Hotel Barceló

Having only partially adjusted to the Central European Time Zone, both of us woke up early and had showered, dressed, and mostly repacked by the time the breakfast buffet opened in the Hotel Barceló’s sleekly modern dining room. It was a nice spread: like most European breakfast buffets, it included cold cuts and vegetables in addition to the usual selection of cereals, pastries, yogurt, fruit, eggs, bacon, sausage, baked beans, and potato patties. Notable extras included some unexpectedly spicy cheese meatballs, tortilla Española (Spanish-style potato omelet), and three flavors of honey that you could dispense into tiny edible wafer cups. There also was a tray of fresh honeycomb to smear onto your choice of many types of bread. We were amply fed when we returned to our room.

The Avis/Budget agency at the train station does not open until 9:30 a.m. on Sundays, so we had nearly an hour to kill before we could walk over and pick up our rental car. Since the LDS Church is holding its semiannual General Conference this weekend and sessions had begun yesterday while we were flying over the Atlantic, we downloaded the talks that were already available over the Internet and listened to a few of them before checking out of the hotel. We appreciated President Uchtdorf’s talk about turning to the Lord, and Bonnie Oscarson’s call to remember that those who most need our service may not live only in areas devastated by disaster, but rather, in our own neighborhoods or even our own homes.

But today we are far from our own neighborhood, and thankfully, not in a disaster area. It’s raining, but only lightly and intermittently. We continue to pray for those in dire need across the world, and will look for ways to serve whoever crosses our path in the coming days.

With suitcases in tow, we walked the half-mile back to the train station and located the Avis agency. Although it was 9:35, the door was locked. The remnants of Michael’s high school German allowed him to decipher a sign on the door indicating that the proprietor would return “in a few minutes,” but it was another fifteen or twenty before someone finally arrived to let us in. By then some other customers had gathered outside the door, and when it became obvious that the man behind the counter was set to dispel the stereotypical notion that all Germans work efficiently, we were very glad that we had been the first in line. Because we had a 1:30 lunch reservation at a restaurant a least three hours away from Hamburg, and we weren’t sure what to expect at the border crossing from Germany into Denmark, we had hoped to be in the car and on the road by 10:00, but we didn’t get out of the agency office until about 10:15.

Our Peugeot 2008 Hybrid

Our assigned Peugeot 2008 was parked in a garage across the street. We located it, loaded our luggage, typed the address of our lunch destination into Google Maps, and started out. At least, we tried to start out, but every time Michael took his foot off the gas, the engine stalled. We were puzzled and dismayed until the mental light finally went on: the Peugeot is a hybrid. The unexpected silence whenever we stopped to wait for a light was disconcerting, but eventually we got used to it.

Michael was wise to have downloaded Google Maps onto his phone, because even though the Peugeot came equipped with GPS we never figured out how to get directions in English. Even with commands in a language we could understand, navigating through traffic in a large, unfamiliar city was nerve-wracking. Once on the autobahn we could relax a bit, though we had to share the road with a lot of trucks that seemed much too big for European roads, normal-size sedans with multiple bicycles hung on the back, and a surprising number of cars towing camping trailers. Michael, who was driving, observed that in contrast with most American drivers who like traveling in the fast lane, their European counterparts generally were willing to adjust their own speed to accommodate those on the right who needed to pass. We also noted that Europeans are much better at using the full length of both lanes during a merge.

About 75 km out of Hamburg, we encountered a major slowdown. A two-tone siren heralded the approach of a Polizei car from behind, then an ambulance, and then another. Soon we could see signs of an accident in the middle of the road ahead—inconveniently located, but apparently not too serious. Luckily, there was a rest area exit just at the point where the collision had occurred so traffic could be routed off the highway and around the wreckage, but we were dismayed to find that the backup persisted on the other side. About 10km and forty minutes later, we finally encountered the source of the problem: construction on the bridge over the Nord-Ostsee Kanal had constricted passage to only one lane in either direction. Once over the bridge, we could resume normal speed at last. The guards at the border crossing simply waved us through, so we were able to reach the exit for Jelling, Denmark, a little after 2:00 p.m. We hoped a late arrival would not prevent us from getting a table so we could enjoy the frøkostbord (lunch buffet) at the Hopballe Mølle (Mill).

