Concept

Tuhikaramea before development

Two days after we arrived in New Zealand, Elder and Sister G, who were then the directors of the Matthew Cowley Pacific Church History Centre, showed us a PowerPoint presentation they had prepared about New Zealand’s labor missionaries. It was a story we had never heard before.

In 1948, the First Presidency of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints approved the building of a boarding school for secondary students in New Zealand. The college was to be coeducational and open to anyone, LDS or not. Land was procured in an area southwest of Hamilton known as Tuhikaramea, and by the end of 1951, plans had been drafted and the property surveyed.

Quarry in Whatawhata, west of Hamilton

Kaikohe Sawmill

It quickly became apparent, however, that in post-WWII New Zealand both the equipment and building materials necessary for such a project were in short supply. The Church, which intended to construct a new meetinghouse for the Auckland Branch as well as the school, had to import heavy equipment from the U.S, and responded to the materials shortage by creating its own supply chain. A quarry near Hamilton was procured to provide the sand and crushed rock needed to produce concrete for building blocks, while acres of timberland and a sawmill in the Northland region were purchased to provide lumber for doors, window frames, and cabinetry.

A bigger challenge remained: developing a reliable labor force. New Zealand had lost a significant percentage of its young men in the war—more per capita than any other nation in the British Commonwealth—and those who survived were largely unschooled and unskilled. The Church managed to hire six experienced workers to erect the Auckland chapel, but soon found that the men could not be depended on to show up on a regular basis. Progress on the building was very slow, and the construction supervisor began to despair. If he couldn’t keep the meetinghouse project on schedule, how much longer might it take to complete the multi-unit college complex? And even if he could find more dependable skilled workers, how could the Church afford to pay enough of them for the massive project that lay ahead?

When the supervisor called a meeting to discuss the problem of absenteeism with his crew, one of the workers suggested that perhaps the solution was to abandon the employer/employee model and use the Church’s volunteer missionary model instead. Volunteers were already in use for some Church building projects in Tonga and Samoa so the idea wasn’t entirely new, although none of those workers had been officially called as missionaries. After some discussion, the New Zealand crew agreed to accept the missionary concept. “We are working for money,” they said. “If we choose not to work, we just don’t get paid. Now if we had a Church calling to do this work, it would be different. We would never let the Lord down if called to serve as missionaries.” Thus the six crew members were promptly fired from their jobs and then set apart by the mission president as labor missionaries. Not only did the idea of calling labor missionaries solve the problem of absenteeism, but also the problem of recruiting enough workers to build the boarding school. (Adapted from accounts by Maurice Pearson and Robert L. Simpson, quoted in More Than Bricks and Mortar: An Account of the New Zealand Labour Missionary Programme by Wendy Biesinger Thacker, 2017, pp. 36-37.)

