Saint Petersburg’s importance as Russia’s commercial link with northern Europe became evident to us this morning as the Star Breeze made its way on and on and on through the port, passing all manner of container ships, barges, tugboats, cranes, loading docks, warehouses, and piles of scrap metal, toward the pier on the Neva River where the cruise ships dock—right in the heart of the city. The ship didn’t stop moving until we were ready to go upstairs for breakfast, where we could begin to enjoy the same grand views of the city along the Neva that Russian emperors had enjoyed since the eighteenth century.

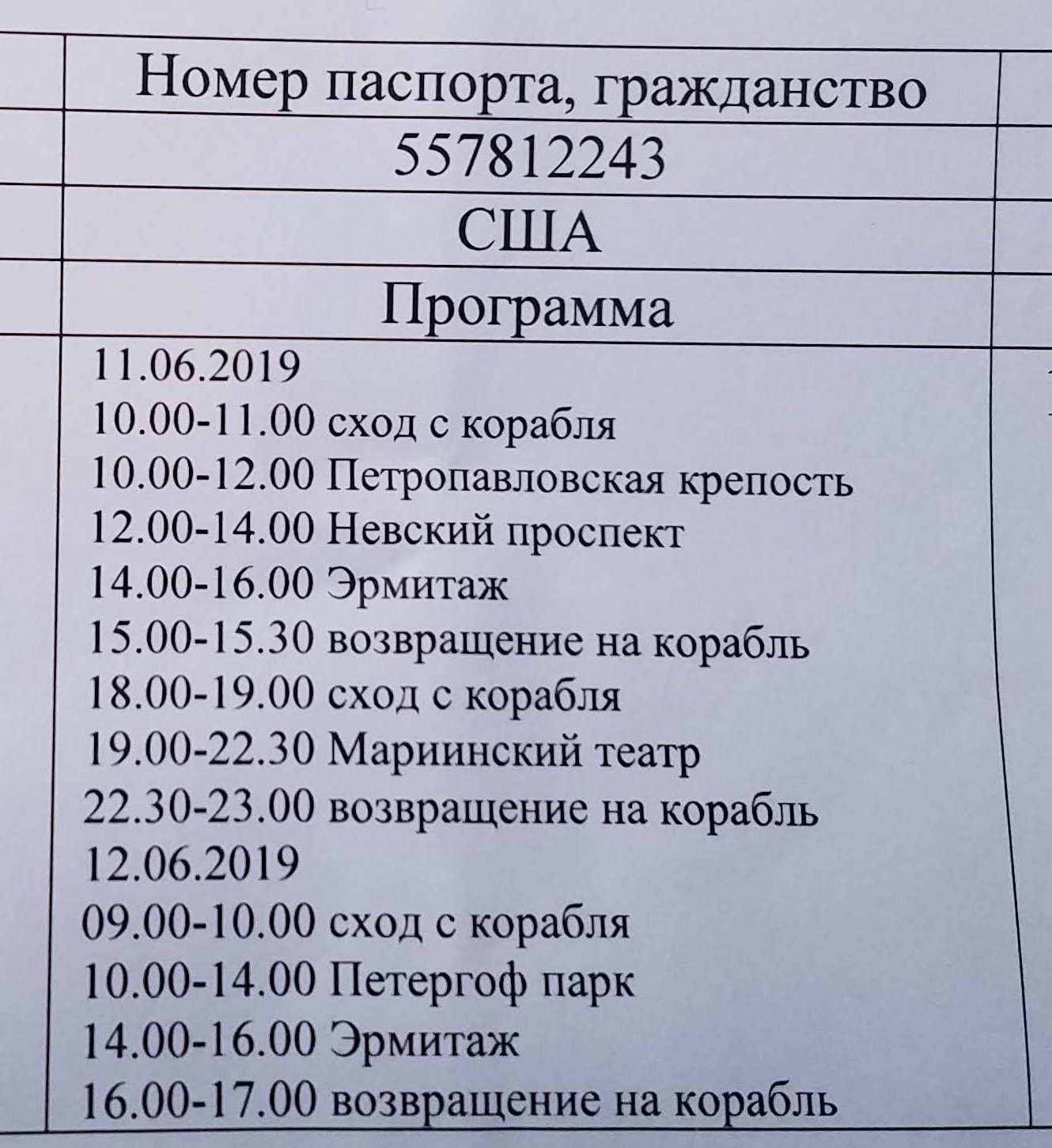

Each of us was given a copy of the day’s itinerary, but we didn’t find it very helpful

