The breakfast buffet at the Holiday Inn was busy, even though we got there by 7:30 am. It wasn’t the type of crowd one would have expected at an airport hotel. Rather than waiting for a turn at the coffee/hot chocolate dispenser behind people in business attire, we were competing with a lot of Disney-clad kids and grown women sporting glittery Minnie Mouse ears. Charles de Gaulle Airport is only a ten-minute train ride away from Disneyland Paris, and on this morning the Holiday Inn Roissy seemed to be hosting a lot of families—mostly southeast Asians—on their way to the Magic Kingdom. (By the way, although most Americans persist in calling Disneyland Paris “EuroDisney,” the “Euro” was dropped more than twenty years ago after Disney’s marketing research department determined that Europeans were turned off by the term, associating it with business and finance rather than fun.) Nancy was excited to find chunky applesauce as well as high-quality croissants at the buffet, and a whole counter laid with sliced deli meats and cheeses allowed us to stash sandwich fillers away in the plastic bags we had brought just for that purpose so we would have something to eat on the train later in the day.

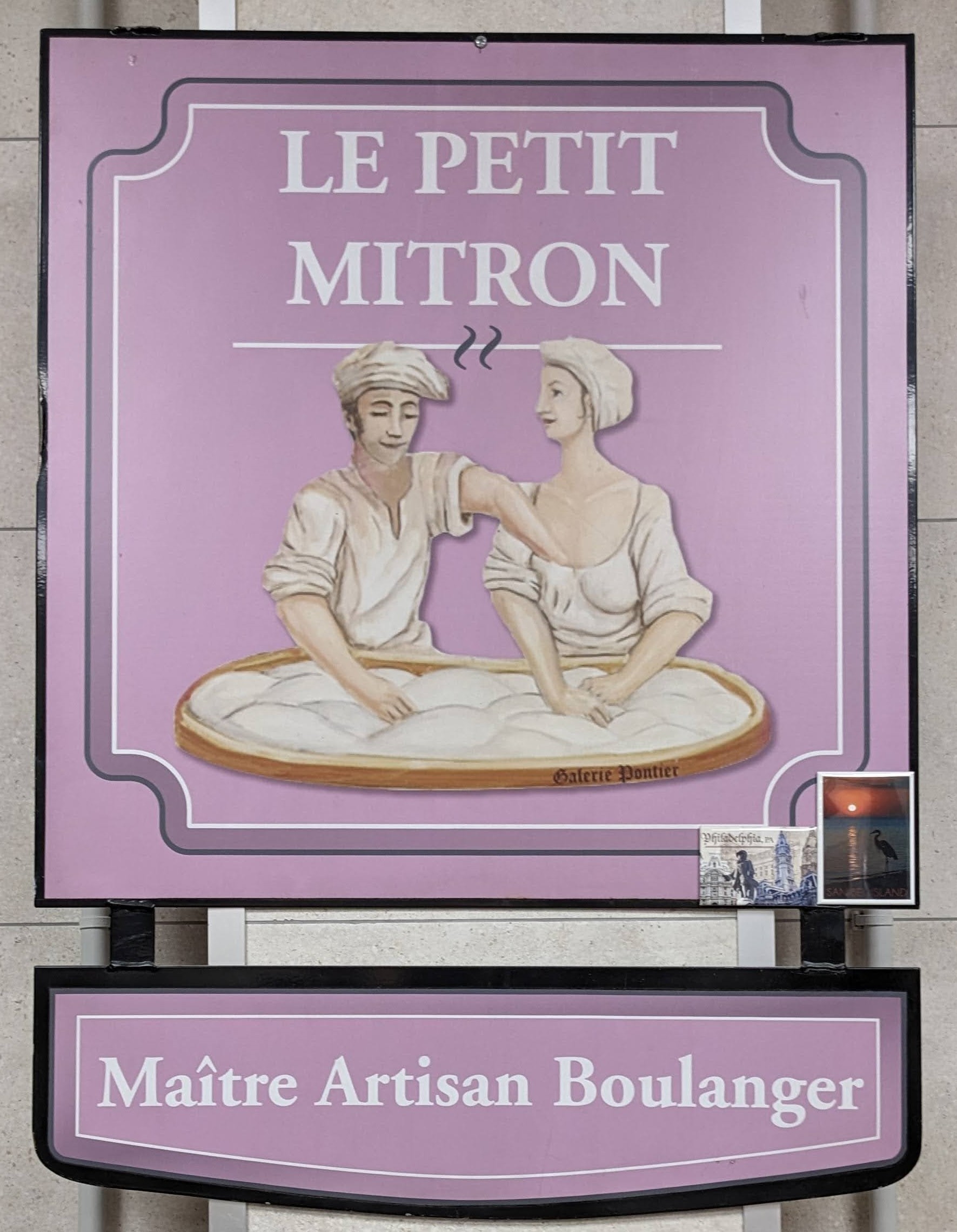

By 8:00 a.m. we were on our way back to the SNCP station at CDG, where we used our hard-won Navigo cards to board the RER bound for Gare du Nord. After nearly an hour on that train, we switched to the Metro for a 15-minute ride to the Oberkampf station in the Eleventh arrondissement. Our destination was Le Petit Mitron (The Little Baker Boy), where maître artisan boulanger (master artisan breadmaker) Didier L—- was offering a class in breadmaking.

Michael and Pat outside the boulangerie

An employee works the retail shop

We arrived at the boulangerie about half an hour before the class was scheduled to begin. Pat’s heart was galloping after climbing several flights of stairs in the Metro, so while she sat down inside the bakery to rest, Michael and Nancy took off to see if we could find the building where Michael had lived for a couple of months as a young missionary, also in the Eleventh arrondissement. Nancy knew the place because the second floor of the building had served as the meetinghouse for the Paris Ward, which we had attended several times with our BYU Study Abroad group in 1978. However, neither of us could remember the address or the exact location of the building, so our search was in vain. We’re not sure whether it was because the neighborhood has changed over the past four decades, or whether our memories just aren’t what they used to be.

An assistant baker sprinkles almond slivers on lemon-filled croissants

