The view from our bedroom at Ørslev Kloster

Rain was coming down fairly steadily when we got up this morning. Notice that we said “got up” rather than “woke up,” a full night’s sleep still being too much to expect. Last night Michael was plagued by a headache, and Nancy often has trouble sleeping when the only available bedding was a down-filled duvet because it’s binary: either on or off, with no provision for incremental adjustments. We had tried to reset the radiators before we went to bed but weren’t sure exactly how to interpret the markings on the knobs, and it wasn’t until the middle of the night when it became obvious that we hadn’t turned them down far enough. In addition, even though we had put the cat out last night, we had failed to exile some other sleep-inhibiting creatures: mosquitos periodically announced their presence close to our ears. This morning, we moved cautiously in the bathroom to avoid disturbing a couple of little tormentors that had settled on the white curtains covering the window.

After we had finished our juice, bread, and yogurt and washed the dishes we had used, we got into the car and set off through the drizzle. Our first stop was at Højslev Kirke, the first of several tiny parish churches in the Nordfjends area on our itinerary today. Although the town of Højslev is only a few kilometers from Ørslev Kloster, it is a separate parish, serving maybe a hundred families. At least six pairs of Nancy’s Bertelsen forebears were married in Højslev Kirke, and many of them were later buried in the churchyard.

Højslev Kirke

When we began planning this trip, Nancy pictured visiting the burial places of her ancestors and taking photos of their grave markers, even though she knew the tombstones would be very old and most of the engravings worn away. Barely legible tombstones from the 1700s are not uncommon in old American cemeteries, however (photos of these abound on the Find a Grave website), so Nancy thought that she’d be able to locate at least a few of her Danish ancestors’ final resting places.

“I hate to tell you this,” warned her friend Kirsten, “but unless you have relatives that were buried within the past fifty years or so, you probably won’t be able to find any of their graves. Denmark is such a small country that they don’t have a lot of land to spare, so they tend to reuse the same plots in the churchyard over and over again. Especially if no one from the family is around to take care of them, the church will just remove the old markers to make room for new ones. There’s a chance you might find some old markers stacked together at the back of the cemetery, but don’t get your hopes up.”

“Really?” Nancy responded. “I had no idea. What do they do with the bodies in those burial plots, then? Do they move them, too?” Kirsten wasn’t sure–and said she wasn’t sure she wanted to know

Nancy wanted to know. Yesterday, when she asked Garry Keyes about this institutionalized grave-robbing, he corroborated Kirsten’s story. “The family leases the burial plot for a certain length of time–I think at Ørslev Kloster it’s thirty-five years–and then if no one renews the lease, the stones are removed and it becomes available for another family to use.”

“What happens to the remains? Are they moved, too?” Nancy asked.

“Hmm. That’s a good question,” Garry replied. “Maybe they dig deeper and rebury them under the newer caskets? I’m not sure.” (We’re still searching for a definitive answer.)

The churchyard surrounding Højslev Kirke is divided into tidy little memorial plots by low, neatly trimmed hedges, and most plots contain several engraved stones. Well-tended flowering plants abound. It’s the kind of graveyard Pinterest users would want to pin photos of on a “Quaint Memorial Gardens” board.

Interior of Højslev Kirke

The church itself, built of granite blocks, is about nine hundred years old–astonishing to consider that it’s been in constant use all this time, and that it has been so well maintained. A chapel was added in 1581 to house the tomb of the man who had owned all the land in the parish, and a few decorative features have been updated over the centuries, but the church probably looks pretty much the same as it did when Jens Pedersen Bertelsen and his bride, Mette Andersdatter, were married here 11 April 1735.

