On the Monday after Easter, following our weekend of Māori immersion at Hui Tau 2021, the nine of us full-time Church History missionaries packed our clothing, equipment, and the remainder of our food into our two vans and left the Bayswater Holiday Home in Paihia behind. Elder T drove the mission van straight back to Hamilton, taking Rangi, Vic, and Elder E with him. Their assignment was to hold down the fort at the Matthew Cowley Pacific Church History Centre for the next couple of days while Sister E (aka Jo-Ena) took the rest of us (Wendy, Diane, Nancy, and Michael) to see more of Northland in her van. Jo-Ena had grown up in Northland and was eager to introduce us to places she remembered from her childhood.

On the Monday after Easter, following our weekend of Māori immersion at Hui Tau 2021, the nine of us full-time Church History missionaries packed our clothing, equipment, and the remainder of our food into our two vans and left the Bayswater Holiday Home in Paihia behind. Elder T drove the mission van straight back to Hamilton, taking Rangi, Vic, and Elder E with him. Their assignment was to hold down the fort at the Matthew Cowley Pacific Church History Centre for the next couple of days while Sister E (aka Jo-Ena) took the rest of us (Wendy, Diane, Nancy, and Michael) to see more of Northland in her van. Jo-Ena had grown up in Northland and was eager to introduce us to places she remembered from her childhood.

Doubtless Bay

From Paihia, she drove us north to Kerikeri, then west along Route 10 toward Doubtless Bay and Rangaunu Harbour. At Awanui, where Route 10 meets National Highway 1 at the base of the Aupōuri Peninsula, we stopped for petrol and met Jeff and Kara, who had been following us in their own car. They left their Corolla at a community park and joined the rest of us in Jo-Ena’s van for the 100-km (62-mile) trip to Cape Reinga at the north end of Highway 1.

The Aupōuri Peninsula is a narrow spit of land with few residents and a lot of avocado and citrus orchards. Ninety-Mile Beach occupies the peninsula’s entire west side. The beach is actually only 55 miles long (the early European settlers who named it must have mismeasured), but it’s still one of the longest stretches of unbroken, flat, sandy coastline in the world. We’re told that it’s officially classified as a public highway and that one can indeed drive along it when the tide allows, but Jo-Ena wasn’t keen on trying that in a heavily loaded van (and neither were the rest of us).

Michael and Nancy with the confluence of the Tasman Sea and the Pacific Ocean

Nancy, Diane, Jo-Ena, Wendy, and Kara at Cape Reinga

Te Rerenga Wairua, where spirits of the dead leap into the underworld

Cape Reinga is often said to be the northernmost point of the North Island, but that distinction belongs to the Surville Cliffs, 30 km east of the cape, which are actually 3 km farther north. What drew us to the cape, however, was not so much our desire to reach New Zealand’s northernmost point (although we admit that it is rather satisfying to be able to say that we’ve driven to both the far north and far south ends of Highway 1) but also our desire to see the confluence of two oceans. The Tasman Sea and the Pacific Ocean meet under the watchful eye of the Cape Reinga lighthouse, and their meeting is not a peaceful one. The two seas, each with a different hue and moving in its own direction, visibly clash, roiling the water around the cape. In local Māori folklore, the stormy Tasman Sea, called Te Moana Tāpokopoko a Tāwhaki, is male, and the Pacific Ocean, called Te Tai o Whitireia, is female, and their turbulent union symbolizes the creation of life. Interestingly, this place representing the beginning of life also represents its end. According to Māori tradition, spirits of the dead gather on the cape’s promontory, known as Te Rerenga Wairua, to leap into Te Reinga, the underworld.

Our tailgate banquet in Jo-Ena’s van

Another van in the carpark at Cape Reinga had everything including the kitchen sink

We agreed that Te Rerenga Wairua would be a fine place to begin our own journey into immortality, but alas, the time for our leap into the unknown had not yet come. Instead, it was lunchtime. We hiked back to the carpark, where we made a fine meal of the leftovers Jo-Ena spread on the van’s tailgate.