Once Michael had finished his French toast and Nancy her spinach and ricotta crèpes, we grabbed our passports, backpacks, and lunch (sandwiches and fruit gleaned from the breakfast buffet), and headed off the ship. We had been warned that Russian customs control could be gruelling, but even though the unsmiling officers examined both our documents and our faces carefully, it wasn’t nearly as bad as we had anticipated. Soon we were in the hands of Marina, the guide who would keep close watch over us during our tour of the city.

Saint Petersburg may bear the name of the humble fisherman Jesus chose as his first apostle, but the city’s real patron is another Peter: the enlightened “Great” czar who brought Russia out of its medieval past and transformed it into one of the world’s most powerful, influential nations. (By the way, czar is the Russian form of Caesar; Russian rulers began taking this title in the fourteenth century, but it was Peter who really insisted on making his status equal with that of the Holy Roman Emperor.)

Peter had become czar at age ten but had to share power with his mother and a sickly half-brother until both of them died. While he waited for his chance to assume full power, he studied languages, practiced military manoeuvers with toy soldiers, and learned to both build and sail ships. When the half-brother died in 1696, Peter was 24 years old, had grown to a height of 6 feet 8 inches, and was ready to take on the world. His first priorities were to modernize his military forces, and to gain coastal footholds for his navy on the Baltic, Black, and Caspian Seas. In an attempt to form alliances that might help Russia wrest some ports on the Black Sea from the Ottomans, Peter spent a year and a half touring western Europe. He tried to travel incognito among a large delegation of Russian officials, but his uncommon height gave him away, and he was disappointed that none of the monarchs he courted seemed as interested in subduing the Ottomans as he was. Nevertheless, Peter was able to learn much from his European hosts that would have a profound impact on his personal style and, by extension, the development of Russia.

Peter the Great by Étienne Falconet, erected in 1782. The pedestal, called the Thunder Stone, is reportedly the largest rock ever moved by humans

In 1703, Peter managed to seize control of a Swedish fortress on an island where the Neva River flows into the Gulf of Finland. Within a month, the czar had conscripted thousands of laborers to begin constructing the Peter and Paul fortress a few miles upriver. Instead of erecting a kremlin with tall towers, as was typical for medieval settlements, Peter ordered a fort with low bastions that were easier to defend with modern artillery. The new stronghold must have been formidable, because the Swedes never tried to retake their lost territory at the mouth of the Neva. Peter then hired a host of architects, engineers, shipbuilders, and skilled artisans from western Europe to help him build a new capital for the empire he envisioned—a city worthy of a new Caesar. He called it Saint Petersburg. Later regimes would adjust the name of the city as politics dictated. In 1914, when Russia wanted to distance itself from anything having to do with Germany (burg being German for castle), the city became known as Petrograd; when Bolshevik hero Vladimir Lenin died in 1924, the Soviets renamed the city Leningrad in his honor. Residents voted to restore the original name after the dissolution of the Soviet Union in 1991.

