(Note: if you are reading this on a mobile phone, be sure to swipe left and right to view all photos.)

So how do a couple of over-60-year-olds spend three days in Paris?

L’ hébergement (Lodging)

First, you find a great place to stay, close enough to the Gare du Nord so you can schlep your own luggage, and near a Metro stop or two. (But is any place in Paris not near a Metro stop?)

How does a flat across the street from the Mairie of the 10th Arrondissement sound? Idéal.

The apartment on Rue du Faubourg Saint-Martin is owned and usually occupied by a woman named Nathalie, but when Nathalie travels (such as when she goes to Nice for a few weeks in July and August), she lets it out to people like us, using Airbnb. So we have a large, comfortable bedroom; a spacious living room, a den, two toilets and a bathtub, plus a full kitchen and dining area. Nathalie has excellent taste—as well as a stunning collection of ceramics and other objets d’art that she apparently picked up in travels around the world.

Nathalie chez elle |

Private collection of objets d’art |

Airy bedroom |

Nathalie’s toilette-bibliotèque could supply a course in classic European literature |

View from the toilette (if you don’t have your nose in a book) |

Mairie of the 10th arrondissement |

Children’s formalwear boutique down the street |

A classic Art Nouveau Metro station sign |

Port Saint-Martin, one of the original gates into Paris |

La nourriture (Food)

Fortunately, Paris is one of those places where you have to try hard to find a bad place to eat. We found some pretty good ones in Nathalie’s quartier, and more farther afield. Here’s where we ate for three days:

Le petit déjeuner (Breakfast)

Bo & Mie Boulangerie, 359 Rue du Faubourg Saint-Martin |

Bo & Mie’s array of creative baked goods |

La Petite Louise, 65 Rue du Faubourg Saint-Martin |

La Petite Louise: yogurt and freshly squeezed orange juice |

Le Pain des Copains, 96 Rue du Faubourg Saint-Martin |

Nancy awaits her quiche, hot chocolate, and tasty breads at Le Pain des Copains |

Le déjeuner (Lunch)

Wanted Café, 70 Rue du Faubourg Saint-Martin |

Wanted Café: gazpacho and summer salad |

Desserts at Wanted Café: citron crumble with spiced ice cream, and tapioca with coconut sorbet and pineapple |

Restaurant du Musée d’Orsay, 1 Rue de la Légion d’Honneur |

Restaurant Musée d’Orsay: entrecôte |

Musée d’Orsay: ravioli |

Merci Jerome, 12 Quai de la Mégisserie |

Merci Jerome’s ready-to-eat options |

Merci Jerome’s dessert options |

Le diner (Dinner)

Le Sanglier Bleu, 102 Bd de Clichy |

Entrée at Le Sanglier Bleu: multicolored tomatoes with feta and basil sorbet |

Le Sanglier Bleu, main plate: sea bream with sautéed vegetables |

Le Sanglier Bleu, main plate: risotto with peas and parmesan |

Dessert at Le Sanglier Bleu: peaches with white wine gelatin and ice Verveine |

Le Sanglier Bleu, dessert: crème brulée with berries |

24 Le Restaurant, 24 Rue Jean Mermoz |

24 Le Restaurant, entrée: watermelon salad |

24 Le Restaurant, main plate: grilled dorado with courgettes |

245 Le Restaurant, main plate: dahl with spinach, mushrooms, and sweet potato chips |

24 Le Restaurant, dessert: grilled apricots with panna cotta and pistachio cream |

24 Le Restaurant, dessert: caramelized apple crumble with lemon cream and apple sorbet |

Le Parisien Saint-Martin, 337 Rue Saint-Martin |

Le Parisien: tomato and chèvre risotto |

Le Parisien: Croque Monsieur with salad and frites |

Sights Worth Seeing Again

Everyone who has been to Paris has his or her favorite spots. These were at the top of our must-visit-again list:

