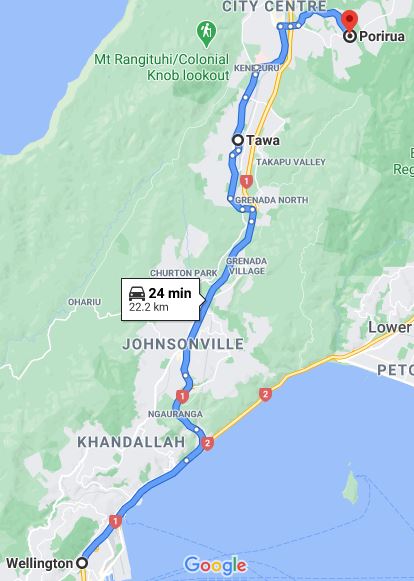

Route to Porirua

After a good night’s rest, we met in the hotel lobby at 8:20 a.m. on Sunday 4 October and drove up Highway 1 to Tawa, a suburb on the north side of Wellington. Several weeks earlier, after Vic and Rangi learned that the rest of the full-time staff of the Matthew Cowley Pacific Church History Centre was planning a trip to the national capital while the museum was closed for the Church’s General Conference, they made their own plans to visit Wellington. Rangi had grown up in nearby Porirua and many of her relatives still live in the area, including her youngest daughter, Hinemoa, so we didn’t expect to see much of Rangi and Vic over the weekend. They had, however, arranged to meet us at the LDS meetinghouse in Tawa, where we all attended sacrament meeting together.

