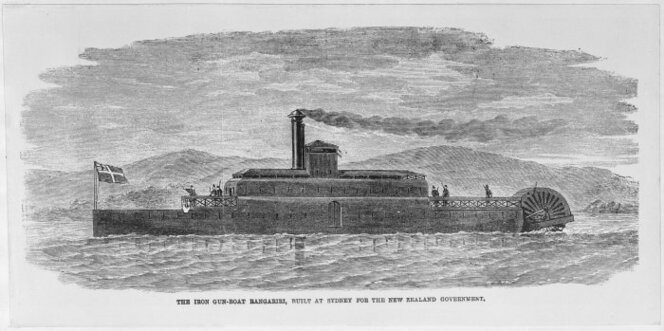

In the 1860s, in the midst of the Land Wars between the Māori Kīngitanga (Kingmen) and those loyal to the British Crown, the colonial government commissioned a gunboat that was specially designed to navigate narrow, shallow stretches of the Waikato River, the North Island’s major inland waterway. Components for the vessel were manufactured in Sydney, Australia, and shipped to Port Waikato, where the river empties into the Tasman Sea.

The iron gun-boat Rangiriri, built at Sydney for the New Zealand Government.” [Illustrated London News, 1864?]. Ref: A-110-008. Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington, New Zealand

In August 1864, the Rangiriri brought the first European settlers to Kirikiriroa, the small Māori village that eventually became Hamilton. Within a few years, the military sold the ship to a commercial firm. It continued frequent runs up and down the Waikato until 1889, when the vessel ran aground near what is now the center of Hamilton. Piece by piece, the abandoned steamer’s engines and other mechanical components were pillaged for installation in other river boats. Eventually, all that was left of the Rangiriri was the iron hull, which remained mostly intact even after it became engulfed in a tangle of vegetation. For many years, daring swimmers used the rusting wreck as a diving platform.

The Rangiriri raised from the river bed

In 1981-82, the Rangiriri, New Zealand’s oldest surviving iron-hulled boat, was raised from the river and placed on the bank. However, exposure to the elements caused further corrosion, so in 2007 the ship was raised to higher ground, and a protective shelter was erected over it. The remains were then cleaned and treated with rust-proofing. Conservation work was completed in 2010.

The Rangiriri Pavilion

The conserved Rangiriri honors the memory of Hamilton’s original Pākehā (European) settlers, militiamen and their families who had been allotted acreage in the Waikato by the colonial government in order to secure its claim to lands confiscated from the Maori. The former soldiers included a number of skilled tradesmen: butchers, bakers, architects, painters, shoemakers, tinsmiths, and even a jeweler. Nevertheless, maintaining a European-style livelihood in Hamilton was difficult because tools and materials were nearly as scarce as paying customers, and transporting such supplies up the river was expensive. Even farming was hard because the land that had been deeded to the settlers was swampy and ill-suited for growing the kind of crops Pākehā favored.

A sculpture representing 10-year-old Sarah Ann Bryant, one of Hamilton’s first Pākehā settlers. Resentful Māori threw peaches at her and the other passengers as the Rangiriri paddled up the Waikato, but Sarah said she didn’t mind because the fruit was ripe and delicious

Among the earliest settlers were at least 900 children. By December 1864, Hamilton’s first school had been established on the west side of the river. The following year, a second school had to be opened for families who lived east of the river because there were no bridges across the Waikato until 1879. (Even though there are now seven bridges spanning the river in the unified city of Hamilton, a distinct cultural divide remains between east and west—not unlike that between Cincinnati’s east and west sides).

Wellington Street Beach

Giant Rhododendron tree . . .

. . . and field of early spring daffodils in August

Completion of a rail line in 1877 from Auckland to Frankton on Hamilton’s west side spurred commercial growth in Hamilton West. (Frankton, the community we live in, was incorporated into Hamilton proper in 1917. We’ll share more about the history of the railway and Frankton Junction in another post.) In contrast, Hamilton East developed more of a genteel character during the 1940s when a suburb of “garden homes” was built on a large tract of land next to the river known as Hayes Paddock. In the 1960s and 70s, the riverbank at Hayes Paddock was developed into a popular bathing spot. We haven’t seen many swimmers at Wellington Street Beach, but probably because we’ve visited only in winter. The original changing house is currently used for canoe storage, but the city is planning to upgrade the facilities over the next few years.

Hayes Paddock offers not only the beach, but also convenient access to the paved walking paths that follow both sides of the river for more than 10 kilometres through the center of Hamilton. Today, in company with Eva and Barry, we walked from Wellington Street Beach to the southern terminus of the path at Hamilton Gardens, then turned around and walked back toward our starting point, where we took a long lunch break at a sidewalk café called Hayes Common. The afternoon was a little chilly, but pleasant enough that we could sit at a table outside and listen to the surprisingly pleasant songs of a magpie that was occupying a nearby rooftop.

Michael ‘s “Melt Toastie” with Barry’s pork belly Bao buns in the background

Hayes Common cafe

We had expected the Hayes Common café to be a standard deli-bakery with an assortment of meat pies and “cabinet salads,” but the menu was much more interesting. Michael ordered the “Melt Toastie”: spinach, mozzarella and fenugreek-gouda cheese on toasted turmeric bread with pickles and onion bhajis (battered and fried, Indian-style) and it was fabulous! Nancy had the equally yummy spiced cauliflower kedgeree (another Indian-style dish) with smoked kingfish, pickled egg, hot-and-sour eggplant, and watercress. Barry and Eva shared with us an order of fries that were anything but ordinary: big chunks of crisp, miso-seasoned potatoes dotted with chopped spring onions and shreds of pecorino cheese. For dessert, we shared a steamed ginger pudding with mulled poached pear, maple syrup, and honeycomb/smoked almond ice cream.

Feeling the need to move again after consuming such a meal, we resumed walking along the river, continuing north to Memorial Park. (See our Memorial Day and ANZAC Day post for a description of our first visit to the park and its war memorials). It was then that we discovered the adjacent Rangiriri Pavilion and learned a little more about the history of the city we live in. As Church History missionaries, we appreciate New Zealand’s efforts to present the stories of its past from the perspectives of both Pākehā and Māori. The PS Rangiriri is a significant artifact from an era of tense interactions between the two groups, and reminds us of how important it is not only to appreciate our heritage, but also to respect others’ views about what happened, no matter how great our differences. So much more can be accomplished if we will make the effort to understand others’ experiences and try to work together in harmony.

My cousin’s husband, Brent Taylor served in New Zealand over 60 years ago. It has been a love for them all their lives and at his funeral he had a Maori send off in Bountiful, Utah. May I include her in your email post?

Thanks, Nancy’s distant Bertelsen cousin,,

Renee Christiansen

Wow! Very interesting