While we were eating we were approached by a man with an American accent who said, “I have a question maybe you can help me with. I’ve heard that this weekend there was a holiday celebrating someone who supposedly rose from the dead. Was that today or yesterday? And what was that all about?” We suspected that he had noticed the name tags that identified us as representatives of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints and just wanted to mess with us a little, but we decided to answer as if his questions were sincere. We told him that Easter, a holiday commemorating the resurrection of Jesus Christ almost two thousand years ago, had actually been the day before, but was being legally observed that day. He thanked us for the information and then told us that he was a biologist from the U.S. who had come to New Zealand to study COVID, and that he had just recently been released from managed isolation. We weren’t sure whether to believe that part of his story any more than we believed that he needed to have Easter explained to him, but it was an interesting encounter nevertheless.

Homemade pies drew us to a roadside stand in Pukenui

On the way back to Awanui to retrieve the other car, we stopped at a roadside pie stand in Pukenui because Wendy had persuaded us that it sold the best meat pies in New Zealand. None of us was hungry yet, but we all decided to go ahead and buy some pies to save for dinner because we knew that on this Easter Monday only two restaurants would be open in Opononi, our destination for the evening, and neither had gotten great reviews on TripAdvisor.

Herekino Forest

When we arrived in Awanui we were relieved to find that Jeff and Kara’s vehicle had not been disturbed, and neither was anyone was particularly disturbed when Jeff and Michael announced that for the remainder of the afternoon the Corolla would become the “Guy Car” so the men could continue the conversation they had been having in the back of the van. Down the road about 9 km we left Route 1 and headed southwest on the Kaitaia Awaroa Road through the stunning scenery of the Herekino Forest. We wish we had had time to stop and hike a little, but because our aim was to reach Kohukohu in time to catch the 5:00 ferry across Hokianga Harbour, we couldn’t afford to even slow down.

