Tuesday 11 July. We awoke to a beautiful day: a clear, blue sky with enough breeze to temper the bright sunshine. A beautiful day to be outside—but first, we had to eat breakfast. The chafing dishes at the Hôtel Kyriad’s buffet held strips of bacon and pre-cooked omelets that actually weren’t too bad; the apple juice was better than most, and the orange juice was freshly squeezed. The hot chocolate also was good. Only the baked goods were a little disappointing.

We left the hotel early enough to take the scenic route along the Seine River rather than the expressway to Giverny, home of the famed Impressionist painter Claude Monet (1840-1926), and still arrive just after the estate opened at 10 a.m. But already, the place was teeming with visitors. As travel guru Rick Steves explained:

“All kinds of people flock to Giverny. Gardeners admire the earth-moving landscaping and layout, botanists find interesting new plants, and art lovers can see paintings they’ve long admired come to life. Fans enjoy wandering around the house where Monet spent half his life and seeing the boat he puttered around in, as well as the henhouse where his family got the eggs for their morning omelets” (Rick Steves’ Paris 2016).

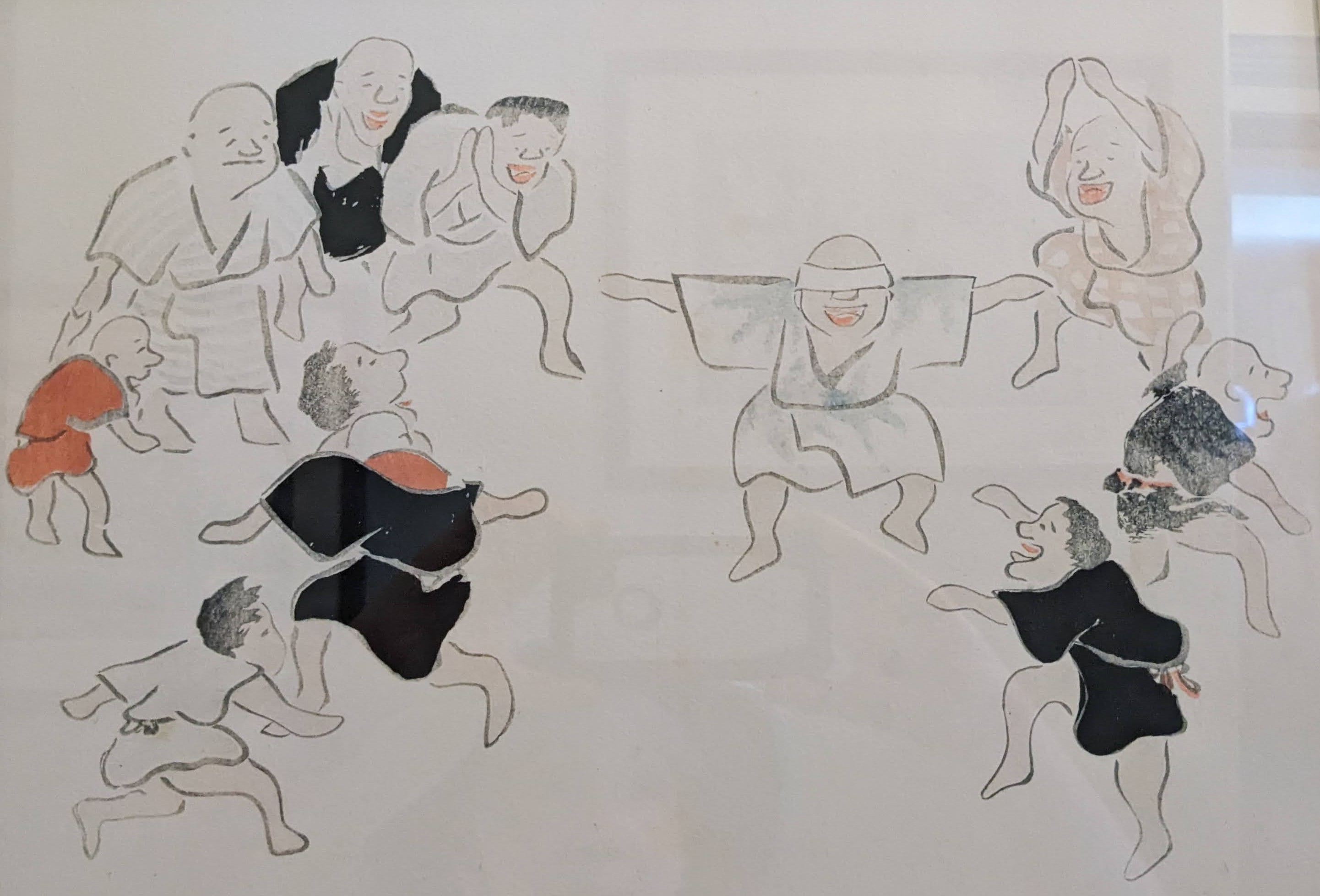

We joined scores of other visitors for a self-guided tour of the house, in which nearly every inch of available wall space is occupied by artwork: not only paintings by Monet himself, but also by the many friends who came to paint at Giverny, including Paul Cézanne, Auguste Renoir, Camille Pissarro, and Berthe Morisot. Monet also amassed a collection of more than two hundred prints by Japanese artists. (Most of the artworks now on display at Giverny are copies; the originals are in more secure museums elsewhere.) Besides all the prints and paintings, what stands out most about the house is the vibrant color everywhere: sky blue, sunshine yellow, and warm terracotta. It’s a big house, expanded over the years to accommodate Monet’s large family and their guests. He and his first wife had two sons, and his second wife, with whom he was living when they moved to Giverny in 1883, had six children of her own. One of them, Blanche, married Claude’s son Jean, and returned to Giverny to take care of her aging stepfather/father-in-law and his estate in 1914, after both her mother and her husband died. A painter herself, Blanche stayed at Giverny until her own death in 1947.

Monet’s House at Giverny

Monet’s house at Giverny |

Monet’s study |

Monet’s bedroom with homage to Cézanne |

Monet’s atelier (workshop) |

Blanche’s bedroom |