The altar in Højslev Kirke

Højslev Kirke pulpit

Several of Nancy’s ancestors were christened in Højslev’s baptistry

One of their descendants, Nancy’s great-grandmother Frederikka Kirstena Nielsdatter Bertelsen (known as “Stena”), was born in the village of Stårup, a few kilometers west of Højslev on the edge of the Skive Fjord. The local landowner, from whom the Bertelsen family rented the home they occupied and the land they farmed, lived in the Stårup Hovedgård (Manor House). A few months ago, Nancy had been excited to find the Stårup Hovedgård listed on the Visit Skive website among the “Manors and Monasteries” to see in the area. The site indicated that the manor house had been beautifully restored with period furnishings and was open to the public a few days a week. However, when she returned to that website later to find out whether the Manor would be open during our off-season visit, she couldn’t find it listed anymore, so she sent an inquiry. The reply was disappointing: Stårup Hovedgård had been sold to a new owner and was no longer open to the public. But there was hope: the tourist office representative who sent the reply provided the name and email address of the new owner, and suggested that Nancy contact her directly.

Nancy sent the owner a polite note explaining that her great-grandmother’s family had been tenants of the lord of Stårup Hovedgård in the mid-1800s, and that some of her relatives may even have worked as household servants on the estate. She was disappointed to learn that the manor house had been closed to visitors just as she was about to have the opportunity of traveling to see it. “We certainly don’t want to invade your privacy,” she wrote, “but would it be possible for my husband and me to at least visit the grounds of the estate?”

Nancy sent the owner a polite note explaining that her great-grandmother’s family had been tenants of the lord of Stårup Hovedgård in the mid-1800s, and that some of her relatives may even have worked as household servants on the estate. She was disappointed to learn that the manor house had been closed to visitors just as she was about to have the opportunity of traveling to see it. “We certainly don’t want to invade your privacy,” she wrote, “but would it be possible for my husband and me to at least visit the grounds of the estate?”

A few days later she received an equally polite reply: “You are welcome to visit the garden of the estate, and if we happen to be at home, the coffee is always hot.”

The sun began to shine through breaking clouds as we drove past furrowed fields and patches of woods toward Stårup Hovedgård. Google Maps led us to a driveway at the back of the manor house rather than the grand front entrance, which was just as well because the main drive was closed off by a big iron gate. Nancy had told the owner when to expect us, so although it felt a little strange to park in the private drive of someone we’d never met and start wandering through their yard, we had been invited to do so.

Stårup Hovedgård

House entrance

There was a car parked in front of the house, but no one emerged while we were walking around, and since it was still fairly early in the morning we decided not to knock. (We’re not coffee drinkers, anyway.) The house is large, but quite plain: basically a whitewashed rectangular box with a simple portico in the center of one side. The long drive and the L-shaped stables make it feel more manorial; if Pride and Prejudice had been set in Denmark, this could have been the Bennett home. What really distinguishes the place, however, is the moat: a grass-lined waterway about eight feet wide that surrounds the house and garden. It hardly looks like enough to stop an invading army, but probably helped to keep grazing cows and sheep away from the lady’s flower beds.

Entering these gates and walking up the long drive to the manor house must have made Nancy’s great-great-grandparents feel very small when they came to pay their rent

Looking across the moat toward the stables

All the fields beyond the moat once belonged to the Stårup estate

Wondering what the new owner might be keeping in the large stable building, we peeked through the windows. The spacious center section was empty except for a long bar with modern kitchen equipment along one end and some stacked tables and chairs. A smaller room next to it was entirely occupied with a curious contraption that Nancy initially thought might be one of those “Endless Swimming” lap pools, but which Michael identified as a brewing vat. Nancy recalled reading that the estate had included a café when the manor was open to the public, and Garry Keyes had mentioned a microbrewery next to Stårup Hovedgård that produced good craft beer, so this must have been it.

Having taken several photos of the estate and not wanting to overstay our welcome, we got back in the car and drove a few more kilometers toward an address that Nancy thought might be the home the Bertelsen family had been forced to abandon after they joined the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints in the mid-1850s.