Our vehicles in line for the Hokianga Ferry

Aboard the ferry

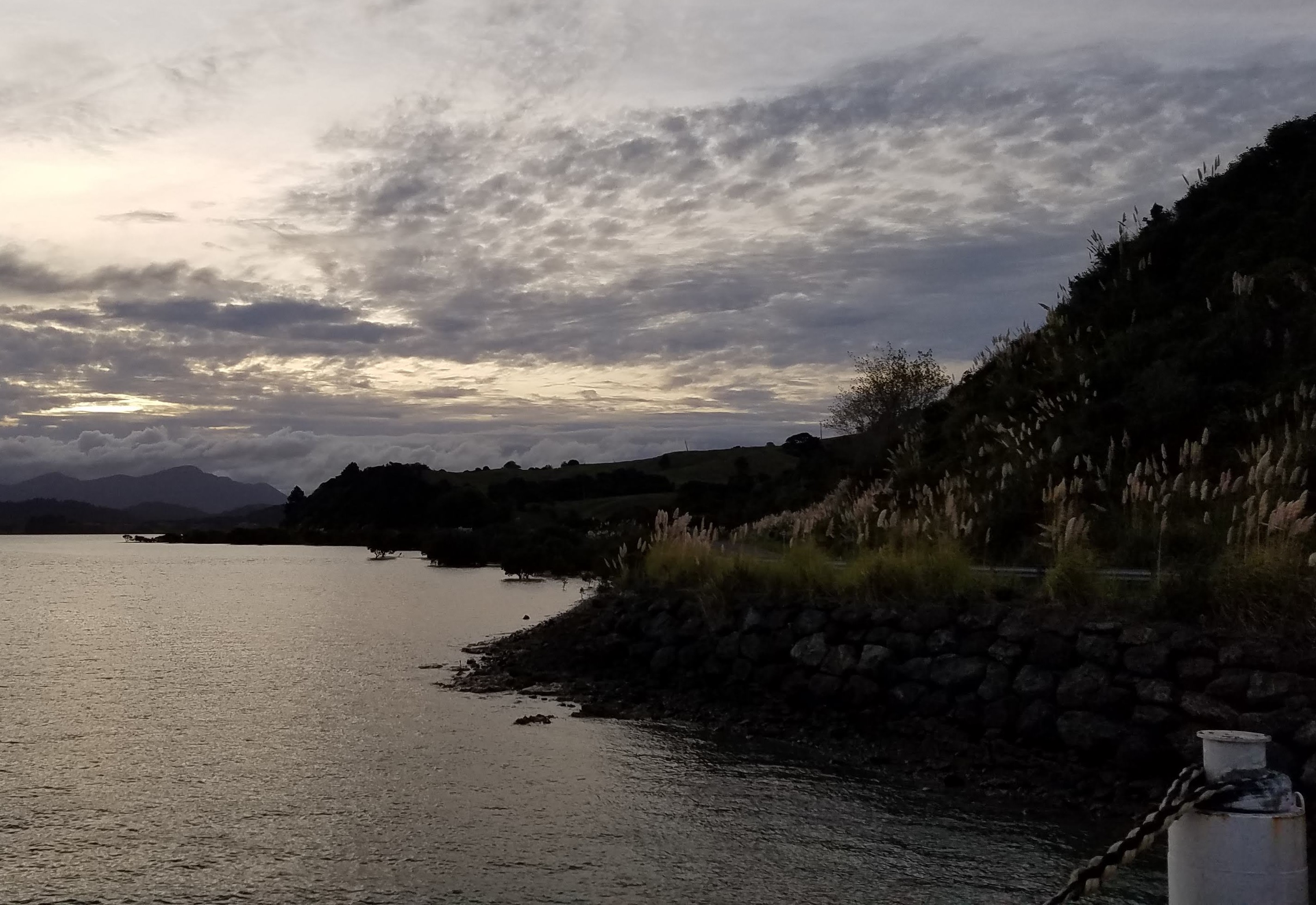

Hokianga Harbour at Kohukohu

We needn’t have hurried, because despite our rush we missed the 5:00 ferry and had to wait 45 minutes for the next one. Hokianga Harbour is a long, many-fingered estuary that extends about 30km inland to connect the Tasman Sea with the Mangamuka and Waipapa Rivers. Hokianga had been one of the first places settled by descendants of Kupe, the legendary Polynesian explorer who discovered Aotearoa, and during the nineteenth century the waterway became an important means of transporting logs from the area’s kauri forests to waiting ships.

While we waited for the ferry, we tried to calculate how much our fare would be, wondering whether or not the van would be charged the “large vehicle” rate of $30 NZD. We obviously didn’t qualify for the “locals” discount, which was significantly lower. When the agent came to collect the fare, he asked where we had come from and where we were going.

“We came from Paihia this morning, went up to the cape, and now we’re going to Opononi,” we told him.

“Oh, so you are locals,” he said, winking. “So that will be $18.”

Lighthouse Motel in Opononi

Half an hour later, we arrived at the Lighthouse Motel in Opononi, a small town at the mouth of the harbor. We were glad that we’d bought those meat pies and still had salad-makings in the chilly bin—and that our accommodations included well-equipped kitchenettes as well as two separate bedrooms in each unit. We took the dishes, kitchen chairs, and a small table from our unit next door to the suite that Jo-Ena, Diane, and Wendy were sharing so the seven of us could eat dinner together. We haven’t sampled enough meat pies around the country to determine whether the pepper steak and steak-and-mushroom ones from Pukenui were really New Zealand’s best, but they were very good indeed. On the other hand, Jo-Ena was not impressed with the paua filling in hers (“It must have been made from frozen,” she sniffed), but agreed that the pastry was “very nice.”

Kara samples some of Jeff’s meat pie

We had planned to play a game after dinner, but by the time we had sorted out our schedule for the next day, washed the dishes, and returned the furnishings to their proper places, we all admitted that we were too drained to stay up any longer. However, before we retired, Diane suggested that since the women had taken charge of preparing most of our meals over the weekend, the men should take a turn and make breakfast.