A typical Hui Tau

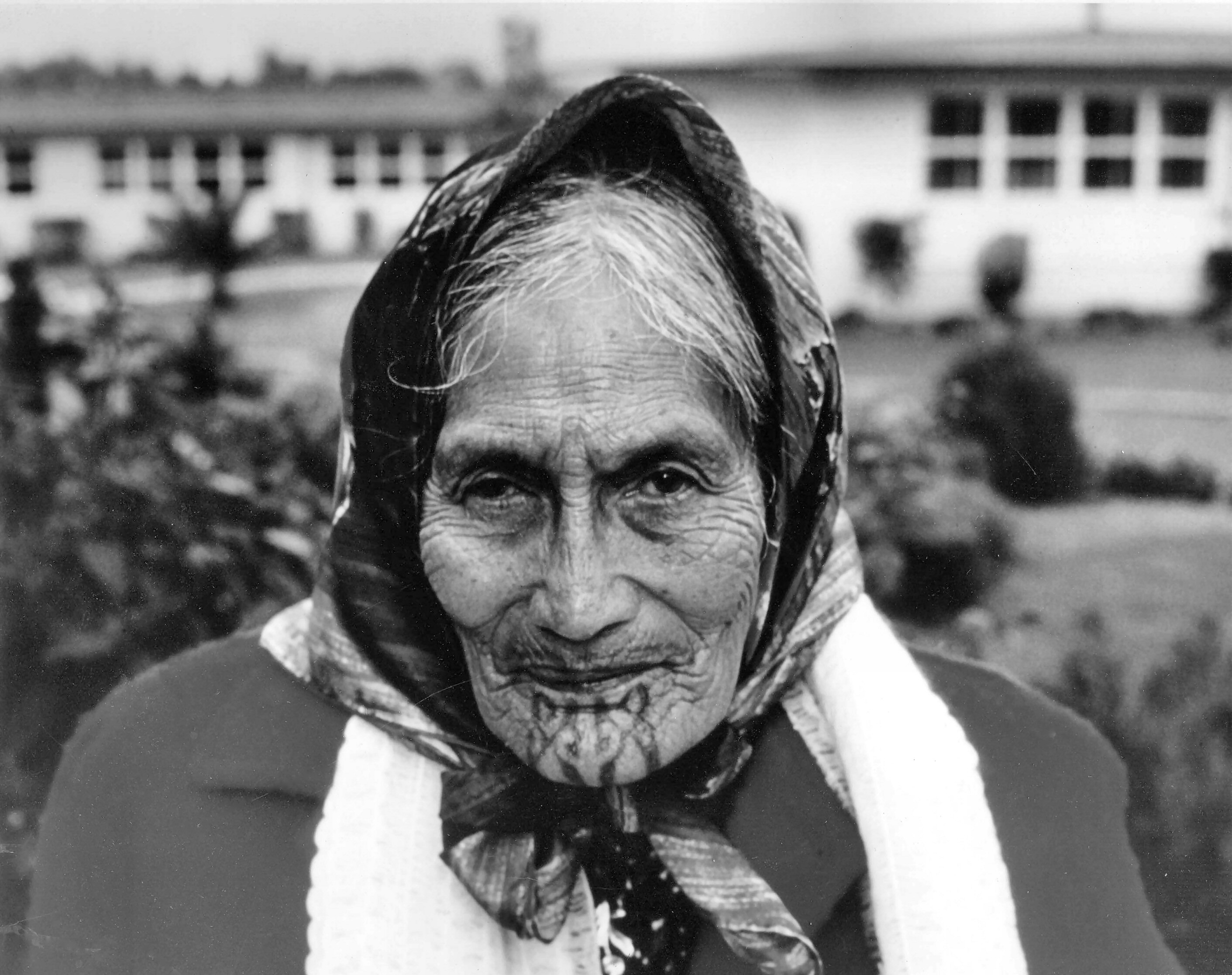

Nanny Raiha, the camp’s chief cook

A machine for making concrete blocks was imported from the U.S.—the first such machine in New Zealand

During the annual hui tau (national Church conference) in 1952, the mission president and construction supervisor explained the proposed labor missionary program to thousands of Saints who had come to the conference from all over New Zealand. Young people would be called to “The Project” in Tuhikaramea as full-time labor missionaries for a period of two years. The Church would provide construction materials and equipment if congregations across the country would agree to support the missionaries by donating food, clothing, and money to cover miscellaneous expenses. The third strategic prong of the program was for experienced tradesmen from North America also to be called as missionaries; they would become crew chiefs, overseeing and training the laborers assigned to their teams. When a sustaining vote was taken, Church members gathered at the hui tau unanimously raised their hands to support the proposal, and by the end of the conference, about forty men had volunteered to serve as labor missionaries. An older woman who had recently lost her husband offered to go along to cook for the other volunteers.