A humorous sample from Monet’s Japanese print collection |

Dining room |

The artist in his dining room. Not much has changed since his time |

Blue and white tiles in the kitchen form a nice background for the copper cookware |

More color blooms outside in the gardens, which Monet designed himself. A staff of gardeners helped him clear the property of pine trees and establish a formal pattern of symmetrical flowerbeds with a wide alley down the middle, shaded by trellises of climbing roses. The formality ends with the layout, however; the beds are filled with a jumble of blooming plants that offer riotous color all year long. On this day in mid-July, hues of red, orange, yellow, and fuschia predominated. Pat was particularly enchanted by the mimosa trees, a species she didn’t remember seeing before.

“Would these grow in Utah?” she asked.

“I don’t know about Utah, but they grow in Cincinnati,” Nancy told her. “We have some in our neighborhood.” (Later, while visiting Salt Lake City, Nancy noticed a mimosa growing around the corner from our daughter Hillary’s house and snapped a photo to send to Pat. Yes, they do grow in Utah.)

Walled Garden at Giverny

Looking at the walled garden from the house |

Inside the walled garden |

Nancy, Michael, and Pat under the trellises |

Gladiolus |

Mimosa tree |

Black-eyed Susan |

Tiger pavonia |

Phlox paniculata |

Lucifer crocosmia |

Across the road from the house and symmetrical garden is the water garden, where Monet created a large pond by diverting water from the nearby Epte River, a tributary of the Seine. The pond is surrounded by big trees that offer shade to a variety of flowering plants, and is home to the water lilies that became the subject of many of Monet’s most famous paintings. It’s a lovely, restful place to wander—even when you have to share the space with a lot of other tourists.

Water Garden at Giverny

Lily pond |

Gardeners regularly clean out the pond |

The brook Ru feeds the pond |

Viburnum opulus |

Ball dahlia |

Orange day lily |

The town of Giverny comprises many half-timbered houses with walled gardens such as this one. Some have been converted to B&Bs

Monet’s estate is only the centerpiece of a small, picturesque town filled with charming little hotels, boutiques, and cafés. We were attracted to Au Temps des Fleurs first by the covered patio at the front of the restaurant, and then by the beautiful plates of food we saw being presented to people already seated there. We managed to get a table before the noon rush began and enjoyed a marvelous meal of imaginatively composed salads and luscious desserts.

