute the problems to ignorance. But whether the confusion about the terms of the treaty was intentional or not, it led to several years of warfare between the British and Māori iwi who perceived that they had been cheated out of their land. Of course, the British prevailed. (For more about the aftermath of the Waitangi Treaty, read our previous post about visiting the Cambridge Museum.) We were pleased to see that the narrative presented in the Waitangi Museum was very even-handed, encouraging visitors to evaluate the history of the treaty from both the British and Māori perspectives and draw their own conclusions.

Britain’s royal seal affirms the God-given right of its monarch and pronounces “shame on anyone who thinks evil of it”

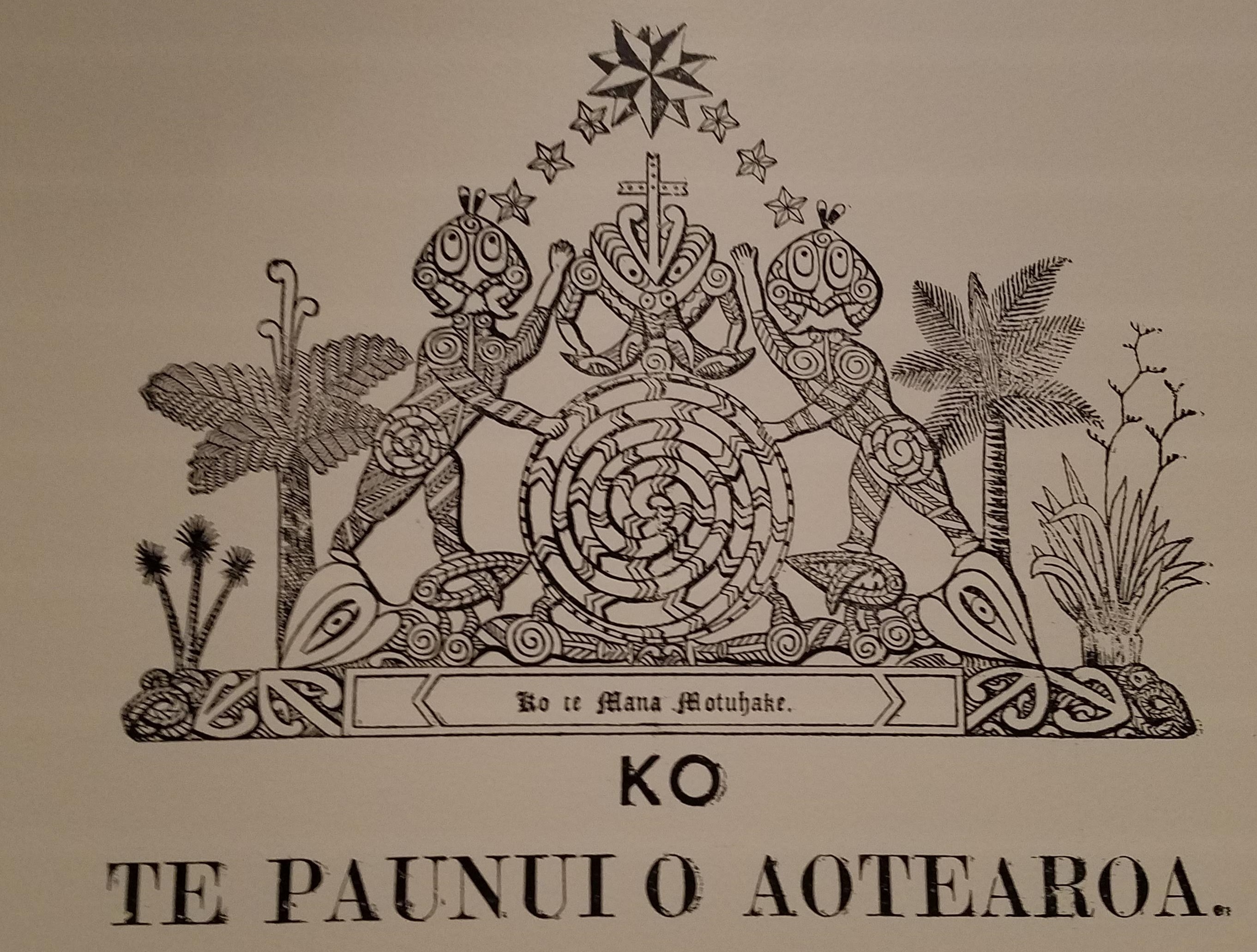

The seal of Aotearoa—Land of the Long White Cloud—asserts New Zealand’s authority as an independent nation