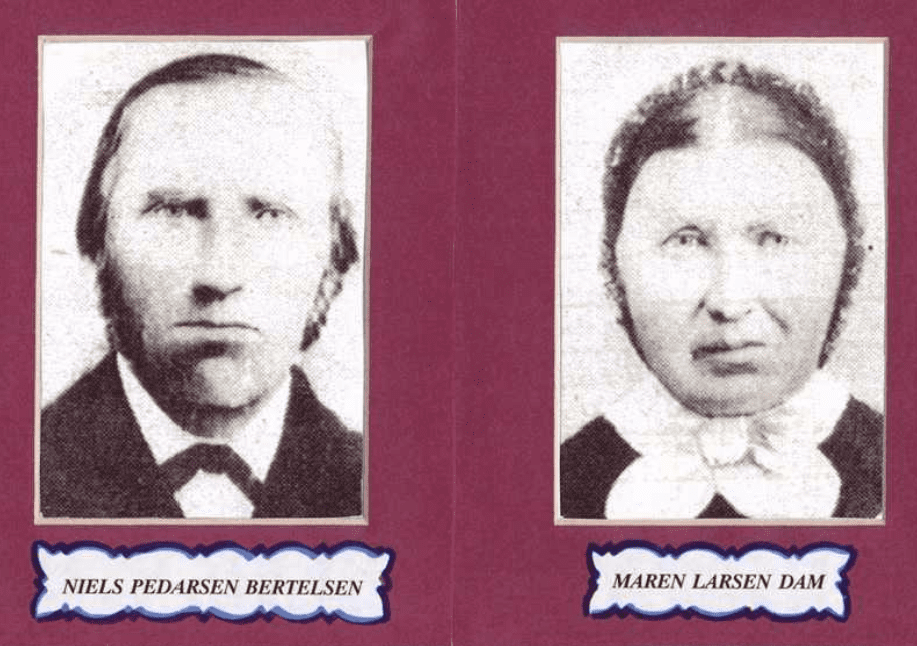

Nancy’s great-great-grandparents

According to family histories written by Nancy’s relatives, Mormon missionaries found eager listeners in the Bertelsen household when they arrived in the Nordfjends area in 1852. Most of the Stårup community was not so sympathetic, however. The Danish Constitution adopted in 1849 had established the Evangelical Lutheran Church as the country’s official, state-supported religion, so missionaries from a foreign sect must have been regarded with suspicion, and anyone who listened to them seen as unpatriotic. But Maren Larsdatter Dam Bertelsen (Nancy’s great-great-grandmother), an avid student of the Bible, immediately accepted what the Latter-day Saints taught as the word of God and wanted to be baptized by the authority of the priesthood they held. Her husband, Niels Pedersen Bertelsen, was not fully persuaded, but he continued to invite the missionaries to preach in their home and carefully considered what they had to say.

The Bertelsens soon found themselves not only ostracized but harassed by former friends. The older children, obliged by their family’s poverty to work as hired help for better-off neighbors, often returned home in the evening with their heels bruised and bleeding from having been kicked by their employers and others bent on punishing them for associating with heretics. One night, a mob surrounded the Bertelsen home and threatened to kill Niels along with the missionaries if they continued to preach there. When the lord of Stårup Hovedgård was informed that one of his tenants was hosting the missionaries, he gave Niels Bertelsen an ultimatum: Get rid of the Mormons, or get off my property. At that point (according to one of his grandsons), Niels figured that if this religion had the power to provoke such violent reactions from its enemies, then it must be true. Niels decided to be baptized. Within the next few months, all the Bertelsen children who were of age also chose to accept baptism into this new faith, despite the daily persecution that resulted. The family left Stårup, which had been their home for twenty years, and joined other Latter-day Saint converts in the Aalborg area until they could save enough money to emigrate to America.

Seven of the nine Bertelsen sisters as they appeared about 1910. Nancy’s great-grandmother Stena is at the far left, back row. The family also included one brother.

Today, Nancy hoped to be able to locate the Bertelsens’ former home, or at least the place where it once stood. Family records show that Stena Bertelsen and eight of her nine siblings had been born at a place called Skræpperhus in Højslev Parish. Nothing by that name–which Google translates into English as “Squawk House”–appeared on Google Maps until Nancy zoomed about as far as possible into the Stårup area, and a marker for what appears to be a small business called Skræpperodde popped up. With further investigation, she was able to determine that Skræpperodde (Squawk Isthmus) must be some sort of small land-and-livestock management firm, but she couldn’t find any contact information other than the address. With such a unique name in such a small locale, however, the property was certain to have a close connection to the place where her forebears had lived. Nancy put the address on our itinerary so we could at least drive by.