Peter and Paul Fortress, whose cathedral features the world’s tallest Orthodox steeple

A bronze statue of Minerva presides over the Academy of Fine Arts

Admiralty

The bus that picked us up outside the cruise ship terminal didn’t have to take us far to see some of Saint Petersburg’s most famous sights: the Winter Palace, which stretches 215 meters along the Neva; the Admiralty and the old naval shipyard; and the golden dome of St. Isaac’s Cathedral. On the other side of the river, we passed close by the Academy of Fine Arts; the bright-yellow Menshikov Palace, former home of Peter the Great’s most trusted friend; and the Kunstkamera, the museum Peter established to showcase his collection of “natural and human curiosities.” We got off the bus to take photos for a few minutes on the quay near the Stock Exchange and the Rostral Columns, two lighthouses that mark the point where the Neva River divides to go around Vasilyevsky Island.

Menshikov Palace

One of the Rostral Columns, decorated with sculptures representing the prows of captured ships

Sculpture of Neptune atop the Stock Exchange

Gardeners remove faded flowers from Exchange Square

Two monumental sphinxes on the quay were brought from Egypt in the 1830s

Artillery Museum

The bus took us back over the Neva, passing the Field of Mars, which has been variously used as a royal picnic area, zoo, and military parade ground; and the Summer Garden, which Peter the Great personally designed (with assistance from a French architect) to resemble the formal gardens he had seen at the palaces of European nobles. The Summer Garden featured the first sculptured fountains in Russia but, unfortunately, most of the original fountains were destroyed by a flood in 1777 and were never replaced. Marina told us that although that flood was bad, it wasn’t the worst Saint Petersburg has experienced. Truly catastrophic flooding occurred in 1724, 1824, and 1924, so many people are expecting the worst for 2024. Good thing we got here when we did.

St. Michael’s Castle

Just south of the Summer Gardens is St. Michael’s Castle, a palace built for Paul I, the son of Catherine the Great (more about her later), and completed at the beginning of the nineteenth century. Named for the patron saint of the royal family, the palace was built in the form of a medieval castle (albeit with classical styling) not only because Paul was captivated by the age of knights in shining armor, but also because he felt the need for a personal bastion of safety. He did not trust the members of his own court residing at the Winter Palace, apparently with good reason: forty days after he moved into his new home, a contingent of courtiers broke into Paul’s bedroom and, when he wouldn’t agree to abdicate, murdered him. St. Michael’s stood abandoned for two decades until it was turned over to the army for use as an engineering school. (Fyodor Dostoevesky was a student there.)

Church of the Savior on Spilled Blood

The shrine over the spot where Alexander II was assassinated

Iconostasis in the Church on Spilled Blood

Around the corner from St. Michael’s Castle is the Church of the Savior on Spilled Blood, built on the site where Alexander II, Paul I’s grandson, was fatally wounded by assassins in 1881. After he died a few days later, Alexander III announced that he would build a church on the spot as a monument to his father. The church’s elaborately decorated onion domes reflect the traditional Russian Orthodox style that Peter I and most of his successors had tried to get away from, so it really stands out among Saint Petersburg’s mostly classical- and baroque-style historic buildings.

Mosaics cover nearly every interior surface

The baptistry of the Church of the Savior on Spilled Blood is across the street

The interior is similarly ornate and colorful, with 7500 square meters of mosaic murals adorning its walls and ceilings. The Church of the Savior on Spilled Blood was not completed until 1907, during the reign of Nicholas II, and nearly suffered the same fate he did. The building was looted after the 1917 Revolution and, with no church organization to maintain it any more, was left to decay. During World War II (in the era when the city was known as Leningrad), it served as a temporary morgue for those who died either in battle or of starvation during the Nazi siege. Later, it was damaged by fire. After the war, what was left of the crumbling church became a warehouse.

Finally, in the 1970s, the property was entrusted to the same state institution that operated St. Isaac’s Cathedral Museum. (The Soviets, who shared Karl Marx’s view that “religion is the opiate of the people,” turned most of Russia’s major churches into museums; many of them never returned to their function as houses of worship.) Restoration of the Church of the Savior on Spilled Blood began in 1972 and was largely completed in 1996, although—as we could see from the scaffolding outside—repairs are still going on. Marina told us that the incredibly detailed mosaics were not assembled directly on the walls, but were created on panels in a studio and then transferred here. Also, because the church was built after the invention of electrical lighting, the original chandeliers were wired for electricity, and what look like stone benches along the walls are not seats, but enclosures for radiant heating units.

