Als Kloster on a sunnier day

Last night we had told the manager of the B&B that because we wanted to get to Hamburg by 10 a.m. to catch a train, we needed to leave Als Kloster by 7 a.m. Would we be able to get an early breakfast?

“I’m sorry, but we don’t start serving before 7:00,” she said, but she did give us the name and address of a bakery in town that opens at 6:30, suggesting that we could pick up something there to eat on our way.

It was as dark when we left Als Kloster this morning as it had been when we arrived last night, although the rain had let up a bit. We can’t tell you what the grounds looked like, but our room was so nice that we wished we could stay for a few more days. We couldn’t, however, so we loaded our bags into the car and were on our way by 6:45 a.m.

Only part of Lagkagehuset’s extensive offerings

Lagkagehuset, the bakery that the B&B manager recommended to us, is part of a chain, but other than that and the fact that it sells coffee, it bears no resemblance to Dunkin Donuts. The address we had been given took us to an area in the old center of Sønderborg with a lot of one-way and dead-end streets. We didn’t see Lagkagehuset on the first pass. We didn’t see it on the second pass. We did see it on the third pass, but we couldn’t find anywhere to park. The B&B manager had told us there was a parking lot at the rear that you could enter from a side street, but we couldn’t figure out how to get to the side street. After driving in circles for twenty minutes (and realizing that we probably could have finished a nice, hot breakfast already if we had just stayed and eaten at Als Kloster) we finally found a place to park, ran in and picked out a few buns and pastries from a vast array of tantalizing choices, paid for them and a couple of cups of varm chokolade, and hurried back to the car. Even when eating on the run, one cannot help but notice the superiority of Danish-made Danish pastries.

The place for salads at the Hamburg Hauptbahnhof

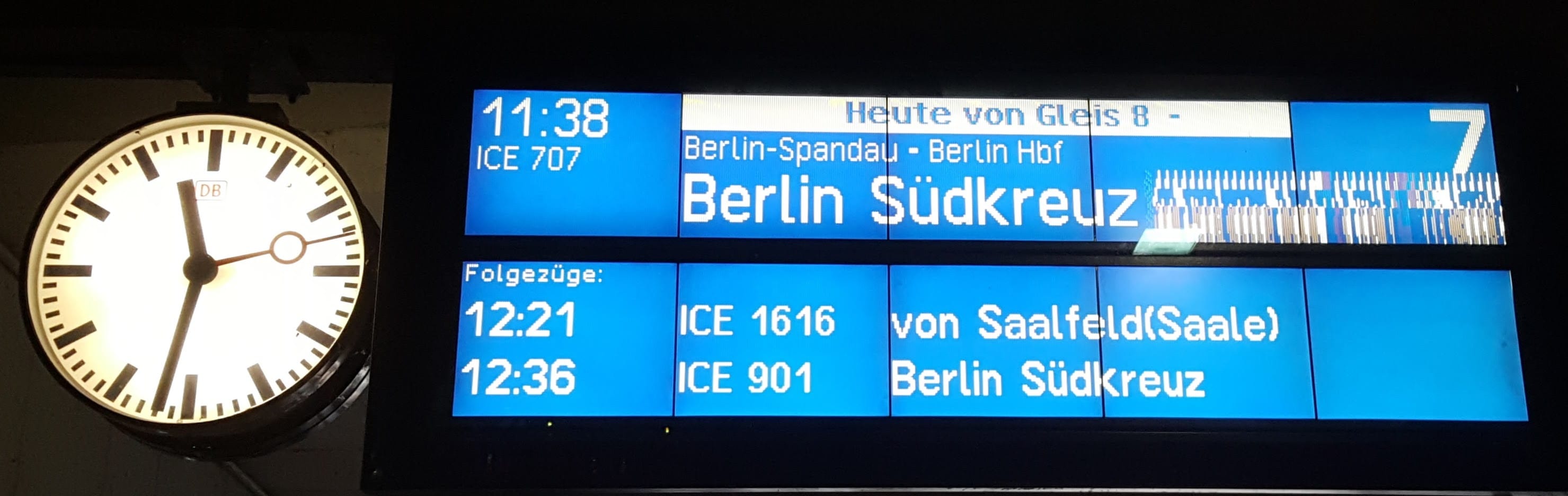

Fortunately, traffic heading into Hamburg this morning was not as heavy as it had been heading out of Hamburg on Sunday. Even the one-lane bridge over the canal did not cause much of a delay, and we realized after we had crossed back into Germany that there had been no border checkpoint at all to slow us down. We returned the rental car without any problem, and although we missed the earliest train we might have taken, we were in plenty of time for the next option. We bought a couple of salads-to-go from a kiosk at the Hauptbahnhof, paid €1 each to use the public restroom, then boarded the train for Berlin.