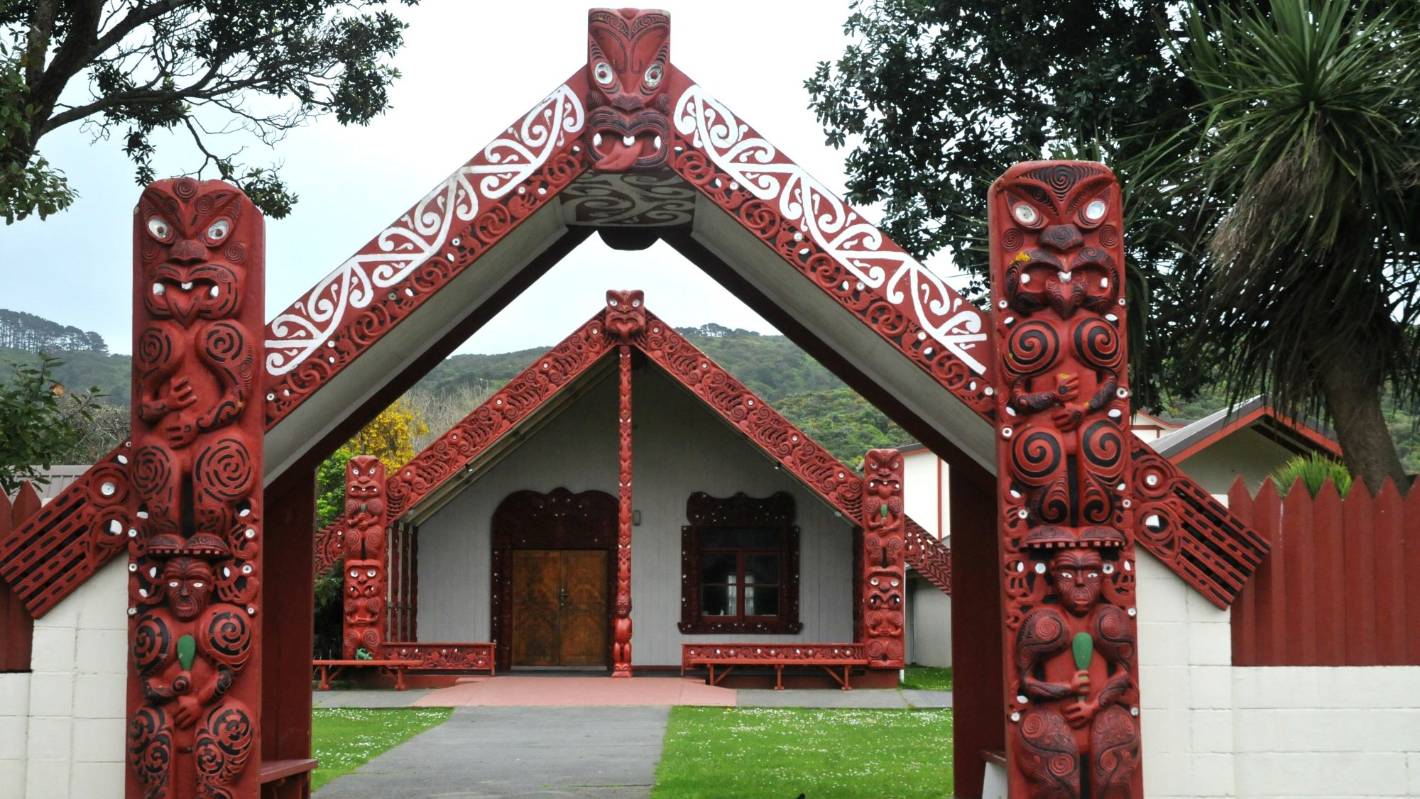

Takapūwāhia Marae, Porirua

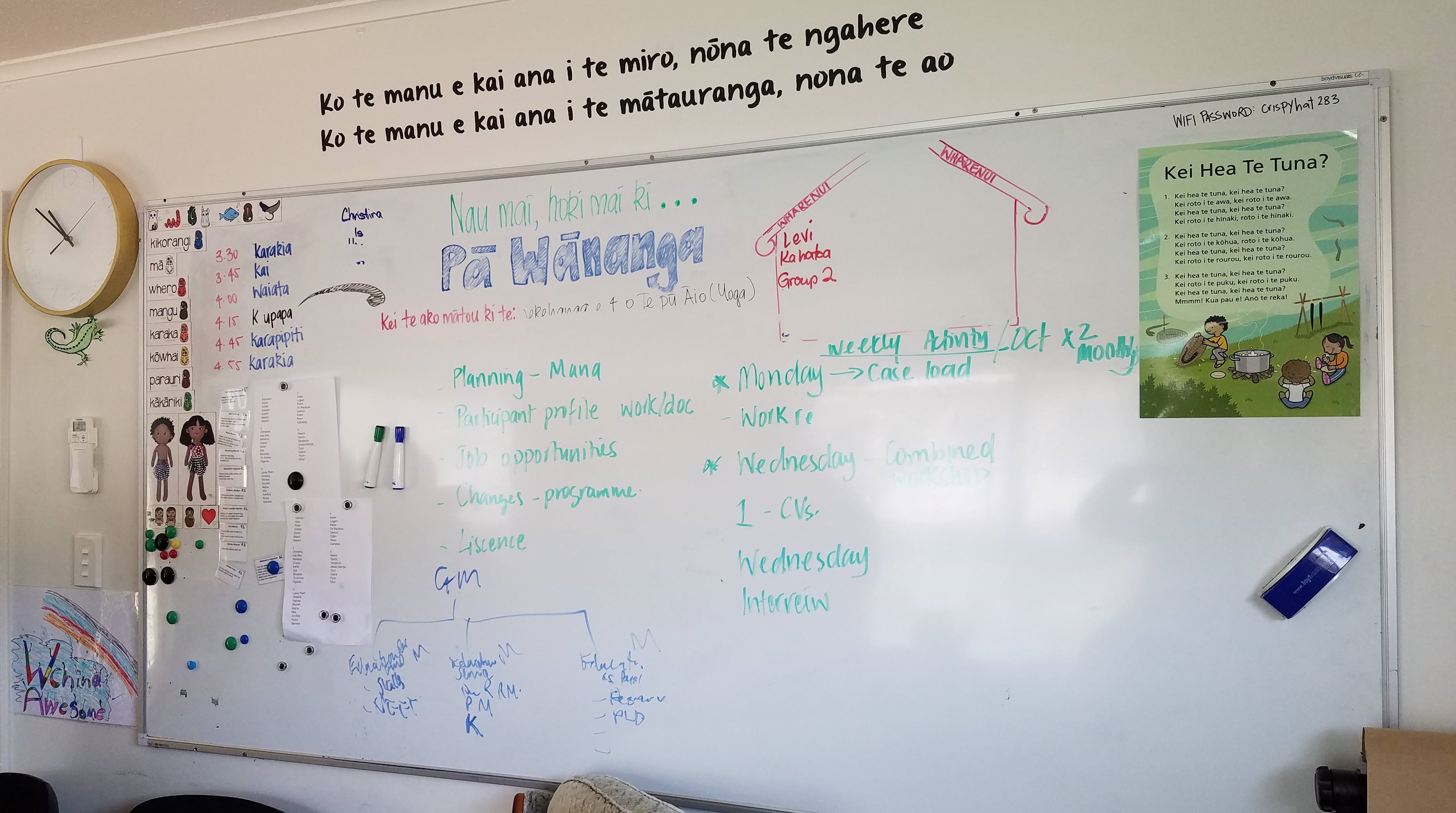

Wendy outside the Māori community education center (pā wānānga) in Porirua

Translation of the proverb above the white board: “The bird who partakes of the miro berry owns the forest; the bird who partakes of education owns the world.”