We were surprised to realize that the breadmaking class would be held right in the “operating room” of a very busy boulangerie, with Didier’s assistant bakers and sales staff bustling around us, very much occupied with their regular daily tasks. They seemed accustomed to the situation, however, and no one ever made us feel like we were in the way, and in fact were very friendly to their apprentices du jour. (The class is offered five days a week, but we seriously doubt that it would take place at all if it had to be approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration. No hair nets. No gloves. No masks.) In addition to the three of us, our training cohort included a French-speaking couple from California and their three daughters, ages 7, 10, and 13. We were joined by an Asian woman who was supposed to be providing English translation, but her heavily accented English was often more difficult for us to understand than Didier’s French.

Didier grinds his own flour (right bucket) and discards the bran (left bucket)

From the moment le maître boulanger began his instruction, we could tell that we were in for a marvelous morning. Didier’s passion for his vocation was obvious as he began explaining that, unlike most other Parisian bakers, he grinds all his own flour right there in his shop, and then proceeded to show us how to operate his commercial-size mill. We were surprised to learn that even though he takes pride in making a nutritious product, he never makes whole wheat bread. Indeed, after the outer bran layer is stripped off the wheat kernels, he actually discards it, claiming that bran is harmful to the body because that’s where most of the pesticides end up. (As someone who eats a bowl of bran flakes nearly every day—when fresh croissants are not available—Nancy was mildly alarmed to hear Didier state that bran is unhealthy and watch him throw used paper towels and other rubbish into the bag where the bran was collected—but not alarmed enough to eliminate bran flakes and whole wheat bread from her diet.)

Didier uses a commercial VMI mixer to blend his ingredients

How to tell when the dough has reached the right consistency

“De la farine, de l’eau, du sel, et de la levure—c’est tout!” said Didier (flour, water, salt, and yeast—that’s all!). He measured the ingredients into a VMI mixer and set it going, blending them into a smooth dough. After several minutes (during which we had a break to get a drink of water or use the toilet), Didier pulled the lump of dough from the mixer and asked us to touch it, really paying attention to how it felt. “How do you know when the dough has reached the right consistency?” he asked. To answer his own question, he initially told us that “it should feel like a baby’s bottom”; but a moment later, behind the backs of the young girls, he pointed to a plaque on the wall, winking. It showed the logo of the boulangerie, which depicts a pair of bakers, male and female, helping each other to knead a large quantity of dough. The male baker is testing its consistency by reaching into the female baker’s bosom to compare the one’s smoothness and elasticity to the other’s. (Kids: don’t try this at home!)