The terrain in Nordfjends is mostly flat and probably only a few meters above sea level even at its highest points. Most of the land is tillage: fertile fields outlined by hedgerows and narrow lanes, with small clusters of farm houses huddled around the points where roads meet. Neat rows of small fir trees march across some of the larger plots: Christmas tree farms. As we drove from Stårup Hovedgård toward the address on Pallesdamvej (Low Pond Way), we glimpsed sunshine reflecting off the water of Skive Fjord, just beyond the trees.

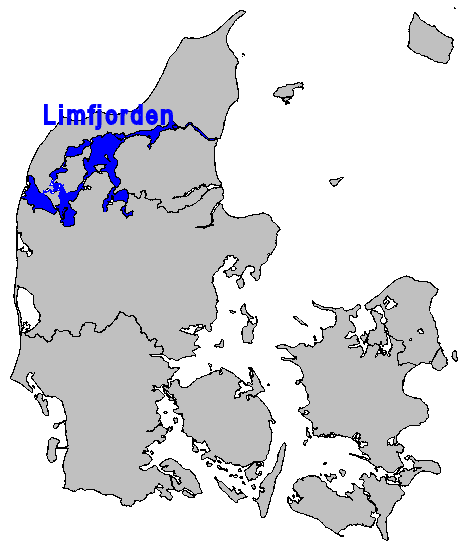

The Limfjord sprawls across northern Jutland

A word about fjords here. Merriam-Webster defines a fjord as “a narrow inlet of the sea between cliffs or steep hills or mountains.” Well, either the Danes did not consult Merriam-Webster, or neither Mr. Merriam nor Mr. Webster ever visited Denmark, because there are no cliffs, steep hills, or mountains around the narrow inlets of the sea here. Denmark’s Limfjord, which sprawls across the northern part of Jutland, actually comprises several interconnecting fjords that each has its own name. Viking sailors appreciated these waters because they could accommodate their shallow-draft ships but wouldn’t allow the deeper-hulled vessels of their enemies to follow them home. Fishermen appreciate the abundant catches they still haul from the brackish water.

“You have arrived,” announced the voice of our GPS. On both sides of the road were tall green hedges, but over the top of the one on our left we could see the slate roof and dormer windows of an old but well-maintained house and barn. Some of the architectural details looked very much like those we’ve seen on the pioneer-era houses in central Utah that were built by Danish immigrants: a high peaked roof, and arched windows topped with simple but distinctive decorative brickwork. Nancy found a break in the hedge and snapped a photo of the place, which fits the description of the Bertelsen home given in several family histories. We can’t prove that this is the house where Nancy’s great-grandmother was born, but it certainly looks like it could be.*

“You have arrived,” announced the voice of our GPS. On both sides of the road were tall green hedges, but over the top of the one on our left we could see the slate roof and dormer windows of an old but well-maintained house and barn. Some of the architectural details looked very much like those we’ve seen on the pioneer-era houses in central Utah that were built by Danish immigrants: a high peaked roof, and arched windows topped with simple but distinctive decorative brickwork. Nancy found a break in the hedge and snapped a photo of the place, which fits the description of the Bertelsen home given in several family histories. We can’t prove that this is the house where Nancy’s great-grandmother was born, but it certainly looks like it could be.*

Could this house at the intersection of Pallesdamvej and Stårupvej, about half a mile from Skive Fjord, be the “Skræpperhus” where Nancy’s great-grandmother and her siblings were born?*

*Several months after we published this blog post in 2017, we were surprised to find a comment left by a descendant of the branch of the Bertelsen family that had remained in Denmark. Knud told us that one of his relatives had googled Skræpperhus while trying to learn more about the location and history of the Niels Bertelsen family’s home, and had been led to this page. Through this connection, Nancy learned that the house she had photographed is not the one her great-great-grandparents had lived in. The actual Skræpperhus was a much humbler dwelling, with a thatched roof and only two rooms–one for the humans and one for the animals. The cottage no longer stands, but Knud sent copies of some nineteenth-century maps showing exactly where it had been located, about 300 meters north of the house in the photo above.