St. Isaac’s Cathedral

Our next stop was at St. Isaac’s Cathedral, which was commissioned by Alexander I in 1818 and took forty years to complete. Displays and models inside the church explain how it was constructed; the building was quite a marvel of engineering for the time. Because much of the ground in Saint Petersburg is marshy, 25,000 pylons were driven into the earth to provide foundational support for the massive structure, which was built on the site of four previous churches dedicated to Isaac (the saint on whose feast day Peter the Great had been born).

Exterior columns

The 48 portico columns at ground level are 17 meters tall and weigh 110 tons. More columns—a total of 112—surround the domes and windows on the upper levels; each was cut from a single block of red granite. An elaborate wooden scaffold was erected to set the columns in place, a process that took 45 minutes for each—which seems surprisingly short when you consider the magnitude of the job.

Model showing how the columns were put in place

Model of scaffolding used to erect the columns

A mosaic depicting the Last Supper, one of several mosaics made to replace deteriorating paintings

As with the Church of the Savior on Spilled Blood, the Bolsheviks initially removed most of the valuables from St. Isaac’s, but by 1931 the Soviet government had restored the building and reopened it as the Museum of Religious History and Atheism.

Interior of the dome

During World War II, the gold-plated dome was painted gray so that it would be harder to see from enemy aircraft. With the fall of the Soviet Union in 1991, religious activity and rites were reinstituted at St. Isaac’s. However, even though the governor of Saint Petersburg offered to return ownership of the property to the Russian Orthodox Church, the Church declined, so it remains mostly a museum. Regular religious services are held in a side chapel; the main nave is used for worship only on Christian holidays.

St. Isaac’s nave

The only stained-glass window in St. Isaac’s is behind the altar

Entrance doors fashioned after Ghiberti’s doors for the baptistry in Florence

Originally, the interior of St. Isaac’s had included many paintings by the best Russian artists of the nineteenth century. However, no provisions had been made for keeping Saint Petersburg’s cold, damp air from penetrating the church and causing irreparable damage to the canvases even before the building was completed. An attempt was made to reproduce the paintings in mosaic form, but the project proved too time-consuming and costly to continue. Many European cathedrals and American churches we have visited are decorated with stained glass, so we were surprised to realize that St. Isaac’s has only one such colored window. Marina explained that stained glass is not part of Russian religious tradition.

Repairmen on the roof of St. Isaacs were using a pulley to lift materials

The Winter Palace has not always been green and white, the Soviets’ preferred color for baroque buildings. Originally, it was yellow with gilt trim; during the 19th century, it was dull red

Back in the days when we were humanities students at Brigham Young University, our textbooks and the slide shows we saw in class sometimes included photos of paintings and sculptures from the Hermitage collection in Leningrad. Nancy figured that she would never have a chance to see any of those face-to-face, stuck as they were “behind the Iron Curtain.” Fast-forward 45 years: the Iron Curtain has been pulled open, Leningrad has become Saint Petersburg again, and today we went to the Hermitage Museum to see some of the world’s largest collection of paintings. (And to use the restrooms—Marina had not allowed us any opportunities all morning!)

Empress Elizabeth (1709-1762)

The Hermitage now comprises the entire Winter Palace, that long row of green-and-white buildings along the Neva River embankment where Peter the Great had decided to establish a new imperial residence. Peter died before his vision of a modern, westernized city was fully realized, but when his daughter Elizabeth became empress in 1741 (after ousting the latest in a series of ineffective successors to her father’s throne), she stepped up the pace of construction despite bitter weather and enormous cost. The lavishly decorated palace that Elizabeth had envisioned was finished shortly before she died in 1762.