Joinery

Single men lived in bunkhouses

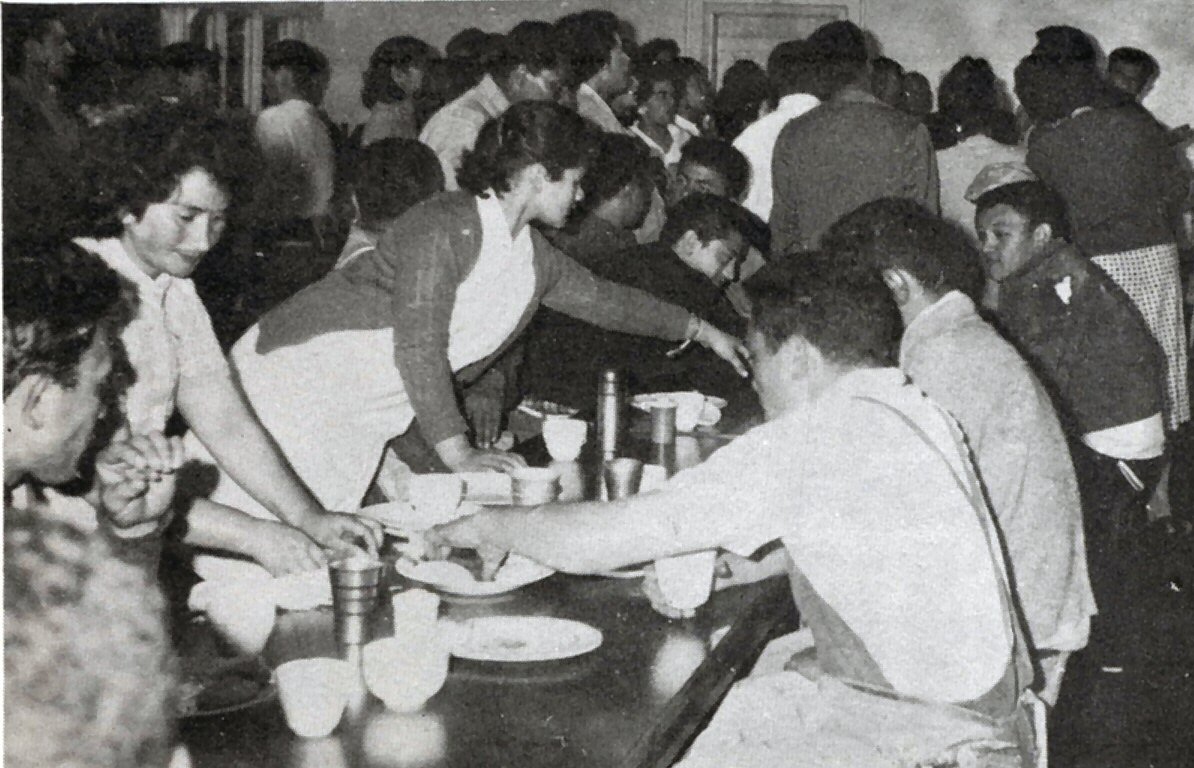

Communal meals were served in the Kai Hall

Married couples lived in tiny “baches”

Missionary “boys” rest from their work on the Sabbath

The new missionaries’ first task was to construct a joinery on the Tuhikaramea site to process lumber and manufacture fittings for the Auckland chapel. Next came housing for the married men with building experience who had been called to serve on The Project. Most of these left thriving businesses and comfortable homes, bringing their families to live at the construction camp in small, unheated cabins known as “baches.” Bunkhouses, affectionately called “chicken coops,” were erected for the single men. Meals were served in a communal dining hall and everyone shared the common toilet and bathing facility. By 1953, 83 single labour missionaries, 14 married couples, and 2 North Americans (plus their family members) were living onsite, and The Project had begun in earnest.

Providing for the laborers working in Tuhikaramea was an ongoing challenge for Church members in other parts of the country, most of whom were struggling to support themselves as well as the volunteers. Food donations arrived at the construction camp irregularly, so watery soup was often the only item on the workers’ menu, and when food ran out general fasts were declared. The missionaries and their families responded with prayer, faith, and no complaints. Wet weather and Tuhikaramea’s swampy ground added to The Project’s degree of difficulty; nevertheless, the laborers persisted and the work progressed.

President McKay shares his vision for The Project

CCNZ’s indoor pool was the largest in New Zealand at the time

The David O, McKay Building’s 2500-seat auditorium

In 1955, amid concerns at Church headquarters in Salt Lake City that The Project was beset by serious cost overruns, Church president David O. McKay decided to go to New Zealand himself to see what was happening. His concerns evaporated when he saw how well the labor missionary program was working despite the challenges, building not only sturdy structures but also skilled, dedicated workers. Moreover, he was impressed by the spirit of unity, love, and religious devotion that pervaded the construction camp. Instead of scaling The Project back as the Church’s finance department had advised, President McKay decided to enlarge it, increasing the number of students the school could accommodate and adding an administration building, a library, and a huge facility that would include a gymnasium, an indoor pool, and a 2500-seat auditorium.

Lined up to pour the foundation of the temple

The temple’s baptismal font takes shape

That was not all. To everyone’s surprise, shortly after President McKay returned to Salt Lake City, he announced that The Project also would include a temple, the first in the Southern Hemisphere. Church members throughout New Zealand and Polynesia were ecstatic, and the announcement prompted scores of new volunteers to come and serve as labor missionaries. It also prompted Saints in Samoa, Tahiti, Tonga, and other island nations to help raise money for The Project. Ground was broken for the temple on the hill adjacent to the college site in December 1955. Less than three years later, both the college and the temple were ready for dedication, products of the earnest efforts and unwavering faith of the South Pacific Saints.