Risen mounds of dough ready to be shaped

Pat and Michael shaped their baguettes

Yet another surprise for us was learning that Didier does not accelerate the rising process by leaving the dough in a warm place. Instead, once he divides it into little mounds (about 350 grams/12 ounces each), he refrigerates the dough for at least 24 hours. At that point, it is ready to be shaped. For baguettes, each mound of dough is flattened slightly with a rolling pin, but only enough so that it can be folded back over on top of itself. It is then gently hand-rolled to form a 20-inch “baton.”

Learning to braid from the middle out

Shaped baguettes are placed on a lightly floured canvas sheet

For a braided loaf, the baton is cut into three long ropes, and then braided starting from the middle—a pro tip from Didier that prevents the braid from thinning too much at one end as the dough stretches. The ends are pinched together lightly to keep the loaf from coming apart. The formed loaf is then transferred to a metal baking tray covered with lightly floured heavy canvas.

Didier scores the remaining baguettes

Shallow slashes may be cut across the top of an unbaked baguette with a very sharp knife to create a distinct design as the bread bakes. Widely spaced diagonal slashes are traditional for baguettes, but Didier showed us how to score the dough differently to create more imaginative designs. Michael received the baker’s approbation when he scored his baguette with a single long serpentine slash from one end to the other. When Didier wants to make boules (round loaves) instead of baguettes, he either coils a long rope of dough into a small wicker basket, or just plops a round lump of dough inside and lets the basket impress its own design.

Deep cuts with sharp scissors and a series of twists transform a plain baguette into a leafy laurel branch

Didier creates a baguette shaped like an alligator

The bread is ready to bake at this point; there is no final rising period. The oven is preheated to 205°C/400°F. Of course, French boulangeries utilize special steam-injection ovens to produce the unique combination of crisp crust and light, moist interior that distinguishes a good baguette, but Didier assured us that it was possible to get good results with a standard home oven. To mimic the injected steam, he advised us to place a shallow metal pan in the oven while it preheats. Once the oven and the pan are hot, place the bread alongside the hot pan and immediately pour a cup of cold water into it, then quickly shut the oven door. (He advised wearing a long oven mitt to avoid getting a steam burn.) Unbaked baguettes weighing about 350 grams should be done in 20 minutes.

The baguettes in the oven

While the baguettes we had formed were baking, Didier began explaining how to make the rich, buttery pastry dough used for croissants and pain au chocolat. In the process, he let us in on a secret: French bakeries are legally allowed to produce two kinds of croissants: croissants ordinaires and croissants de beurre. “Ordinary” croissants may be made either in whole or in part with margarine or vegetable shortening (gah!) in place of butter, whereas croissants de beurre contain only the finest sweet cream butter. (This solved the mystery of why some of the croissants we’ve been served in France fell way below our expectations.) So how can you tell the difference when you are choosing from a boulangerie display case or a breakfast buffet? Didier explained that croissants ordinaires are the ones actually shaped like crescents; if you want one made with all butter, choose one that was rolled up straight, with no curve. Didier also shared the history of the croissant (no doubt apocryphal, but fascinating nonetheless). According to legend, European bakers began curling their sweet rolls into crescents, the symbol of the Ottoman Empire, after the forces of the Holy Roman Empire successfully expelled the Ottomans from Buda and Vienna in the 1680s. (Customers could then symbolically devour the enemy.) What Didier did not tell us was that those crescent-shaped sweet rolls originated not in France, but in Eastern Europe, where they are called kifli in Hungary, Kipferl in Austria, Hörnchen in Germany, and rugelach wherever Yiddish is spoken.