Lunch at Au Temps des Fleurs

The dining pavilion at Au Temps des Fleurs in Giverny |

Michael and Pat wait for lunch to be served |

Mille feuilles (a thousand leaves) of sliced tomato, fresh mozzarella, and avocado, garnished with chopped chives, slivered almonds, and balsamic vinaigrette |

The salade du jour: cantaloupe, watermelon, and feta cheese over greens, topped with thinly sliced chorizo and orange balsamic vinaigrette |

Raspberry and mango pavlova |

Puff pastry with raspberries and whipped cream |

We didn’t get to visit the house in Auvers-Sur-Oise where Vincent van Gogh ended his life, but his painting of another house in the village, painted just a few weeks before his death in 1890, is on view at the Toledo Museum of Art in Ohio

After an unforgettable morning in Giverny, we had planned to spend the afternoon in Auvers-sur-Oise, the town where another famous artist, Vincent van Gogh, had spent the last months of his life. However, when Michael rechecked the website for the house in which van Gogh had lived and worked—now a museum—he was disappointed to learn that the site was currently closed. So with a now-unscheduled afternoon on our hands, we decided to go back a few kilometers to the town of Vernon, which had caught our attention as we passed through on the way to Giverny.

Les Tourelles (The Turrets) overlooking the Seine at Vernon

Le Vieux Moulin (The Old Mill) in Vernon

Situated on the banks of the Seine River, Vernon was established in the twelfth century at the border between the sovereign lands of France and territory controlled by the dukes of Normandy. We enjoyed exploring the grounds of Les Tourelles (The Turrets], a small castle overlooking the river, but were disappointed to find that it had nothing but dust and cobwebs inside. The nearby medieval-era mill standing on the remains of a stone bridge over the Seine looked intriguing, but we agreed it was best to heed the signs warning visitors not to enter the derelict building. Today, Vernon appears to have become either a bedroom community or a weekend getaway for people from Paris, easily accessible from the capital in about an hour by rail or an hour and a half via the expressway.

Paris was our ultimate destination for the day, but we still had a few hours before we needed to get there. On a whim, we decided to head toward Beauvais in hopes of seeing Sinclair, Phillip and Patricia’s son, who had started a new job there at the beginning of the month. We called to see if he might be able to meet us, but because he was so new on the job, and because our request was so unexpected, he did not feel that he could ask for any time off that afternoon. But we were glad to hear that he’s very happy with his new position.