Catherine the Great (1729-1796)

The Jordan Staircase derives its name from its use as the place from which the czar descended to the Neva River on Epiphany for a ceremony commemorating Christ’s baptism in the Jordan

But the Winter Palace wasn’t done. Within months of Elizabeth’s death, the German princess Elizabeth had chosen as a wife for her nephew and successor, Peter III, usurped the throne after her husband was murdered in a coup. Reigning as Catherine II for the next 34 years (and like Peter I, also known as “the Great”), she continued to expand the Winter Palace and extend the influence of western European culture within the Russian aristocracy. Again, construction went on and furnishings were purchased without regard to cost or inconvenience to anyone but Catherine and her select courtiers.

Small throne room

So where did the name “Hermitage” come from? Elizabeth had called her private apartment within the Winter Palace the “hermitage,” so Catherine adopted the name for a new, private wing where she could escape official duties and the formalities of court. In the process of furnishing the palace, Catherine authorized agents to purchase entire art collections from the estates of European noblemen.

The Return of the Prodigal Son, the last painting Rembrandt completed before his death in 1669

Catherine was particularly proud of a large group of paintings that had been intended for her rival, Frederick II of Prussia, because after a series of expensive wars against Russia, Frederick had been unable to come up with the cash to pay for them. Thus dozens of priceless canvases by Raphael, Veronese, Rembrandt, Rubens, Van Dyck, and other masters ended up on the walls of the Hermitage—to be seen only by Catherine and her closest friends.

The lady-in-waiting to Infanta Isabella in this portrait by Peter Paul Rubens may be the artist’s daughter

Roman Charity by Peter Paul Rubens, c. 1612, depicts a woman breastfeeding her imprisoned father