The Ottoman army surrounds Vienna in the 1683 battle that may have inspired the first croissants. Notice the crescent moon on the pennant flying over the Ottoman tent. (Painting by Frans Geffels)

In one version of the story, it was Viennese bakers, working in the cellars where their ovens were located, who first realized that Ottoman soldiers were digging tunnels under the city walls, and sounded the alarm that headed off the invasion. Although they may not have invented the crescent roll, the French are responsible for turning the denser, breadier Eastern European version into the unsweetened flaky pastry we know as a croissant. This origin story may also explain why flaky pastries stuffed with chocolate bars are called pains au chocolat (chocolate bread) rather than croissants au chocolat; the first versions probably were chocolate-filled sweet rolls.

The butter professionals use contains up to 87% butterfat. Butter sold in French grocery stores usually contains 82%. In the U.S, it’s only 80%

But enough history. How are those delightfully flaky croissants de beurre made? Didier explained that pastry dough starts with the same dry ingredients as for bread: flour, salt, and yeast, but instead of water, the mixture is moistened with milk and eggs.

Slabs of chilled butter are pounded flat before they are wrapped inside the pastry dough

Didier explains how the rolled out dough is used to create an envelope for the butter

The envelope is pressed using a commercial grade pasta machine

Chocolate bars are rolled inside pastry dough to create pains au chocolat

The process is the same for mixing and chilling the dough, but the big difference comes when the dough is rolled out: a dough rectangle rolled about 1 centimeter thick is wrapped around a big slab of chilled butter, refrigerated for several hours, and then the resulting “envelope” is sent through a pasta machine, which laminates the butter within the dough. And it’s not just any butter; Didier told us that the best pastries are made with baker’s butter, which has a higher fat content than the butter sold in grocery stores and thus stays firm longer. The process is repeated with another slab of butter—and then another, and then another, until two kilos of butter have been incorporated into two kilos of dough, layer upon layer. After a final chilling, the fully laminated dough is put through the pasta machine one more time, cut into squares, then cut again on the diagonal to form triangles which are then rolled up—but not curved into crescents, because Le Petit Mitron does not make croissants ordinaires. The rolled pastries are then chilled again before baking.

Next, Didier let us try our hand at rolling up some pains au chocolat, made with the same pastry dough as the croissants. We added finger-size bars of dark chocolate—three in each roll. Didier told us that most other Parisian bakers put only two bars in their pains au chocolat, so of course, his are superior.

Didier, Nancy, Pat and Michael

By this time, our baguettes had come out of the oven. An assistant sliced some up so we could sample the finished product. Ooh la la! C’est magnifique!

Unfortunately, time did not allow us to sample one of our own pains au chocolat, but we did get to taste some that had been made earlier. And before we left, Didier gave us the remaining bread that we had rolled and shaped ourselves. Our party of three came away with five full baguettes, not quite sure whether we would be able to finish them before they went stale.

The class had gone longer than anticipated, so we had to leave tout suite (right away). We had an appointment to attend the 2:45 p.m. session at the Paris Temple of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, located just outside Versailles. A quick consultation of the Bonjour RATP app Michael had downloaded told us which direction to go and even how long a walk we could expect, first to reach the Metro station to reach the temple at the other end of the suburban line. Time was short, but fortunately, there was a direct Metro to Gare Saint-Lazare, where we caught a suburban train to Versailles Rive Droite (which uninitiated temple-going tourists often confuse with Versailles Rive Gauche, which is closer to the palace than to the temple).

Michael and Pat relaxing and mentally resetting on the train

Once on the train, we could relax, eat the sandwiches we had prepared earlier (and more fresh bread), and change our frame of mind so we would be ready to attend the temple. As we approached Versailles, Michael put on a tie and Nancy and Pat exchanged the pants they had been wearing for skirts as a show of reverence for visiting the House of the Lord.

Versailles Rive Droite train station

We hired a taxi to take us the last mile to the temple

Arriving at Versailles Rive Droite about 2:20 p.m., we decided to hire a taxi instead of walking from the train station to make sure we would not be late for the temple session. We didn’t have to give the driver an address; as soon as Michael mentioned the temple, he knew exactly where to go.

