One morning during our daily devotional and staff coordination meeting, a question arose about whether some Church branches around the country contributed money instead of commodities to support the Labour Missionaries who were building the Church of College of New Zealand and the temple here in Hamilton during the 1950s. Virginia K, a local Church member who volunteers as a receptionist and research aide in our reading room, had grown up in Kawhia, the small seaside community we had visited a few days earlier, and she remembered what the Latter-day Saints in her branch had done to support the building effort when she was a child.

One morning during our daily devotional and staff coordination meeting, a question arose about whether some Church branches around the country contributed money instead of commodities to support the Labour Missionaries who were building the Church of College of New Zealand and the temple here in Hamilton during the 1950s. Virginia K, a local Church member who volunteers as a receptionist and research aide in our reading room, had grown up in Kawhia, the small seaside community we had visited a few days earlier, and she remembered what the Latter-day Saints in her branch had done to support the building effort when she was a child.

“No one in Kawhia had any money, so we gave whatever food we could,” Virginia said. “Most of the time we sent fish, but sometimes we didn’t even have fish, so our parents would take us out to dig for pipis. I remember going out to dig for pipis many times. We’d fill up big sacks with them, and load them onto a truck to send up to the boys at The Project.”

“That’s right,” said Vic, another local volunteer who, with his wife Rangi, had recorded scores of interviews with former Labour Missionaries. “Sometimes that’s all there was to eat at the [construction] camp: pipi soup.”

Those of us who did not grow up in New Zealand exchanged puzzled glances. “What are pipis?” one of us finally asked.

What the locals call “pipis” are known as cockles or littleneck clams in other parts of the world

“They’re a kind of shellfish,” said Virginia, “something like a clam, but with a rounder shell. They live in the sand in some places along the shore. You can go out at low tide and dig them up. There used to be a lot of them in Kawhia, but I don’t know how many are out there anymore. It’s been years since I went digging for pipis.”

“What do they taste like?” Michael asked. “Are they good?”

“They taste like clams,” said Vic. “And yes, they’re very good.”

“Well,” said Barry. “It sounds like we need to organize an excursion to Kawhia to dig for pipis one of these Mondays.” He may have been joking, but some of us thought it was a fine idea—a unique cultural experience not to be missed.

The subject of pipis was dropped and mostly forgotten, however, until about ten days later, when Virginia made an announcement during our staff meeting.

“It’s all set,” she said. “I asked our branch president in Kawhia to check the tide schedule, and he said that low tide will be at 9:30 a.m. this coming Monday. The following Monday it’s at 6:30 a.m. and I didn’t think you all would want to get up at 4:30 to get there in time, so this Monday looks like the best day to go. You’ll need to leave here about 8:00. Koro and I can meet you at the highway turnoff at 9:15 and show you where to go from there. Then when we’ve collected the pipis, you can come over to our place, and we’ll eat them for lunch.” (Koro is Virginia’s husband. They split their time between homes, usually spending the workweek in Temple View and weekends in Kawhia.)

“We’re going to Kawhia to dig pipis?” we asked, excited. “We’re really going to dig pipis?”

More questions ensued. What should we wear? Do we need to bring shovels? How hard is it to find the pipis? How do you know where to dig? Should we bring buckets or something to collect them in?

Virginia and Vic recommended that we wear old clothes because we were likely to get very muddy, and with the fine, black sand of Kawhia’s beaches, the mud was likely to stain. And you’ll want to wear shoes, they said, because otherwise your feet might get cut walking over piles of rocks and shells, but wear old ones that you don’t care about because they’ll get really muddy. Shovels? Optional; most people just dig with their hands.

“What can we bring to contribute to the meal, Virginia?” asked Eva.

“Yes, what can we bring?” asked the rest of us.

Virginia thought for a moment. “Well, if you don’t think you’ll like the pipis, then you can bring whatever you like to eat. As for me, I’m just going to eat pipis!”