Pay toilets in the Hamburg Hauptbahnhof

(An observation about the public restroom: Although there are separate entrances for men and women, there is a connecting door in the wall between the two restrooms. When the attendant judged that the line on the women’s side was too long, she opened the connector and directed the next few women in line to use private stalls on the men’s side to prevent a backup. In Germany, practicality vanquishes prudery.)

Next train to Berlin

On the train, we had to jostle our luggage past many other travelers before we found two unoccupied seats anywhere near each other. As Nancy tried to push her backpack into an empty space on the overhead rack, Michael’s aluminum water bottle slipped out of the side pocket, clonking the middle-aged woman sitting underneath on the wrist. Nancy apologized with great sincerity as best she could using English and body language, but the woman still seemed aggrieved. Unfortunately, the empty seat that Nancy had planned to take–and the only one now available–was directly across a table from the injured woman. Realizing that they would have to face each other for the next couple of hours, Nancy tried to be particularly solicitous and the other woman gradually relaxed her hostile demeanor. Soon the two were chatting amiably. The other two passengers at the table were the injured woman’s husband, and a younger woman who spent most of the trip engrossed in her phone. (Michael had taken a seat farther down and across the aisle.) Nancy learned that the couple were from Hamburg, traveling to Berlin for a three-day holiday. She kept the conversation friendly by asking for recommendations of things to see and do during our visit. The couple had hoped to spend time strolling through the Tiergarten, but were rethinking that plan in light of the cold, wet, blustery weather forecast for the next few days.

U-Bahn station at Ernst-Reuter Platz, near Marty’s apartment

It was indeed cold, wet, and blustery when we deboarded the train about 2:00 p.m. Marty was waiting on the platform and greeted us with open arms and a big bunch of colorful flowers. Before we left the station, he helped us buy weekly transport passes that we promptly put to use on the bus and U-Bahn (underground) that would take us to his apartment, which is located near the Berlin Institute of Technology about midway between the Tiergarten and Schloss Charlottenburg (the baroque palace commissioned by the wife of Frederick the Great). It’s in a pleasant neighborhood where mid-rise residential buildings mingle with small shops, hotels, and theatres.

Looking down Marty’s street from the U-Bahn station

The street entrance to Marty’s apartment building

We pass–but don’t have to use–this elegant staircase to reach Marty’s flat

Marty’s apartment is on the ground floor at the end of this courtyard

We found the Wright place

Marty had made some “healthy cookies” (full of whole grains, honey, and raisins), which he served along with some hot rhubarb tea that was especially welcome after our wet, windy walk down the street from the U-Bahn station. We spent the rest of the afternoon reviewing the bullet points of our lives over the past thirty-five years and beginning to catch up on news that hadn’t been covered on our respective Facebook pages.

The story of how Martin Wright made his way from Murtaugh, Idaho (current population about 140, up from 124 in 1970), to Berlin, Germany, would make a good movie. Young Martin’s parents had recognized his natural musical abilities early and willingly drove him miles and miles each week so that he could take music lessons in communities that were less economically and culturally impoverished than Murtaugh. By the time he graduated from high school (one of only ten in his class), he had become a first-rate pianist and developed a lovely singing voice. On his first day of classes at Brigham Young University, Martin decided to sit in on the Opera Workshop to see whether he wanted to register for the course. When the piano accompanist failed to show up, Martin volunteered to fill in and so impressed the professor that he hired him for the rest of the semester. Martin had had little prior experience with opera but loved the workshop, and even though he spent most of the semester behind the piano, he absorbed a lot of lessons in dramatic vocal production and staging. In addition to the Opera Workshop and private voice instruction, Martin also participated in BYU’s Oratorio Choir that year–as did both Michael and Nancy. All three of us also lived in the same dorm complex, so our mutual friendship grew as we sang together, ate cafeteria food together, and walked back and forth to class together over the next several months.

Martin spent the next two years in Thailand, serving a mission for the LDS Church. At the time, most Mormon missionaries spent their time walking through residential neighborhoods knocking on doors, but Elder Wright’s experience was unusual. Recognizing that Martin’s musical abilities could open more doors than mere knocking, the mission president assigned Elder Wright and a few other talented missionaries to form a singing group, and arranged for them to perform on a popular television program. That appearance was such a success that the singing Mormons became a regular feature on Thai TV.