Musée d’Orsay

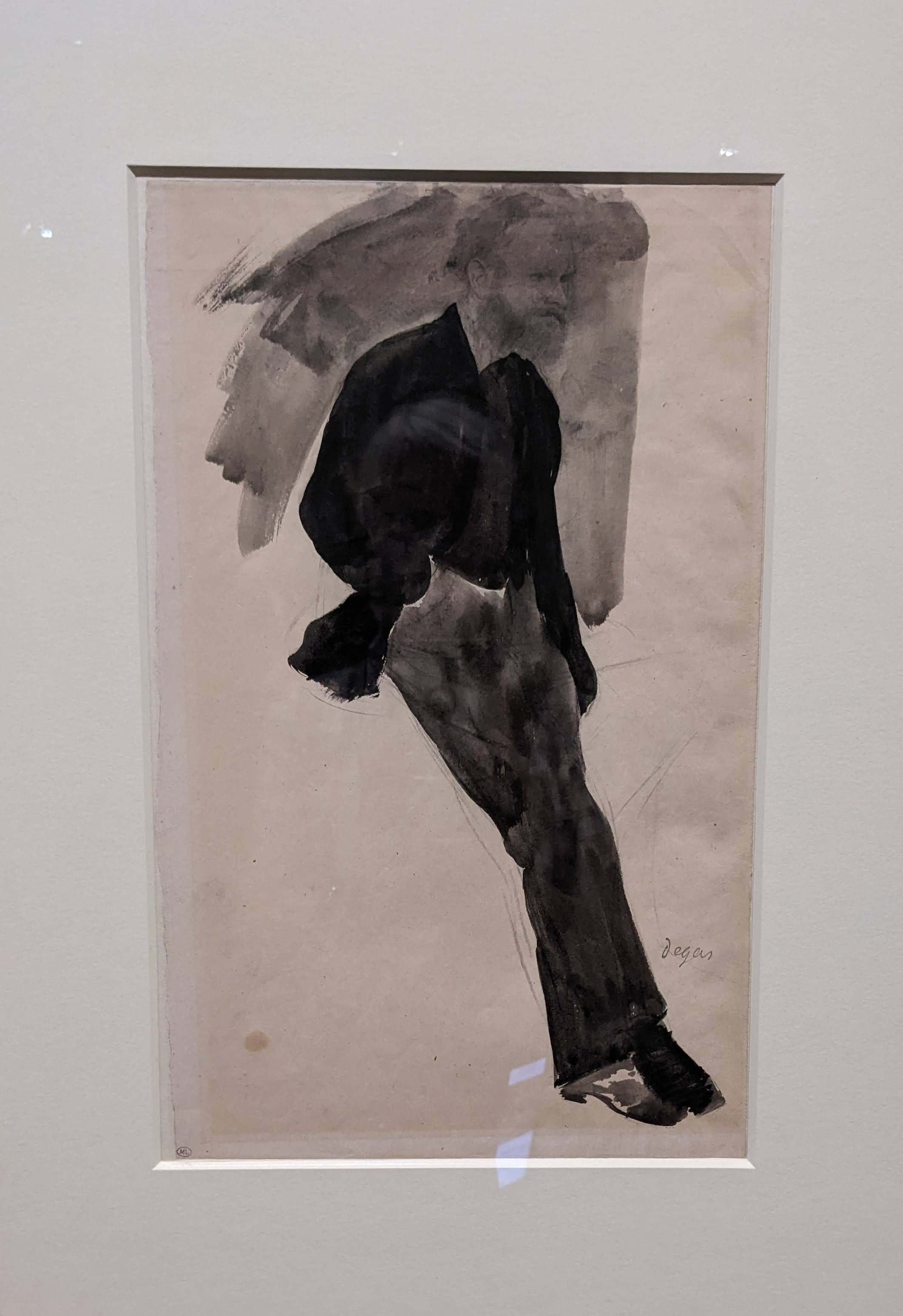

Indubitaly, the Louvre is the largest and most famous art museum in Paris. But let’s face it: unless you reside in Paris and have a pass that will get you in as many times as you want, the Louvre is just too overwhelming. The next most famous art museum in Paris is the Musée d’Orsay, which houses France’s national collection of art from the mid-nineteenth century to the beginning of the twentieth. The Musée d’Orsay did not exist in 1978, when we had the opportunity to live in Paris long enough to visit the Louvre repeatedly. At that time, the Louvre’s Impressionist collection was crammed into the Jeu de Paume (formerly the royal tennis courts) and the Gare d’Orsay was an abandoned train station. Transforming the gare into a musée (a project completed in 1986) was a brilliant move. We had visited the d’Orsay with our children in 1993, but most kids under the age of fourteen don’t want to spend much time in a museum where the displays aren’t interactive and you can’t touch anything except the stair rails. So we were eager to go back, and we were delighted to discover that we would be in town at the right time to see a special exhibit featuring works by Édouard Manet and Edgar Degas. What made the show especially interesting was that it focused on the influence the two artists had on one another, and allowed us to see each in a whole new light. The audio tour was very helpful, but we had to elbow our way through hordes of visitors to get a good look at the paintings. The museum does require reservations to control the number of people entering at any given time, but apparently they don’t require anyone to leave before the next group is allowed in.

Great Hall of the Musée d’Orsay |

Édouard Manet, self portrait, 1878 |

Edgar Degas, self portrait, 1855 |

Manet’s portrait of his parents, 1860 |

Manet, Portrait of his wife, 1874 |

Degas’s watercolor sketch of Manet, c. 1860 |

Degas’s portrait of his grandfather, 1857 |

Degas, Blue Dancers, c. 1893 |

Degas, Woman Ironing, 1873 |

Degas, Portrait of Madame Yves Gobillard, née Morisot, 1869. The Morisot sisters were an important part of this circle of artistic friends |