Michel et Geoffrey et le petit déjeuner

So mardi matin (Tuesday morning), “Geoffrey et Michel” (aka Jeff and Michael) became our chefs de cuisinette. The petit déjeuner they prepared from the ample supply of food left in Jo-Ena’s chilly-bins was not exactly petit: scrambled eggs, bacon, avocado toast, bran muffins, fruit, and juice. Both Jeff and Michael had served their first missions in France, so they brought some French flair to the whole presentation. The accents they assumed as they waited on the ladies may not have been authentic, but they were très amusants—and the meal, c’était magnifique!

Nancy in the Lighthouse Motel’s front garden

Michael chilling on the porch behind the motel

Because our first destination for the day was less than a kilometre from the motel and didn’t open until 9:30 a.m., we had time to either explore the neighborhood or just chill on the back porch before we needed to load the van and take off for Manea—Footprints of Kupe.

Michael checking out Manea’s interactive displays

Our guide

Papatūānuku (Mother Earth) and Ranginui (Father Sky) are represented in the lintel over the gateway into Manea’s sculpture garden

Manea is hard to describe. It’s not exactly a museum, but a Māori cultural and educational experience unlike any other we have been to. Sponsored by Ngāpuhi, Northland’s dominant iwi (tribe), it’s a new attraction, having opened only in December 2020, and we give the physical facility high marks for aesthetics. After paying admission (steep, but worth it) and passing through a gift shop offering tasteful merchandise, we walked across a courtyard to a large room filled with wall displays and a number of media stations. (As museum people, we made lots of mental notes about features we might suggest for incorporation into our own museum.) We had time to select a few short videos to watch before our guide announced that it was time for the live presentation to begin.

She then led our group (the seven of us missionaries, plus another couple) outside to a sculpture garden overlooking Hokianga Harbour. The various whakairo (wood carvings) along the footpath became illustrations as our young guide related the legends of Kupe, ancestor of the Ngāpuhi, and the supernatural beings who helped him navigate across the sea from Hawaiiki to Aotearoa.

Whakairo at Manea: Footprints of Kupe, representing Kupe’s supernatural guardians

- Tāne Mahuta, lord of the forest

- Tūmatauenga, god of war

- Tangaroa, god of seas, rivers, and lakes

- Rongo, god of peace

- Āraiteuru, guardian of Hokianga Harbour

- Tāwhirimātea, god of wind

Kupe’s companion, Ngahue, was captain of another waka on the voyage to Aotearoa

Warrior performing the wero

The guide displayed her kākahu (ceremonial cloak)

As she spoke, a young man appeared on a rise above us to perform the wero (challenge ritual), expertly brandishing his tao (spear). When we circled back toward the building, he and another young woman took over the presentation. The former blew a pūtātara (shell trumpet) to call us into the wharenui (meeting house), and the latter, wrapped in a beautiful kākahu (ceremonial cloak), chanted a karanga (welcome). They were quite surprised when we asked if we could sing a waiata (song) of our own, because even though such a response would have been natural for a group of Māori visitors, they didn’t expect it from a bunch of Americans. Our rendition of Rangi’s Kia Ngawari theme song was somewhat shaky because we didn’t have our cheat sheets to remind us of the words, but our hosts listened respectfully and seemed pleased that we wanted to honor their tradition.

Guides (and the figure of Kupe) welcome us into the wharenui

We passed through the foyer of the wharenui into a theatre where we watched a 4D film presentation telling more of the legend of Kupe, with the live guides participating in the storytelling. More of our senses were engaged when we felt wind and “sea mist” blown into our faces during scenes of Kupe’s ocean voyages, but the most unexpected of those sensory experiences came near the end, when Kupe’s nemesis, Muturangi, sent a giant octopus to try to thwart the hero’s progress. At that point, we felt rubbery straps lashing against our legs under the seats, with rather unsettling effect.