Hopballe had been listed on FamilySearch as the seventeenth-century birthplace of Peder Christensen and his wife Johanne Nielsdatter, some of the deepest roots traced thus far on Nancy’s family tree. A few of the men associated with this line (forebears of her great-grandfather Søren Larsen) are surnamed Møller (Miller). Several weeks ago, when Nancy zoomed way into Google Maps to try to locate Hopballe, she found no town, but rather a short country road called Hopballevej (vej = way, pronounced “vie”) between the town of Jelling and the village of Vindelev, where succeeding generations of her family had lived. A regular Google search produced hits for the website of a farm-to-table restaurant and reception center named Hopballe Mølle, currently operating in a historic mill. It seemed too good to be true! Elated to discover not only the restaurant’s existence but also that it would be open for weekend buffets during October, Nancy determined how to fit a visit into our itinerary and then reserved a table.

Getting off the “red road” that led into Jelling, we followed a narrow “yellow road” over green hills and through patches of woods, laughing each time we approached an intersection because, had Michael literally obeyed GPS commands to “continue straight,” in each instance the car would have plowed into a cultivated field, a cow pasture, or a tree. Soon, we were directed through a succession of turns on barely paved “white roads” not much wider than the Peugeot. Occasionally, we passed a lane leading toward an ancient farmhouse or a mossy-roofed barn. The sun had begun to stream through dispersing clouds, and the scenery could not have been more perfectly bucolic.

“Is this the way we’re going to be spending the next few days?” Michael asked. “If so,” he went on, “I’m going to love it!”

Crossing a brook and rounding a bend, we caught a glimpse of a glassy pond, and then a group of tidy red-brick buildings: Hopballe Mølle. Nancy could hardly hold back tears as we parked and got out of the car, realizing that her forebears had once called this impossibly lovely place home.

Hopballe Mølle

Frøkostbord at Hopballe Mølle

The restaurant hostess led us past a long bord filled with platters of roast chicken, little potatoes flecked with herbs, heirloom tomatoes, and other fresh farm fare toward a table in a sunny, glass-enclosed room overlooking the millpond. Picking up plates, we discovered a variety of cold salads on the other side of the bord, and side tables featuring breads, cheeses, and fresh fruit–including stems of bright red lingonberries. It wasn’t easy to save room for dessert, but we had seen Hopballe’s signature kagebord (cake table) at the far end of the serving room and didn’t want to miss it. The viola-decorated cream cake and the rhubarb crisp were especially tasty.

The brødbord

The kagebord

The restaurant and event center overlooks the mill pond

Knowing we’d need to either provide our own breakfast for tomorrow morning or eat at the Danish equivalent of Denny’s, we picked up half a loaf of multigrain bread from the buffet and purchased a jar of rhubarb jam from the mill’s store before saying goodbye. On the way out of the restaurant, Nancy noticed a couple of framed photos on a post near the register: an old man and an old woman in sepia tones. The hostess followed her gaze and said, “They’re the owner’s great-grandparents. This farm has been in his family for six generations.”

Nancy said, “Some of my ancestors may have been the millers here back in the 1600s.”

“Really?” she asked. “What were their names?”

Nancy laughed and shrugged her shoulders. “Peder. Peder Christensen. And Niels–I don’t know what surname he may have gone by. They lived a very long time ago.”

The old mill at Hopballe

The Hopballe Mølle complex includes a working farm that supplies food for the restaurant

Ten minutes over the winding roads took us from the mill into the town of Jelling. Seven hundred years before Peder Christensen and Johanne Nielsdatter were born in Hopballe, a Viking chieftain named Gorm the Old established a stronghold in Jelling and persuaded the leaders of other Viking bands (forcefully, no doubt) to form an alliance. Thus Gorm became the first king of Denmark. Gorm’s son, Harald Bluetooth, is celebrated not only for building more strongholds across Jutland and cementing the royal line that continues today, but also for converting to Christianity about 965 A.D. Many Vikings had already become Christianized by the tenth century, so Harald’s decision to accept baptism probably was more a political expediency than a true spiritual conversion, but the fact that Denmark officially became a Christian nation helped to protect the land against conquest by the German rulers of the Holy Roman Empire and to bolster the power of the new Danish monarchy.

