After we consumed our in-room breakfast of yogurt and instant oatmeal, we deposited our key cards at the unattended desk of the Quest Serviced Apartments (leaving our dirty dishes and linens for the invisible servicers) and headed out of town. On Sunday, we had driven the Southern Scenic Route from Dunedin to Invercargill; now (Tuesday 29 December) we picked up the same route and followed it along the coast to Tuatapere, where it turns north along the eastern edge of the Fiordlands.

After we consumed our in-room breakfast of yogurt and instant oatmeal, we deposited our key cards at the unattended desk of the Quest Serviced Apartments (leaving our dirty dishes and linens for the invisible servicers) and headed out of town. On Sunday, we had driven the Southern Scenic Route from Dunedin to Invercargill; now (Tuesday 29 December) we picked up the same route and followed it along the coast to Tuatapere, where it turns north along the eastern edge of the Fiordlands.

The Oreti River bisects the Southland Plain

For weeks we had worried about encountering inclement weather during our tour of the South Island, but once again we were blessed with sunshine and unobstructed visibility for miles and miles across the Southland Plain. The view from the van windows during the first hour of our drive may have been the same one Frodo and his companions enjoyed as they tramped across Eriador toward the Misty Mountains in Lord of the Rings, but the landscape changed as we neared Fiordlands National Park. This is Fangorn Forest territory; indeed, the Fangorn scenes in the LOTR films were shot in the park, which encompasses 1.2 million hectares (4600 square miles) of rainforest and rocky cliffs, lakes and fiords.

The sheep apparently don’t appreciate their view of the Southern Alps across the Southland Plain

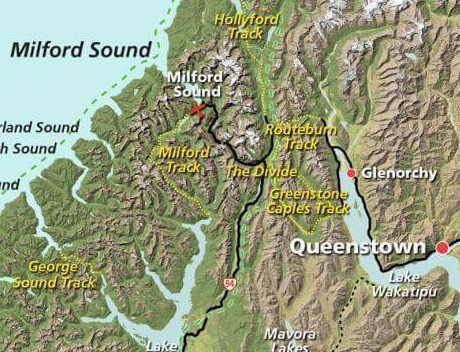

A map of New Zealand’s fiordlands will tell you that nearly all the ocean inlets in this area are called sounds rather than fiords, but whoever named them was mistaken. Both terms refer to valleys that have been filled with seawater, but a sound is a valley formed by a river, whereas a fiord is a valley created by a glacier. Sounds generally have more gently sloping sides than fiords, which tend to have steep walls. The inlets of Fiordlands National Park were formed by glaciers, and the scenery here is some of the most dramatic in the world. Warmer and wetter than the fjordlands of Norway (note the difference in spelling; Kiwis have anglicized the Norwegian word), the region averages an astounding 7 metres of rainfall each year. (Yes, you read that correctly: 7 metres!) In fact, so much rain falls here that there’s a 6-7 metre (20-25 foot) layer of freshwater on top of the saltwater where the fiords meet the Tasman Sea.

Early Māori came to the fiordlands to hunt, fish, and collect tangiwai (a precious stone similar to greenstone and jade, but more translucent), but didn’t establish any permanent settlements because of the forbidding terrain and the rainfall. Neither did the Europeans who came later, although whaling ships used the fiords as convenient shelter from rough seas. A few attempts to set up mining operations were unsuccessful, and despite the abundance of beech trees, loggers never even tried to overcome the obstacles presented by the topography. As a result, most of the fiordlands, a UNESCO World Heritage site, remain untouched, largely inaccessible except by boat, helicopter, or foot.

When we visited New Zealand in 2014, we spent three grueling but glorious days backpacking through the mountains at the northern end of Fiordlands National Park on the Routeburn Track, one of the country’s “Great Walks.” Following that adventure (which you can read about here), we took an overnight cruise through Doubtful Sound, the largest of the fiords, hoping to enjoy the sights from the water. From the boat, we could see plenty of water, but not much of anything else. tt rained the entire time, with fog so dense we could hardly see the deck railing unless we were standing next to it. (Click here for more of that story.) We can’t say we hadn’t been warned; in the fiordlands, rainy days outnumber dry ones two to one.

Lake Manapouri, which we had to cross by boat in 2014 to get to Doubtful Sound

Peaks and valleys in the Wick Mountains along Highway 94

Homer Saddle, which divides the Wick Mountains from the Darran Range

Inside Homer Tunnel

This December day would be different. When the Southern Scenic Route turned east at Te Anau, we continued north on State Highway 94 toward Milford Sound. Leaving the designated Scenic Route did not mean that the view from our windows became any less interesting, however. For the first half hour or so, we skirted the eastern edge of Lake Te Anau, the largest lake in the South Island. The lake surface is about 200 metres (650 feet) above sea level, but soon Highway 94 began climbing into the mountains and we found ourselves surrounded by magnificent 1500-metre (5000-foot) peaks. We would have liked to stop and take photos along the way, but the narrow road seemed to be totally devoid of places to safely pull over. (Later we learned that Highway 94 is one of the most dangerous roads in New Zealand, with a crash fatality rate nearly twice the national average.) The photographers in our van finally had a chance to get some good shots when traffic came to a complete halt for about twenty minutes outside Homer Tunnel, a 1.2-kilometre (0.75 mile) passage cut through solid granite that provides the only direct vehicle access to any of New Zealand’s fiords.