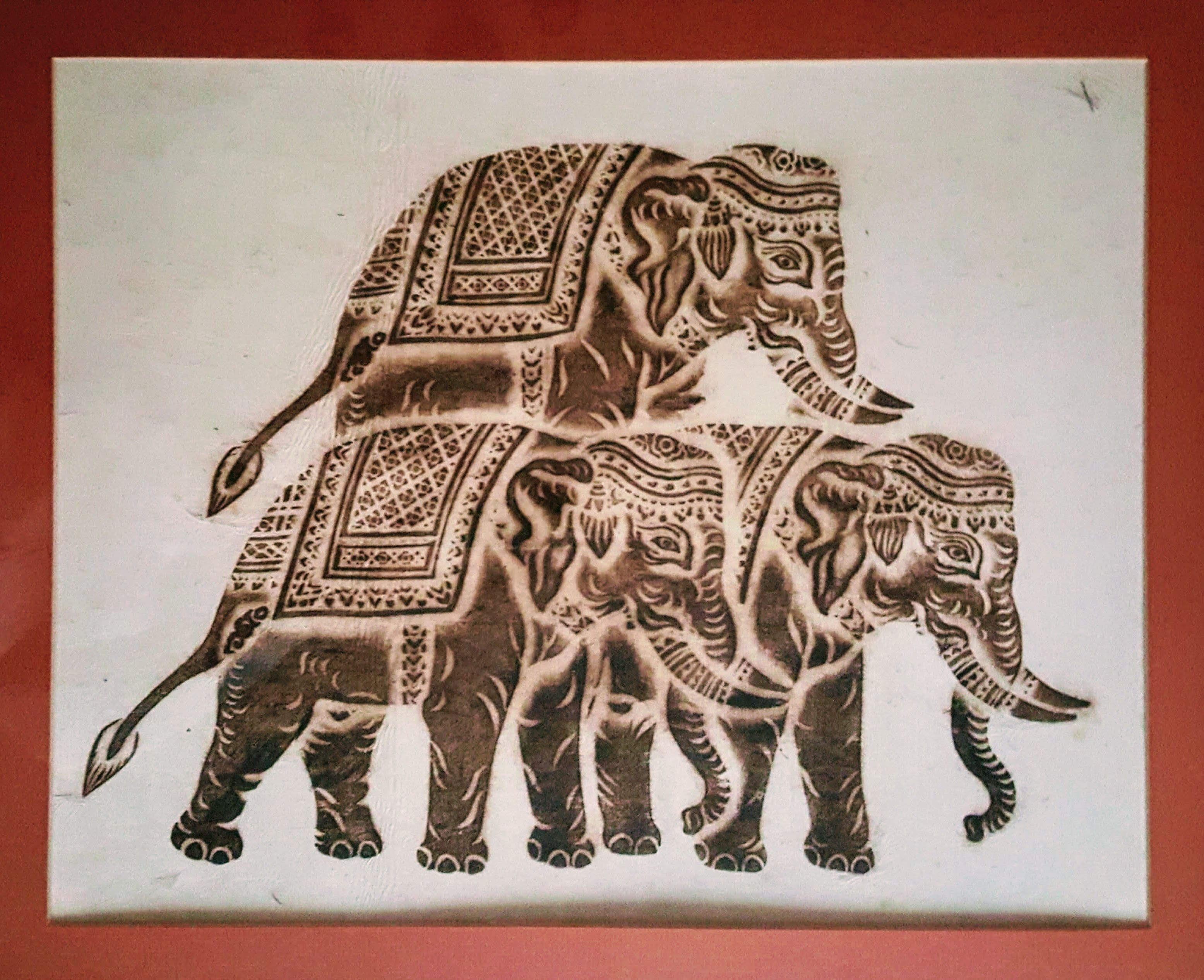

Marty made this brass rubbing while he was in Thailand on a mission. It’s been on display in our home for decades

A funny aside–or maybe this could be the opening scene of the movie: Not long ago, Marty went into a Berlin nail salon where most of the manicurists were from Thailand. While they clipped and filed his nails, he listened to them chatter with each other in Thai, but didn’t reveal that he could understand what they were saying until one of them told a joke that made him laugh. Stunned that this American customer had been following their entire conversation, they asked how he had learned Thai. When he explained that he had lived in Thailand for two years back in the 1970s, one of them gasped.