Michael climbs the Viking burial mound in Jelling

View of a cemetery with more recent memorials from the top of the Viking burial mound

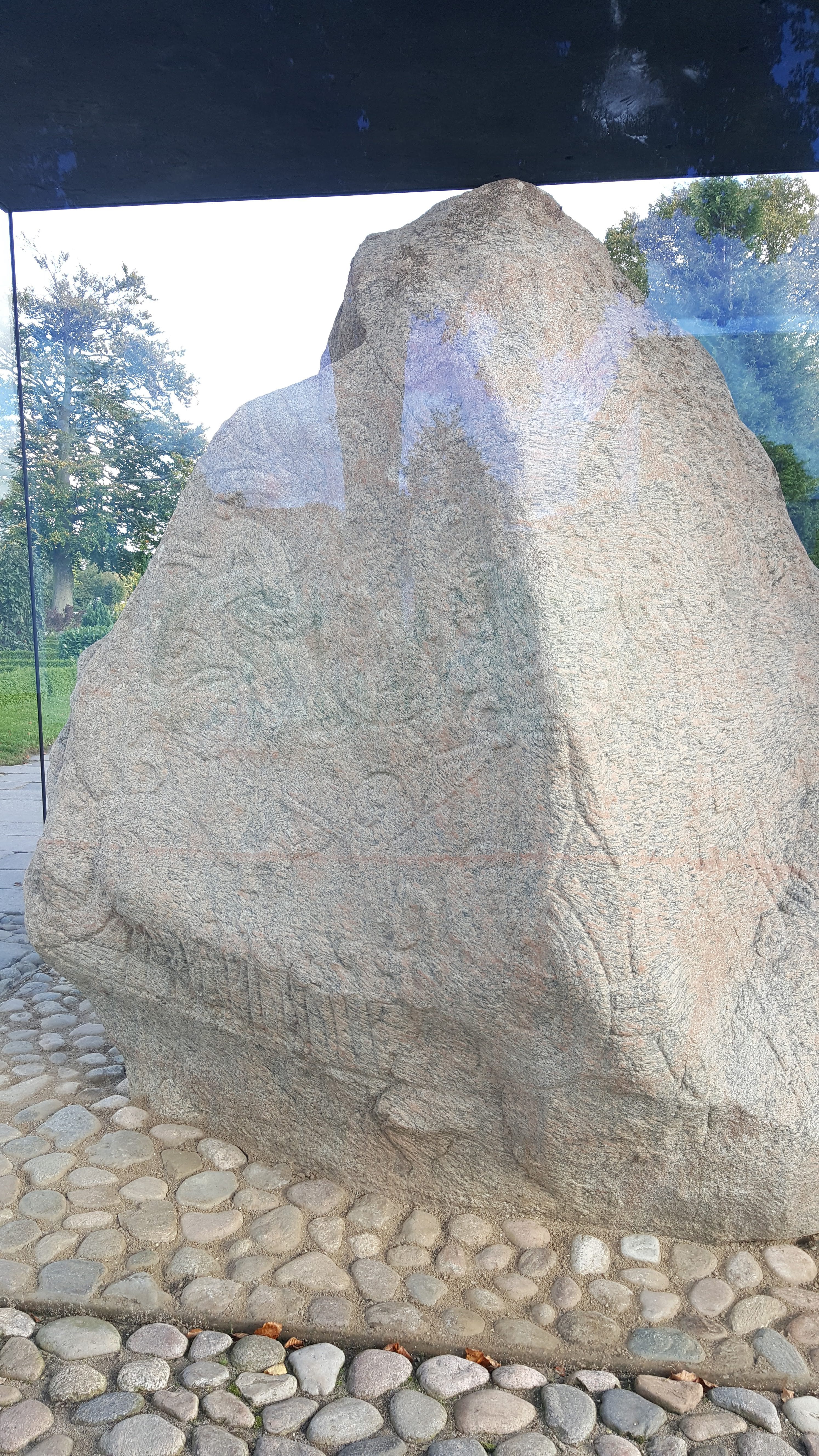

Harald Bluetooth’s rune stone, known as “Denmark’s Birth Certificate,” proclaimed Harald king of a Christian people