As we continued through the museum, Nancy was elated to discover the answer to a question she had had regarding when and how Te Reo became a written language. Not long after Captain Cook’s expeditions put New Zealand literally on the map, the Church Missionary Society in England began sending Anglican missionaries to “civilize” Māori and convert them to Christianity. In 1814, an English missionary named Thomas Kendall arrived in the Bay of Islands, founded a mission at Kororāreka, and was appointed magistrate by the colonial governor of New South Wales (who had decided that New Zealand should be under his authority). Pākehā like Kendall were keen for Māori to learn English so they could begin teaching them from the Bible, but most Māori, it seems, were interested in learning English mostly so they could more easily communicate with their new trading partners. Māori eagerly sent their children to the mission school not only so that they could become conversant in English, but also so that they could become literate. The concept of reading and writing was a new one to Māori, and they found it fascinating.

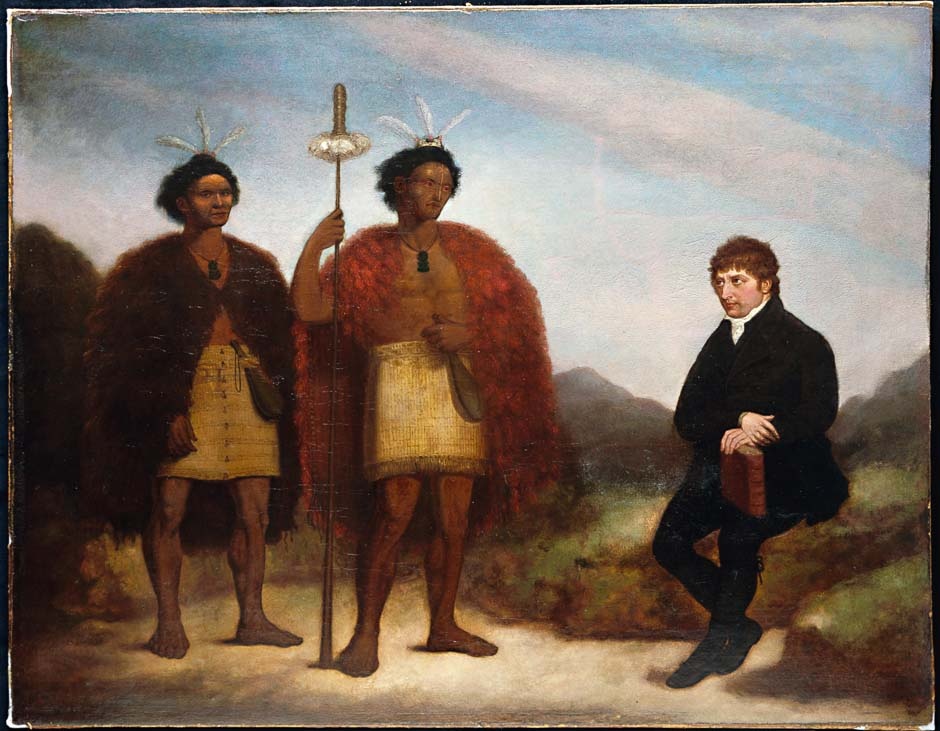

Māori Chiefs Waikato and Hongi Hika in London with the Reverend Thomas Kendall, 1820

Reverend Kendall was not content to simply teach Māori English; he quickly learned Te Reo and by 1815 had published A korao no New Zealand (The New Zealander’s First Book), transliterating Te Reo with the Latin alphabet as best he could. In 1820, Kendall traveled back to England with Hongi Hika, a powerful Māori rangatira whom he had befriended, and a lesser chief named Waikato. During their five-month visit, Hongi was royally received as “King of New Zealand” by King George IV, who presented him with a suit of armor. More importantly, the three met with Samuel Lee, a Cambridge linguistics professor whom Kendall had engaged to produce a standard written form of Te Reo. The product of their collaboration was A Grammar and Vocabulary of the Language of New Zealand, published later the same year.

