Delivered by Nancy Harward in a sacrament meeting of the Montgomery Ward, Cincinnati Ohio East Stake, Sunday 12 December 2021

The Gift Room at the Pacific Church History Museum

The Matthew Cowley Pacific Church History Centre in Hamilton, New Zealand, where Michael and I have just spent two years as full-time Church History specialist missionaries, includes a fairly large museum devoted to the history of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints in the South Pacific. The first room one enters when visiting the museum is called the Gift Room because it includes a display of items given to Church leaders and missionaries by people from the Pacific as expressions of gratitude for the gift of the gospel of Jesus Christ.

Missionaries who served among the Māori of New Zealand during the nineteenth and twentieth centuries often returned to their homes in America with precious taonga (treasures) bestowed on them by grateful Māori converts.

Elder John William Platt served in New Zealand from 1886 to 1889. Missionary work among the Māori was flourishing at that time, but mission president William Paxman was concerned that many of the natives the missionaries were trying to teach could not speak English, and many more were illiterate. Elder Platt, who was from southern Utah, had just completed training at Brigham Young Academy to become a schoolteacher when he received his mission call, so President Paxman gave him a special assignment to teach Māori—both children and adults—to speak English and to read and write. Platt served in that assignment for two and a half years, and then served for another six months as a proselytizing missionary.

Elder Platt’s whalebone kotiate

While in New Zealand, Platt developed a close friendship with the rangatira (chief) of one of the Māori tribes he worked among. In 1888, this chief presented Elder Platt with a kotiate, a short hand club carved from whalebone. It looks something like a violin, but its purpose is very different; a kotiate is a weapon of war, used to kill and maim. This kotiate’s worn edges suggest that it had seen years of use. I like to think that the Māori rangatira who gave his kotiate to Elder Platt wanted his missionary friend to know that, like the Anti-Nephi-Lehies in the Book of Mormon, he had renounced war because he had been converted to the gospel of peace.

The kitchen towel from Judy

Elder Harward and I could start our own little museum with the gifts we were given by New Zealanders who were grateful for our service in their country as missionaries. Here’s one of the precious taonga we received: a kitchen towel. “A kitchen towel?” you might ask. “What is so precious about a kitchen towel?” Well, let me tell you. This one came along with a card explaining why our friend Judy wanted us to have it. “Have you ever stopped to think about what a towel can be used for?” she asked.

Think, for example, about the towel used by a busy parent to keep their home clean, or to gently dry the tears of an injured child. Think about the towel used by a laborer to wipe the sweat from their face and the grime from their hands at the end of a long day. Consider the way a doctor or nurse might use a towel to clean and bind a wound. And think about how a boxer’s manager might “throw in the towel” to spare the fighter from further injury, or how a rescuer might wrap a towel around someone just saved from drowning. In each of these instances, a simple towel represents a vital act of service.

Now remember that while Jesus was eating with his disciples for the last time before his crucifixion, “he arose from dinner and set aside his outer clothing and took a towel and tied it around himself. Then he poured water in a basin and began to wash and dry the feet of the disciples with the towel tied around him” (John 13:4-5, translation by Thomas Wayment). With this washing ordinance, the Savior transformed an ordinary towel into the symbol of an extraordinary act of loving service.

Judy, the museum guide who gave us this towel, had a neurological disability that made it difficult for her to tolerate being in a large group, yet she came to our farewell party because she loved us and wanted to say goodbye. This little gift will always remind us of Judy’s devotion to the Lord and her faithful service as a volunteer at the Pacific Church History Museum.

Some gifts are not as tangible as a towel or a whalebone club. Many gifts are spiritual, given by God for the benefit of his children.