Staarup Gaard topographical map

From Stårup we turned north toward the village of Lundø, located on a T-shaped peninsula that reaches into the southern arm of Limfjord like a shower squeegee. Today Lundø is a beach resort with a few shops and cafés catering to visitors who rent cabins or campsites along the shore, but in the past it must have been a thriving community of farmers and fishermen. Both Niels Bertelsen and his wife Maren Dam had grown up in Lundø, as had their parents and grandparents and probably more generations back. At least a dozen of Nancy’s ancestors were buried in Lundø’s churchyard, but of course we couldn’t find any markers bearing their names.

Lundø Kirke was built in the mid-1300s

Lundø Kirke pulpit

This finely carved oak Madonna dates from the 1400s

Interior of Lundø Kirke

Queen Louise painted the figure of Christ above the altar to replace a medieval crucifix that was moved from Lundø Kirke to the National Museum in the 1880s

Children’s activity bags hanging just inside the entrance to Lundø Kirke testify that at least a few families regularly attend this tiny parish church

One of the butikker in Lundø had an åben sign posted, so we decided to stop and see what they had for sale. We had to ring a bell to get in, and once we entered, we realized that the shop was set up in a couple of large rooms built onto the front of the proprietor’s home. Most of the merchandise consisted of handknitted Nordic-style sweaters, with a limited selection of leather goods, local pottery, and linens. We found a handwoven table runner that we really liked, and Michael also considered buying a knitted cap until we were told that the shop could not accept our credit cards. Alas, we had not yet obtained any Danish kroner and the nearest ATM was back in Højslev, so we were unable to make a purchase.

Limfjord, as seen from Lundø

Since it was nearing lunchtime, we drove into Skive and headed for a bakery-café recommended by TripAdvisor: En Bid af Himlen (A Bite of Heaven). The aroma inside was indeed heavenly: cinnamon, nutmeg, and baking butter. The young woman at the counter where we were supposed to order tried to be friendly and helpful, but spoke only a little English and the menu on the chalkboard was written only in Danish, so the girl had to get her manager to help us. The manager apologized for the lack of a printed English menu, explaining that they had just changed their bill of fare for the fall and their English translator hadn’t had a chance to work on it yet.

Inside En Bid af Himlen

We had more than a few “bites of heaven”

There weren’t that many choices, and everything the manager described sounded really good, so we probably could have just pointed randomly at a couple of items and been totally satisfied. We shared the salad of the day–farro with curried chicken, bacon curls, diced pineapple, cucumber balls, and curried green tomato wedges atop mixed greens–and a vegetarian sampler plate composed of falafel balls, pot cheese, a wedge of quiche, and a small vegetable-stuffed pastry surrounding a bed of shredded cabbage, pumpkin seeds, and pan-roasted chickpeas that were so amazing, Michael was motivated to go back to the kitchen and ask the cook to show him how she had prepared them. We also shared a delectable little “Black Magic” cake.

We didn’t get to enjoy this meal right away, however, because when we tried to pay for what we had ordered, the café’s card reader wouldn’t accept anything in our wallets. We still had no cash, so we had to walk around the corner to a bank on the town square to get some. We waited while a woman already at the ATM completed her transaction, and then when she heard us speaking English, she stayed to make sure we didn’t have any trouble navigating through the Danish prompts on the screen. She went into the bank, then returned a moment later to say, “May I give you some small advice? Be sure to get small notes–fifty kroner or less–because most of the shops around here don’t use much cash and will not be able to give you change for big notes.” We did get some big notes, however, since we planned to pay cash for our stay at Ørslev Kloster because the monastery-retreat center wasn’t equipped to take credit cards, either. Garry Keyes had explained that most daily financial transactions in Denmark are accomplished by direct bank transfers through smartphones–which most of us benighted Americans can’t do yet. Garry didn’t seem too worried about how we were going to pay for our room (and the use of the linens, which is extra), saying, “We’ll work something out when you leave, or when you get back to the States,” but we decided that handing over some cash would be the least complicated method for everyone–as long as Garry didn’t have to make change.