Going to Kawhia for pipis occupied much of our conversation over the next few days. The American women made plans to bring side dishes to go with the pipis, because even those of us who figured that if we liked clams, we’d like pipis, still wanted something more to eat than mollusks. And, having determined that most of us missionaries had not brought any old shoes suitable for such an expedition, we decided that we all needed to make a trip to the Op Shop.

Hamilton Hospice “Opportunity” Shop

“Opportunity Shop” is the Kiwi term for a thrift store, commonly shortened to “Op Shop.” These second-hand stores are ubiquitous in New Zealand, and—at least among the people we associate with—shopping at the Op apparently does not provoke the same sniffs of disdain that shopping at Goodwill or the Salvation Army does in the U.S. Here, it seems, no one is above wearing a second-hand suit, and everyone is proud to show off the bargains they found at the Op.

So on Thursday, the one day each week when Hamilton’s biggest and best Op Shop is open, we missionaries took turns leaving our duties at the History Centre to go hunting for old shoes. Michael and Nancy had been to the Op once before (hoping to find another nightstand) so we knew what we were getting into, which perhaps is why Michael viewed the prospect of buying shoes there with some distaste. Nevertheless, he pulled a few pairs from the shelves and began trying them on. Nancy found a pair of beat-up sneakers that fit, and Michael finally settled on some worn but snazzy gray imitation leather brogues.

Because all seven of us full-time senior missionaries were planning to go on the excursion, Michael arranged to borrow one of the mission vans again so that we could ride together. On Monday, we met in the parking lot next to the MCPCHC at 8 a.m. and piled all our gear into the back of the van: buckets, towels, extra shoes and clothing, plastic garbage bags, and food—side dishes to supplement the pipis. Michael, feeling confident after having navigated the winding road to Kawhia only two weeks earlier, offered to drive. He was glad that even though it was a weekday morning, traffic was light because more people were heading into Hamilton than out of it.

Koro and Virginia

Davis (right) begins to organize the group while Barry, Nancy, and Alan unload the van and change shoes

Virginia and Koro were waiting to meet us at the crossroad at the appointed time, as were Vic and Rangi, who had come in their own car. Peti, one of our museum guides, had come along with them to keep Rangi company while the rest of us went out across the sand to dig. (Rangi had only recently come home from the hospital after major surgery. She wasn’t ready to dig for pipis, but didn’t want to be completely left out.) Another couple from Temple View, Bill and Rebecca, had overheard Virginia talking about plans for the trip earlier in the week and invited themselves to join the party. So, including Davis, the Kawhia Branch president who was to be our guide, we were a party of fifteen—senior citizens all. If anyone else had been out on Aotea Harbour (over the hill behind the town of Kawhia) that morning, they would have been amused at the sight of us.

Rangi stayed bundled up in Davis’s buggy

Davis had arrived in a four-wheeler “buggy” and invited Rangi and Peti to ride with him to the shore so they could get a little closer to the action. Once the buggy was safely situated at the edge of the sand, Davis struck out across the mudflats, beckoning the rest of us to follow on an unmarked path stretching for miles and miles toward the sea. We hadn’t gone far before we realized that Davis intended to take us way out there, because he soon got so far ahead of us that he looked about the same size as the seagulls.

Starting across the mudflats

You know those cartoons where Elmer Fudd or Porky Pig (or maybe Homer Simpson, if you’re from a later generation) fails to notice the sign that says “DANGER! QUICKSAND” and steps right into the muck, gradually sinking up to his neck until help arrives just in the nick of time? Well, we may not have sunk up to our necks, but now we know that quicksand is for real.

Slogging through the flats

Attempting to pick our way over what we hoped was the driest path while trying to keep an eye on Davis’s ever-diminishing figure meant that the dozen of us behind him got widely separated from each other, so when we got stuck up to our knees, we were pretty much on our own to pull ourselves out. Fortunately, none of us lost our footing completely and fell headlong into the mud, although Eva came pretty close; she was immobilized, leaning on an elbow for several minutes until Michael and Alan could go back and extricate her. Not until later did we learn that instead of avoiding the rivulets of water streaming back out to sea, we should have been walking in them, because water tends to follow surface trails where the sand is most firmly packed.