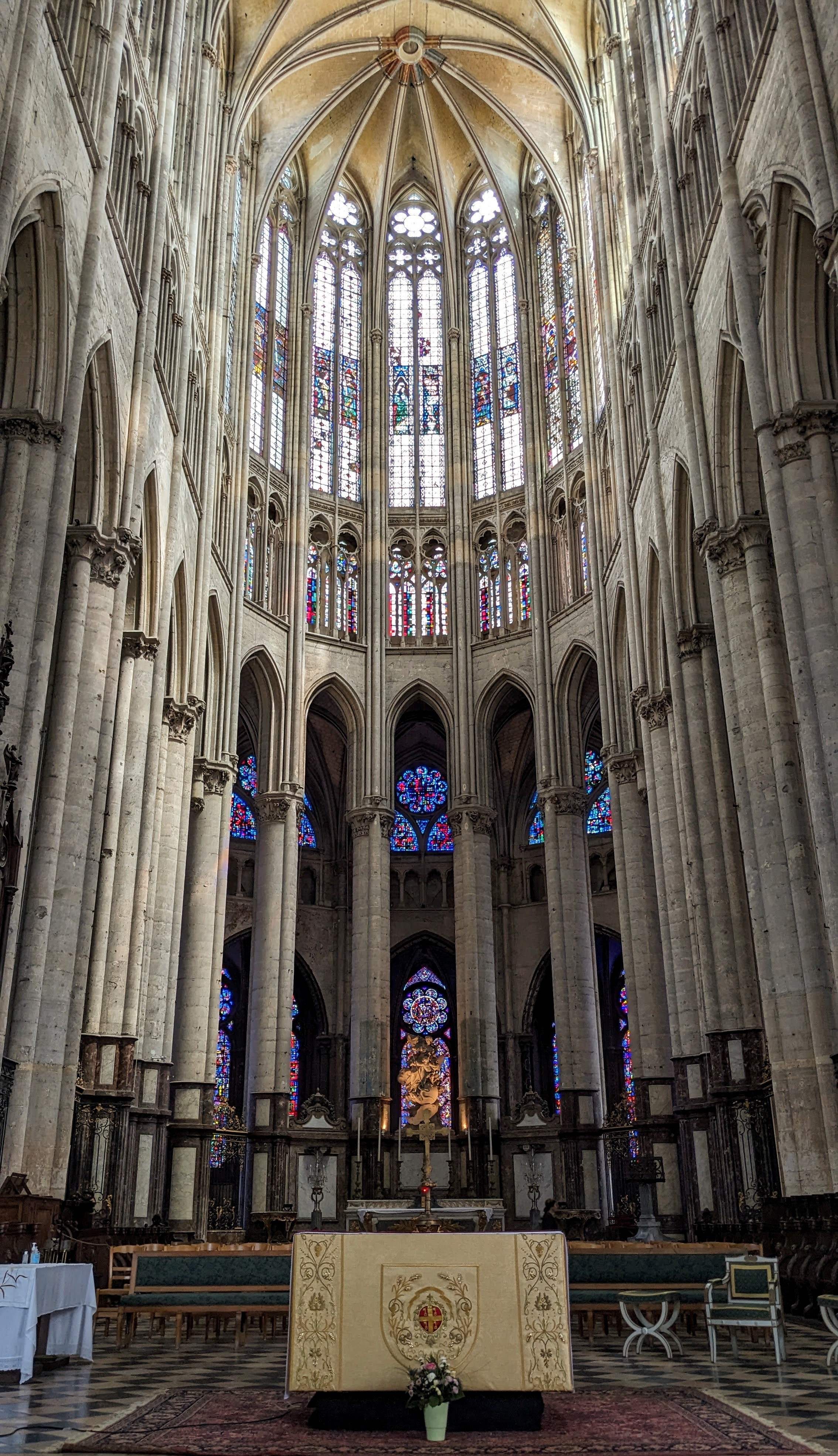

We went to Beauvais, anyway, because we knew the cathedral would be worth a visit. At more than 48 meters (159 feet) in height, the Cathédrale Saint-Pierre de Beauvais was once the tallest building in the world. Back in the thirteenth century, construction engineers in the town of Beauvais were in competition with construction engineers in the town of Amiens (about 65 kilometers/40 miles to the north) to see who could build the largest cathedral. Both projects involved erecting gothic-style arches that would let in plenty of light, and vaulted ceilings that could reach the heavens. Such heavy stone work required adequate back-up support from flying buttresses. Amien eventually won the competition; its cathedral is the largest in France (more than double the size of Notre-Dame de Paris), but Beauvais prevailed in terms of height, and still has the highest vault of any church in Europe (four feet taller than the dome of Saint Peter’s in Rome). Looking up at the ceiling of the choir is wow-worthy. But although the builders achieved such impressive heights, their aims had literally been too lofty. In 1284, only twelve years after the choir was completed, part of the vault collapsed, taking a few flying buttresses with it. The damage was repaired and construction resumed, continuing on and off over the next few centuries, but enthusiasm waned as architectural trends changed and funding became less consistent, so the Beauvais Cathedral was never completed as originally designed. The traditional floor plan for a cathedral forms a cross: the choir is the top, the transepts are the cross pieces, and the nave is the base. Beauvais has no nave; the tenth-century church of Notre Dame de la Basse Oeuvre (Our Lady of Menial Work—what an evocative name!) still stands where the nave of the cathedral was supposed to be built. However, the choir and transepts were finished enough for the church to be used as intended, and the cathedral remains a beautiful, though truncated, example of gothic architecture.