“Are you a singer? Were you on TV?” she asked. Marty replied yes on both counts.

“I knew you looked familiar!” she said. “I used to watch your program all the time when I was a teenager! You were great!”

Now it was Marty’s turn to be stunned.

Back at BYU after his mission, Martin decided to focus on vocal performance, but continued to develop a broad range of musical skills in his work with the opera program. After graduating from BYU and earning a Master of Music degree from the University of Arizona, he landed singing roles with several opera companies in the southwestern United States, while also gaining experience preparing opera choruses. A choral conducting assignment with the Los Angeles Opera gave Martin the opportunity to work with Plácido Domingo, one of the famed “Three Tenors” of the twentieth century. Domingo applauded Martin’s vocal performance but was even more impressed by his work with the chorus. He told him: “Martin, as a singer you have the ability to be one of maybe two hundred fine baritones competing for good roles–but as a chorus master, you have the ability to be one of the best four or five in the world.”

As Martin considered his future in light of this assessment, he realized that although he enjoyed performing, he was in it more for the music than for the fame. “I wanted to make the music shine,” he told us. “I didn’t care about being in the spotlight myself.” So he chose to concentrate on preparing outstanding choruses.

Since making that decision, Martin has served as chorus master of the San Diego Opera, music director of the San Diego Master Chorale, and principal guest conductor of the Lyric Opera of San Diego. In addition, for many years he was chief conductor of The Netherlands Radio Choir and chorus director of The Netherlands Opera. We were excited when Marty was named chorus master of the Lyric Opera of Chicago about five years ago, but a health crisis forced him to resign that position after less than four months on the job. Happily, a complete change in his diet and personal regimen restored his health, and in 2015, Martin was offered the position of chorus master at the Berlin Staatsoper (State Opera).

… which brings us back to the present. Marty left us alone in his apartment for a while this afternoon so we could rest, and so he could go to the bakery for a loaf of bread to eat with the Thai chicken soup he was preparing. Along with the bread, some homemade hummus, and carrot and celery sticks, the soup made a delightful dinner. Marty cleared the table and put away the leftovers while we changed into nicer clothes, and soon he was leading the way to the bus stop so we could get to tonight’s concert.

Most of the artworks in Marty’s furnished flat were painted by the owner. When he tried to take some down so he could hang his own choices, he discovered that they had been bolted to the walls

Shivering in the icy wind, we waited at the bus stop for probably fifteen minutes before Marty and several other Berliners decided that the bus must not be coming, so we hurried across the street and got on the U-bahn instead. The delay and the less-direct ride meant that we had to run a few blocks to the Berliner Philharmonie to avoid getting shut out of the auditorium for the first number. As it turned out, the concert’s start time had been delayed ten minutes to accommodate other audience members whose transportation had failed them–apparently, this afternoon’s windstorm had resulted in downed power lines and blocked streets all over town–so we had time to check our coats before finding our seats.

Normally, the 1960s-era, tent-shaped Berliner Philharmonie is home to the Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra. However, the ensemble on tonight’s program was the Staatskapelle Berlin, whose much older home at the Staatsoper unter den Linden has been under renovation for the past seven years. The Staatskapelle’s “conductor for life,” Daniel Barenboim, is also the musical director of the Staatsoper–and therefore Marty’s boss. Marty tells us that Barenboim likes his job because working for the state means he doesn’t have to do any fundraising.

In the lobby of the Berliner Philharmonie

After the first piece, an atonal, intentionally disorienting work by Berliner Jörg Widmann called Zweites Labyrinth (Second Labyrinth, composed in 2006), Marty turned to us and wryly remarked, “Well, that’s ten minutes of my life that I’ll never get back!”

The remainder of the program was more to our taste: Schumann’s piano concerto in A minor with pianist Maurizio Pollini, and Debussy’s Images pour Orchestre. Pollini’s hair has become considerably grayer and wispier than it was the last time we saw him onstage, probably with the Chicago Symphony around 1980, but tonight his hands didn’t betray his age. Pollini and Barenboim–whom we also had seen last in Chicago, back in the days when we could get student discounts–are both seventy-five. We’re glad that neither decided to retire before we had the chance to see them perform again.

Tonight’s dramatic view of the Kaiser Wilhelm Memorial Church (center) as we waited at the bus stop after the concert

Leave A Comment