Initially, the only Church History missionaries assigned to attend Hui Tau 2021 in Kaikohe were Elder and Sister T (Alan and Wendy). As acquisitions and oral history specialists, they are responsible for making video and audio recordings for the Church History Department archives, so it made sense for them to go and record some key portions of the conference. Rangi and Vic planned to go, not because they had a Church History assignment, but because they had been asked by the organizers to do a presentation at one of the Sunday sessions. We (Michael and Nancy) didn’t have an official assignment, but we decided to attend simply because we didn’t want to miss such a historic occasion. Then, about the beginning of March, Elder and Sister E, the directors of the Matthew Cowley Pacific Church History Centre, were informed that the Church History Department wanted the entire event recorded, a task that would require all hands on deck. Thus they made arrangements for all of us to go.

Working out specific assignments for the weekend was difficult, however, because our instructions kept changing. Our supervisors in the CHD (headquartered in Salt Lake City) initially told us that all Hui Tau sessions were to be recorded on video. Because we knew that at times there would be concurrent sessions in multiple venues, we began making arrangements to borrow more recording equipment and to figure out who would be available to set up and run the cameras in each location. The CHD also asked us to secure digital copies of any PowerPoint presentations prepared by the speakers, and to make sure that we obtained signed donation agreements from each presenter. Wendy and Alan reminded us that the memory cards in our equipment could hold only so much, so we would have to switch out the card in each unit every two or three hours, download the recorded material onto a laptop, and wipe the memory card so it would be ready to use for the next round of sessions. They and Michael had just choreographed a complicated dance to make sure each camera got the necessary service at the appropriate times when we were informed that the Pacific Area (ecclesiastical) authorities didn’t want us to make any recordings at all. (Wait. Whaaaat?)

It was several more days before Melanie, the CHD’s Pacific Area manager, clarified that the Area authorities did not want us to make recordings of any sessions held in the chapel. Next, we heard that we could make audio recordings in the chapel, but no video. Later, that instruction was superseded by another stating we should go ahead and video everything, including sessions held in the chapel, except the Sunday night devotional. Two days before the event, we got word that we didn’t need to record any events on Saturday because the video crew from Church Communications/Publishing Services Department was going to cover them—but they might need one of our cameras and someone to man it during the performance events so they could get footage from multiple angles. When would we find out whether the CC/PSD group needed our assistance on Saturday? No one could tell us. It was all very confusing.

Jo-Ena and Diane obtaining signed permission forms from participants

The issue of obtaining permission from each presenter to record their speeches or performances was a thorny one. Signed agreements might give us permission to record a presentation for archival purposes, but not necessarily the right to share the recording with anyone outside the CHD. The Church Communications/Publishing Services Department is all about sharing with the public, so their crew uses an entirely different type of release form. Would we need to get both from everyone who might appear in a video so the Church wouldn’t get sued if a 15-second clip recorded by the CHD got used in an online news report? Sister E and Sister E (whom hereafter will be referred to as Jo-Ena and Diane to avoid confusion) began preparing donation agreement forms for every presenter and performer whose name we knew, and formulated plans as best they could to get the forms filled out and signed before recording began. Meanwhile, Melanie obtained consent from Elder B, the Area Seventy who was to preside over the event, to record both of his presentations, but later another authority told her that talks by members of the Seventy should never be recorded, except by official Church videographers. Did we qualify as official? No one could tell us.

Our personal assignments were still up in the air as we left Hamilton for Hui Tau 2021 in Northland early on Friday 2 April. The Church Communications/Publishing Services Department camera crew assured us that they would take care of recording the pōwhiri (welcome ceremony) on Friday afternoon, but as we left our accommodations at the Bayswater Holiday Home in Paihia the next morning, we weren’t sure whether CC/PSD was expecting our help with additional cameras or not. When we arrived on the field at Northland College, we offered them our services but were told not to worry because they had everything under control. So we staked out a row of seats under the central marquee and became spectators for a while. Meanwhile, Jo-Ena and Diane set up a station backstage where they could corner participants before they went onstage and have them fill out and sign the donation agreements required by the CHD.