Beauvais Cathedral

Cathédrale Saint-Pierre de Beauvais |

The windows in the Our Lady Apse have survived since the 13th century. They include depictions of Christ as a child and his lineage from Jesse to Joseph |

Detail of south portal, Beauvais Cathedral |

Choir vault, Beauvais Cathedral |

Additional interior buttresses detract from the aesthetics, but are necessary to keep the vault from collapsing again |

The astronomical clock, added in the 19th century to fill an unattractive gap in an unfinished wall, features the Twelve Apostles surrounding Christ. The cathedral staff sells tickets to watch the clock go through its motions every hour |

Notre Dame de la Basse Oeuvre, the 10th-century church that was supposed to be razed so the cathedral’s nave could be built on the site |

Connecting annex between Beauvais Cathedral and Notre Dame de la Basse Oeuvre |

Across the street from the cathedral, 10th-century towers guard the gate to the former home of the bishop of Beauvais. The residence is now a museum |

Just as the builders of Beauvais Cathedral had to deal with a discouraging setback nine hundred years ago, we had to deal with some unexpected setbacks of our own as we headed back toward Paris. Getting through the rest of the afternoon and evening felt like running an obstacle course.

Obstacles Along Our Path

Holiday Inn Express Roissy

Obstacle 1: From Beauvais, we planned to go straight to our lodging for the evening, the Holiday Inn Roissy, located next to Charles de Gaulle Airport. There we would check in and leave our luggage before driving into the center of Roissy-de-France for dinner.

Finding the airport was not a problem, and finding the Holiday Inn was not a problem, but finding the right road to reach the actual entrance to the Holiday Inn was a problem. Round and round the airport we went, three or four times, but persistence and keen attention to lane dividers finally paid off. However, once we had deposited the luggage in our rooms and returned to the car to go to dinner, we found that we were trapped in the hotel’s parking garage because the ticket the desk clerk had given us would not open the gate. Fortunately, a nice British couple drove up behind us a few minutes later and opened it for us with their ticket.

Aux Trois Gourmands had a shady patio

We passed the Fontaine Saint-Jacques de Compostelle on our walk from the carpark to the restaurant in Roissy. Locals say this was a watering place for medieval pilgrims from the north on their way to Santiago de Compostella in Spain, but can’t prove their claim

Obstacle 2: Finding Aux Trois Gourmands, our restaurant in Roissy, was easy, but finding a place to park was next to impossible. Nothing was available on any street in the vicinity. We saw a carpark that looked like it had a few vacant spaces, but once we entered, we noticed a sign indicating that all spaces were reserved for employees of the adjacent business, so we found the exit and kept roaming the streets. Finally, Michael consulted Google Maps and located a public carpark a few more streets away. We were relieved to find several open spaces there, but we now had a twenty-minute walk back to the restaurant.

The restaurant’s elusive QR Code

Obstacle 3: It was a pleasant evening, so we seated ourselves at an open table on the trellis-enclosed patio in front of Aux Trois Gourmands. When we asked for menus, however, the server told us there weren’t any. Instead, he gave us a card with a QR code by which we were supposed to access the carte du jour, but because the data provider for Michael’s phone was UK-based instead of French, the QR code would not work (Neither Pat nor Nancy had data access, either.) The server did not seem concerned about this, and left to take orders from diners at other tables. We noticed that most patrons who had arrived ahead of us were eating galettes, but none of us was keen on eating galettes for the third time this week. A sign attached to a trellis seemed to indicate that the restaurant was well-known for its churrasco-style grilled meats (which sounded great) but we had no way of knowing exactly what dishes were available. After trying in vain for about ten minutes to get the QR code to work, Michael went inside to seek help from the manager, who lent us his phone so we could look at the menu. The three of us bumped heads trying to get close enough to read the tiny text, but within a few minutes we had decided that Pat and Nancy would share half a grilled chicken, while Michael had a platter of grilled pork ribs. Our meal also included roasted potatoes and salad. The food was simple but good, and dining al fresco was nice even though patrons at other tables felt free to light up their cigarettes; fortunately the breeze carried most of the smoke away from us. It wasn’t until we were leaving that we noticed, posted on a wall near the front door, a large menu listing everything the restaurant had to offer. We had not seen it earlier because we had never gone through that door.