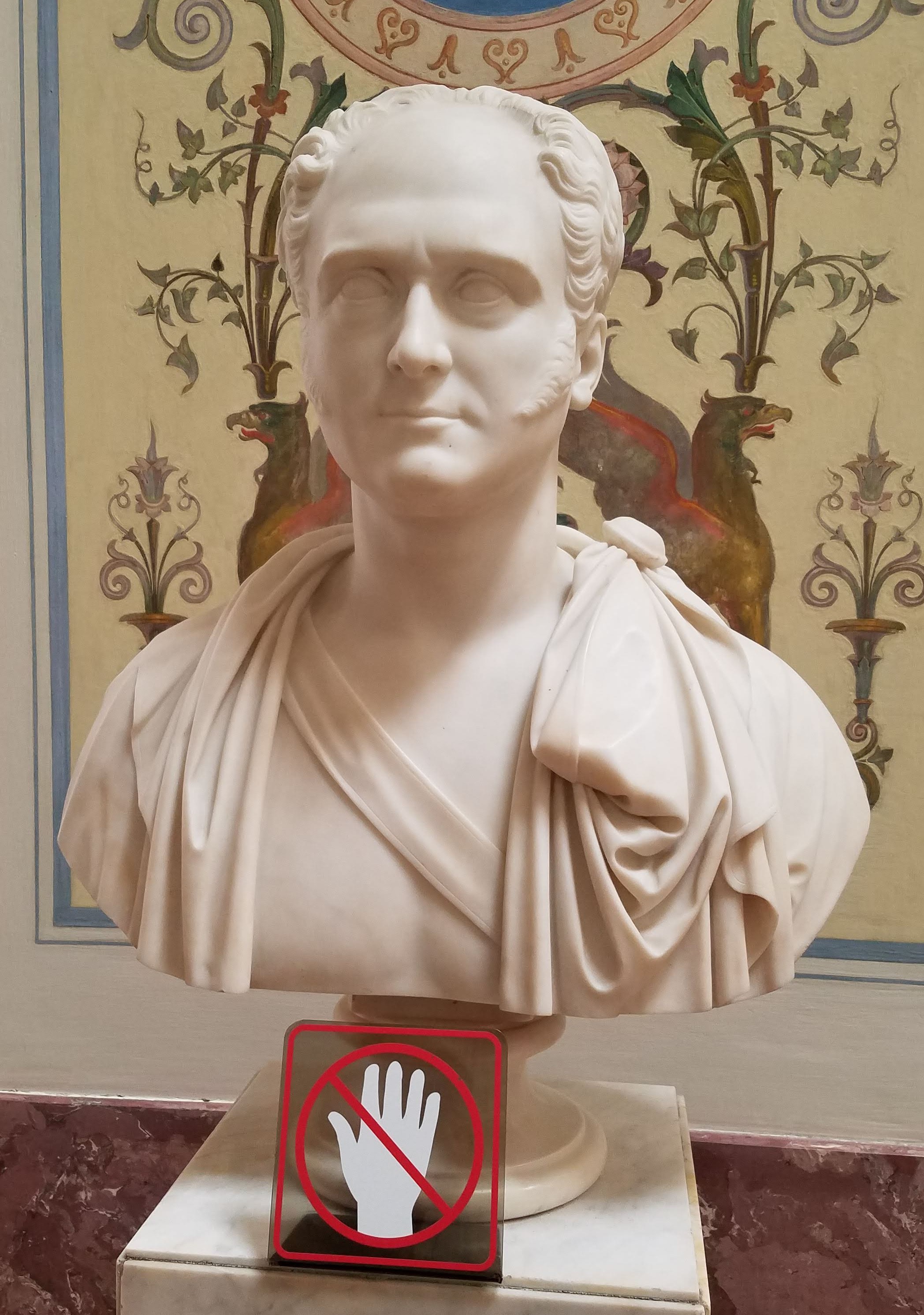

Alexander I (1777-1825) by Bertel Thorvaldsen

Catherine’s grandson Alexander I continued adding to the imperial art collection, notably by purchasing the collection of Joséphine, former empress of France and wife of Napoleon—who had plundered significant artworks from around Europe during his exploits.

The Revelers by Jan Steen, c. 1660, is a humorous self-portrait of the artist and his wife

After a devastating 1837 fire that destroyed the main part of the Winter Palace but not the Hermitage, Nicholas I, who had succeeded his brother Alexander, decided to create a museum where the huge art collection could be displayed. Moreover, he felt that the artwork should be available not only to the court but to the public. The New Hermitage opened in 1852, but the “public” allowed inside was somewhat limited by the fact that Nicholas demanded that all visitors wear formal evening attire no matter what the time of day.

The Raphael Loggia replicates the original in Rome’s Apostolic Palace

After would-be assassins exploded a bomb under the palace dining room in 1880, barely missing Czar Alexander II and his family, the Winter Palace fell out of favor as an imperial residence. Security concerns were an issue (another assassination attempt on Alexander II the following year succeeded), but later monarchs preferred more intimate dwellings in less “boggy” locations anyway. By 1900, the palace was used only occasionally for large state occasions, including the wedding of Nicholas II and Alexandra (a German princess said to be Queen Victoria’s favorite granddaughter).

Antiquities gallery ceiling in the Hermitage

After the initial revolution in February 1917 that effectively ended Russia’s monarchy, the Winter Palace became the seat of a provisional government, but that was not to last. The more radical Bolsheviks stormed the palace a few months later, threatening to destroy it. After forcing the provisional government to surrender, the revolutionaries spent five heady days ransacking the wine cellar and smashing furnishings, but ultimately realized that the palace contained treasures worth saving. The entire Winter Palace was declared part of the Hermitage Museum and, not long afterward, was opened to view by an amazed public (no formal dress required).

Roman mosaic table depicting Medusa and the Gorgon

Under the Soviets, the national art collection continued to expand, with pieces being moved from one museum to another throughout the country. The most important works in the Hermitage were evacuated from Leningrad during World War II, so even though the buildings sustained some bomb damage, the museum was able to reopen after the war. Since the end of the Soviet era, more and more visitors from all over the world have been able to experience the riches of the Hermitage.