They also had invited us to go with them to Porirua after church. The plan was to visit the marae (traditional Māori community center) where Rangi’s whānau (extended family) had gathered for generations, and then attend a presentation on the history of her iwi (tribe) prepared by her son-in-law. Unfortunately, someone in the community had just died, and because funerals always take precedence over anything else scheduled at a marae, we were unable to go inside—a disappointment. But Callum had set up his presentation equipment at a nearby Māori education center, so we spent a couple of hours there, learning about the origins of the Ngati Toa and how the tribe had moved south from Kawhia (in the Waikato, not far from Hamilton) during the 1820s amid a series of disputes with neighboring iwi that turned violent. What impressed us most about Callum’s presentation was his obvious passion for his subject. He and Hinemoa are part of the generation that had to learn te reo Māori as adults because their parents and grandparents were discouraged from using the language or practicing many of their cultural traditions. We admire those who have worked hard to reclaim their Māori heritage and share what they’ve learned with others.

American missionaries strolling in Karori Park

The future site of a memorial garden and marker commemorating the first Latter-day Saint baptism in New Zealand

After the presentation, the seven of us American missionaries left Rangi and Vic with their whānau and drove to Karori, a suburb on Wellington’s west side. The stream that runs through the community was the site of the first baptism performed in New Zealand by Latter-day Saint missionaries, and the country’s first LDS congregation was formed there a few months later. That was in 1855; now fast-forward to 2018 or so, when local Church members began seeking permission from community officials and general Church leaders to erect a marker next to the stream where the baptism took place. The exact location of the historic event is uncertain, but it’s thought to be on private land that would be hard for visitors to access, so the Church and the city of Karori have agreed to place the marker on a nice plot at the edge of a public park. On the day we visited, the park was full of families enjoying a pleasant Sunday afternoon, as well as a number of practicing cricket and rugby players.

Te Papa’s atrium

We spent the remainder of the afternoon at the place that had been our primary reason for visiting Wellington: a special exhibit at Te Papa, New Zealand’s National Museum, called Gallipoli: The Scale of Our War. Barry and Eva had seen the exhibit in 2019 and told the rest of us that it was not to be missed; now we understand why. But before we describe the show and our reaction to it, we need to give some historical background: The Gallipoli Peninsula in western Turkey was the site of a major World War I campaign in which military forces from Russia, France, and Great Britain (including Australia and New Zealand) attempted to wrest control of the Dardanelles and the Bosphorus—crucial waterways for international trade—from the Ottoman Empire. The campaign, which dragged on for eight months, was an utter disaster for everyone involved. Half a million casualties were almost equally divided between the sides, including more than 113,000 deaths from a horrific combination of injury, illness, exposure, and starvation. New Zealand’s death toll was 3,431, which may not sound like much until you consider that the number represents more than 20 percent of its fighting force. Over 4,100 additional Kiwis were wounded. Ultimately, the Entente nations pulled out, leaving the Ottomans in control of the Turkish straits—although the war, exacerbated by internal strife, soon led to the Empire’s complete collapse. Russia, France, and Great Britain achieved almost nothing from the Gallipoli campaign, but the effort had a significant, lasting effect on Australia and New Zealand. With the Australia and New Zealand Army Corps (ANZAC) having been regarded as a full, valued participant in the military operation, the soldiers and citizens of those respective countries began regarding themselves as legitimate players on the world stage. Gallipoli thus became a touchstone of national pride for both South Pacific nations, and the anniversary of the Gallipoli landing—25 April—has become both countries’ most revered holiday.

