With another summer Sunday afternoon stretching before us after church, we decided to drive to Kawhia (pronounced KAH-fee-ah), about 80 kilometres southwest of Hamilton. The village is located on the southernmost of the Waikato Region’s three major inlets on the Tasman Sea. Freshwater enters Kawhia Harbour by means of the Oparau River, which begins in streams trickling down the slopes of Mount Pirongia.

With another summer Sunday afternoon stretching before us after church, we decided to drive to Kawhia (pronounced KAH-fee-ah), about 80 kilometres southwest of Hamilton. The village is located on the southernmost of the Waikato Region’s three major inlets on the Tasman Sea. Freshwater enters Kawhia Harbour by means of the Oparau River, which begins in streams trickling down the slopes of Mount Pirongia.

The winding road to Kawhia

We drove through foothills in the Pirongia National Forest to reach our destination, traversing roads so twisting and narrow that few cars venture along them, let alone any tourist buses.

So why make the tortuous journey? We wanted to go because we had read that Kawhia is historically significant, the final resting place of the waka Tainui, one of the seven voyaging canoes that brought the ancestors of the Maori to this land in the 1300s.

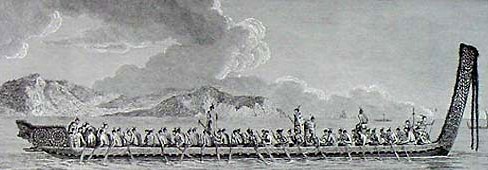

Depiction of the Tainui

The Tainui is said to have first landed on the Bay of Plenty, but continued on up the east coast of the North Island to Waitemata on what is now Auckland’s Pacific harbor. Hoturoa, captain of the Tainui, never seemed satisfied with any place he landed along the east coast, so he and his crew portaged the waka about two hundred meters from Waitemata to Manukau, now Auckland’s Tasman Sea harbor, so they could explore the shores along that side of the island. From Manukau, Hoturoa sailed up and down the west coast, finally returning to the wide inlet at the mouth of the Oparau River where he moored his ship for the last time.

Fodor’s New Zealand described some of this history and mentioned that there was a small museum in Kawhia, worth a trip “off the beaten path.” Cool, we thought. Let’s go see the 700-year-old waka. But finding the Tainui was not as straightforward as we expected.

Kawhia Harbour as seen in the distance from a viewing point on the road through the Pirongia Forest Reserve

Hoturoa’s choice of Kawhia Harbour is puzzling, because although it looks to untrained eyes like a perfect place for a ship to shelter in a storm, it’s not. Prevailing winds and ocean currents actually exacerbate storm surges within the harbor, and when the tide goes out, it really goes out, so it’s not suitable for ships with a deep draft. Nevertheless, Hoturoa decided to establish a settlement there and built a whare wananga (sacred house of learning) on a hill overlooking the shore, calling it Te Ahurei (The One and Only). The fortified village of Motungaio that grew up around Te Ahurei became one of the most powerful pa on New Zealand’s west coast during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. When Europeans discovered the area in the early nineteenth century, they established a trading post and did good business in timber, wheat, and flax until the Waikato Wars of the 1860s disrupted commerce. Trade eventually resumed, peaking during the first part of the 1900s, but as commercial shipping vessels got bigger, the limitations of Kawhia Harbour brought an end to its career as a thriving port.