A missionary named John Austin Abbott, who served in New Zealand from 1898 to 1901, witnessed the manifestation of a spiritual gift given to a woman by a loving Heavenly Father. In his autobiography, he wrote:

One day, I was called to go down the river [from Papawai] several miles to a Maori settlement to hold funeral services for a Maori baby. The family were members of our Church. A number of neighbors and friends had gathered at the home where the services were held. As I was alone there, the singing, the praying and preaching all fell to my lot. A white lady who lived near-by came into the services. As I spoke in the Maori tongue, I noticed the white lady crying. After the service, she came up to me and said she wanted to make my acquaintance. She said she had lost a baby about three weeks before, and that her Presbyterian minister had said it had gone to hell and would be consigned to everlasting flames because they had neglected to have it baptized. She said she could not believe that God would be so unjust as to send a little innocent baby to hell, but said she knew something had happened. “I do not know one word of Maori and yet I understood every word you spoke. And I’ve learned from your sermon that little children are saved through the atoning blood of Christ, and that they are pure and innocent and need no baptism.” She said, “Oh, is it true that my baby is saved? How is it that I could understand you when I didn’t know one word of Maori?” I told the lady it was true her baby was saved in the atoning blood of Christ and that the God of Heaven had made it known to her by the interpretation of tongues which is a gift of the Holy Ghost, that her prayers had been answered. She wept for joy and I wept with her. To know that the Lord had given her the interpretation of my sermon, was a great source of joy to me. She asked to walk to the cemetery and talk with me. After returning, she asked me to visit her home and talk to her husband. I made a number of calls at their home and soon, they with their eight children, came into the Church (John Austin Abbott, John Austin Abbott: An Autobiography 12 Aug 1871 – 8 Mar 1954. Ed. Mary Lou [Abbott] Shaw, Fair Oaks, California, 1992, pp. 30-31).

Records of inspiring experiences such as this one from Elder Abbott’s autobiography are among the most valuable gifts in the collections of the Pacific Church History Centre. I am so grateful for the people who wrote about their experiences, and for those who preserved these precious records and then donated them to the Church History Department so they could be shared more widely. One of the greatest gifts I received as a Church History missionary was the opportunity to spend time reading stories recorded by faithful Saints who testified of God’s love and the blessings that come to those who trust in him.

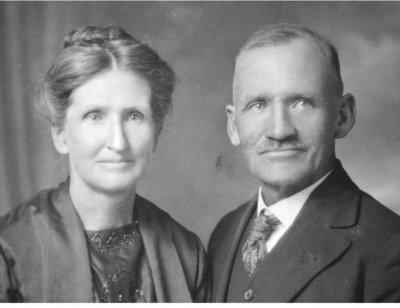

Ida and Oliver Dunford

Let me share an excerpt from the journal of another American missionary who served in New Zealand in the 1890s. Oliver Cowdery Dunford and his new wife, Ida Ann Osmond Dunford, were assigned to work among the Māori in the Hawkes Bay area. Ida taught school and was often left to serve alone while her husband and other elders traveled around the district, preaching, regulating the affairs of the Church, and giving priesthood blessings. On this particular occasion, however, it was Oliver who was left alone while traveling. One Friday evening in 1890 he wrote about having arrived at a village just as the sun was setting, cold, wet, and sick after having to ford a river on horseback. “[I] found none of the cheering scenes of Home to invite my spirits to cheer up,” he said. “A kind old gentleman took my horse and cared for him, while I went into an old rush hut and lay on a mat by a smouldering fire (that was an aggravation) to nurse my head and my weary spirits.” Although the villagers were kind, bringing him food and a pillow and trying to make him as comfortable as possible, Elder Dunford did not get any better. Moreover, “the weather was very stormy,” he said, and the little hut where he lay “was situated on a hill at the foot of which the troubled ocean tossed and heaved about wildly. I could see and and feel that little building twisting and bending before the wind and some times I felt as though it would tumble into those ferocious waves.”

By the next evening, Elder Dunford was desperate for relief. “Feeling very sick,” he said, “I anointed myself with consecrated oil, then prayed to God to restore me to health, and in the name of Jesus Christ & by the power and authority of his priesthood, I rebuked the sickness that was praying upon my system. I then retired and slept most sweetly.” The next day he reported: “I awoke about sun up, feeling free from everything that was unpleasant. How, I did feel to thank God for answering my prayers and restoring me to health” (Oliver Cowdery Dunford, Missionary Journals, vol. 1, pp. 52-53).