Skive’s town hall (center) on the main square

Now able to pay for our order, we went back to the café and ate our delicious lunch. While we were eating, we noticed that the counter girl was being closely but kindly supervised by another young woman. The manager had mentioned that some of the workers at En Bid af Himlen were student interns, and that this was the counter girl’s first day on the job. What we didn’t learn until later, when we told Garry where we had eaten lunch, is that the café’s interns are not simply students learning the food service trade, but students with learning disabilities that the café helps to train. The people who operate “A Bite of Heaven” must truly be angels.

En Bid af Himlen is on a side street near the town square

En Bid af Himlen is located on a narrow side street with no on-street parking, so we had parked in a public lot nearby. We hoped that we had correctly interpreted signs that appeared to say that we could park free for two hours. When we returned to the lot, Michael noticed that all the other cars parked there had little cards with numbered dials on them behind their windshields.

A meter for free parking

“Oh, that’s what that card is for!” he said. When he unlocked our Peugeot, he pulled a similar card out of bin in the driver’s door. “I guess you’re supposed to move the dial to show what time you parked, and put the card in your windshield.” A good system for a society of honest people.

The total at gas pumps that measure liters is always disconcerting no matter what currency they use, but the cost in kroner is particularly shocking

Entrance to Fyrkat

After filling up our gas tank, we drove east on a “red road” for about forty-five minutes to reach Fyrkat, the site of an ancient ring fortress built by Harald Bluetooth in 980 AD. We had no trouble finding the nearby re-creation of a tenth-century Viking village, which we knew would be closed this week, but we had to ask directions to locate the remains of the ring fortress on a hill overlooking the Mariager Fjord. We knew that the indoor exhibits at the ring fortress would be closed, too, but we had been told that we could still walk around the site and read the information placards.

The original ring fortress at Fyrkat enclosed sixteen of these long houses, arranged like wheel spokes. This one was reconstructed in 1985

We were the only visitors at Fyrkat this afternoon, but we weren’t alone: that’s a flock of grazing sheep in the background. The dots in the grass indicate where the wooden posts of the long houses once stood

The museum buildings at Fyrkat were closed, but we could walk around outside. The distinctive yellow-gold and reddish colors of many old structures here in Denmark result from the addition of iron oxide to a basic whitewash mixture. The compound helps to prevent the growth of mold and moss–a necessity in this cool, damp climate

The Fyrkat complex includes a mill (built much later than the 10th century, but still old)

The mill works

Steps up to the road are made of old mill stones

Vikingecenter Fyrkat is a living-history museum of 10th-century life (when it’s open)

On our way back to Ørslev Kloster this afternoon, we stopped at Ørum Kirke in the parish just to the east of the monasterial estate. The church doors were locked, and even though Nancy attempted to gain entrance by climbing up an exterior ladder and crawling into the attic, we were unable to get into the chapel where yet another pair of her fourth- or fifth-great-grandparents were married on 23 June 1726–exactly 251 years before our own wedding day. (It occurred to us that the union of Peder Johansen and Johanna Pedersdatter must have resulted in even more nomenclatural confusion than usual.)

Ørum Kirke

Nancy climbed the ladder at the back of the church, but there was no passage from the dusty attic into the chapel. She decided not to try ascending another ladder into the belfry

Looking east from Ørum toward a lower arm of Limfjord

Ørslev Kloster was only a few minutes away and sunset still a couple of hours off, so we borrowed some “wellies” and spent the remainder of the afternoon exploring a trail that took us through the woods and pastures behind the monastery, the cemetery, and more of the building itself.