Manet, Portrait of Berthe Morisot, 1873 |

Berthe Morisot, Le Berceau (The Cradle), 1872 |

Manet, The Monet Family in their garden, 1874 |

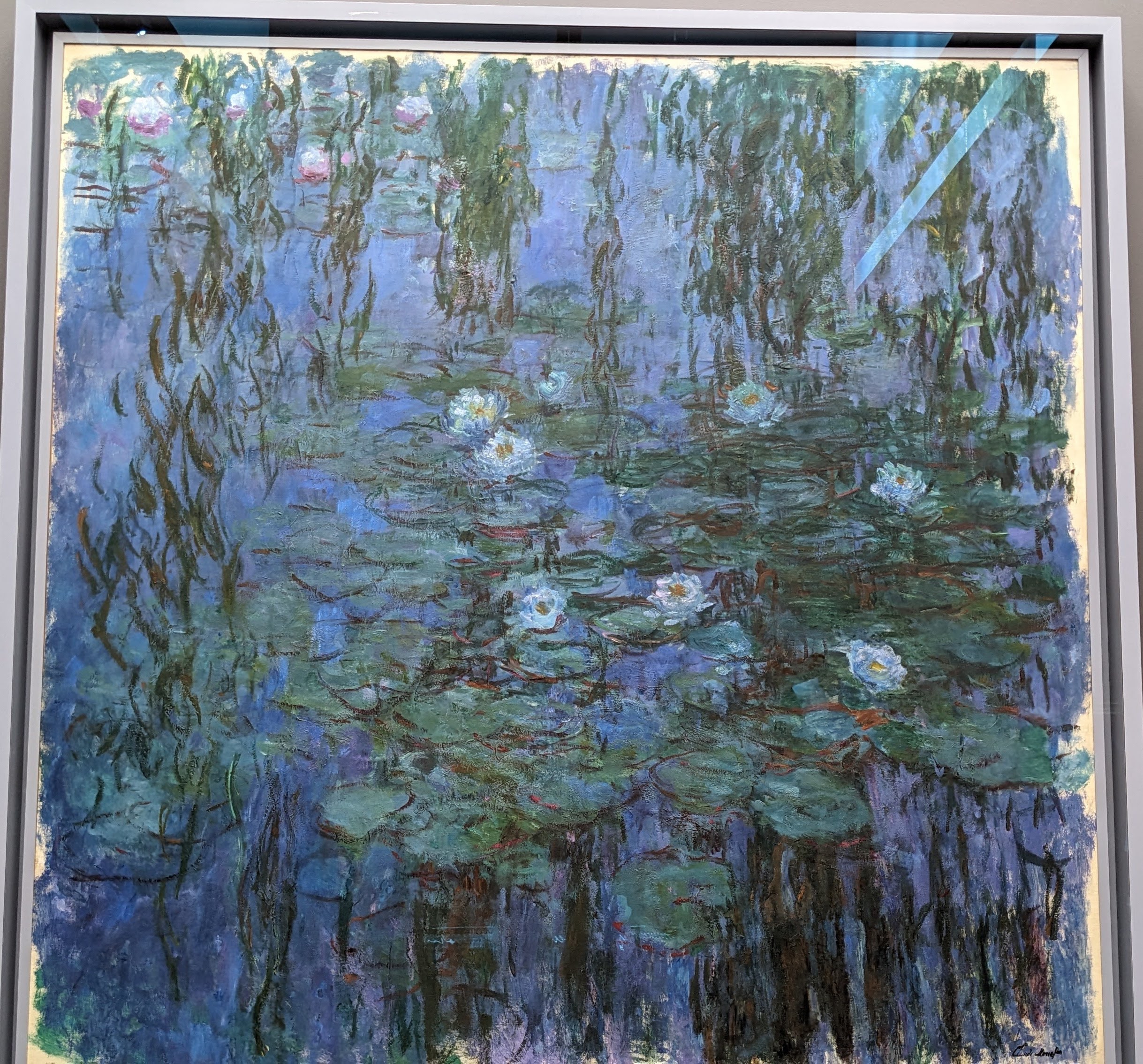

Monet, Blue Water Lilies, 1916-1919 |

Monet, Water Lily Pond, Harmony Rose, 1900 |

Paul Gauguin, Ararea (Joys), 1892 |

Toulouse-Lautrec, Seule (Alone), 1896 |

Van Gogh, Bedroom at Arles, 1889 (one of three almost identical paintings; others are in Amsterdam and Chicago) |

Notre-Dame de Paris and Île de la Cité

In April 2019, we were horrified (along with the rest of the world) to learn that the wooden roof of Notre-Dame de Paris had caught fire and collapsed, taking the spire with it. It wasn’t the first time the famous cathedral had suffered extensive damage since the first iteration was completed in 1260. Time and weather took their toll, of course, necessitating the removal of the original spire in 1786, but human disregard was responsible for more serious destruction. During the reign of Louis XIV, some of the medieval stained glass was removed, and a pillar in the main portal was torn out to allow noblemen’s carriages to enter the building. The revolutionaries who overthrew the French monarchy in 1789 were not kind to the cathedral, either, melting down its bells to make cannons and smashing many of its statues in their anti-royalist, anti-Catholic fervor. Parisians began to pay more attention to what they were losing after Victor Hugo published The Hunchback of Notre-Dame in 1831, leading to a major restoration effort in the mid-nineteenth century. Thirty-year-old architect Eugène Viollet-le-Duc was chosen to direct the restoration project, which kept him occupied for twenty-five years. A thoughtful designer and meticulous worker, Viollet-le-Duc was careful to maintain the medieval character of the building while strengthening its structural elements.