A well polished kōrero from a 15-year-old

Remember the whaikōrero, the welcome speeches given by a series of distinguished men on Friday afternoon? Well, on Saturday morning, several teens and young adults were given the opportunity to perform their own prepared kōrero (talks) in te reo Māori, using the same dramatic, declamatory style we had heard in the pōwhiri. Again, we were unable to understand exactly what they were saying, but we were told that the content varied: some kōrero were sermons centered around a gospel principle, some described significant personal experiences, and others were recitations of the speaker’s whakapapa (genealogy) back to the Māori explorers who were the first human inhabitants of Aotearoa/New Zealand. It was clear that the purpose of this adjudicated event was to encourage young Māori to learn to express themselves not only in the language of their ancestors but also in the traditional style of their culture. From what we could tell, they were doing a pretty good job of it.

Joined by her mates, a twenty-something finishes her kōrero with a group waiata (song)

Only a few hundred people had gathered to listen to the kōrero, and many of those were not paying close attention, preferring to wander around the grounds and check out the food and goods for sale in the vendors’ area. Our status as senior missionaries granted us access to the tent set up for kuia and kaumatua (female and male elders), where juice, hot chocolate, and a variety of baked goods were being served at no charge. Later, we could avail ourselves of the lunch Jo-Ena had packed into “chilly bins” for our group: chicken salad on croissants, raw veggies, and fruit. By lunchtime, the crowd had grown significantly. Every folding chair within the three marquees was now occupied, and at least a thousand people were seated on mats rolled out on the grass in front of the stage. Groups of people who had brought their own collapsible chairs were crammed into the spaces between the marquees, all eagerly awaiting the start of the kapa haka performances at 12:30.

The crowd enjoys the kapa haka performances

Coordinated movements accompany songs and chants in kapa haka

The literal translation of kapa haka is line or row dance, but to define this traditional Māori art form simply as the Kiwi version of the Macarena or the Electric Slide would be a grave injustice. Kapa haka involves the group performance of a set of songs, dances, and chants based on a central theme and following a prescribed program order. The program usually opens with a choral waiata tira (warm-up song) and whakaeke (welcome song). These are followed by a waiata-ā-ringa (action song), which is accompanied by symbolic gestures performed by the group in unison. When the women are not using their hands for any other action, they flutter them at their side throughout the entire performance. The constant movement might symbolize light shimmering on water, leaves fluttering in a breeze, the flicker of a fire, or even the stirring of the Holy Spirit.

Dramatic gestures are an important feature of kapa haka

A mother performs with her baby strapped in front

One of the most distinctive features of kapa haka is the performers’ dramatic facial expressions: pūkana (widened eyes), whētero (extended tongues), bared teeth, and jutting chins. Such gestures are employed by both men and women to convey passion as well as to demonstrate fierceness, especially during the haka (challenge) segment of the performance. This dance, accompanied by a chant, is performed by the men. Although it probably originated as a war dance, it doesn’t necessarily signify belligerence. Some of the haka we witnessed at hui tau told about the coming of Latter-day Saint missionaries to New Zealand, the restoration of the priesthood, and the vital responsibilities of fatherhood. A haka that we found particularly effective was one illustrating the dark, adversarial power that momentarily overcame Joseph Smith as he was trying to pray vocally for the first time.

The haka usually is followed by a mōteatea (chant) and perhaps another waiata, and then Nancy’s favorite part: the poi. Poi are soft fabric balls, a little larger than tennis balls, which are attached to the end of a cord. Each woman takes a pair of poi in each hand and rhythmically twirls them in time with the music. Poi were devised by Māori long ago as a means to help warriors develop strength and agility in their hands, wrists, and arms so they would be better prepared for combat; women used them, too, to increase fitness for their own tasks. Poi also were used by women on long waka (canoe) voyages because the sound of the balls striking their hands helped the men row in sync with each other. In time, the exercise evolved into a truly beautiful art form. The effect of watching a skillful kapa haka poi presentation is similar to that of watching a phalanx of baton twirlers, or a rhythmic gymnastics team performing with ribbons.