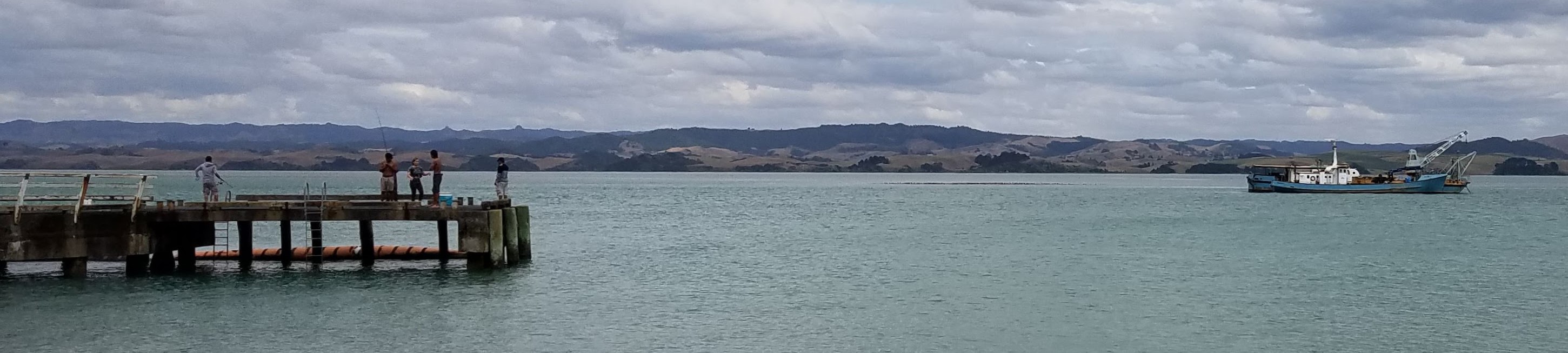

Kawhia Harbour from the shore

Kawhia has not done much to position itself as a tourist attraction to offset the commercial decline of the last century. What one sees along the wharf in Kawhia today seems to be what one would have seen in the 1940s, only more run-down: half a dozen small fishing boats, a general store, a church, a few cafes, a hotel, a picnic ground, a public toilet, and the Kawhia Regional Museum and Gallery. The latter is housed in the hundred-year-old former town hall, and contains the type of curiosities and musty memorabilia one would expect from a small-town museum.

Collection of toki (stone adzes) and other woodworking tools from the Classic Maori period (18th century)

Facsimile of a 140-million-year-old giant (1.5 meters high) ammonite fossil found by roadworkers on the highway outside Kawhia in 1977. The original is in the national Museum of New Zealand in Wellington

Bones from a moa, a giant ostrich-like bird that lived only in New Zealand. It became extinct about 1500 BCE

The 40-pound “Kawhia Snapper,” caught in local waters in 1941

Collection of vintage firefighters’ equipment

Telephone switchboard from the early 20th century

Butter churn used in a commercial dairy in the early 20th century

Boatbuilder’s boring device, used to drill holes in the keel for propeller and rudder shafts

Michael learns about whaleboat racing. Although Kawhia was never a major whaling station, since 1910 the town has sponsored an annual whaleboat regatta; every New Year’s Day, teams from other coastal towns compete in 11-meter, five-oared whaleboats that have been specially designed for racing, like this antique one

Collection of traditional woven handbags

On the day we visited, the gallery portion of the museum displayed the art and handiwork of several local artists.

Tekoteko (carved human figure) by Massey Ormsby. Titled Te Hiahia (The Desire), it represents the desire of King Tawhiao to end the Waikato Wars. He ordered his warriors to lay down their weapons, hoping that their offer of peace would be balanced by an offer of justice from the British

Another figure by Massey Ormsby, representing Kuwatawata, the gatekeeper at the juncture between the human world and the spirit world