As Elder and Sister G (Barry and Eva) related this story, including snippets of videotaped interviews with former labor missionaries who had lived the experience, we were dumbfounded. How could we have never heard it before? Why was this tale of incredible faith, dedication, and sacrifice not as familiar to every member of the Church as the story of the Mormon pioneers who crossed the American plains? Since becoming directors of the MCPCHC in February 2019, Barry and Eva had discovered that even many New Zealanders were unfamiliar with the history of the labor missionaries who built the Church College of New Zealand and the Hamilton New Zealand Temple, so they had begun developing plans to share the story in a new museum exhibit. And now they wanted us to help.

Over the next several days, Elder and Sister G explained their vision to us. The new exhibit would replace the Light and Life photography show then occupying the gallery at the entrance to the museum, and they wanted it to be ready in time for the reopening of the temple, which had closed in 2018 for extensive remodeling. (A date for the reopening had not yet been announced, but was expected to be in July 2021.) The name Barry and Eva had chosen for the new exhibit was “Sacrifice and Consecration” because they wanted to focus not on The Project’s physical construction, but on the way dedicated participation in The Project had prepared a people worthy of the blessings of the temple. While they wanted to highlight the efforts of the labor missionaries, the Gs didn’t want to overlook the contributions of faithful Church members throughout New Zealand who made sacrifices of their own to support the builders, nor did they want to forget the humble Saints in other parts of the Pacific who overcame tremendous obstacles to attend the New Zealand Temple once it had been completed. They hoped the exhibit would instill gratitude for such a legacy of faith in descendants of the labor missionaries, and inspire others to consider what they might be willing to sacrifice to show similar devotion to God.

The first step on the road from concept to exhibit installation was to convince our advisers at the Church History Museum in Salt Lake City to come along with us—and to secure funding for the trip. It wasn’t a hard sell. Tiffany, the CHM’s education curator who had helped to train us, was enthusiastic and immediately offered to assist in the development of a formal proposal. Barry and Eva had already come up with an idea for structuring exhibit content in three thematic sections, but Tiffany explained that we would need to provide more detailed descriptions of each section and its “key messages.” Barry and Eva asked Nancy and Michael to help them solidify their ideas for the section headings and key messages, and then directed Nancy to write a draft proposal. To help with that assignment, Tiffany supplied some examples of proposals for previous exhibits at the Salt Lake museum and specific suggestions for how to proceed. Nancy’s initial draft was well received, and after some additional refinement Tiffany transformed it into a concise, professionally formatted document to present to the executive branch of the Church History Department and its ecclesiastical supervisors.

By the end of February 2020, our proposal had received official approval and the necessary funding had been granted. We were off and running.

Research

Anticipating that the project would be approved, Nancy, Eva, and Tiffany had already begun research. Nancy dove into books, journals, and other documents about the labor missionary experience to collect compelling stories that illustrated our key messages; Eva reviewed dozens of recorded interviews with former labor missionaries, noting particularly informative or poignant segments; and Tiffany rifled through the Church History Catalog to find relevant images and artifacts to include in the display. (Michael, meanwhile, was working to impose order on the mixed-up files of the MCPCHC to make it easier for the others to locate what they needed.) The three women quickly discovered that there was no shortage of material, largely thanks to Rangi and Vic’s collection efforts over the past thirty years. The Parkers not only had gathered photographs and papers from former labor missionaries but also captured their recollections on video during periodic labor missionary reunions. Our greatest challenge, it seemed, would be to decide which of all the possibilities would most effectively help museum visitors appreciate what faithful Saints had been willing to lay on the altar as they built CCNZ and the temple during the 1950s.

Eventually, because we wanted to include stories about Saints in other parts of New Zealand who sacrificed to support the labor missionaries, and also about those in other countries who sacrificed to travel to the temple, we were faced with the additional challenge of hunting down that type of information. We should also mention that within a month after we got approval to proceed with the exhibit, COVID concerns prompted Church leaders to suspend all in-person meetings and drove New Zealand into Level 4 lockdown. Not long after discontinuing public meetings, the Church closed all its worldwide facilities, so none of us had access to any historical records that had not yet been digitized and had to conduct all our research via whatever secure but slow internet connections we could set up at home.