Ørslev Kloster from the rear

A footpath behind the monastery

Fields of feed corn will provide winter silage for the estate’s livestock

A stile allows people to enter and leave the pasture without being followed by the sheep

The Ørslev Kloster estate has a pasture for sheep on one side and a pasture for cows on the other

The monastery’s rhubarb patch

The vineyard

Michael climbs from the garden toward the cemetery

Ørslev Klosters cemetery

Old grave markers are removed from private plots after the lease period expires and get clumped together at the back of the cemetery. We’ve read that Denmark’s discarded memorial stones often get pulverized and used for roadbeds

Ørslev Kloster’s stone “beehive”

We were sure the stone “beehive” outside Ørslev Kloster–as well as several others we’ve seen in the Nordfjends area–must have some cosmic significance, until Garry Keyes explained that the building of such cairns has become a popular art project for students and other youth groups in recent years. “They’re just for fun,” he said.

Michael was pleased to find a book of Bartok’s Romanian Dances on the piano in the monastery’s dining room. The portrait over the side board is of Countess Olga Sponneck, who restored the estate

The monastery’s library

Since we plan to leave Ørslev Kloster very early tomorrow, we needed to find Garry this evening so we could pay him (in cash) for our stay, but another resident told us that he had already gone home. Initially, we had assumed that Garry and his wife lived on the estate, but then we learned that they live in their own house in nearby Højslev. We obtained the address and arranged to stop on our way to dinner at Højslev Kro (Inn).

The Keyes home is much more modern and much less austere than the monastery. Garry told us that he and his wife had bought an old farmhouse (“Property is dirt cheap around here,” he said), updated the kitchen and living room, and then converted the adjacent barn into more living space for their growing family. As we talked, we had a chance to meet all three of Garry’s young daughters, but unfortunately we didn’t get to meet his wife–a cellist–because she was rehearsing with a local string ensemble. It was fun for us to get a sense of daily twenty-first-century life in a normal Danish household after a couple of days seeking greater understanding of the past.

Højslev Kro

Højslev Kro glowed yellow in the twilight as we pulled into the parking lot. Garry had recommended the restaurant here and TripAdvisor had offered a concurring opinion. The kitchen is run by a husband-and-wife team, and the menu reflects the fact that he is Danish and she is from Thailand. Michael decided to order the Thai beef with vegetables, rice, and a stuffed pancake; Nancy chose the recommended special: tenderloin of local beef, which came surrounded by braised vegetables (including a Jerusalem artichoke, a parsnip, and an onion), a parsley croquette, a tender zucchini dumpling, and a pile of sautéed morels. After consuming all the sides and about half the meat, Nancy was too full for dessert, but Michael thought he could handle an assortment of ice creams that included mango, fig, and vanilla topped with an exotic Chinese cherry.

Højslev Kro glowed yellow in the twilight as we pulled into the parking lot. Garry had recommended the restaurant here and TripAdvisor had offered a concurring opinion. The kitchen is run by a husband-and-wife team, and the menu reflects the fact that he is Danish and she is from Thailand. Michael decided to order the Thai beef with vegetables, rice, and a stuffed pancake; Nancy chose the recommended special: tenderloin of local beef, which came surrounded by braised vegetables (including a Jerusalem artichoke, a parsnip, and an onion), a parsley croquette, a tender zucchini dumpling, and a pile of sautéed morels. After consuming all the sides and about half the meat, Nancy was too full for dessert, but Michael thought he could handle an assortment of ice creams that included mango, fig, and vanilla topped with an exotic Chinese cherry.

Tonight we were not the only diners in the restaurant. A table on the other side of the room was occupied by four men who were enjoying the Danish beef and a lot of wine. Their conversation carried easily across the empty tables, and although they were speaking Danish, we could tell they were talking business because every now and then we could hear English words or phrases that must be familiar to corporate-types everywhere: sustainability, synergy, global strategy, downsize. They were still talking when we finished our meal and left.