Harald Bluetooth built Jelling’s first Christian church near the sizable mound where his father was buried. Nineteenth-century archaeologists who dug into the mound were disappointed to find that Gorm’s burial chamber was empty, but later excavations revealed that Harald must have moved his father’s remains from the mound to the more sacred ground under the church, because they not only found bones there, but also a trove of royal artifacts. Today the site is marked by a twelfth-century church, as well as three large stones carved with pictures and runes commemorating Harald’s establishment of Christianity in Denmark. A newly opened, fascinating museum nearby helps visitors learn about the country’s early history and what daily life in a Viking fortress must have been like a thousand years ago.

Jelling Kirke sits beside the burial mound

A fresco inside Jelling Kirke depicting the Wise Men’s visit to baby Jesus

We left the Kongernes (Royal) Museum about 4:30 p.m. and got on a four-lane highway that would take us as quickly as possible to Ørslev Kloster, a former monastery where Nancy had arranged to meet the caretaker about 6:00 so that he could show us around the place before it got dark.

Our connection to Ørslev Kloster is similar to the one with Hopballe Mølle: the name appears on FamilySearch records as the place where several of Nancy’s great-grandmother’s forebears had been christened and buried. Unlike Hopballe, however, Ørslev Kloster was easy to find using Google Maps, and even in our Danish road atlas; it is located in the Nordfjends area about 16 km east of Skive. Figuring that kloster meant some kind of religious complex, Nancy googled the name and discovered that Ørslev Kloster had been a monastery. (Actually, it had been a convent, but for some reason the Danish word kloster always gets translated into English as monastery, so we’ll just have to live with that bit of inaccuracy.) Not only is the church still standing, but the former “monastery” is now operating as a retreat center. Photos at Ørslev Kloster’s website showed the place to be rustic and appropriately austere. How cool would it be, Nancy thought, to stay at a seven-hundred-year-old estate whose cemetery includes the graves of some of your ancestors?

The website indicated that guests seeking solitude in which to study or work could stay at the monastery anywhere from two nights to two months for about the same price as a cheap hotel room, so Nancy wrote to the proprietor. “I am an American whose great-grandparents emigrated to the U.S. from Denmark about 1860,” she said. “Several of my ancestors were christened and buried at Ørslev Kloster. My husband and I are not exactly seeking solitude, but rather a connection to my Danish heritage. Would it be possible for us to stay at the retreat center for a couple of nights in October?”

A reply came within a few days: “What a story! It would be an honour to welcome you and your husband back to your roots and give you a feel for the landscape, the history and the people.”

The caretaker, Garry Keyes, turned out to be an Irishman; Nancy is grateful that he is a native English-speaker because that made corresponding easier as they sent messages back and forth over the next several weeks. Garry had come to Denmark to study archaeology at Aarhus University (located in Denmark’s second-largest city, on the east coast of the Jutland peninsula). There he met the Danish archaeology student who became his wife, and twelve years ago they took over management of the retreat center at Ørslev Kloster.

Signs such as this one for Ørslev Kloster mark parish boundaries

Although Ørslev Kloster had been established as a Catholic convent around 1200, after the Reformation the estate was transferred to private hands. Over the centuries, a succession of owners remodeled the manor according to the styles of the times, but eventually it fell into disrepair. In the early 1930s, a countess named Olga Sponneck happened to ride her bicycle past the crumbling but still picturesque estate. Enamored, she bought the place and spent the rest of her life trying to restore it to its former manorial splendor. When she died in 1964, the countess left the property to a preservation trust, which then moved to turn the old monastery into a retreat center.

The church at Ørslev Kloster

It was just a few minutes after 6 pm when Michael and Nancy turned into Ørslev Kloster’s cobblestoned drive. Garry came out to greet us and then spent the next hour or so showing us around the main building, which exuded an understandably musty odor when he opened the first heavy door. We peeked into a couple of cells, each furnished only with a simple bed, a wooden chair, and a rustic table–although most of them also had a good modern lamp and a laptop set up on the table. (Garry explained: “Remind me to give you the wifi code. Wifi has become the modern manifestation of the Spirit–something none of us can live without!” The whitewashed halls were very quiet, but we did meet some of the other current residents: Jørgen, a writer who returns for a week or two every few months to recharge, and a young female intern who works in the manor garden.