Manea’s sculpture garden overlooks Hokianga Harbour

Because there were few other visitors that morning, we had a chance to talk with the guides/performers for a while after the presentation. We learned that the young man was, like us, a Latter-day Saint and had participated in Hui Tau 2021; he had been one of the challengers at the powhiri (welcome ceremony) on Friday afternoon. The second young woman had attended Hui Tau, too, performing with Kaikohe’s kapa haka (line dance) group on Saturday afternoon. (For more about the Hui Tau experience, see our blogposts for 2-4 April). All three of the Manea guides/performers can trace their Ngāpuhi whakapapa (genealogy) back to Kupe himself. When we asked one of them if a copy of the script they used was available somewhere so that we could check it for correct names and other details of the narrative, we were surprised by her response. She said, “We don’t really have a script. Each of us tells the story a little differently, the way we learned it from our own whanau (family).” We should have realized that this would be the case because Māori have employed recitation and memorization to record and transmit their history for generations, and such traditions are being emphasized again after a century of official language and cultural suppression. And maybe these young Māori are not so different from many LDS kids we know who can retell stories from the Bible and the Book of Mormon just as fluently.

Ngāpuhi is New Zealand’s largest iwi and must be well-managed, because its leadership council has obviously put a lot of thought and resources into Manea—Footprints of Kupe. We were really impressed with the quality of both the presentation and the facility, and are happy for the opportunities it provides for the community. Northland has the lowest per capita income of all New Zealand’s regions, and sources of steady income are scarce, so we hope that this new venture will be as successful financially for the iwi as it was for us experientially. Really, Manea is worth a four-hour drive from Auckland even without the glorious scenery en route.