Michael at the gas pump. The price, converted from liters to gallons and euros to dollars, worked out to over $7 per gallon

Obstacle 4: With our stomachs now full, it was time to fill up the Citroën’s fuel tank before returning the car to the rental agency. Google Maps directed us to the closest gas station not within the boundaries of the airport, which turned out to be a set of pumps in an industrial park that were for the exclusive use of large commercial trucks. The next closest gas station was 15 minutes away, and the difference in price between what we paid there and what we would have paid at the airport was negligible. (Next time we need to return a rental car in an unfamiliar area, we’ll just go to the gas station at the airport.)

CDG rental car return lot

Obstacle 5: With the Citroën’s tank refilled, we clicked on the address of the National rental car agency at CDG provided by Google Maps and followed the directions on the GPS screen. We were near the airport when the screen indicated, “You have arrived,” but there was no National agency to be found. There were no rental car agencies of any type in the vicinity, only big, nameless corporate office buildings. So we began following signs for the airport terminals, hoping that we’d eventually see signs for the car rental return. We never did. After three complete, fruitless circumnavigations of the airport, Michael remembered that when we had picked up Pat at Terminal 2C the previous week, he had noticed a rental car lot across from the passenger pickup point. So on our fourth circumnavigation of the airport, we followed the signs for Terminal 2C and, voilá, there was the rental car lot! The airport had provided literally no signage to help renters find the right place to return their vehicles.

“Y a-t-il quelqu’un en charge ici?” (“Is anyone in charge here?”)

Obstacle 6: We found the National rental agency, but no one was on duty in the booth to process our return. We had no Help number to call, so all we could do was hope that someone would show up behind the counter before too long. As we waited, we determined that the first address Google Maps had led us to must have been the site of National’s local administrative office—not very helpful when it’s 9 p.m. and you just want to return a car. Eventually, a man came into the booth, apologized for keeping us waiting, and completed the necessary paperwork as efficiently and sympathetically as he could.