A young daughter joins her mother impromptu to prove she already knows the routine

Music for the whole kapa haka program is primarily vocal, with some guitar accompaniment. Percussive rhythm is provided by hand-clapping, body-slapping, and foot-stomping; occasionally, rākau (wooden staves) are used to strike the ground. Some programs include a tītī tōrea segment, in which pairs of smaller sticks are rhythmically manipulated to music. The program ends with a whakawātea (closing song) sung by the entire group, typically three or four dozen people.

The Labour Missionary kapa haka group has been performing since 1958. Several members of this group are over 80 years old

At Hui Tau 2021, twelve groups performed. Most participants were adults, with some teenagers and a few younger children participating. A group from Rotorua was composed entirely of teenagers, about half of them non-LDS. The bishop of a ward in the Rotorua area had decided to form a teen kapa haka group a couple of years ago to help the youth in his congregation learn to appreciate their Māori heritage, to unify them, and to build their faith. He encouraged the kids to invite their friends to join. When he learned that the Kaikohe and Whangarei Stakes were planning a hui tau and inviting kapa haka groups from other stakes to come and perform, he asked his group if they were willing to commit to more practices every week and to participate in fundraisers so they could go. Not only did everyone agree, but the prospect of such an exciting project attracted even more participants. As part of their training, the youth learned traditional crafting techniques so they could make their own props—poi and rākau—and costumes: pari (woven bodices) and piupiu (flax kilts) for the women, and tātua (woven waistbands) and maro (short kilts) for the men.

The costumes of the other kapa haka groups performing at Hui Tau 2021 spanned the spectrum from elaborately traditional to simple custom T-shirts with uniform skirts and pants. Many groups employed standard church music and traditional Māori songs to support their themes, which could be based on gospel principles, scripture stories, or historical subjects, but some of the presentations featured original words and music. Groups from as far away as Wellington participated. We had seen the Hamilton kapa haka group perform three or four times before, but never as well as they did this weekend. The group comprises members of three of the four Hamilton stakes (including a few from our own ward), plus a number of non-Latter-day Saints from the community. The Hamilton Temple View Stake has its own group, called Tuhikaramea, which was the original Māori name for the Temple View area. We thought their presentation about the gathering of Israel was the classiest of the afternoon. Here’s a sampling of their performance.

With twelve groups each performing for 15 to 20 minutes, it was a long afternoon–and a hot one. Northland had seen a lot of rain in the days leading up to hui tau, but all the prayers sent heavenward for fine weather must have persuaded the Lord to send the clouds elsewhere for Easter weekend. Michael missed a few of the kapa haka performances while he took Rangi over to the Kaikohe chapel to run through her presentation for Sunday—ostensibly, to ensure that the chapel’s projection equipment was compatible with her laptop, but also to help Rangi plan how to keep her presentation within the 50-minute time limit.

Nancy connected with Sister Eden K, the daughter of our bishop, who is serving a proselytizing mission in the Northland area

Rangi has been doing slide presentations on various aspects of New Zealand Church history for decades, but usually she’s the only one on the program and thus doesn’t have to worry about leaving time for someone else. And because she’s been doing these presentations for decades, she often reuses material from previous programs, and we’re never sure that the file she created for the latest iteration didn’t get corrupted when she tried to insert a video clip made back in 1994 with software that’s now obsolete. In his role as the tech support manager for the MCPCHC, Michael has spent a lot of time helping Rangi organize and update her digital files, and in the process also has tried to help Rangi organize her presentations—no easy task when you’re working with someone who is accustomed to presenting “as the spirit moves.”