Wendy and Diane were smart: they held onto each other to avoid falling

Once we caught up with Davis, it was kind of alarming to turn around and see how far away the shore was, realizing how far we would have to go to get back to safety when the tide turned. But because we had not “come that far only to come that far,” we bent over and started digging for pipis.

Earlier in the week, Nancy had done some research and discovered that what local Kiwis call pipis are actually littleneck clams, the New Zealand variety of a mollusk called cockles in the British Isles. (The Maori call them tuaki or tuangi; we don’t know where the name pipi originated.) These bivalves have a rounded, ridged shell, which they can open to feed on plankton or to extend a “foot” to help them burrow into the sand. Learning that these creatures are basically clams made us much less apprehensive about having to eat them.

Rebecca, Eva, Wendy and Barry trying to clean up

Michael removing his op-shop shoes, ready to trash them

Unfortunately, though it was a perfect day to be working on the beach—overcast but not drizzly, neither too hot nor too cold—it was not a great day for collecting pipis. Davis explained that the bays around Kawhia had been so over-harvested in recent years that the cockles had not had a chance to recover, so although we easily found a lot of them by digging our fingers four to eight inches into the sand, most were no bigger than an apricot pit. A mature cockle should be about the size of a whole apricot, and we didn’t uncover many of those. Nevertheless, we managed to fill our buckets with petite pipis before Davis indicated that it was time to head back to shore about 11:00.

Aoteo Nature Reserve, looking toward the Tasman Sea

After cleaning up the best we could, we got back in the van and followed Virginia and Koro to the Aoteo Nature Reserve, near where Virginia’s Maori ancestors had settled. As a native of the area, Virginia claims descent from Whakaotirangi, one of the wives of Hoturoa, the legendary captain of the waka Tainui. (If you have not yet read our post about Hoturoa and the Tainui, you may want to go back and read it now.)

Where Whakaotirangi planted her first crop of taro—or was it kumara?

Whakaotirangi is credited with having brought a basket of either taro or kumara (sweet potatoes) from Hawaiki with her on the Tainui. Stories differ as to which of these root vegetables was in her basket, but she planted one or the other at Pakarikari near Aotea Harbour, thus beginning the cultivation of an important food crop in the land of Aotearoa.

Maketu Marae on Kawhia Harbour

Virginia also led us up to Maketu Marae next to Kawhia Harbour, which is where the Tainui was buried back in the fourteenth century. We were excited for the chance to be invited into this historic marae, and waited patiently in the van just outside the gates for several minutes while Virginia went in and made arrangements for a powhiri (welcome ceremony). When she returned, however, we were disappointed to learn that we would not be able to enter that day after all because the marae was being set up for a big centennial Poukai feast, and everyone was too busy to stop and do a powhiri. Virginia explained that a Poukai is a traditional event that originated as a way for the tribe to show loyalty to the Kingitanga (Maori king movement), and as an opportunity for widows to go before the chief and request aid, but today it has become (to quote Virginia) “an excuse to get together and eat.” Alas, we still did not get to visit the Tainui.

Our meager pipi harvest was supplemented with fresh oysters collected by Davis

Koro cleans the catch

Speaking of eating, it was now past noon and our hosts were eager to get home and start steaming the pipis. Virginia and Koro’s weekend retreat is located on a bluff about a kilometre beyond the marae. In the courtyard, we rinsed the mud off the shellfish and hosed down our sandy feet while Virginia went inside to get the water boiling. Not only did we have a 20-litre bucket half-full of pipis; we also had a couple of 20-litre buckets completely full of rock oysters that Davis had harvested that morning before we arrived.