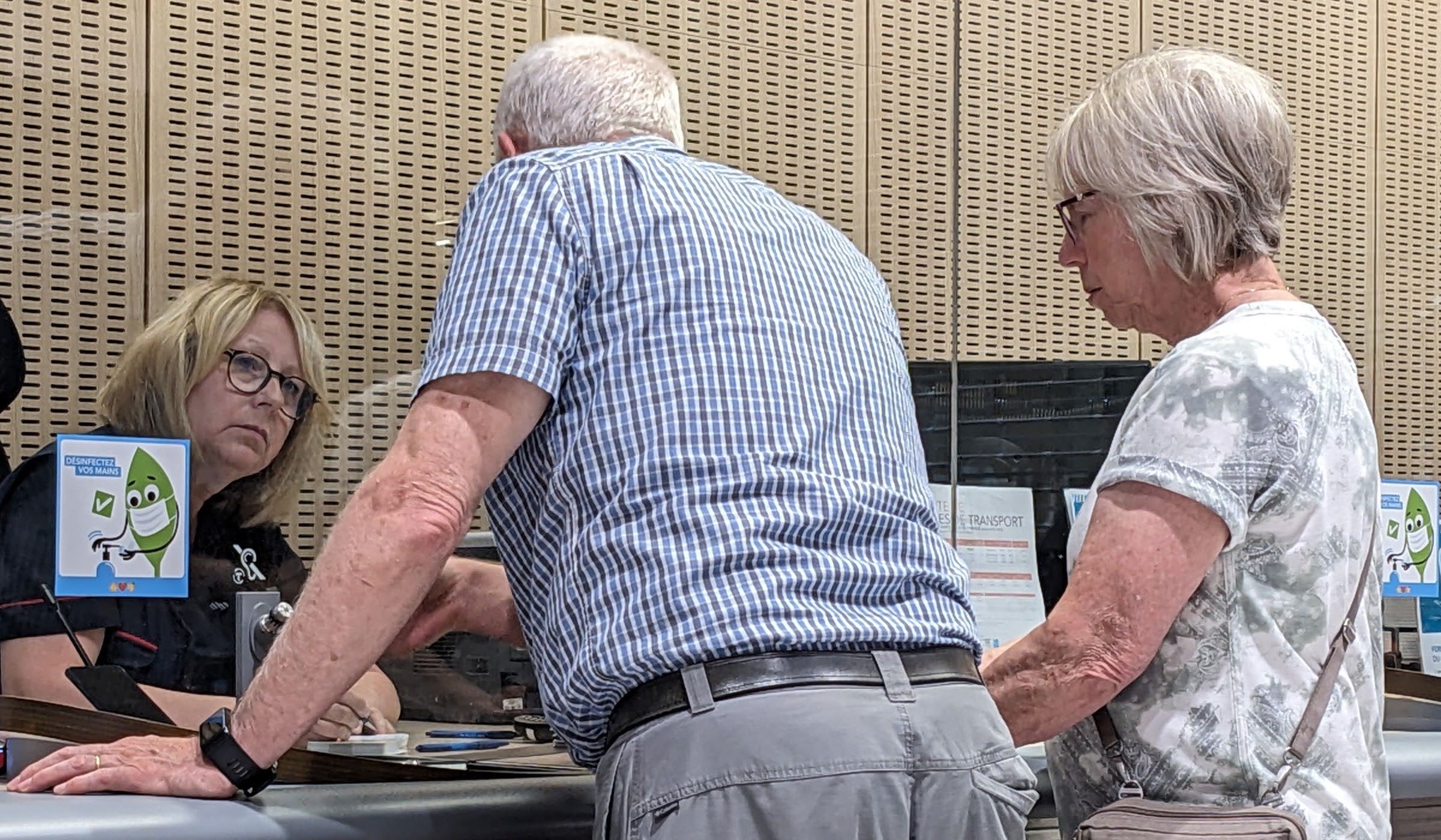

Trying to procure Navigo cards at the SNCF service counter

Obstacle 7: Our next task before we could take the airport tram back to the Holiday Inn and get into bed was to purchase Navigo cards, multi-use passes for public transportation within the Paris metro area, which we would need first thing in the morning. Michael asked the car rental agent where we needed to go to buy them, and he kindly explained exactly where to find the service counter for SNCF (Société Nationale des Chemins de fer Française, France’s national rail transport system) within the air terminal.

We found the SNCF counter easily, but there was a long queue, and only one clerk was working. It was now past 9:30 p.m. and we ended up waiting more than half an hour before reaching the front of the line. Pat would need only a one-day, all-zones pass for the travels around Paris we had planned for the next day, so she was able to make her purchase without any trouble. However, Michael and Nancy would be staying in Paris for a few additional days after Pat went back to the U.S., so each of us needed a longer-term Navigo card with our photo on it. Corinne, the English-speaking, incredibly patient SNCF clerk, told us where we could find a Photomaton downstairs. As we walked toward it, we saw a young couple come out of the booth and pull their photos from the machine, but when we tried to do the same, we could not get the machine to print our pictures. As we headed back upstairs to ask Corinne if she could suggest an alternative, we noticed another Photomaton around the corner from the SNCF counter. Why had the clerk sent us downstairs instead of to this one, which was much closer? Maybe she already knew what we soon discovered: the touchscreen on this Photomaton was stuck on a message that said (in English), “Printing in progress. Please remove your card.” Tired and frustrated, we returned to the SNCF counter, queued up again, and then explained our predicament to Corinne.

She sighed. “Do you have your passports with you?” We did. “I’m not really supposed to do this,” she said, “but if you’ll give them to me, I’ll take them in the back and make photocopies of your pictures.” We were so grateful she was willing to take pity on a couple of weary Americans—and grateful that Pat was willing to lean against a wall for nearly an hour without complaint while she waited for us to finish our business.

It was about 11 p.m. by the time we got our Navigo cards, and we still had to take the tram from the airport to the hotel. Although we had to leave again by 8 a.m. the next morning, at least we didn’t have to be ready to check out; we would spend another night at the Holiday Inn after a full day of activities in Paris on Wednesday.

Leave A Comment