Rembrandt, Danaë, c. 1636

The two hours we spent touring the museum today allowed us to see only a fraction of its vast, varied collection. Trying to take photos of the artwork was frustrating because of unavoidable lighting issues. The most valuable paintings are displayed behind glass—a precaution against further damage by the kind of lunatic who threw sulfuric acid on Rembrandt’s depiction of a nude Danaë in 1985 and then slashed the canvas with a knife—but we did the best we could to help us remember and share the highlights of what we had seen.

This is what an ancient Egyptian mummy looks like without its wrappings

Marina tells us about this gallery, which honors every Russian general who fought against Napoleon in the War of 1812

The Peacock Clock is a large automaton featuring three life-size mechanical birds

Paolo Uccello’s version of St. George rescuing a maiden from the dragon, c. 1460

As we followed Marina out of the Hermitage, we looked longingly at the signs pointing toward more galleries with more collections that we didn’t have time to see—but even former humanities majors have limits on how much art we can absorb in a single day. And this day was far from over.

The former Imperial Stables behind the Palace Embankment were the site of the soccer Fan Fest when Russia hosted the 2018 FIFA World Cup

About 4:00 p.m. the bus took us back to the Star Breeze, where Nancy did the day’s laundry while Michael napped, and then we changed into the nicest clothes we had brought before going upstairs about 5:20 to eat. Tonight, the ship offered an early dinner buffet to accommodate those of us who were attending performances in town tonight. Offerings included prime rib, kung pao chicken, and bread pudding laced with caramel sauce.

Last year, after we booked this cruise, Michael began checking events calendars for Saint Petersburg, hoping that the Kirov Ballet would be performing on the one night we would be here. The Kirov has set the international standard for ballet excellence for at least two hundred years, so to think that we might have a chance to see the famed company in its home theatre was thrilling—not just to us, but also to Tony and Katie, with whom we often attend the ballet in Cincinnati.

The first thing Michael discovered is that the Kirov Ballet is no longer known as the Kirov in Russia; that name was retired along with so many other Soviet-era appellations in the 1990s. (Sergey Kirov had been head of Leningrad’s Communist Party, so when he was assassinated in 1934 the Soviet State Theatre, Opera, and Ballet were renamed in his honor, even though he apparently did not have any particular interest in the arts.) Originally, the company had been the Imperial Russian Ballet, founded in Saint Petersburg in the 1740s to provide entertainment for the court. By the early 1800s, the troupe had developed into one of the best classical dance companies in the world, attracting the finest performers and most creative choreographers in addition to training new talent.

Mariinsky Theater

In 1860, the Imperial Russian Ballet moved into a new theatre named for its patron, Empress Maria Alexandrovna (wife of Alexander II), and took on the same name as the venue: the Mariinsky. This is the name by which the company is now known in Russia, even though the “Kirov” brand is still used abroad.

Once Michael figured out that the Mariinsky Ballet website he found online was the right website for the company we knew as the Kirov, he was able to determine (with help from our Russian-speaking son-in-law) that YES! there would be a performance tonight, and YES! good seats were available. Of course Katie and Tony wanted to come with us, and although it took a little time to convince some of the others that they really did not want to pass up this opportunity to see one of the world’s truly great ballet companies, eventually everyone in our group agreed to order tickets.

The Mariinsky Theatre was home to the imperial opera company as well as the ballet. Operas by renowned Russian composers Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky, Modest Mussorgsky, Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov, and Sergei Prokovfiev were presented on its stage, along with ballets such as La Bayadère, Swan Lake, and The Nutcracker. One of the lesser-known ballets that premiered there was The Bronze Horseman, with music composed in 1949 by Rheinhold Glière (a student of Alexander Borodin), based on a narrative poem by Alexander Pushkin. This was the ballet we were scheduled to see tonight; since we’d never heard of it before, we weren’t quite sure what to expect.