Despite the difficulties, Tiffany (or maybe it was Eva) found an Ensign article that mentioned a couple from Papua New Guinea who had been the first converts from that country to receive their temple ordinances, coming to the New Zealand Temple in 1984. “They must have an interesting story to tell,” Nancy and Eva decided, so Nancy set out to discover what it was.

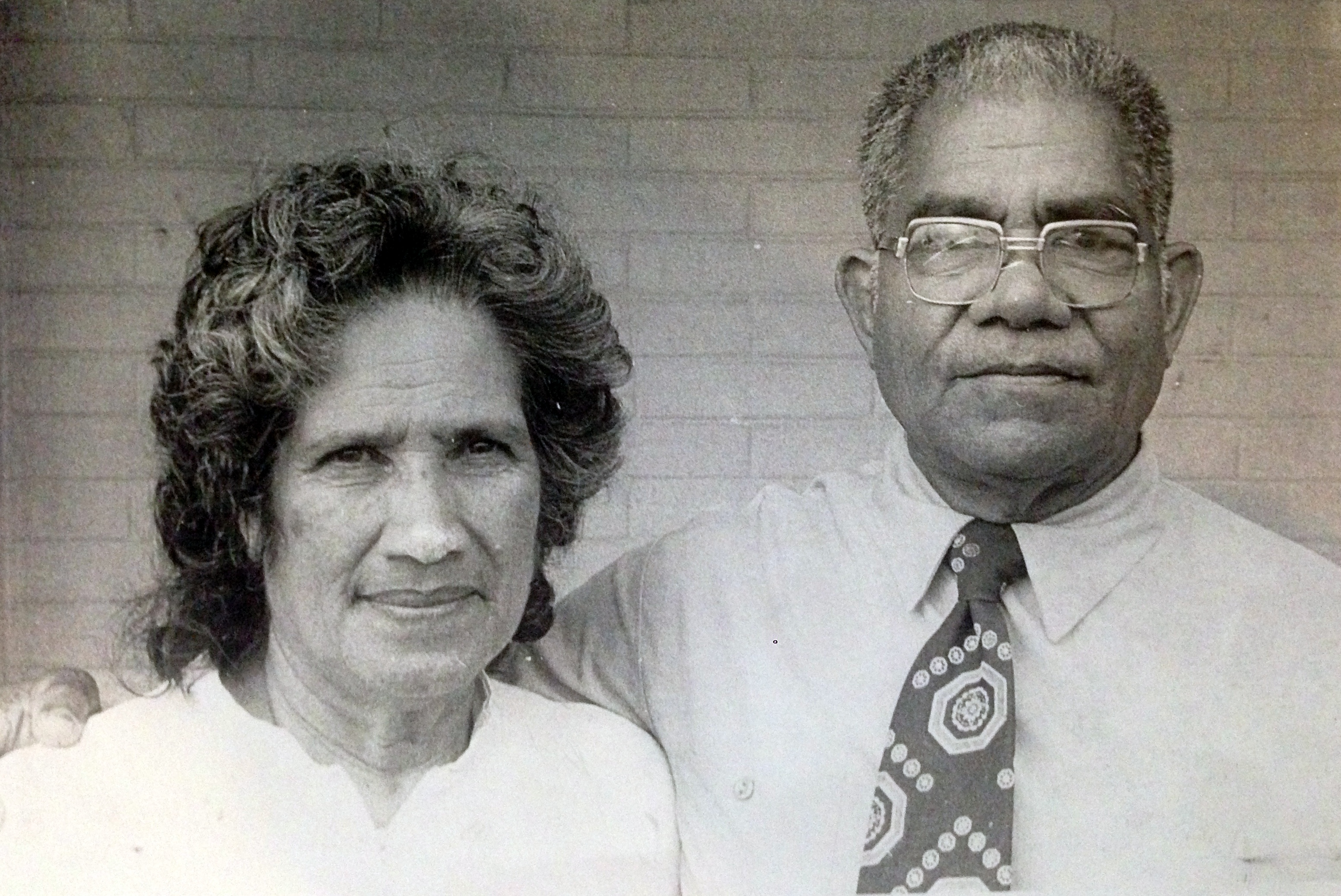

The Romes were the first couple from Papua New Guinea to attend the temple

According to the Church’s online Directory of Organizations and Leaders (an extremely valuable resource that we will miss being able to access once we have to give up our status as full-time Church History specialists), Brother Rome, the first man from Papua New Guinea to attend the temple, was still alive and serving in the presidency of the PNG Port Moresby Mission. No personal contact information was listed, so Nancy sent an email message to the mission office asking to get in touch with Brother Rome. She was surprised and delighted to get a phone call from the mission president that very evening. He explained that Brother Rome lived some distance from Port Moresby in a village with neither phone service nor internet access, but that he would be coming to the city for a mission presidency meeting the next morning. “I will have him call you from my office, if that’s all right,” said the president. Nancy was pleased to get such a speedy response, but then began to worry about how to prepare for the next day’s call. What questions should she ask? Did Brother Rome even speak English, and if so, would she be able to understand his accent? Nancy wished she had the experience and equipment that Sister and Elder T had for recording oral histories, especially so she wouldn’t have to worry about writing everything down accurately during the call, but the audio recorder had been left behind at the office. Or had it?

Nancy rang Sister T. “Wendy, I have to do a phone interview tomorrow afternoon. You don’t happen to have an audio recorder at home, do you?” She did. At this point (May 2020), New Zealand’s COVID alert level had been taken down a notch, so we weren’t going to get fined if Wendy brought the recorder over and showed us how to connect it directly to the phone; we just had to stay two metres away from her during the demonstration. Wendy came over the next morning and gave Nancy some suggestions for conducting the interview along with help for setting up the equipment.

When the phone rang a while later, Nancy was ready. Brother Rome was very cordial and his English was not hard to understand, but best of all was that after Nancy reviewed the reason for her request and started asking questions, Brother Rome said, “I’d like to talk this over with my wife and get her input before I respond. Would you mind if I just wrote something down for you and sent it by email?”

“That would be great!” Nancy said, tremendously relieved that she wouldn’t have to transcribe anything from a voice recording. She reminded Brother Rome that he and his wife would need to fill out and sign the donor release form she had already emailed to the mission office, expressed gratitude for their willingness to help, and said goodbye.