Tonight we were not the only diners in the restaurant. A table on the other side of the room was occupied by four men who were enjoying the Danish beef and a lot of wine. Their conversation carried easily across the empty tables, and although they were speaking Danish, we could tell they were talking business because every now and then we could hear English words or phrases that must be familiar to corporate-types everywhere: sustainability, synergy, global strategy, downsize. They were still talking when we finished our meal and left.

Back at Ørslev Kloster, we listened to a few more LDS Conference speakers before we turned down the heat and went to bed.

Hello Nancy,

I have a friend in Denmark who is also trying to help me locate the “little white cottage” location in Skræpperhus. He sent me this link. https://www.dingeo.dk/adresse/7840-h%C3%B8jslev/pallesdamvej-18/foto/. Is this the one you were using to find it on Pallesdanvej? Or do you thing they built it on the site of the real location?

A map showing the location of Skræpperhus is available here: https://www.familysearch.org/photos/artifacts/88222581?p=24306818&returnLabel=Niels%20Pedersen%20Bertelsen%20(KNC1-447)&returnUrl=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.familysearch.org%2Ftree%2Fperson%2Fmemories%2FKNC1-447

Hello, cousins all,

I also come through Christianna Dorthea Bertelsen. I loved this article because we are leaving in 3 weeks to discover exactly what you were looking for, our Bertelsen heritage sites. I have met many of our relatives from the 10 children of Niels and Maren. We met in 2008 around his 200th birthday and added a plaque on the back of his gravestone in Mount Pleasant, Utah.. It has the names and dates of all of his 10 children on it. I will try to figure out how to add a picture of two of it.

I did go to Denmark in 2006 and try to put things together, but now I have so much more to go on. Thank you so much for this blog. It is just what I needed.

Many Thanks,

Renee

renee@fyans.com

I’m glad that you found the record of our experiences helpful and hope you have as marvelous a time in Denmark as we did! We just returned from a brief visit to Copenhagen, where we met Knud, a descendant of Niels Bertelsen’s older brother Peder. He has provided much more information about the lines of the family who remained in Denmark rather than emigrating the the U.S. He is trying to discover more about our common ancestors from local records that have not yet been digitized.

Dear Nancy,

Thanks for your reply to my comment, I would love to get more information from you or Knud. I’ve tried to reach out to him via the email he left above but have not heard back. Is there any way you could have him contact me? Thank you!

Thank you for your kind reply. I have tried to contact Knud for more information about the Skræpperhus and Lundø area but haven’t heard from him yet. I used the e-mail he posted, but perhaps my inquiry went to his Junk box. Is there anyway you could contact him and give him my e-mail address? I would appreciate it very much.

Which of the 9 sisters do you come through from Niels and Maren? Were they from Summit where Maren is buried?

Thanks so much for your help. It is great to hear from new cousins.

Niels and Maren’s sixth child, Frederikke Kirstine, was my great-grandmother. She emigrated to America in 1862, and in 1864, she became the plural wife of Soren Larsen, who was 20 years her senior and lived in Spring City, Utah. She remained in Spring City after Soren’s death, but her happiest days were spent visiting her sisters in Mount Pleasant.

Hello,

Maren Larsdatter Dam Bertelsen and Niels Pedersen Bertelsen are my 4th great grandparents threw their daughter Christiana “Annie” Dorthea Bertelsen. I have really enjoyed reading your post, How excited it must have been to see all this! Trip of a lifetime! Would it be okay if I also seen the information Knud mentioned above? So I guess that would make you, Knud and I all distant cousins?

-Billie

billie.m@hotmail.com

Dear Nancy and Michael.

My name is Knud Mørk Hansen, and I am living in Albertslund near Copen-

hagen. I am a decendant of Peder Pedersen Bertelsen, who is a brother to

your Niels Bertelsen from Skræpperhus in Stårup. I have worked with family

history research for many years. I can send you a lot of information about

Skræpperhus and Skræpperne, but I need more space than this little window.

If you are interested, please send me your e-mail address.

Yours sincerely, Knud Mørk Hansen. My email: knudmh@comxnet.dk