May I suggest that if you are stumped as to what to give someone you love for Christmas, one of the best gifts you could possibly give to a family member or friend is a written account of a meaningful experience you have had. No doubt Skyler Carter, the great-great-grandaughter of Oliver and Ida Dunford and a member of Montgomery Ward, would attest that one of the best gifts you can leave your posterity is a written journal or life history that includes your testimony of Jesus Christ—or perhaps your struggle to develop and maintain that testimony. These are priceless gifts that will keep on giving for generations.

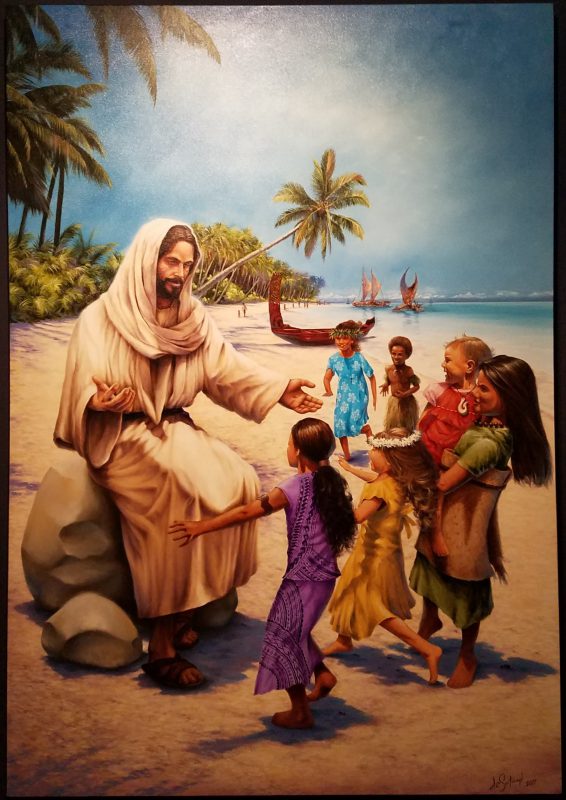

“Christ in the Pacific” by Dave Sotogi

Returning to the Gift Room at the Pacific Church History Museum: On the wall opposite the display of artifacts representing the museum’s gift collection is a large painting. It depicts Jesus Christ, sitting among palm trees on the shore of a Pacific island. He is surrounded by a group of excited children, each dressed in the traditional costume of a different South Pacific culture. In the background are several types of canoes, each representing the traditional watercraft of various island cultures. More people are getting off those boats, coming to meet Jesus. Often, when I would take people through the museum, I would stop in front of that painting and ask them what they saw in it, what it meant to them. I will never forget the response I got from a Samoan woman whom I was training as a volunteer museum guide. With tears welling up in her eyes, she said, “I see my own people. The Savior came to my people. The Savior loves my people.”

That painting of the Savior is in the Gift Room at the Pacific Church History Museum to remind visitors that “God so loved the world that he gave his only begotten Son” (Joh 3:16), and that he remembers “all the nations of the earth,” including “those who are upon the isles of the sea” (2 Nephi 29:7). It’s there to remind visitors that “Jesus Christ, the Redeemer, the light and life of the world, gave his own life, that as many as would believe might become the sons [and daughters] of God” (Doctrine & Covenants 34:1-3)

During this Christmas season, I would exhort you, as did Moroni in the last chapter of the Book of Mormon, “that ye remember that every good gift cometh of Christ” (Moroni 10:17-18) May we always choose good gifts to exchange with each other at Christmastime, and may we always be grateful for the gifts of life and love bestowed so generously on us by our Heavenly Father and our Savior Jesus Christ.

Thanks for sharing all the testimonies and examples of the faithful Saints!

Nancy it was so wonderful seeing you and Michael Sunday. I enjoyed your talks and am so glad to hear the experiences your shared. It’s so true that all gifts are from our Heavenly Father and Savior, and so nice to be reminded of it every once in a while. Life is the most precious gift and I’m so grateful every day for it. I thought about the towel after your talk and the wonderful purpose of its use. The gift room i would love to hear the stories of them you have given me the gift of friendship and I’m eternally grateful. Thank you.

Thank you so much for sharing this. I wish such paintings were hung all around the world in our churches so that we can be reminded that the Lord loves ALL His children and all visitors and members can see themselves in the art in our chapels.