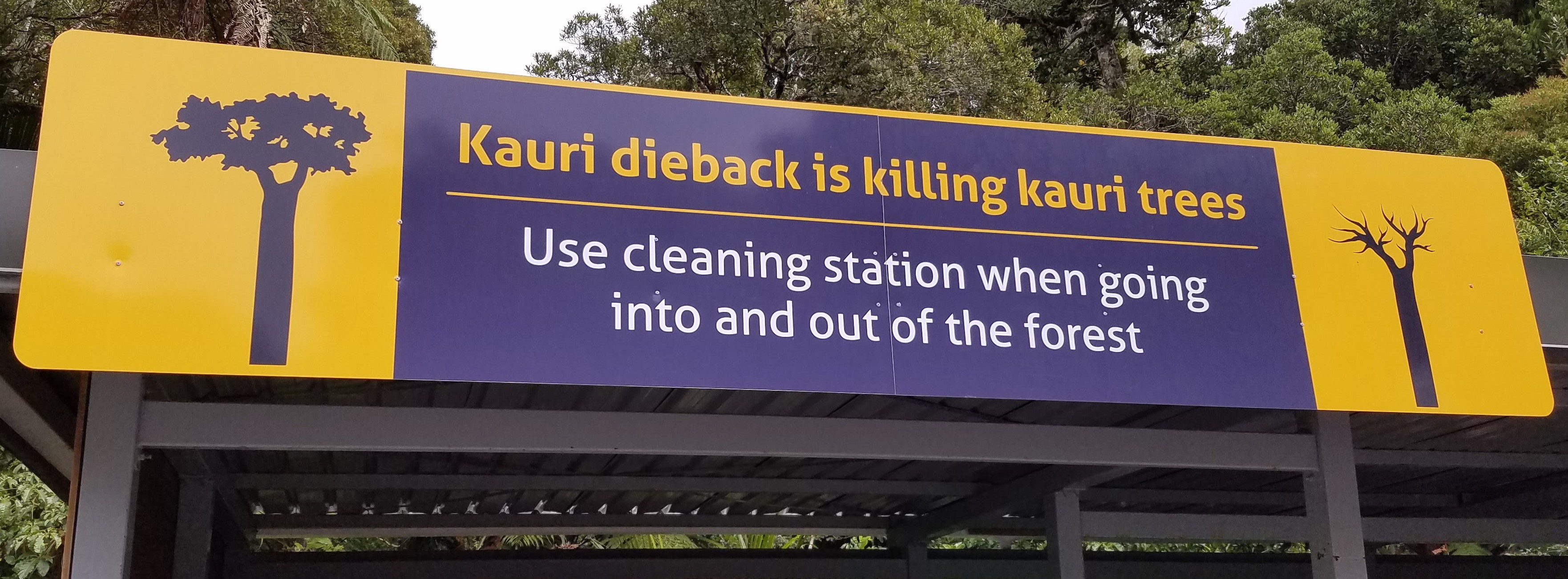

Cleaning stations provide disinfectant sprays to help protect the kauri forest

About half an hour southeast of Opononi on Route 12, the Twin Coast Discovery Highway, we pulled off the road in the midst of the Waipoua Forest so we could see Tāne Mahuta, New Zealand’s largest living kauri tree. Having begun to grow about the same time Jesus walked the earth, Tāne, named for the god of the forest, is also one of the oldest kauri. Kauri were once abundant in Northland, but loggers felled most of them during the nineteenth and twentieth centuries because the wood is so useful.

A conservation “ambassador” for the kauri trees

Gateway to Tāne Mahuta

We had the good fortune to arrive for our visit at the same time as a woman who introduced herself as an “ambassador” of the conservation group that cares for the kauri forest. She was able to tell us more about the trees, explaining that kauri are very good at healing themselves because they produce gum to seal wounds and prevent infection. However, gum cannot protect a tree from “dieback,” a fungal disease that infiltrates the root system and causes the tree to slowly starve to death. Conservationists encourage forest visitors to clean their shoes before and after entering kauri preserves (spray disinfectant is often provided) and to tread lightly around the trees—or better yet, stick to defined walkways—to prevent spreading the fungus and avoid putting undue stress on the trees’ root systems.

Tāne Mahuta is thought to be about 2000 years old

Because Tāne Mahuta is surrounded by other trees, and because it’s so large, it’s impossible to get an unobstructed view of the whole tree. From the observation area on the ground, we could assess its massive girth (nearly 14 metres), but we couldn’t see the top (over 50 metres from the ground) until we went back to the carpark and crossed the road to the picnic area.

Lunch al fresco in the Waipoua Forest

The weather was pleasant and the food in Jo-Ena’s chilly bins still had not been exhausted, so we enjoyed lunch al fresco at a table where we could take in the sights, sounds, and smells of the Waipoua Forest.

As we continued southeast on Route 12, the forest preserve gave way to land that had been cleared years ago for farms and pastures. We crossed the Wairoa River at Dargaville and then followed the river fairly closely for a while, passing an unusually pointy hill that we later identified as Tokatoka Peak. It’s not very tall—only 180 metres—but it’s striking because the land around it is mostly flat, so it seems to come out of nowhere. We learned that the peak is the hardened-lava core of an ancient volcano that eroded away (a geological rarity), and that in the past it was used as a lookout by a river pilot checking for ships sailing into nearby Kaipara Harbour.

Tokatoka Peak

Our last tourist attraction for the day was in Matakohe, half an hour beyond Tokatoka Peak. We’d heard that the Kauri Museum was worth a visit but we didn’t expect much, figuring that it would comprise a few rooms of local curiosities like the other small-town museums we’d visited. Boy, were we surprised! The place was huge (at 4500 square metres, it’s more than ten times the size of the museum at the Pacific Church History Centre) and seemed intent on describing every possible detail of the kauri tree’s growth, history, and uses.

A sculpture of a moa (an extinct flightless bird that was once common in New Zealand) in front of the Kauri Museum

Gum diggers

Chunks of fossilized kauri gum

The first few rooms were devoted to examples of kauri furniture and marquetry, others to jewelry and other ornaments made from fossilized kauri gum (a substance similar to amber), and another featuring chunks of raw kauri gum and a diorama of gum-diggers at work. We learned that for decades, digging kauri gum was as important to the local economy as logging. The gum was in demand around the world as a vital component of varnish until synthetic alternatives were developed in the 1930s, and it’s still used today in the varnish applied to fine string instruments.