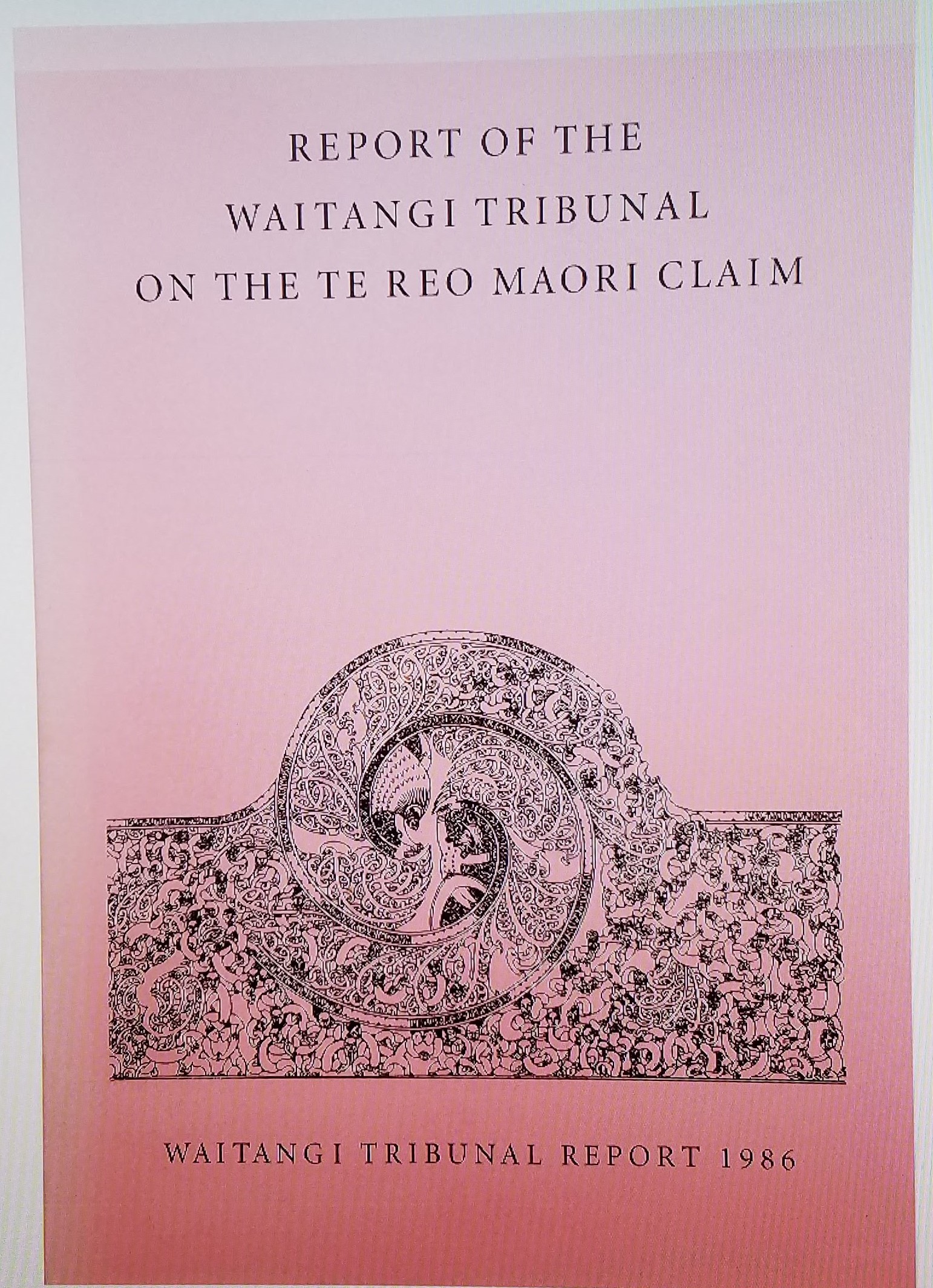

The Waitangi Tribunal report recommending the official restoration of Te Reo (Māori language) to public life

This information led to the answer to another of Nancy’s questions about written Te Reo: Why is the Māori f sound written as wh? Apparently, Samuel Lee accepted the soft wh of Hongi Hika’s northern accent in words like whare (house) and whanau (family) as standard, whereas most Māori actually pronounce those words with a more fricative f.