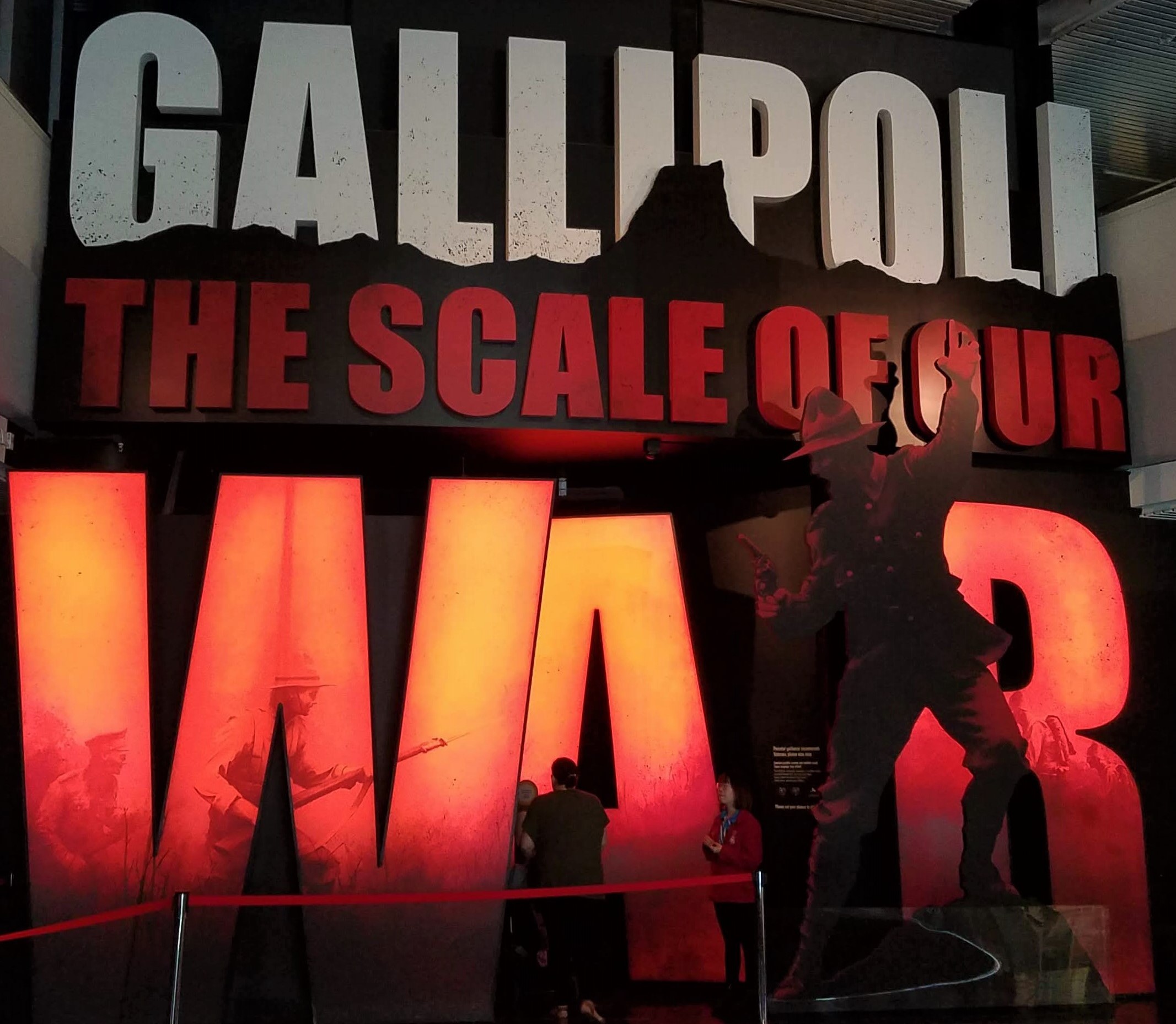

Entrance to the exhibit

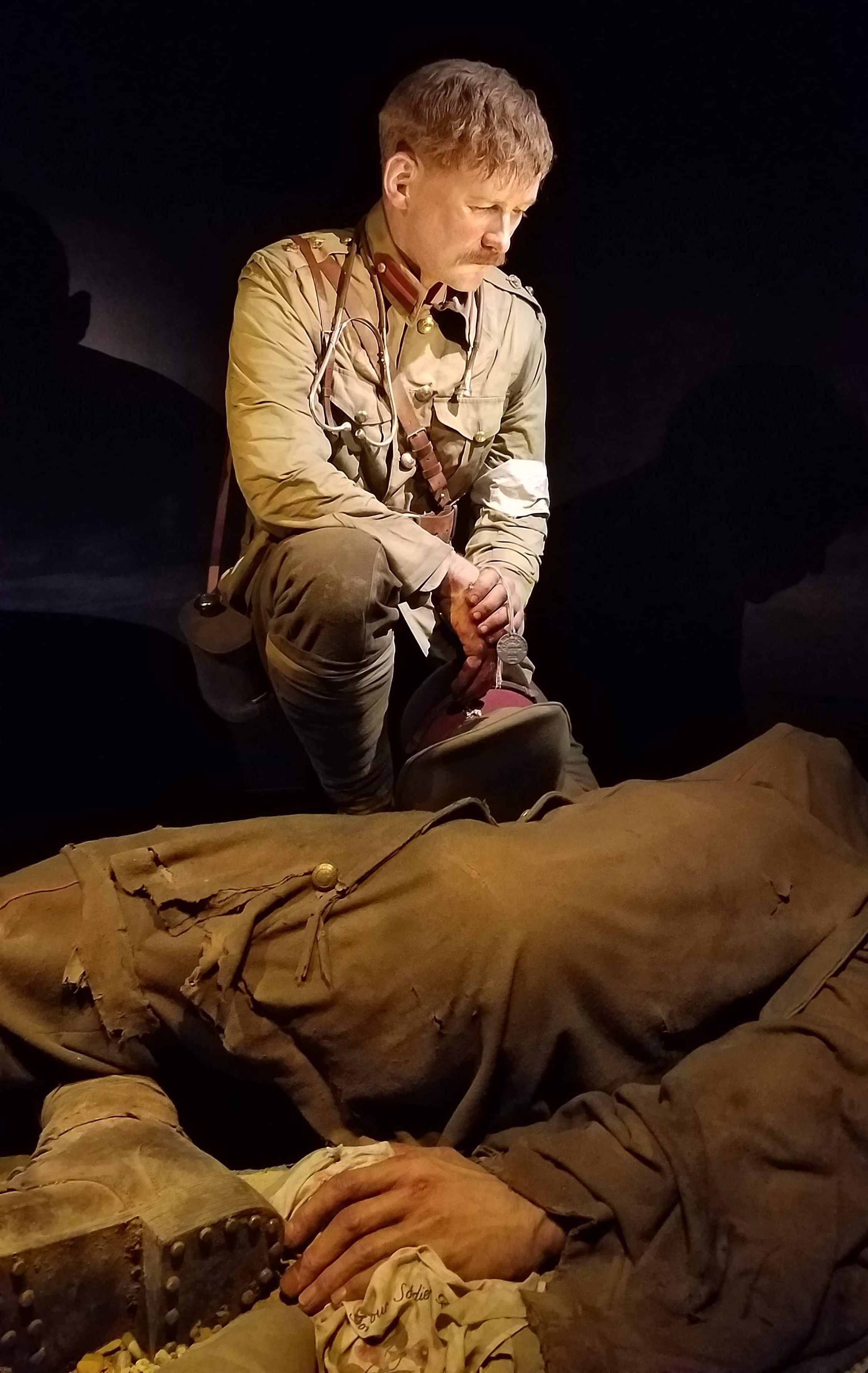

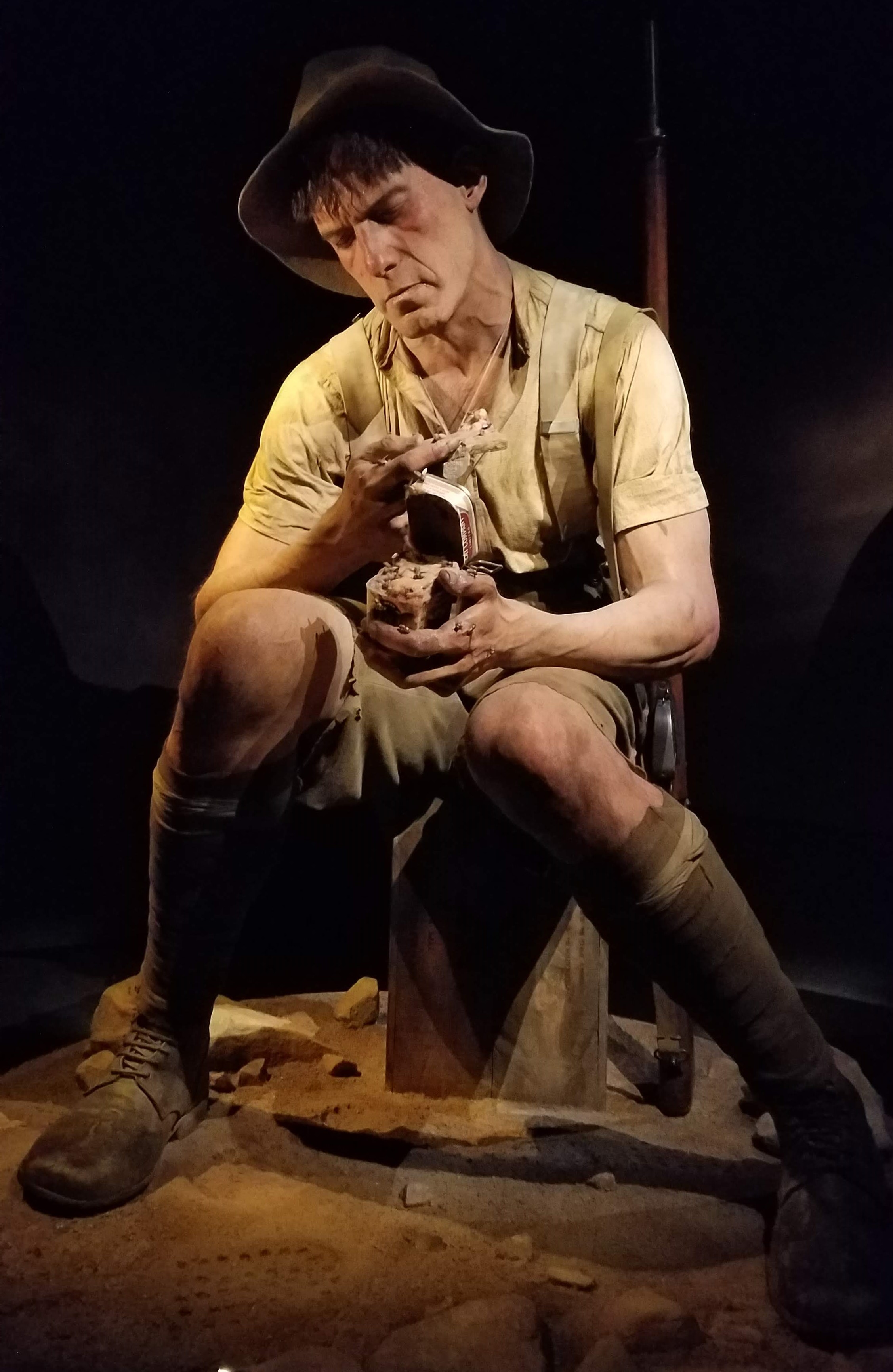

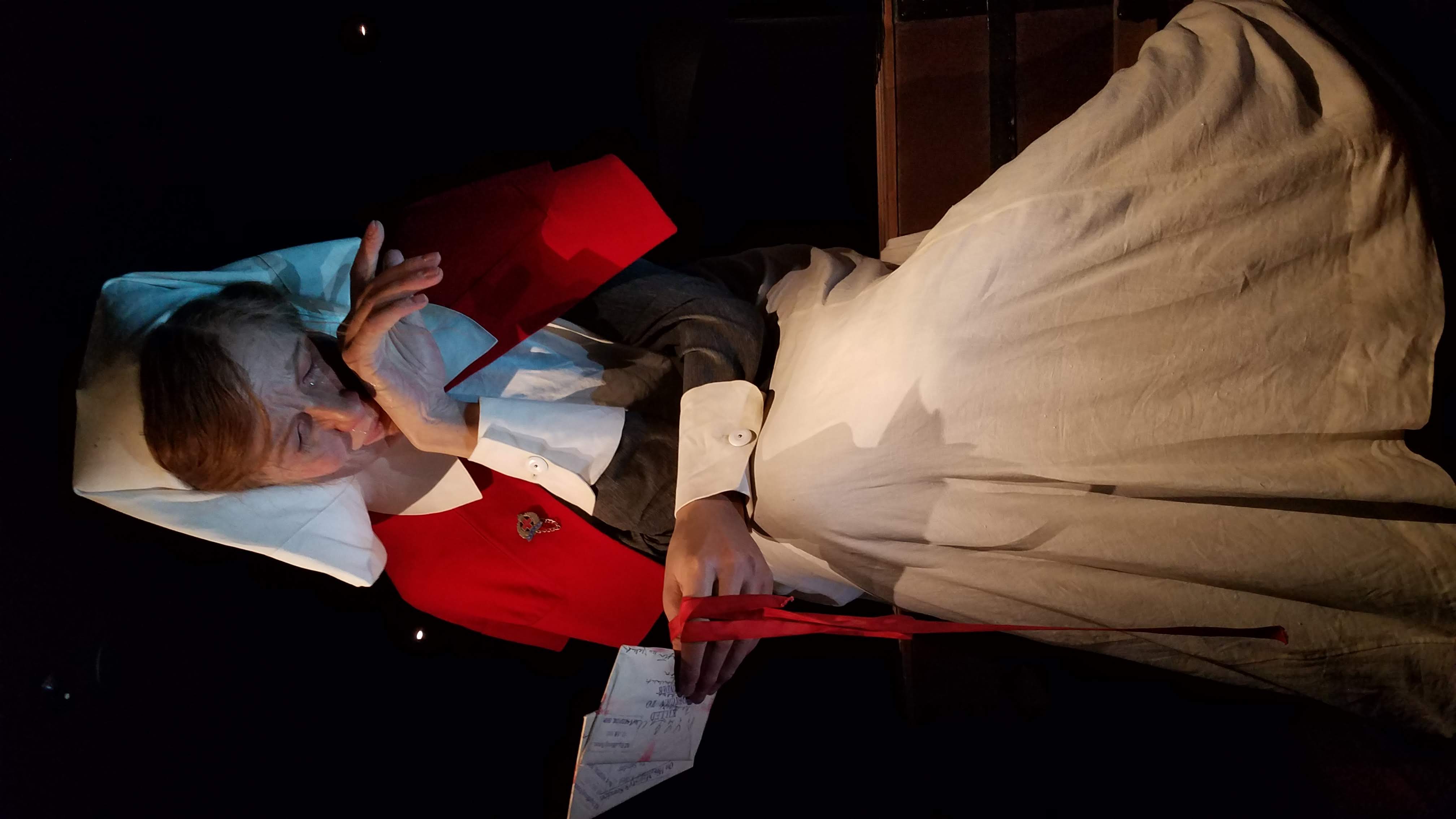

Now back to the exhibit at Te Papa. Its title, Gallipoli: The Scale of Our War, gives a hint of what makes the show so stunning. The exhibit features six dramatic dioramas containing lifelike, minutely detailed figures of ANZAC soldiers and medical personnel—at a scale 2.5 times normal size. The dioramas were created by Wētā Workshop (the wizards behind Peter Jackson’s fantasy films), and their effect is truly overwhelming. Each tableau, whose figures represent actual people, is accompanied by the stories of those individuals, both in written text and dramatized audio recordings, based on diaries and letters written either by the people themselves or others who knew them. The stories are so poignant