An alcove in Ørslev Kloster

Garry pointed out the kitchen (residents are responsible for preparing their own meals), bathrooms, and sitting rooms that we were invited to use. “All the doors along the corridor look the same,” he said, “so to avoid accidentally walking into someone’s private room, check to see if there is a light switch next to the door. The common rooms are the only ones that have switches on the outside.” Near a door that opened onto the courtyard, Garry pointed to a rack full of rubber boots in various sizes. “There are a number of walking trails on the property that I encourage you to explore. Everything will be wet if not muddy, so feel free to borrow some wellies before you go out. And here’s a basket of wool socks if you need them.”

One of the old trunks found along Ørslev Kloster’s halls

Nancy noted several very large, very old trunks standing against the walls in the corridors. “I hope those don’t contain bodies,” she remarked.

Garry laughed. “Nothing so exciting, I’m afraid” he said, approaching one and raising the heavy lid. “We use these to store extra pillows and blankets. If you get cold, feel free to come and get whatever you need.”

This was the manor’s public reception room. Garry explained that all the estate’s tenant farmers–which likely included some of Nancy’s ancestors–would have come here at least once a year to pay their rent.

Another view of Ørslev Kloster’s reception room

After we had a chance to see the interior of the monastery church, Garry let us into the gardener’s former residence behind it, which will be our home for the next two nights. We had to shoo a few scruffy cats off the steps and out of the entry hall so we could carry our bags inside without tripping over them. We didn’t take time to get settled, however, because Garry reminded us that the local convenience store where we would need to pick up some juice and yogurt for tomorrow’s breakfast would close in fifteen minutes. “I need to get a few things myself, so you can follow me there,” he said.

Inside Ørslev Kloster Kirke

The door to our lodgings at Orslev Kloster–and its guardian

It was starting to get dark when we got back to the monastery; visiting the cemetery in front of the church would have to wait until tomorrow. We said goodbye to Garry, put our juice and yogurt into the refrigerator, and spent a few minutes exploring the house. The main floor includes a fairly large parlor, a bedroom, a somewhat modernized bathroom and kitchen, and a pantry; upstairs are two small bedrooms and a large, open room (maybe 15 x 30 feet) that looks as though it has been used variously for meetings, banquets, or extra sleeping space.

Our bedroom

Our parlor

Our kitchen

Although we weren’t terribly hungry after our bountiful lunch at Hopballe Mølle, we did want to eat something, so we drove about 20 minutes into Skive, the nearest town large enough to have a decent restaurant that was open tonight. We passed by a pizza parlor where a handful of teenagers were loitering and went next door to the Cafe Brogården, where we had the place entirely to ourselves the rest of the evening. The waitperson spoke some English but was unable to help us decipher many of the items on the menu, and the Google Danish-to-English app that Nancy had loaded onto her phone didn’t provide much better assistance: it translated grovfritter as “gross ferrets”–which certainly didn’t sound like something that should be on a dinner menu. (We finally determined that the word must be a local term for French fries.) What we ended up ordering (and sharing) was an Italian salad with prosciutto and pesto dressing, and a chicken sandwich on a crusty roll with Greek tzatziki sauce, which came with båd kartofler (“boat”-shaped roasted potato wedges).

Cafe Brogården (we arrived after dark; this photo was taken the next day)

Back at the monastery, we had to use the flashlight feature on our phones to help us navigate over wet cobblestones from the parking area to the front porch of the gardener’s house. When Nancy went upstairs to turn off a light we had left on earlier, she found a cat curled up in a soft chair and decided that she’d better scoop it up and put it outside lest it decide to join one of us in bed during the night. Meanwhile, Michael was downstairs searching for something to cover the windows, which gave everyone coming or going an unobstructed view into our bedroom. He was about to give up when he closed the bedroom door and noticed some canvas panels hanging on hooks behind it; their grommets fit exactly over protruding nails on either side of each window. Having thus secured a little privacy, we changed into pajamas, made up our beds with the clean pillowcases and duvet covers Garry had left for us, and drifted off to sleep.

Leave A Comment