We at the Matthew Cowley Pacific Church History Centre are particularly grateful to those who taught Māori to read and write and provided a way for them not only to read scripture, but also to record history in their own language. Māori literacy blossomed after the appearance of Lee and Kendall’s Grammar and Vocabulary, producing a valuable trove of books, newspapers, letters, journals, and family histories during the nineteenth century. Sadly, however, as the Pākehā population of New Zealand grew and native Māori were encouraged to learn English and assimilate into the now prevalent European culture, use of Te Reo began to be officially suppressed. Some of the MCPCHC’s volunteer guides have told us that they remember being punished for speaking Te Reo at school during the 1950s and 60s. By the 1970s, the language was in danger of dying out altogether, and traditional Māori culture along with it. Citing the value of preserving the nation’s cultural heritage, several native groups petitioned Parliament to begin promoting Te Reo. The Waitangi Tribunal, established in 1975 to investigate claims that the New Zealand government had violated the terms of the Waitangi Treaty, determined that Māori rights had indeed been disregarded, and recommended the reinstatement of Te Reo in public schools. Te Reo is now thriving once again, used in tandem with English for most public signage, in news media, and in everyday conversation.

We had to interrupt our self-guided tour of the museum when the time arrived for our scheduled guided tour of the adjacent treaty grounds. While we were interested in visiting the actual site of the historic event, we were not terribly excited about leaving the comfort of the museum to slog across an open field in driving rain. Nevertheless, we met our group, unfurled our umbrellas, and followed the guide outside. For the next half hour, she tried to keep us under cover as much as she could while keeping us entertained with interesting and sometimes amusing historical anecdotes.

Ngā Toki Matawhaorua

Before we went out on the treaty grounds, we stopped at the Whare Waka, the shelter under which is displayed the world’s largest ceremonial war canoe, Ngā Toki Matawhaorua. It is 123 feet long and nearly 7 feet across at its widest point, capable of carrying 80 paddlers and 55 other passengers. Ngā Toki was built in 1940 to celebrate the centennial of the Waitangi Treaty, and has been launched in the Bay of Islands with a full complement of oarsmen on Waitangi Day (6 February) every year since 1974, when it was refurbished to allow visiting Queen Elizabeth II to go out for a ride. Elaborately decorated waka (canoes) such as this one are important representations of Māori tribal identity and history, each telling a unique story in symbolic carvings and painted designs.

New Zealand’s three historic flags flap in the wind, marking the spot where the Waitangi Treaty was signed in 1840

As we crossed the wide, wet field of the treaty grounds toward James Busby’s residence, we stopped just long enough to snap a photo of the flagstaff, from which flies Te Kara, the flag of the United Tribes of New Zealand; the Union Jack, which was used in New Zealand from 1840-1902; and the current national flag, which features the stars of the Southern Cross with a small Union Jack in the corner. The original Waitangi flagpole, made from a kauri tree, was given to Busby by Hōne Heke Pōkāi, but it was moved across the bay to Russell sometime after Busby went back to England.

Busby residence where the Treaty of Waitangi was written

We made another brief stop outside the Busby residence, where the group stretched out under the narrow eaves to avoid getting soaked (and to maintain physical distance) while the guide explained James Busby’s role in the unification of Aotearoa’s tribes. Not wanting to stand in the rain any longer, Diane, Michael, and Nancy decided to skip the cultural performance that was to be presented outside Waitangi’s ceremonial Whare Rūnanga (Assembly House) and went back to the museum. In the last rooms of the exhibit, we learned that after James Busby returned to England and New Zealand’s colonial government moved from Russell to Auckland, the treaty grounds were plowed up for farmland and Busby’s residence was abandoned for nearly a hundred years. In 1930, when Charles Bathurst Lord Bledisloe became governor-general of New Zealand, he was dismayed to learn that such a significant site had been totally neglected. Using his own funds, he purchased the estate and then set up a trust to restore the Busby home and establish a national historic site. Bledisloe ensured that the centennial of the 1840 treaty signing was properly celebrated with the launching of the ceremonial waka, and Waitangi Day was declared a national holiday. The impressive museum we were visiting opened in 2016. After learning that the site is administered by the Waitangi Trust instead of by the national government, we could understand why the price of admission is so high.