A few weeks later, Nancy received an email from Brother Rome saying that he had written a couple of pages about the experience he and his wife had when they went to the New Zealand Temple, and that he had given the papers to his son-in-law to scan and send to her. “Thank you so much!” she wrote back. “I look forward to reading about your experience.” Then she waited. And waited. And waited. No more messages arrived. No file containing scanned papers. She wrote to Brother Rome again, asking for his son-in-law’s contact information to make sure he had sent the file to the right address, then sent a message to the son-in-law. No response. Another message to Brother Rome evoked an apology; the papers had been lost, but the family was looking for them. More weeks went by with no further word, then months.

By September 2020, all the other stories to be included in the exhibit had been chosen, written up, and edited, and the wall displays had been designed. From the Church News archive, we had obtained a photo of Brother and Sister Rome taken at the Visitors Centre in Hamilton when they came to the temple in 1984, but we had no story to fill the blank space next to it. The deadline for submitting all exhibit text to the Church’s Publishing Services Department for final processing was approaching, and Nancy still had not received anything more from Brother Rome. The project manager in Salt Lake suggested that maybe we’d better choose another story, but Nancy wasn’t ready to give up on the Romes. Besides, she’d been praying and even fasting about the matter, and had faith that the Romes’ story would eventually land in her inbox.

Two days before the submission deadline, the file arrived. Brother Rome had handwritten his story on the back of the donor agreement form the mission president had printed for him, and it was beautiful. The Romes had been contacted by Latter-day Saint missionaries, accepted their message, and joined the Church in 1983, and the following year, the president of the Australia Brisbane Mission (which had jurisdiction over Papua New Guinea at the time) offered the Romes the opportunity to travel to the New Zealand Temple to be sealed as a couple for eternity. They were incredulous at first—could it be true?—then nearly overwhelmed with fear. Neither of them had ever traveled beyond their home district, let alone left Papua New Guinea in an airplane. When Nancy later contacted the former Brisbane Mission president, she learned that before their district president had invited them into his office to take the call from the mission president, the Romes had never used a telephone. Until the senior missionary couple assigned to help them prepare for the trip bought them each a sweater and a pair of shoes, they had never worn such things. “We were terrified,” Brother Rome admitted, but they wanted to enjoy the blessings of the temple and taking a huge leap into the unknown was the only way to do it. “Prayer and fasting calmed our fears,” said Brother Rome. Sister Rome added that it was worth the anxiety. “When I went inside the temple, I knew it was the House of the Lord.” The spirit they felt there and the knowledge they gained strengthened their faith and helped them become some of Papua New Guinea’s most stalwart Church leaders.