Mariinsky Theatre II

Tonight’s performance did not take place in the Mariinsky Theatre that opened in 1860; rather, we went to the Mariinsky II, a dazzling new theatre that opened in 2013. Based on a design by French architect Jean Nouvel, the lobby features a glowing onyx wall with glass stairs and walkways suspended from the ceiling; the sleek wood in the performance hall is accented with a hanging crystal sculpture that resembles a fountain of icicles.

Waiting next to the onyx wall to enter the theatre

Suspended staircase and walkways

Inside the theater with its three balconies

Waiting for the performance to begin

Alexander Pushkin (1799-1837)

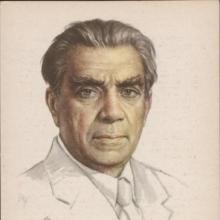

Reinhold Glière (1875-1956)

The Pushkin poem that inspired Glière’s ballet was itself inspired by the monumental equestrian statue of Peter the Great that stands in Saint Petersburg’s Senate Square. Written in 1833, the poem tells the story of a pair of young lovers caught in the devastating flood of 1824. The ballet begins with a carnival in Senate Square. After the jugglers and puppeteers have finished performing, Yevgeny and Parasha enjoy a private idyll on the green, beneath the shadow of the statue. Yevgeny tells Parasha about the great emperor, his prowess in battle, and the founding of Saint Petersburg; his tale is brought to life onstage by dozens of dancers in colorful period costumes, performing military marches and traditional Russian folk dances. In the second act, Parasha and her girlfriends have gathered outside her cottage on the shore of Vasilyevsky Island to celebrate her betrothal to Yevgeny, who secretly watches them dance while hiding behind a big willow tree. After he reveals himself, the girls congratulate the couple and then leave them alone so they can perform a romantic pas-de-deux. But then the sky suddenly darkens and torrents of rain begin to fall. Yevgeny must return to his home on the other side of the Neva before the bridges are washed away. Once there, however, as the storm continues to rage, he worries about his lover in her cottage by the shore. He decides to go out, hoping to save her from the rising river.

As Act III opens, the storm has passed, but the Neva has burst its banks and inundated much of the city. Yevgeny, finding no other way of crossing to Vasilyevsky Island to search for Parasha, plunges into the swollen river and swims across, but he discovers that the cottage has been swept away by the flood. The only thing that looks familiar is the battered willow tree. Driven mad by grief, Yevgeny returns to Senate Square and imagines that he sees Parasha dancing there again, but when she vanishes he turns to the statue of Peter I and angrily blames him for the loss of his beloved. After all, it was the emperor who chose to build the city so close to the river. Suddenly, the Bronze Horseman leaps from his pedestal and begins pursuing Yevgeny. The deranged young man turns to confront him and is trampled beneath the horse’s hooves.

But tragedy does not get the last word. In an epilogue, Saint Petersburg has been rebuilt—even better than before—and all its citizens (except Yevgeny and Parasha) live happily ever after.

Curtain call at the end of The Bronze Horseman

As is the case with most ballets, the story was secondary to the dancing, which tonight was masterful. As Yevgeny, Alexander Sergeev displayed an amazing combination of grace and vigor—especially considering that he was on stage for nearly the entire three hours. Yekaterina Osmolkina’s portrayal of Parasha captured both her vivacity and her vulnerability. Michael was wowed by the technical artistry of the six teenage boys who joined their older brethren in a series of Cossack dances in the first act, while Nancy loved the exquisite precision of the female corps de ballet in the second act. The Bronze Horseman was the perfect performance for us to see this evening, providing a unique review of Saint Petersburg’s history as well as a peerless introduction to classical ballet for those in our group who were experiencing it for the first time.

On the pier after the ballet

Towel creature of the night

It was still light outside when we left the theatre and got back on the bus about 10:30 p.m. The sky was streaked with pink and orange, and the Neva was calm. We took advantage of the opportunity for a magical photo on the pier, and then quickly went below to settle into bed, with visions of ballerinas dancing in our heads.

Oops, I hit send before I was done! It means so much to me that you loved the book! Good luck with your writing!