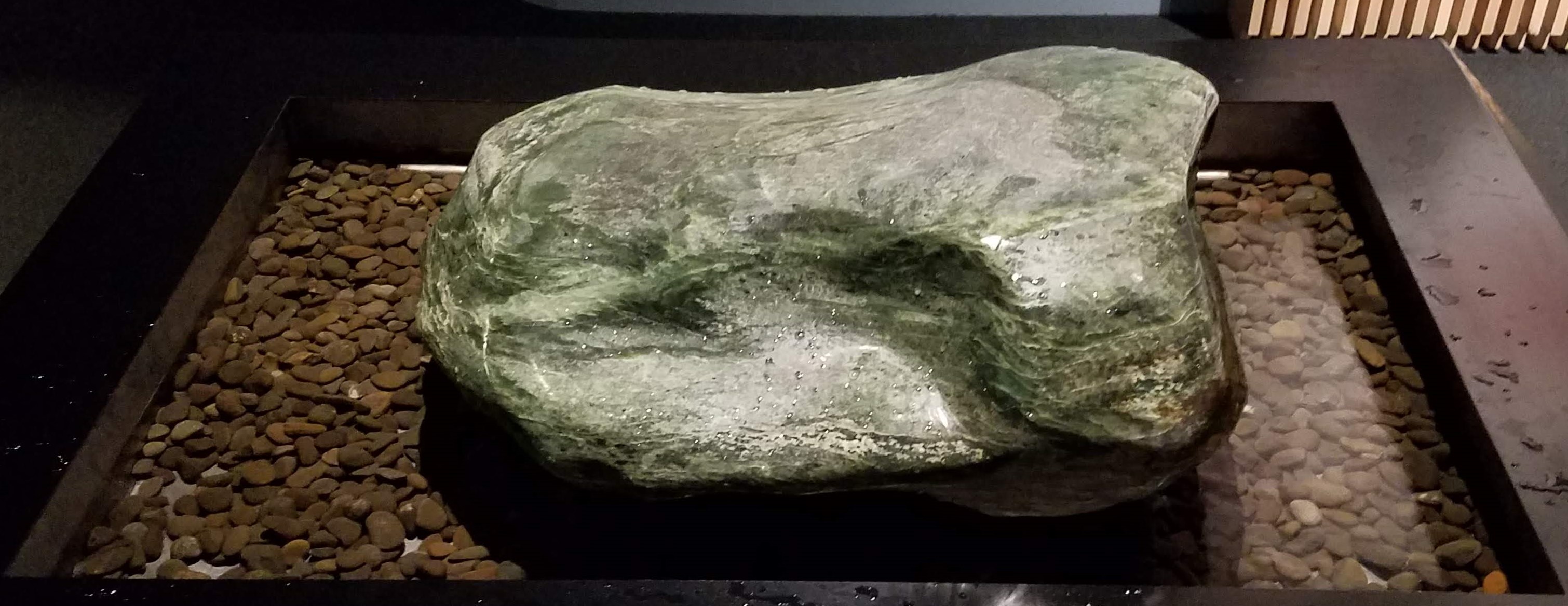

We completed the traditional cleansing ritual by touching the pounamu, dipping our fingers in the pool, and sprinkling ourselves with water

We then completed the modern cleansing ritual by rubbing sanitizer on our hands before leaving the building

The last item patrons see before they exit the museum is a “touchstone” of pounamu (greenstone, or New Zealand jade), said to “embody the spirit of Waitangi.” Visitors are invited to touch the stone, dip their fingers into the pool in which it rests, and sprinkle the water over their head and body. They thus engage in a cleansing ritual traditionally practiced by Māori when leaving a place of tapu (sacredness). The Waitangi Museum is considered tapu because it contains images of ancestors and other historical treasures.

Michael in our suite at the Busby Manor Resort

Rain was still falling as we drove back to the Busby Manor Resort, where Elder and Sister G had spent a warm, dry, quiet afternoon. The kitchen in our suite was furnished with a big table, plenty of dinnerware (much nicer than we have in our missionary flat), and even a dishwasher, so Barry and Eva suggested that rather than going out again for dinner, we could stay home and order take-away from Green’s. That sounded like a fine idea, so this time we chose three different curries from the Indian menu to share. Barry and Michael gallantly offered to brave the rain again to pick up the order. Later, they made another trip to Møvenpick for take-away ice cream, which we ate while playing Ticket to Ride.