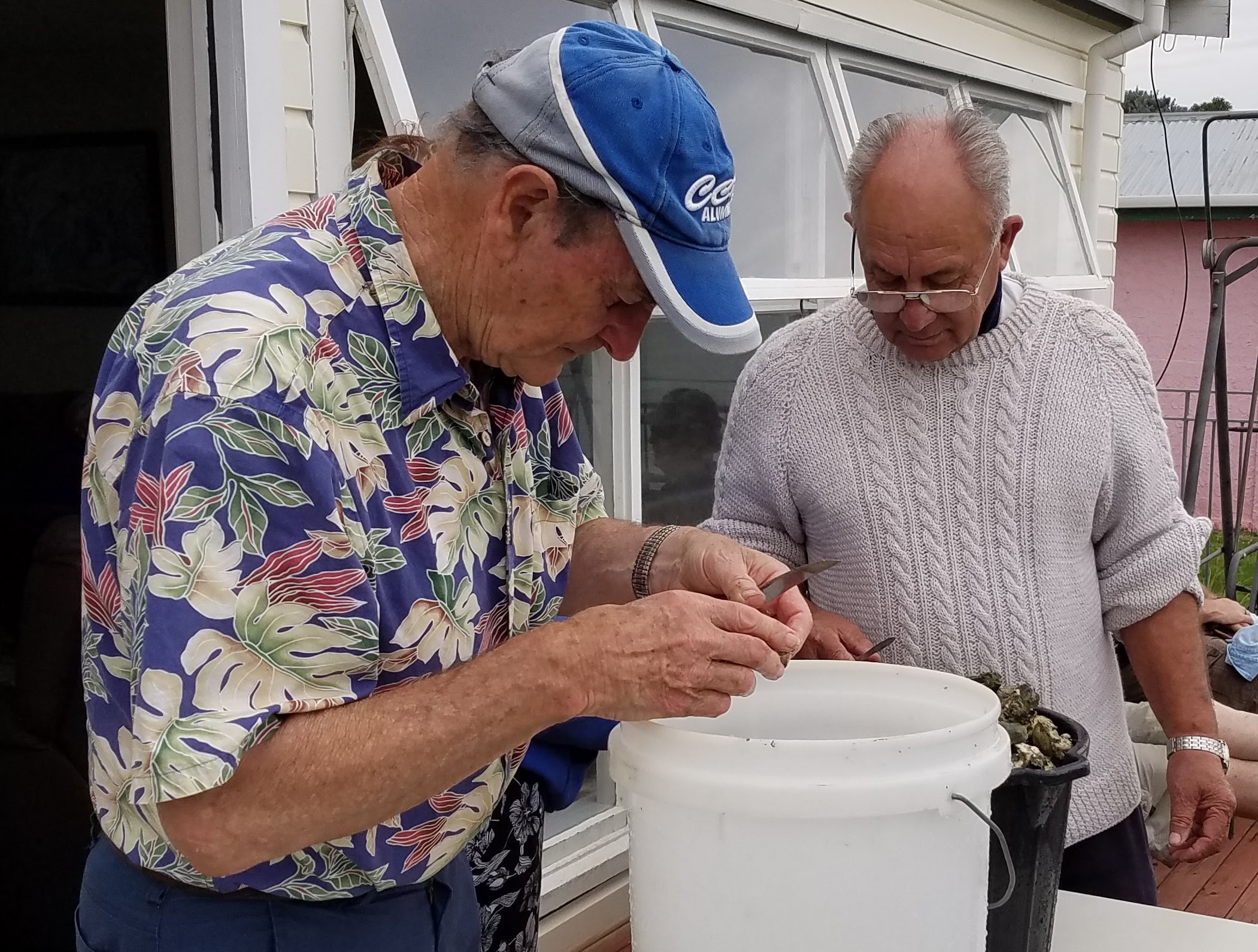

Vic and Bill shucking oysters

Having cleaned off her feet, Nancy went out on the terrace to watch as Davis and Vic broke open the oysters, and then was dismayed when Davis presented her with an oyster-on-the-half-shell and obviously expected her to eat it.

Now, we had been obliged to eat raw oysters fresh out of the sea while visiting Michael’s brother and family in La Rochelle, France, five years ago, and both of us had decided that once was enough. (Click here to see before-swallowing, during-swallowing, and after-swallowing photos from that memorable day.) So Nancy was less than excited about having to try them again, but what could she do? Davis had been so kind to devote his whole day to us that it would have been ungracious to refuse. So she took the oyster and ate it (tolerable, but so salty), and then he handed her another one. So she ate it, too, but when he offered her a third one, she politely declined. Davis laughed.