that one cannot help but be moved to tears. The pictures we’ve included here (along with quotes from the narration) fail to convey the exhibit’s sense of scale and thus cannot possibly do it justice, but they at least provide a glimpse of what we experienced. The show, which also includes a number of artifacts, short films, and a wealth of interpretive material, was so impressive that we wanted to absorb it all, but the experience was so intense and emotionally draining that after about an hour and a half we simply had to leave. Why must so many lives and so much potential be lost to war? Why can’t humankind let love prevail so we can break free from this cycle of destruction?

Lieutenant Spencer Westmacott, age 29, “was one of our first men to land on Gallipoli on April 25th. He scrambled up a ridge and led us to a hill called Baby 700, shouting ‘Good boys! Good lads!’ At Baby 700, he reinforced the Australian line, but his right arm was smashed by a bullet while holding off a Turkish attack. He was stretchered to the beach and evacuated that night.”

Lieutenant Colonel Percival Fenwick, age 46, “was one of our first doctors ashore. In the next god-awful 24 hours, he treated hundreds of us Anzacs on the beach. Fenwick was no stranger to the battlefield—he’d served in South Africa 15 years before—but this was a different sort of war. He set up a casualty station and did his best to sort out systems and get us more supplies. But endless hours treating the sick and wounded took their toll. He was shipped out, ill and exhausted, after two months—in Gallipoli terms, a lifetime.”

Private Jack Dunn, age 26, served as a machine gunner. “A keen athlete and fitter than most, he had rushed to enlist, but contracted pneumonia after the first brutal month of fighting. When he returned from hospital—still pretty crook—the poor bugger fell asleep at his post and was sentenced to death for endangering his unit. It could have been any of us. Jack was game to the core, unflinching in the face of fire. The General eventually took his reputation and illness into account and sent him back to the front line.”

Private Rikihana Carkeek, age 25, of the Māori Contingent was part of a machine-gun unit surrounded by Turks during the August 1915 attack on Chunuk Bair. “Bullets seemed to be whizzing and sputtering from all sides, right, left and front,” he wrote in his diary. “Our officer, Lieutenant Waldren, was shot and fell back amongst us in a heap. He managed to say, ‘Carry on, boys,’ and then died.” Carkeek himself was shot through the body at the base of his neck, but managed to drag himself to the beach and was evacuated to a hospital ship. Most of his unit did not survive.