St. Paul’s Anglican Church, where James Busby was introduced to the locals as British Resident in 1833. Our suite at the Busby Manor Resort overlooked the churchyard

Monday morning brought the sun again, so we were able to take a few photos and load our cars without getting wet before we headed out of town.

Public toilets in New Zealand are sometimes works of art

Maromaku’s idyllic setting

Besides home, our destination for the day was the Going family’s little chapel in Maromaku. (If you haven’t read our previous post about Paihia, go back and read it now to learn about the Goings.) The village of Maromaku is located about 30 minutes off the main road back to Auckland, nestled among rolling green hills that could have been the setting for Hobbiton. (They weren’t; the Hobbiton movie set is located farther south, about 50 kilometres east of Hamilton.)

The historic chapel, built in 1940 entirely from the wood of one huge kauri tree, was decommissioned as a religious edifice in 1969 when The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints built a standard meetinghouse next door to accommodate a growing ward. The Going family now uses the original chapel as a family memorial and social hall, where historic photos of family members and the rugby teams they’ve played for are on display. One wall features a map showing where many descendants of Percy and Gertrude Going have served missions for The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints since the mid-20th century, a testament to the whanau’s strong foundation of faith and dedication to the Lord.

Before we left the building, Michael had to see if the old (c. 1910) pump organ still worked. It did! (Watch the video below.)

The Goings’ 1940 chapel in Maromaku is surrounded by cow paddocks

The chapel’s wooden floor planks clearly show the crossgrain of the kauri tree

The 1969 meetinghouse across the parking lot

Eva (right) with Barbara C, the Maromaku resident who took us inside the Goings’ family memorial hall

Missionaries from the Going family have served all over the world

Barry and Michael pay their respects to departed members of the Going family at the Maromaku Valley Cemetery across the road from the chapel

Driving back toward Hamilton, it was plain to see that the previous day’s furious rainstorm had wreaked havoc on Northland roads and farm fields. Fortunately, we didn’t encounter any high water on the main highway, but we did pass “Road Closed Ahead” and “Bridge Out” signs at several crossroads. We also encountered no traffic jams—perhaps because high water prevented road construction crews from working that day. We stopped briefly in Whangarei for a bio break, at a Subway in Wellsford for lunch, and were home by 3:30 p.m.

Other than noticing so much flooding, Nancy would have considered the journey home uneventful except for a growing sense of dread. That morning, she had awakened with a slightly scratchy throat; then her nose began to run, and by the time we got home she had sneezed her way through half a box of tissues. (Good thing we had decided to take two cars, and that Diane was riding with Barry and Eva.) Headachy and without appetite, Nancy was sure she had come down with a cold—if not COVID-19—but how? She had scrupulously kept her hands clean, tried to avoid touching her face, and maintained physical distance from everyone except the six other missionaries in our cohort. None of them had any cold symptoms, so where did hers come from?

Obviously, Nancy would not be able to go to work the next day—the first day the Matthew Cowley Pacific Church History Centre would be open to the public after 64 days of closure. Feeling depressed and miserable, she went to bed early and hoped that repeated sneezing wouldn’t keep her awake. Fearing that Nancy’s repeated sneezing would keep him awake, Michael opted to sleep in the living room, even though the only furnishings offering horizontality there are an uncomfortably soft recliner, a 53-inch loveseat, and the floor.

Miraculously, Nancy got a full night’s sleep, sneezing only once that she could recall, and awoke just before Michael left for the Centre, not only feeling fine but also completely symptomless. She stayed home anyway just in case, and spent the day as she had so many before during the past two months: working from home on a laptop. Eventually she decided that the runny nose must have resulted from an allergic reaction to damp and mold brought on by the heavy rain; no other explanation ever presented itself. No matter the cause of Nancy’s one-day illness, everyone was grateful that she was cured so quickly, and that the ailment did not spread to anyone else.

Your account of the Waitangi Museum makes the admission price sound like it was worth every penny.