Booths outside the performance area offered food and general merchandise for purchase

Near the end of the kapa haka event, Michael returned to his seat under the marquee. When Nancy asked if everything had gone OK with Rangi’s dry run at the chapel, he rolled his eyes and said, “It was a disaster”—not due to technical difficulties, but because Rangi had waaaay too much material she was planning to share. So as soon as the last kapa haka group was finished, we did our best to quickly gather our cohort so we could reload the vans and get back to Paihia, where Michael and Rangi would have some serious work to do.

Michael and Rangi were not the only ones who had some serious work to do when we finally pulled into the carpark at the Bayswater Holiday Home, because the simple dinner menu Jo-Ena had planned—two types of burgers—turned out to be not as simple as it sounded. Ground beef needed to to seasoned and formed into patties; chicken fillets needed to be pounded and sautéed; cheese needed to be grated; tomatoes sliced, lettuce washed; buns split and spread with garlic butter; meat cooked, and finally everything had to be assembled and put under the broiler to melt the cheese and perfectly crisp the edges of the buns. Complicating this process was that we could not really get started until our head chef arrived to give us instructions, but Jo-Ena was driving the van that had to make a 40-minute detour to return a tablet to Melanie. Meal preparations didn’t get fully underway until about 8:00 p.m. and it was 9:00 before the burgers were ready to serve. But we have to admit, they were worth waiting for.