As we stood in front of the cathedral on the Île de la Cité a few days after Paris’s Bastille Day celebrations (which we missed because we were in Norway), we felt sad about what had been lost, but hopeful about the restoration. After the fire, architects from around the world responded to the French prime minister’s call for “fresh ideas” for rebuilding the roof and spire. Some suggested that modern techniques and fireproof materials (glass, maybe?) could be employed while still paying homage to Viollet-le-duc’s nineteenth-century design. Others proposed more futuristic, fantastical schemes: one imagined a shiny gold spire resembling the flames that consumed the wooden one, while another envisioned a shaft of light shooting into the sky from the point where the spire had stood. One thought it would be a great idea to turn the roof into a swimming pool. But public sentiment was on the side of tradition, and France’s General Assembly ruled that the restoration must preserve the building’s historic character. Therefore, while one crew worked to stabilize the cathedral’s underlying stone structure, a crew of expert craftsmen began painstakingly reproducing the roof’s oak lattice using hand tools and medieval woodworking techniques. President Emmanuel Macron vowed to rebuild Notre-Dame de Paris “more beautifully” than ever, and within five years (presumably, in time to greet the crowds coming to Paris for the 2024 Olympics). Although he’s unlikely to completely fulfill that rash promise, we could see that a lot of progress had been made by July 2023, and officials insist that the cathedral will be ready to reopen in December 2024. The world will be watching.

Notre-Dame’s façade did not suffer much damage in the fire |

The transept (the center section surrounded by scaffolding) and the flying buttresses supporting the nave have to be stabilzed before the roof can be replaced |