It was uncovering stories like this one that made our research so rewarding. Every now and then, after we were able to return to the office, Eva would call out, “Oh! You’ve got to come see this!” and everyone would gather around her monitor to watch the inspiring video she had just found. Or Nancy would share a story she had composed from primary sources, including extra details and background material that would have to be cut from the final version because there just wasn’t enough room on the walls for everything.

Structure

The three thematic sections of the Sacrifice and Consecration exhibit are titled The Call, The Construction Camp, and The Continued Commitment. The Call comprises accounts of how people came to serve on The Project. While many received a formal mission call from Church leaders, many did not. Some were sent by their parents. Others came because their friends or cousins were participating and didn’t want to be left out. At least one young man, not a Latter-day Saint, was brought to The Project by the Hamilton police. The wife of the temple’s construction supervisor later reported, “They thought that we could do something with him. He was always drunk. Now he is a wonderful boy” (Vernice Gold Rosenvall, The New Zealand Years 1955-1961, unpublished journal, p. 76). Many more said they felt inexplicably drawn to The Project and simply showed up to work.

Daphne with Nancy at the exhibit opening

Jock and Daphne were in the latter category. In 1956, as new members of The Church of Jesus Christ, they were invited by the missionaries to travel from their home in the South Island to the hui tau being held at the site of the partially completed college. They had such a marvelous experience among the Latter-day Saints gathered there that they didn’t want to leave, so as soon as they returned to Invercargill, they sold everything they could, loaded their three small children into a truck, and drove back to Hamilton. When they arrived at the construction site, they went straight to the personnel office and said, “We’re here to work as labor missionaries.” The personnel manager had no idea they were coming and wasn’t sure what to do with them, so he sent them to Elder B, The Project’s construction supervisor. Assuming the newcomers were as unskilled as most volunteers who arrived unexpectedly, Elder B turned them away, explaining that he had no need for more workers nor accommodations for another family on the site. As the disappointed couple turned to walk away, the supervisor suddenly felt prompted to ask, “What do you do?” Jock responded that he was a plumber.

Elder B’s whole demeanor changed. “Oh, then we do need you,” he said. “We have been praying for plumbers!” Jock was put to work immediately and the family moved into one of the bunkhouses, living with several single men for two months until a more private bach became available. “The children absolutely loved it!” Daphne reported later, and she did, too. Nurtured by people with longer experience in the Church and strong testimonies of Jesus Christ, Daphne and Jock built lifelong friendships and a solid foundation of faith.

Farm crew

The Call also includes stories of people who did not come to work as labor missionaries themselves, but who faithfully responded to the call to support those who did. Church members in districts across New Zealand reserved sections of their gardens and farm fields for The Project, sending the produce to Hamilton as often as they could. Often, the men who drove the delivery trucks from outlying areas would stay an extra day to help with construction. So many districts sent donations of livestock that the Church soon had to create paddocks on a portion of the Tuhikaramea land, designate a farm manager, and establish a dairy and slaughterhouse. Saints in the South Island sheared sheep and held bake sales to raise money to support the labor missionaries. One camp resident expressed tremendous gratitude when she opened a box sent by Church members in Dunedin and discovered that it was filled with gumboots, true treasures for men who often had to work in knee-deep mud.

Camp residents endured frequent flooding

The Construction Camp, the exhibit’s second section, describes the joys and challenges shared by those living and working at The Project. Enduring common discomforts that included cramped living quarters, food shortages, and frequent flooding, camp residents developed a close-knit community in which people took care of each other—physically, emotionally, and spiritually. Gospel study classes were held each morning before breakfast for the workers, and later in the day for the mothers, after the children had been put on the school bus and some chores had been done. Single women and those with older children worked in the construction offices, kitchen, and sick bay; younger mothers looked after the preschoolers and helped with food distribution, laundry, and sewing.

Saturday night dances held in the Kai Hall

Initially, the single young men working on The Project wanted to go into town to amuse themselves during their hours off, but Elder B was wary of what might happen if they went to dance halls and other places where alcohol was served. To keep his crew both happy and safe, he began holding well-supervised dances at the camp. To ensure the boys would have enough dance partners, he sent someone from the transport crew into Hamilton to pick up a busload of off-duty single female nurses from the hospital. As the years went on and the camp population grew, recreational activities and entertainment evenings featuring homegrown talent were added to the regular schedule. These included rugby, basketball, and other sports; singalongs, choral and jazz band concerts; and cultural performances such as kapa haka and Polynesian dancing. Camp residents who played and practiced together in addition to working side by side developed strong bonds of friendship and love. For the labor missionaries and their families who had truly consecrated their lives to the Lord’s service, the camp became like the Christian communities described in scripture, where “the multitude of them that believed were of one heart and one soul” and “had all things in common” (Acts 4:32).