Examples of kauri furniture

Next we went through a long corridor lined with rooms representing those of a typical “gracious” New Zealand home of the Victorian era. Each room was decorated with kauri paneling, woodwork, and furnishings; sumptuous fabrics; antique china and glassware; and a lot of bric-a-brac. The rooms also included life-size mannequins in period dress, whose features were based on real people who once volunteered at or contributed to the museum.

Reconstructed kauri sawmill

This marquetry triptych depicts the region north of Kaipara Harbour. (Notice Tokatoka Peak at the top right)

All those displays constituted only the first section of the Kauri Museum, an assemblage of interconnected buildings that reminded Nancy of the never-ending Winchester House in San Jose, California. The Kauri Museum’s Victorian-home corridor led to an exhibition hall about the size of a double gymnasium, where displays showed how giant kauri trees were logged and sawn into lumber—among other things. There was a collection of various types of saws and other woodworking tools. There was a section about the sawing and woodchopping competitions that are still going on among loggers and extreme sports enthusiasts in New Zealand today. There was an extensive display of vintage photographs of kauri lumbering operations. There was a re-created pioneer-era boarding house with life-size mannequins representing the millworkers who had lived in it. An upper level displayed a collection of guns and a series of model ships. There was even a commercial butter churn made of kauri wood, big enough to hold 200 pounds of butter. And on and on and on.

As visitors, we were overwhelmed by the sheer volume of things to see—way too much for the average tourist to take in, even if they were to visit every day for a week. As museum workers, we were appalled by the lack of protective measures for valuable historical artifacts; many fragile items were left exposed to light, dust, moisture, temperature fluctuation, and insects, and there seemed to be no security cameras or other anti-theft devices anywhere in the complex. After about an hour, Nancy decided she couldn’t handle the information overload any longer and had to escape to the gift shop until the rest of the group was ready to leave. She also spent several minutes filling out a visitor survey, on which she suggested that curators put 80 percent of the collection into secure storage and display only 20 percent at a time so visitors would not feel so inundated.

Dinner at Nando’s

Nando’s “Espetada”

Traveling east from Matakohe on the Twin Coast Discovery Highway for another half hour brought us back to National Highway 1, which soon expanded into a six-lane motorway as we headed south and approached the Auckland suburbs. It was after dark when we stopped in Silverdale for dinner at Nando’s, part of an international chain based in South Africa that serves grilled chicken flavored with a hot pepper sauce called peri peri. (U.S. Nando’s locations include Washington, D.C., Maryland, Virginia, and Illinois.) Nando’s is an upscale fast-food establishment on the order of Panera or Café Río, and the food is pretty good. We recommend the “Espetada,” chunks of grilled chicken and vegetables served on a hanging skewer.

After dinner we said goodbye to Kara and Jeff, as their road home led to Takapuna (an Auckland suburb) and ours went on to Hamilton. It was nearly 9 p.m. when we got back to our flat, too late to do any laundry or grocery shopping for the week ahead. We went to bed as soon as we had unpacked, having set our alarm for 1:45 a.m. so we could get up in time to witness the wedding of Nancy’s niece via Zoom. We are so grateful that the global COVID pandemic has provoked everyone to the realization that it’s possible to bring people together virtually to share in such celebrations, no matter where in the world they may be. Emery and Marc’s wedding took place in a little town near Amsterdam; the bride’s parents watched from Provo, Utah, and New York City; siblings in San Francisco and Seattle participated; more friends and family tuned in from across the U.S. and Europe—and New Zealand, of course.

All the events of this busy Easter weekend have reminded us that despite distance, disease, and societal dysfunction, there is always much to be grateful for, and much to celebrate.

I really don’t need to go to NZ after reading your blogs and enjoying the photos; you are splendid tour guides and food reviewers! Thanks again for a wonderful vicarious trip!

Just loved seeing our country through your eyes. What a treat. So proud of our heritage. Appreciated your feedback shared with the “museum”.

This was well worth reading if for no other reason than the line “Instead, it was lunchtime.” That cracked me up!