About 18 kilometres beyond the tunnel, Highway 94 terminates at Milford Sound. While it is undoubtedly highway access that has made Milford Sound the most visited fiord in the region, Milford’s stunning scenery has made it one of the top tourist destinations in the world. Reaching 15 kilometres (9 miles) inland from the Tasman Sea, the fiord is defined on both sides by towering rock walls 1,200 metres (3,900 feet) high.

Milford Sound in relation to Queenstown and the Routeburn Track

Early Māori seafarers who explored the fiords learned that this inlet, which they called Piopiotahi, offered abundant fish and seals. After generations of experience with local weather and tidal patterns, Māori learned to safely navigate in and out of the fiord to obtain what they needed. In contrast, European explorers initially avoided Milford Sound because its narrow entry did not appear to lead into a harbor large enough for their vessels. Ship captains such as James Cook, who bypassed Milford Sound for just this reason, also feared entering a narrow inlet with such steep walls, afraid that wind conditions would prevent escape. So it was not until 1812 that a European ship ventured into Milford Sound. Its captain, John Grono, named the sound after the Welsh hamlet he had come from.

Inside our chalet at the Milford Sound Lodge

Despite the delay getting through Homer Tunnel, we arrived in the village of Milford Sound sooner than expected. It was too early to check into our rooms at the lodge, but we left the van in the carpark and walked over to the dock, where we enjoyed an incomparable view of Mitre Peak until it was time to board the boat that would take us into the fiord.

The “Lady Bowen” cruiser

Mitre Peak

The sack lunches we had ordered as part of our cruise package were waiting for us on board: a wrap with a good, crunchy filling; cheese and crackers; an orange; and an apple. Even though the day was clear, we weren’t sure what conditions to expect while we were out on the water, so we found an indoor table next to a window with a good view and made that our base for the afternoon.

The cruise took us around the perimeter of the fiord, close enough to the rock walls that those on deck could almost reach out and touch them. A few of those on deck also got a good soaking when the ship approached Fairy Falls, one of several waterfalls along the route. We cruised out to Anita Bay, where Milford Sound meets the Tasman Sea. There we could feel an obvious difference between the relatively smooth water within the fiord and the choppier ocean surf.

Waterfall Gallery

- Stirling Falls

- Fairy Falls

- Bowen Falls

Milford Sound Gallery

Seals dozing on the rocks

Dale Point, where Milford Sound meets the Tasman Sea

Harrison Cove

Milford Sound Discovery and Underwater Observatory

Underwater observation deck

We’re still not sure why the lacy white marine organisms we saw are called black coral

Barry, Eva, Diane, Nancy, and Michael back on land

On the return trip we hugged the opposite shore, passing more waterfalls and a score of seals sunning on Seal Rock. In Harrison Cove, we stopped and disembarked at the Milford Sound Discovery Centre and Underwater Observatory. This is a floating structure that allows visitors to descend 10 metres (32 feet) below the waterline to look at marine life in its natural environment. It was like visiting an aquarium, except it was we humans who were secured within a glass enclosure.

Back on land after our three-hour cruise, we checked into the Milford Sound Lodge, unloaded our luggage, and relaxed in our own chalets until it was time for dinner in the lodge’s Pio Pio restaurant. Recall that the Māori name for Milford Sound is Piopiotahi, which means “a lone piopio.” The piopio was a medium-size native bird that became extinct in the late nineteenth century, the victim of introduced predators such as rats and stoats. It is said to have had the sweetest song of any bird in New Zealand—which is saying a lot, because we have heard some extraordinarily beautiful birdsong during our rambles around this country. Māori named Milford Sound for the bird because, according to legend, a single piopio was seen flying into the fiord to mourn after the demigod Maui died in an attempt to achieve immortality for humankind.

Venison with green beans and a purée of root vegetables

King salmon with citrus risotto and asparagus

Cheesecake with kiwifruit on a shortbread crust

Dark chocolate mousse with a hazelnut crust, and raspberry and passionfruit sauces

The host at Pio Pio led our party of five to a private room at the back of the restaurant, then handed us menus on which every single thing sounded absolutely amazing (except the green-lipped mussels; we’d had our fill of those the previous evening). Nancy ordered potato-leek soup (which she shared with Michael), followed by grilled venison with green beans and a purée of root vegetables; Michael ordered a salad of pickled beetroot with walnuts and goat cheese (which he shared with Nancy), followed by king salmon with citrus risotto and asparagus. For dessert, Nancy enjoyed cheesecake with kiwifruit on a shortbread crust, sprinkled with powdered beetroot. Michael was surprised that the chocolate mousse he ordered was stiff, like a truffle, but any initial disappointment melted away as he savored the dark chocolate, the hazelnut crust, and the raspberry and passionfruit sauces. Yum!

After dinner, Diane, Eva, and Barry carried extra chairs over to our chalet so we could play a game of Five Crowns. We completed all eleven rounds and then decided it was time to call it a day. And what a day it had been!

All of us expressed wonder and gratitude to God for bestowing another day of perfect weather in a region that sees so few days of sunshine. Perhaps we have overused words like stunning, astounding, spectacular, magnificent, and breathtaking to describe what we’ve seen in New Zealand, especially in the South Island, but even those descriptors can’t adequately convey our impressions of the natural beauties of this country. Not even pictures can capture the full extent of the landscape, the sea, or the sky here. You’ll just have to come and experience it for yourselves.

What a treat for us that you share every aspect of your travels with us. Flora, fauna, food and fun – keep it up, please!

Your pictures you have shared are absolutely breath taking!!! What an adventure for the two of you!

What a fantastic experience you are having. It makes me want to travel to New Zealand IMMEDIAtELY! Thanks for sharing.