Technically, the temple is not in Versailles, but a few kilometers north in Le Chesnay-Rocquencourt. Back in 2015, when the LDS Church announced its intention to build a temple in France, Gérald Caussé was serving in the Presiding Bishopric of the Church, and within months was ordained Presiding Bishop. As such, he was intimately involved in the project of building the first temple in his homeland. Anticipating some opposition when he met with local government leaders to discuss the Church’s proposal, he prepared a detailed and thorough presentation in the hope of obtaining permission to proceed. However, at the meeting, the officials told Bishop Caussé they were not interested in his presentation, preferring to conduct their own research.

Local officials were impressed that the Church would place a copy of Bertel Thorvaldsen’s Christus in the temple grounds. A crane had to be used because the space is completely enclosed by buildings

When their decision was announced, to everyone’s surprise and delight, the government made no objection to the temple project. Their research had determined that The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints not only professed to be Christian, but demonstrated its commitment to Christian principles more than any other organization they had investigated.

Beautiful stained glass of Christ in the Visitors Center

An endowment session at a Latter-day Saint temple is something like a Catholic Mass in that both utilize a set liturgy, but although both outline basic Christian tenets and invite participants to praise the Father, the Son, and the Holy Ghost, that’s where the similarity ends. During the sacred endowment ceremony, Latter-day Saint temple-goers also commit to following Jesus Christ by living lives of obedience, sacrifice, chastity, and service.

Entrance to the temple

When we arrived at the temple, we were greeted as warmly as at any other temple we’ve attended, and were shown where to go in the unfamiliar building. Although we knew that we could listen to the proceedings and respond in English (translations in about a hundred languages are available at every temple around the world), Michael and Nancy chose to participate entirely in French—not too much of a problem for Michael, but something of a challenge for Nancy when she needed to give verbal responses. She did pretty well, with a little assistance from a temple worker wearing a name tag that said: Angélique D—-. Nancy recalled that D—– was the surname of one of Michael’s French missionary companions, so after the session ended, we found Angélique and learned that she was Elder Charles D—–’s sister. She and Michael were able to spend a few moments sharing tender memories about Charles, who had passed away from cancer a couple of years ago. During the seven weeks they had served together as missionaries, Michael blessed Elder D—– by ensuring that he was able to get to Switzerland to attend the temple for the first time (Bern having the only temple in continental Europe in 1975); Elder D—– had in turn blessed Michael by ensuring that he learned to communicate entirely in French—a real boon to his remaining time as a missionary, not to mention a boon to our collective ability to enjoy subsequent visits to France.

Flowers on LDS temple grounds are always in bloom

We took some time after the session to admire the flowers on the temple grounds and find the adjacent workers’ lounge, where we left the baguettes we had not been able to finish for others to enjoy. Then we went into the Visitors Center so Nancy and Pat could change back into more casual clothes. While they were changing, Michael spotted Pierre and Josie L—–, a couple he had met during his mission, and with whom both of us had become better acquainted during the six months we spent in Paris in 1978. Later, when we brought our children to France to celebrate Christmas 1993 with their French cousins in La Rochelle, we also spent a day in Paris with Pierre and Josie and their family. In addition, Pierre and Josie had hosted our daughter Hillary and her companions when they visited Paris about twenty years ago, so we’ve maintained cordial relations over the years and were thrilled to encounter each other again at the temple.

Not long after retiring from his career as a physician, Pierre was called to serve as a counselor to the first president of the Paris Temple and Josie was called as an assistant temple matron, so they sold their home on the other side of the city and moved to an apartment in Le Chesnay. Although they were released from their leadership duties a few years ago, they continue to serve as part-time temple workers.