Virgin of Paris is temporarily on display outside the cathedral |

Charlemagne and His Guards by Louis and Charles Rochel, 1878 |

Conciergerie, former courthouse and prison |

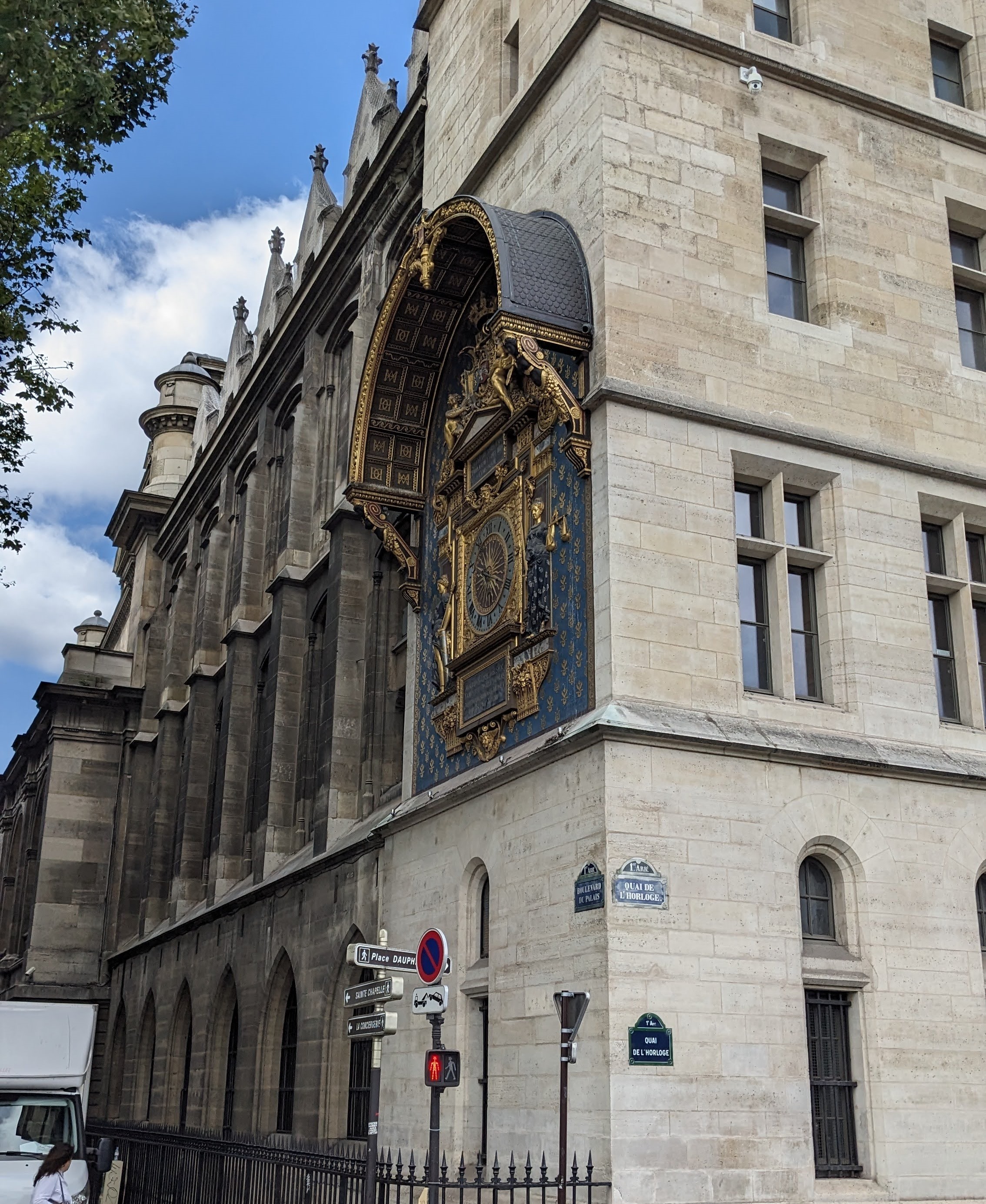

The clock tower at Palais de la Cité actually told the correct time |

Sainte-Chapelle

While Notre-Dame de Paris was the cathedral of the people—“Our Lady”—the much smaller Sainte-Chapelle was the exclusive “Holy Chapel” of royalty, part of the palace complex when French kings lived on the Île de la Cité. Sainte-Chapelle was commissioned in 1238 by Louis IX (aka Saint Louis) as a worthy sanctuary for the Crown of Thorns supposedly retrieved from the head of Christ following his crucifixion. Comprising two floors, the upper chapel was reserved for the royal family and their guests, and was where the ornate silver reliquary containing the Crown of Thorns was kept. The lower level was a place of worship for courtiers, servants, and the palace guard.