Staff Nurse Lottie Le Gallais, age 33, was stationed aboard the hospital ship Maheno, which set out from Wellington in July 1915. She hoped to meet up with her brother Leddie, who was stuck on Gallipoli, but their paths would never cross. In November, all Lottie’s letters to Leddie came back to her. An official black stamp read: “Killed, return to sender.” He’d been dead four months, but only family back home had received the news. Lottie wrote: “So there it is. No mistake. Leddie is dead. I felt sick.”

Model of the hospital ship Maheno

Sergeant Cecil Malthus, age 26, survived the Battle of Gallipolis and was shipped to France were he fought in the Battle of the Somme—the first large-scale action in France for a New Zealander. In a letter to his sweetheart, Hazel Watters, he described his experiences in that action as “a taste of hell.” He was wounded while deepening a trench when his shovel hit an unexploded bomb. Luckily the shovel took most of the force but his right foot was shattered. This injury meant he was declared unfit for service in December 1916. Three months later, in March, he arrived home to Timaru.

To find some relief, we went upstairs to the permanent Māori collection on the fourth floor, where we found the answers to several questions we had had about the history and culture of New Zealand’s native people. We learned, for example, that the sails of traditional waka (canoes) were made not from canvas, but from coarsely-woven reeds and flax. Pataka (storehouses) were tapu (sacred) to Māori because stored food represented not only the community’s ability to survive, but also its ability to provide an appropriately gracious welcome to visitors. We also learned about the history of poi, a traditional dance form in which small woven balls attached to the end of a cord are twirled in rhythmic, symbolic patterns. The dance was originally developed as a means of providing an audible rhythmic beat to keep a team of rowers in sync. Poi also provides exercise to increase strength and flexibility in the hands and arms and improve coordination—useful skills for both combat and craftsmanship. (Unfortunately, we were not allowed to photograph anything in the historic Māori collection.)

Te Hono ki Hawaiki, a symbolic link to the Māori’s ancestral home

The Ranginui door represents the Sky Father revealing the world of light to his children gathered on earth

While many of the items on display in the museum are from earlier centuries, many represent more contemporary interpretations of Māori cultural traditions. One that particularly impressed us (and which we were allowed to photograph) was Te Hono ki Hawaiki, the whare (meetinghouse) of Te Papa’s marae, a large gathering space located at the back of the museum. The name of the whare refers to the legendary homeland of New Zealand’s Māori, and its whakairo (decorative carvings) symbolically relate the whakapapa (genealogy) of the country’s major tribes.

Left to right at Indian Alley before dinner was served: Michael, Eva, Diane, Wendy, Alan, and Barry. (As is often the case, Nancy was behind the camera.)

Our group reconvened in the museum’s atrium at 5:30 p.m. and then walked a few blocks from there to Indian Alley for dinner. Our selections, served family-style, included Parda Biryani, a traditional dish of rice, meat, and vegetables steamed in a casserole under a piece of naan; it looked almost like a pot pie. We also shared Lamb Rara (a spicy dish from northern India combining lamb chunks and mince with a yogurt-based sauce); Mango Chicken, Diwani Handi (chopped spinach and other vegetables with “smoky aromas”), and several types of naan.

So many choices at Kaffee Eis

“Indian Summer” gelato. The best flavor ever!

We left thinking we were too full for dessert but changed our minds when we passed a couple on the street who were eating ice cream. They pointed us toward Kaffee Eis, a full-store version of the gelato stand we had seen on the wharf the day before. Nancy had what she still claims is the best gelato flavor she has ever tasted: “Indian Summer,” a sublime mixture of ginger, cardamom, and turmeric in a yogurt base. (We’re going to have to try recreating that one at home!)

Diane with some of our Quiddler words

Barry and Eva consider the hands they were dealt

Back at the Intercontinental Hotel, we finished the evening playing Quiddler in a corner of the lounge. Wendy had borrowed the game from her cousin, who is serving a mission in Wellington. Nancy thought that since the object is to create words from the cards in your hand, she would have a better chance of winning than she usually has with number-based games like Farkle. Alas, the game still involves the element of chance; she lost abysmally.

If she lost abysmally, at least Nancy had the best gelato ever! The Gallipoli exhibit sounds amazing in spite of its emotional toll on viewers. Truly, why must we keep on fighting each other?