Michael with Josie and Pierre

After Nancy and Pat had come out of the women’s room and Pat had been introduced to our French friends, Josie asked, “Do you have plans for the evening?” When we replied that we had planned only to return to the city and then go out for dinner somewhere, she and Pierre invited us to come home with them for the rest of the afternoon, and then we could go out to dinner together. This sounded like a wonderful plan! Pat was excited for the opportunity to visit another “real French” home—and was relieved that both Josie and Pierre could speak English. Josie had worked as a translator for the Church, so her English is excellent. The couple led the way to their car in the parking garage under the Visitors Center (where we were pleased to see several charging stations for electric vehicles. Can we please get some of these at our temple in Columbus?). Although their apartment was only a short drive away from the temple, Pierre elongated the trip to give us a brief tour of the city of Versailles, including a view of the famous palace. Although not nearly as large nor as opulent as the home of Louis XIV and his heirs, Pierre and Josie’s apartment was nicely decorated and very comfortable. They said that they didn’t miss their larger home and were happy to have made the move to Le Chesnay, where a variety of stores and services meet almost all their needs. And even though none of their children live in the vicinity, they still come to visit regularly—especially because the temple is nearby.

Walking to the restaurant

Le Touareg

We were brought up-to-date on the L—- children and grandchildren by flipping through family photo albums until it was time to head for the restaurant. Earlier, when Josie had asked what type of cuisine we were in the mood for, we had a ready answer: Moroccan. Pat had spent a few years as a young girl living in Port Lyautey (now called Kinitra, about 55 kilometers/35 miles northeast of Rabat) while her father was assigned to the US Naval Air Station there. (This was before Michael was born.) She had vivid memories of the couscous their Moroccan cook frequently prepared, and hoped to experience that taste from her childhood again. We knew she could find some authentic Moroccan food in Paris, where many people of North African descent now reside, and had promised her a couscous dinner on her last night in France. Josie said, “I know just the place,” and made reservations at Le Touareg, a restaurant named for the nomadic Berber tribe that inhabits the Sahara. The restaurant was not far from the apartment; indeed, it was close enough for us to walk—which we did.

Michael’s delicious grilled lamb and couscous

Despite the fact that Pat was eager to eat couscous, she wasn’t eager to eat lamb—another item that often appears at Moroccan meals, but one that Pat doesn’t remember with as much fondness. She was relieved to see that Le Touareg’s menu included a chicken option to go along with the couscous. However, when her order arrived and she took a bite of the couscous, we were shocked to hear her exclaim, “They’ve ruined it!” Apparently, this couscous—cooked with onions, tomatoes, and various spices—bore little resemblance to the plain, unseasoned granules of steamed semolina she remembered from her childhood. She was happier after Pierre asked the server to bring her a bowl prepared without the extra ingredients. In contrast, Nancy didn’t think the couscous with braised lamb shank she ordered was spicy enough, but she fixed it by adding a couple of spoonfuls from the bowl of harissa already on the table. Michael seemed to have made the best choice by ordering grilled lamb, which was very flavorful all on its own. In addition to the meat and grain, we got bowls of zucchini, carrots, potatoes, and garbanzos in broth (which also benefited from the addition of a little harissa), and a plate of very good olives and potatoes dressed with olive oil and paprika.

Dessert? Of course—especially after Pat learned that the choices included chocolate mousse. Alas, she was nearly as disappointed with her first taste of mousse as she had been with the couscous. The chocolate was too dark for her palate, but the problem was easily remedied with a side order of whipped cream. Michael, on the other hand, loved the extra-dark chocolate. Nancy probably would have landed somewhere in between had she ordered the mousse—but she hadn’t, opting instead for a scoop of Mövenpick passion fruit-mango sorbet.

Pat and Nancy waiting for our train back to the hotel

Versailles Chantiers train station

Unfortunately, the service at Le Touareg had been slow (though no more so than at many restaurants in France where the clientele includes more locals than tourists), so it was after 9 p.m. when we left the restaurant. We still had to walk back to the garage where Pierre and Josie’s car was parked before they could drive us to the train station. They took the train into Paris often enough to be familiar with transit schedules, so they dropped us off at the Versailles Chantiers station to begin reversing our day’s journey most expeditiously. Nevertheless, it was nearly 11:30 p.m. when we arrived back at the hotel and after midnight when we finally got to bed. We tried not to think about the fact that we needed to be packed and ready to leave for the airport at 8 a.m. the next day to begin our “Norway in a Nutshell” experience.

Norway in a nutshell – I can’t wait!