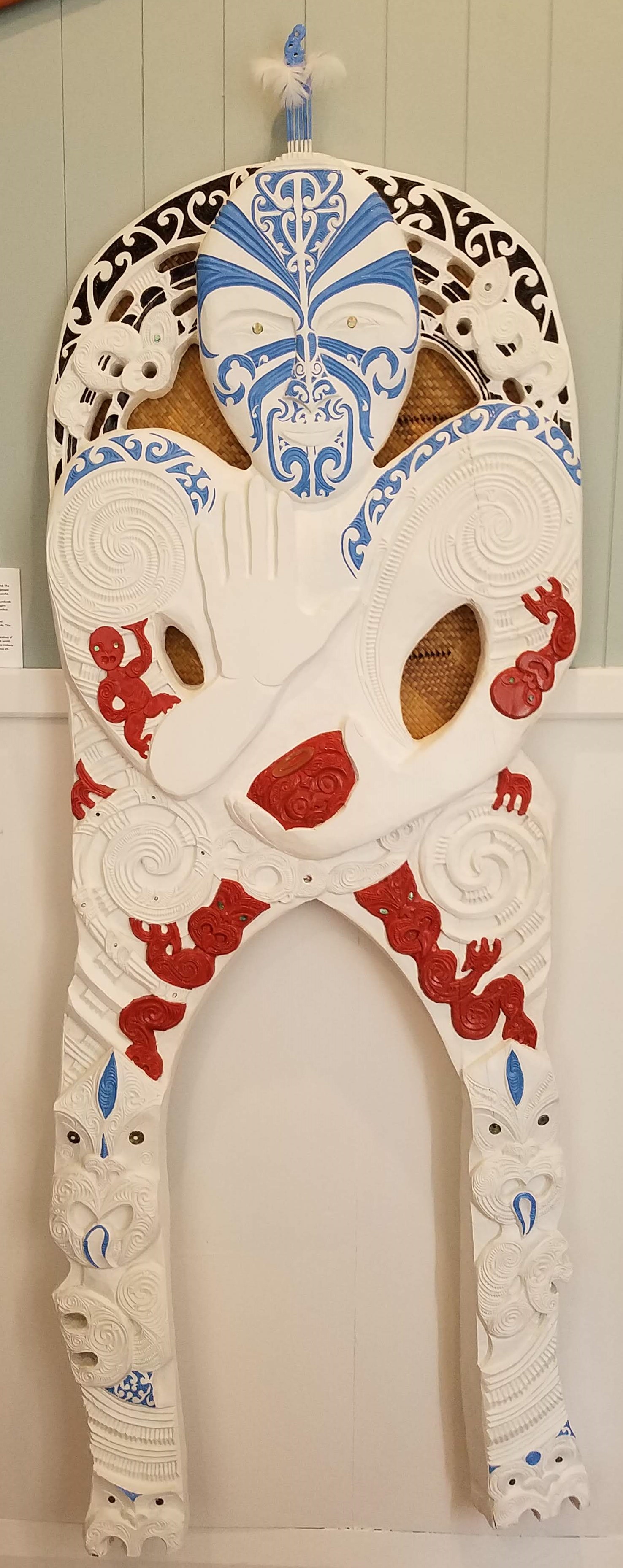

The Carved Custodian of Conceptual Knowledge

A large contemporary yet traditional sculpture by master carver Te Kuiti Stewart stands on the waterfront outside the museum. It is called “The Carved Custodian of Conceptual Knowledge,” and is “created from the form of an ancient wind instrument that calls and sings to the world,” the artist explained. “Winds of yesterday are songs of today, songs of today become winds of tomorrow.”