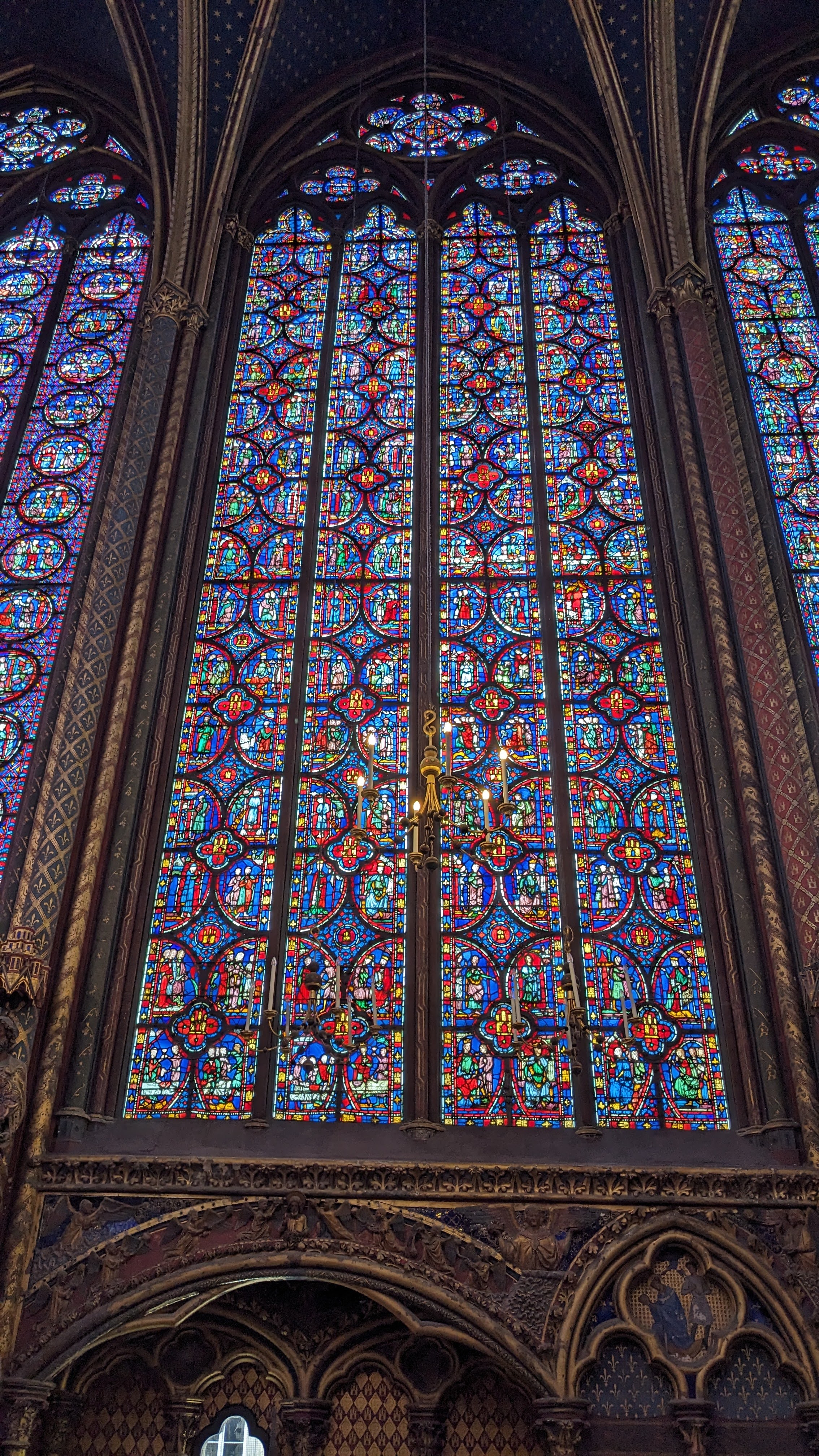

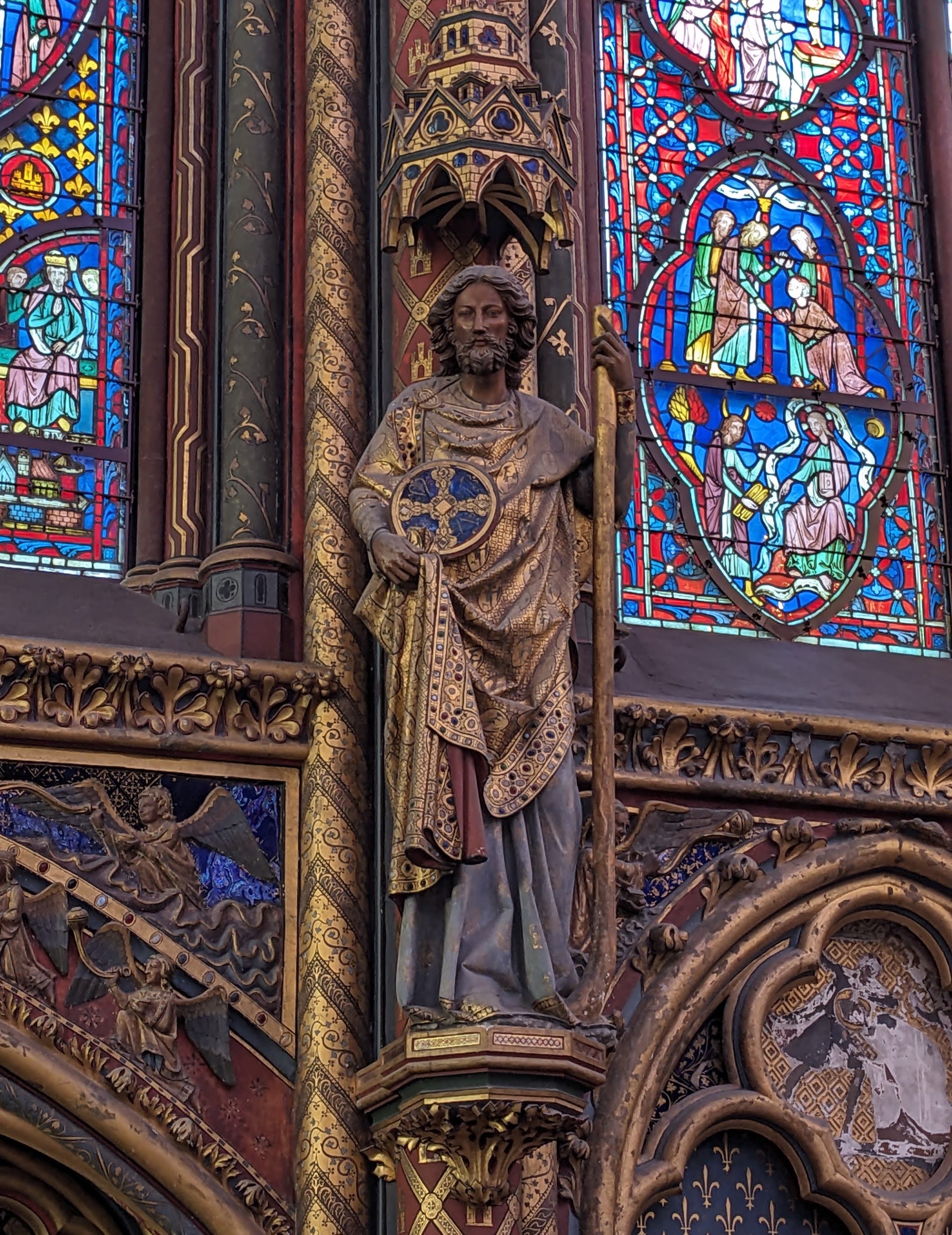

Today, visitors to the lower chapel might be completely captivated by the golden vaulting that supports a ceiling resembling a glorious, star-spangled sky, but when those visitors ascend a narrow spiral staircase to the upper chapel, they will suddenly understand how the word breathtaking entered the language. There’s another starry sky overhead, but this one is held up by fifteen arches filled with glowing, jewel-toned glass. A closer look reveals myriad biblical scenes depicted in the glass—1113, to be exact—telling stories from the Creation to the Apocalypse, graphic novel-style. (We wish we had thought to bring binoculars!) What visitors will not see in the upper chapel, however, is the Crown of Thorns or any other Christian relics, which were relocated to the treasury of Notre-Dame in the wake of the French Revolution. Like those of the cathedral, some of Sainte-Chapelle’s