Saints from Tonga deplaning in Auckland

Fijian Saints on their way to the airport

The third section of the Sacrifice and Consecration exhibit illustrates The Continued Commitment of laborers who went to great lengths to ensure that the temple would be finished on schedule. Because President McKay and his entourage and many Latter-day Saints from other parts of the South Pacific had already booked long-distance travel to attend the temple dedication, it was crucial for the building to be completed by the end of March 1958. Crews worked around the clock during the last weeks of summer, plastering, painting, and landscaping. Relief Society sisters not only provided the working men with an extra meal every night at 9 or 10 p.m., but also labored long hours themselves, polishing the bronze oxen at the base of the baptismal font, hanging curtains, and sewing the special clothing that would be used in temple ceremonies. Immediately following the dedication, instead of going home to rest, many of the same people donned their new white temple clothing and began running all-night endowment and sealing sessions to accommodate Saints from Tonga and Samoa whose return flights were leaving the next day. The visitors, most of whom had scrimped and saved for years to make this once-in-a-lifetime trip, hadn’t realized that the temple wasn’t scheduled to open for ordinances until at least a week after the dedication, so the unselfish labor missionaries who had been called to serve as ordinance workers made sure their guests did not leave disappointed.

Lu’isa and Viliami Kongaika sold everything they owned so they could take their whole family to the temple

The Kongaikas were typical of Saints from other Pacific islands who wanted to come to the temple. When this Tongan family learned that a temple was being built in New Zealand, Brother and Sister Kongaika were determined to take their six children there with them to be sealed for eternity, but travel was costly and their income meager. The only way they could afford the trip was to sell everything they owned—so they sold it, including the house Brother Kongaika’s father had built. Everyone else on their tiny island derided them as foolish, but as Brother Kongaika explained to his son, “We may not have anything now, but we’re building a mansion in heaven for our family.” After their return to Tonga, Brother Kongaika was offered a job as a security guard at a Church school, and the family moved into the guardsman’s quarters on the property. Three years later, a hurricane ravaged the island where the Kongaikas had lived previously, destroying the house they had sold along with those of their former neighbors. “So we never really lost anything,” Brother Kongaika concluded. His son recognized that they had “been blessed because our parents were committed to building an eternal family.” (Sources: Islands of Love, People of Faith, produced by Thomas A. Griffiths, 1992; ‘Isileli T. Kongaika, “Sacrifices Are Necessary for Creating an Eternal Family: Our Family Temple Story,” letter to Joseph Cottle, 20 September 2009, https://www.familysearch.org/tree/person/memories/LRZ1-KYY.)

Tiffany had found a reference to the Kongaikas’ story in a 1992 Church News article about a video on the history of the Church in the South Pacific, but she couldn’t find the video anywhere in the Church History archives. Nancy, however, quickly located it on YouTube (“I never thought of looking there!” Tiffany exclaimed). It had been shown on BYUTV but was privately produced, so Nancy contacted an old friend who worked for BYUTV to determine whether we could secure the rights to show the segment about the Kongaikas as part of our museum exhibit. It turned out that the production company was no longer in business and no copyright owner could be located, so the legal department gave us permission to use the video clip. (Since then we have learned that the old video is no longer available on YouTube because it has been acquired by Living Scriptures Streaming, so we were blessed to have found it when we did—for free!)

(to be continued)

This is a wonderful, inspiring story! I look forward to the next installment. Good to hear from you. too. This could be a book, or a long-form story for BYU Studies, or a shorter-form story for the Liahona–your blog is such a precious resource; you should at least create a book of it for your children (and friends).

Beautiful reading, loved reading the history. Brought back a lot of lovely memories.

An uncle Buck Ruruku who was one of the early labour missionaries would bring many of the missionaries home to D’Urville Island for the

Christmas holidays. Our father would meet the Wellington to Nelson ferry at midnight to pick them up.

Many of the Australian saints were here and have beautiful stories of faith.

Thank you Nancy and Michael Harward for the wonderful work you do.

Thank you so much for sharing!