No silver bells, but plenty of cockleshells

Unhealthy amounts of butter slathered on delicious Maori bread

Eating pipis was different—they were cooked. The little shellfish were so tiny that we had to open dozens to make up an adequate serving, so soon our plates were piled high with empty cockleshells. We filled more plates with the guests’ contributions to the feast—corn on the cob, broccoli salad, cabbage salad, watermelon, and plums—and with thick slices of Virginia’s homemade Maori bread, which she had slathered with heart-stopping amounts of butter.

After we’d already eaten more than our fill and were ready to open the box of cream cheese brownies Michael had made for dessert, Virginia brought out a plate of oysters that she had dipped in a light batter and fried in butter. Curious, we each tried one—and then went back for more. They were delicious!

Alan and Barry relax on the deck overlooking the bay

As we lounged on the terrace overlooking the bay, eating simply prepared fresh food, and swapping stories with people who quickly were becoming dear friends, we wished this afternoon would never end. Eventually, some of us followed Virginia into the kitchen to help her put away the leftovers and wash the dishes. We gladly accepted the bag of uncooked pipis she offered us, looking forward to making some

Peti and Diane on the deck

chowder with them the next day. Sadly, the missionaries said goodbye and climbed back into the van for our journey back to Hamilton.

View of Kawhia Harbour from a lookout in the foothills of Mount Pirongia

On the way home, we stopped at the lookout point at the top of the ridge so that everyone could take a last look at Kawhia Harbour in the distance. A man emerged from the other car parked there, so Wendy and Alan struck up a conversation with him. He said that he ran a motel in Kawhia, and began sharing stories about the area’s legendary history. At one point he stopped and said, “I probably shouldn’t be telling you all this because the Maoris think it’s sacred”—but then he went right on talking, with plenty of encouragement from Wendy and Alan. Michael finally had to interrupt and ask everyone in our party to get back in the van so we could reach civilization before night fell on those winding country roads. Some in the back seats began nodding off, but Nancy helped Michael stay alert by singing a song she and her sister Tracy had performed in a high school production of Carousel long ago:

This was a real nice clambake.

We’re mighty glad we came.

The vittles we et

Were good, you bet!

The company was the same.

Our hearts are warm,

Our bellies are full

And we are feelin’ prime.

This was a real nice clambake

And we all had a real good time!

I’ve wondered about the “cockles of the heart” thing, too, and haven’t found a satisfactory explanation.

Now about Contrary Mary. WARNING: this is not pleasant, and you will never be able to repeat this nursery rhyme again without having horrifying images invade your mind, so you may not want to read on.

***********

The “Mary, Mary” rhyme is said to have originated as a veiled description of Mary Tudor, a.k.a. “Bloody Mary,” the Catholic daughter of Henry VIII and Catherine of Aragon who terrorized English Protestants and executed hundreds of them after she became queen. The growing “garden” thus represents the way cemeteries were filling up. “Silver bells” and “cockleshells” may represent the bells of Catholic cathedrals and the traditional Catholic pilgrimage to Santiago de Compostela in Spain, where the cockleshell symbolized Santiago (St. James). However, other scholars surmise that “silver bells” is a euphemism for thumbscrews and “cockleshells” for similar instruments of torture applied to the genitalia of Mary’s victims. The row of “pretty maids” represents those lining up for the chopping block. Not such a pretty thought. It seems that most of those “nonsensical” Mother Goose rhymes have a dark history that should render them entirely unsuitable for sharing with children.

What a great adventure (especially the quick sand and raw oyster, said by a fellow oyster loather.). I used to wonder what cockles were when my mother would say that something “warmed the cockles of her heart.” Still not sure how that English phrase came into being but it is nice to now know what a cockle is! (And I am still wondering why Mary was so contrary when she had such a nice garden…)

Loved this recount of our gathering.