sculptures and stained-glass windows were vandalized in the 1790s and the building put to more prosaic purposes, but—miraculously—nearly two-thirds of the original stained glass survived. The building was fully restored during the same period as Notre-Dame. During World War II, the glass was removed and stored in a safe place until the conflict ended; since then, various protective layers have been applied to the glass to preserve it for future generations. Despite the standing-room-only crowd with whom we shared the space during this visit, our souls were stirred by this incomparable gem of medieval art and craftsmanship.

Sainte-Chapelle |

Sainte-Chapelle, upper level |

Sainte-Chapelle, lower level |

Stained glass is the glory of Sainte-Chapelle |

Sainte-Chapelle’s rose window |

An apostle, one of the twelve “pillars of the Church.” The window to the right depicts the story of God appearing to Moses in the burning bush |

Louis IX’s fleur-de-lys and castle motifs appear in a relief sculpture on Sainte-Chapelle’s exterior |

… and on painted columns inside |

Archangel Michael atop Sainte-Chapelle |

What a wonderful way to round out your European vacation! Paris is always enchanting and you seem to have taken full advantage of its charm, it’s delicious food those sights special to you both. Awaiting partie deux!

So beautiful–your favorite places to revisit in Paris coincide with mine. Sainte-Chappelle is one of the great treasures of the world, a truly celestial place. Caiti and I had a great time at the Musee d’Orsay and are so glad we climbed to the top of Notre Dame (this was in 2005). Cathedrals, gardens, museums (and yummy restaurants)–some of the great reasons to pack your bags and get on a plane. Although Geirangerfjord is my most hopeful idea of the celestial kingdom. Thank you for sharing; look forward to more.

What a wonderful visual tour your have given us! Thank you so much for sharing again.