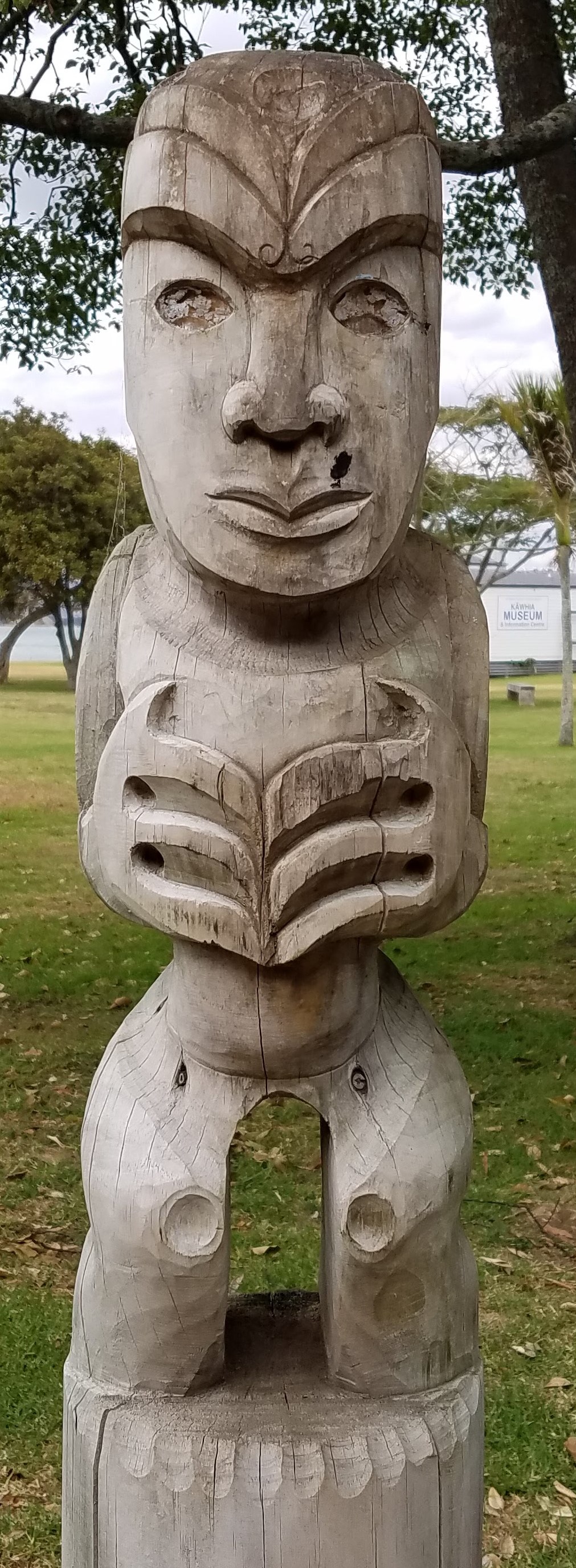

Tekoteko at the Omimiti Reserve

The central feature of Kawhia’s waterfront is a small wharf, where a few fishing boats motored in and out during the afternoon. Had we been so inclined, we could have hired one of them to take us out on a fishing expedition. Or, we could have hiked four kilometres out to Te Puia on the ocean side of the harbor, where natural hot springs bubble up through the black sand at low tide, much to the delight of people who think slathering themselves with hot black mud is either beautifying or therapeutic. A few local families were content to sit on the tiny beach just outside the museum, taking advantage of the warm day, which so far had been rainless despite a lot of brooding clouds.

Even tekoteko cannot protect picnickers from encroaching seagulls

Another family was picnicking in the Omimiti Reserve, a park next to the museum that bears the original name for this area on Kawhia Harbour.

During the town’s heyday as a commercial port, what is now the Omimiti Reserve was known as “The Strand,” the site of shipping company offices, a newspaper printer, and a boarding house. Today the reserve is open green space surrounded by Maori tekoteko (carved human figures) representing guardian ancestors. Tekoteko are traditionally used to mark and protect homes and marae (community gathering areas).

After leaving the museum, we spent another half hour or so walking around town, but we never found the remains of the Tainui, the historic waka that had drawn us to visit Kawhia in the first place. So what happened to it?

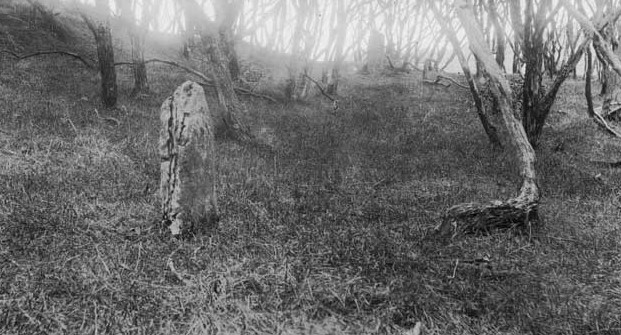

An old photo of the final resting place of the Tainui. The stone markers indicate the location of its prow and stern

Hoturoa, captain of the fabled canoe, ceased exploring when he landed in Kawhia Harbour because Rakataura, the tohunga (holy man) who traveled with him, recognized this as the landing place he had seen in vision before they left Hawaiiki. Thus Hoturoa’s men dragged the Tainui up the hill to Te Ahurei, the sacred house of learning, and buried it in the marae outside.

Tangi-te-korowhiti, the pohutukawa tree on Kawhia Harbour where, according to tradition, the Tainui was moored for the last time. Regarded as hapu (sacred) by the Maori, the ancient tree was heavily damaged by fire in 2005, but survived

Fodor’s New Zealand had failed both to mention that the ship had been buried and to point us toward its grave at the Maketu Marae, located on the other side of the harbor from the town of Kawhia. That was just as well, because as yet we don’t know anyone who might invite us onto the marae. Maybe someday we’ll be able to go back and pay our respects to one of the ships that started it all.

I really liked your post. It was informative and respectful, with wonderful photos. My descendants the Salmon Family arrived at Kawhia from Scotland in the 1860’s embracing the Maori culture and traditions. There was my Great, Great Grandfather and three of his sons becoming very immersed in the future of integration , education, and development.