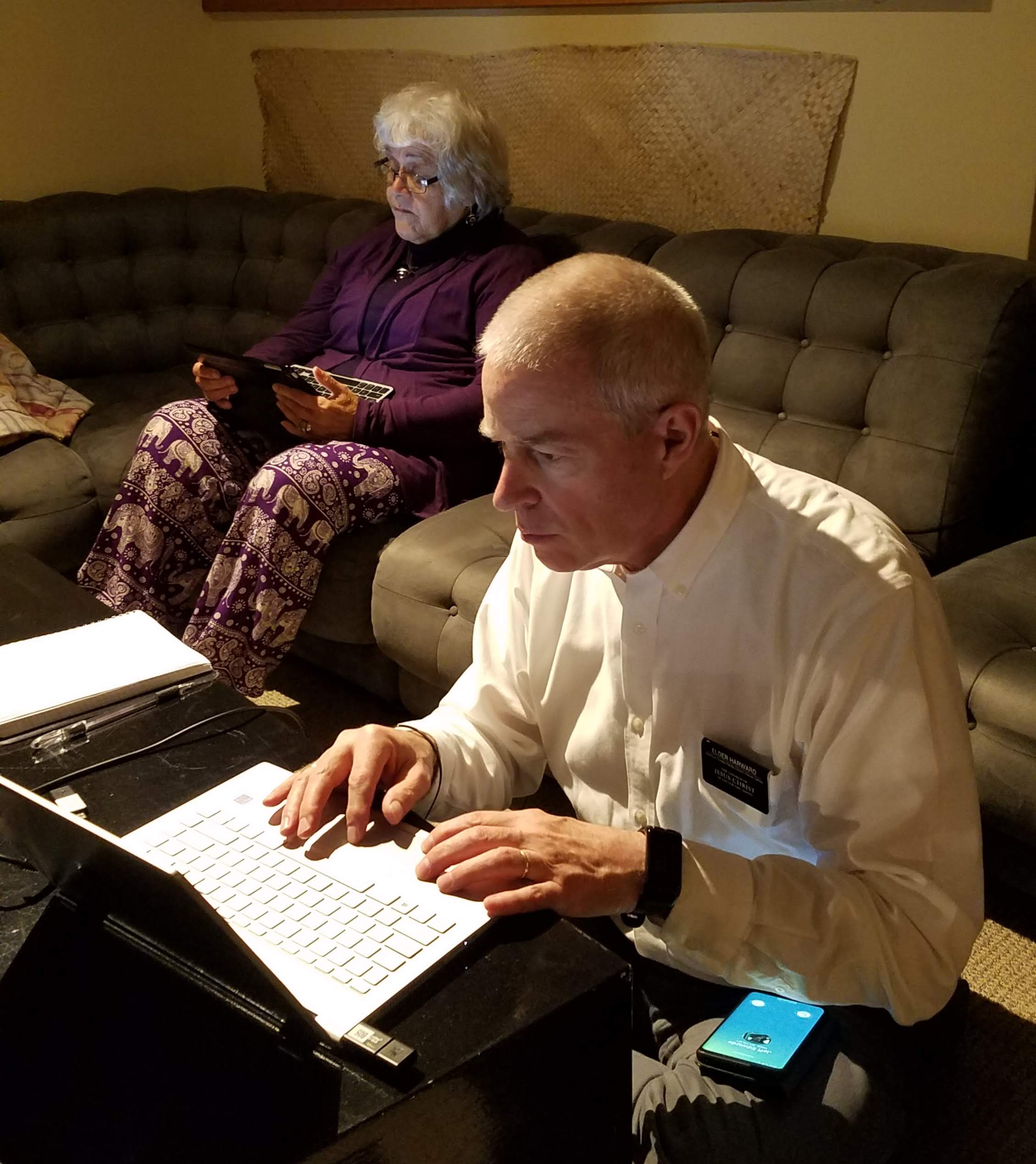

Michael sequesters Rangi to edit and finalize her presentation

Meanwhile, Michael sequestered Rangi in front of a couple of laptops in a far corner of the lounge. Gently and patiently, he persuaded her to identify the key points she wanted to make in her presentation, and then helped her eliminate extraneous material so that she could stay within the time constraints. Once Rangi had chosen the half-dozen videos she really wanted to include, Michael edited the clips and inserted them into a single PowerPoint presentation so she wouldn’t have to switch from file to file during the presentation. That done, they took a short break for dinner, and then Michael coached Rangi through a couple of rehearsals until it was time for her to retire. She went to bed happy—and ready.

Cheap ice cream in Paihia

After we said goodnight to Rangi, several of us walked up Marsden Road to get some ice cream. Our intended destination was Mövenpick, a Swiss chain that we knew was good but expensive. However, when we noticed that Cellini’s Ice Cream across the street was selling cones for about 40 percent less than Mövenpick, we decided to give Cellini’s a try. Their product was not as good as Mövenpick’s, but satisfactory for the price. Nancy ordered watermelon-mint sorbet, but couldn’t really taste the watermelon until later, when she burped!

Paihia wharf at night

Had we stayed in Kaikohe for the evening instead of returning to Paihia, we could have attended the Hui Tau 2021 Ball and danced the night away. Had the ball been held in the gym at the Kaikohe meetinghouse as originally scheduled we probably would have gone, but when we heard that the venue had been changed to the athletic field at Northland College to accommodate more people, we decided to skip it because the idea of trying to dance on stubbly grass wasn’t very appealing. So instead, we walked along Marsden Road, eating ice cream and admiring the lights of waterfront restaurants shimmering on the Bay of Islands.

Wow! On many levels.

Dear Michael and Nancy,

What an amazing adventure you are having. You document it well. It’s wonderful that the Maori traditions are being preserved. It was fun to see both of you pictured. I’m at my son David’s home in Sammamish WA, a suburb of Seattle, where I am planing to move to a nearby retirement community. I’ll return to Chicago soon to get ready to make the move the end of October. Hope to see you sometime. Love, Charlotte

We’ll plan to visit you in Sammamish sometime in 2022. Our youngest daughter and her family live in the Seattle area, so we are more likely to travel there at this point than to Chicago. May the Lord smooth your path as you make this big transition to a new home!

What a treat the video is! I love the variety of styles you shared and found them all less scary than the ones we see performed at All Blacks rugby matches! And, of course, now I want a burger on a garlic butter bun – thanks Michael!