When Michael planned the schedule for this trip, he did not include attendance at a formal church service on the itinerary for Sunday 27 December, assuming that we could hold an informal devotional and gospel discussion in the car during the three-hour drive from Dunedin to Invercargill. Diane, Eva, and Barry had not made the same assumption, however. They reasoned that because on Sunday morning we would be in Dunedin, a city with a sizable Latter-day Saint population, we shouldn’t have trouble finding a place to attend a one-hour sacrament meeting before getting on the road. They thus came prepared to attend church even though “church” was not on Michael’s “Schedule of Known Events.” Michael and Nancy (who understood that if Michael had intended for us to attend sacrament meeting, he would have included the start time and the address of the meetinghouse on the spreadsheet) didn’t realize that there was a discrepancy between their assumption and that of the rest of the group until Saturday evening, when the subject came up over dinner. After a brief discussion, we all agreed that it would be nice to attend sacrament meeting on Sunday morning, and that there should be enough time to do so if we skipped going out for breakfast. From the Church’s website we determined that the Dunedin 1st Ward met at 9:00 a.m. at a chapel that turned out to be less than five minutes away from our motel, so there really was no reason not to attend sacrament meeting—except for one thing: Unlike Diane, Eva, and Barry, neither Nancy nor Michael had brought anything appropriate to wear to church. Could a full-time missionary Sister be forgiven for wearing pants, and a full-time Elder an open-collared sport shirt to sacrament meeting? We decided that the Lord would rather see us at church in too-casual clothing than see us sitting outside in the car just because we hadn’t brought a skirt or a tie, so in we went.

When Michael planned the schedule for this trip, he did not include attendance at a formal church service on the itinerary for Sunday 27 December, assuming that we could hold an informal devotional and gospel discussion in the car during the three-hour drive from Dunedin to Invercargill. Diane, Eva, and Barry had not made the same assumption, however. They reasoned that because on Sunday morning we would be in Dunedin, a city with a sizable Latter-day Saint population, we shouldn’t have trouble finding a place to attend a one-hour sacrament meeting before getting on the road. They thus came prepared to attend church even though “church” was not on Michael’s “Schedule of Known Events.” Michael and Nancy (who understood that if Michael had intended for us to attend sacrament meeting, he would have included the start time and the address of the meetinghouse on the spreadsheet) didn’t realize that there was a discrepancy between their assumption and that of the rest of the group until Saturday evening, when the subject came up over dinner. After a brief discussion, we all agreed that it would be nice to attend sacrament meeting on Sunday morning, and that there should be enough time to do so if we skipped going out for breakfast. From the Church’s website we determined that the Dunedin 1st Ward met at 9:00 a.m. at a chapel that turned out to be less than five minutes away from our motel, so there really was no reason not to attend sacrament meeting—except for one thing: Unlike Diane, Eva, and Barry, neither Nancy nor Michael had brought anything appropriate to wear to church. Could a full-time missionary Sister be forgiven for wearing pants, and a full-time Elder an open-collared sport shirt to sacrament meeting? We decided that the Lord would rather see us at church in too-casual clothing than see us sitting outside in the car just because we hadn’t brought a skirt or a tie, so in we went.

Dunedin 1st Ward meetinghouse

View of Dunedin from the carpark of the LDS meetinghouse

We were well rewarded for attending. The Dunedin chapel was perched high atop a hill affording a beautiful view of the city and environs, but it was the talks that really held our interest. The first speaker, Sister M, began by stating that her text was taken from her favorite book of scripture: Ecclesiastes. Perhaps it is not unusual to hear a Protestant or Catholic name Ecclesiastes as their favorite Bible book, but for a Latter-day Saint, it’s practically unheard of because few of us want to believe that “all is vanity.” But this woman proceeded to explain that the true message of the book is that life is meaningless only if we try to leave God out of it. As the Preacher saith, “the conclusion of the matter” is this: “Fear God, and keep his commandments, for this is the duty of mankind” (Ecclesiastes 12:13, NIV). We can testify that our lives have become more meaningful as we have sought to know the Lord’s will for us and follow the counsel we have received.

The other speaker—Bea, the bishop’s wife—shared some experiences about the blessings that have come to her as she, too, listened for the voice of the Lord and heeded his words. One example: when Bea was thirteen years old and in the class that put together her school yearbook, she was inspired to ask her teacher if they could include a picture of a girl who should have been a classmate but wasn’t, because the girl had disappeared six years earlier. To many people in the community, this girl had simply become “a face on the milk carton,” but to Bea, she was a missing friend who needed to be remembered. As she worked with her teacher to create an age-progression photo of the girl for the yearbook, she gained a greater understanding of Heavenly Father’s love for his children. “He knows each of us,” she testified. “No one is forgotten, and he will speak to us personally if we will open our hearts to him.”

The spirit of the meeting had been so edifying that we weren’t in a hurry for it to end, but were pleased nonetheless when the closing prayer finished at 9:50, allowing us ten extra minutes to thank the speakers, say goodbye, and then hurry back to the motel so that Diane, Eva, and Barry could change from their church clothes into traveling clothes before we checked out.

View of the Pacific Ocean from the other side of Highcliff Road

View of Otago Harbour from one side Highcliff Road

The reason for concern about the time was that we had booked an 11:00 tour at the Royal Albatross Centre at Taiaroa Head, the wild and exposed eastern tip of the Otago Peninsula. We hadn’t realized beforehand that the 45-minute drive along the narrow peninsula’s aptly named Highcliff Road would offer such breathtaking ridge-top views of Otago Harbour below us on the left, and the Pacific Ocean below us on the right.

Larnach Castle

William Larnach

Smack in the center of the peninsula is Larnach Castle, New Zealand’s only palace. The road didn’t pass close enough for us to actually see the estate, but we were intrigued by its history: The extravagant residence, which resembles the Gilded Age mansions of Newport, Rhode Island, was built in the 1870s by an Australian banker and land speculator who eventually became a member of the New Zealand Parliament. William Larnach’s story has some obvious parallels to that of a certain American businessman-politician of our own time. Despite boasting that “he had never failed in anything he tried,” his fortune was never quite as large as he claimed and many suspected that his business dealings were not always above-board. Indeed, Larnach may have gone into politics as a means of keeping his mind off his failing investments. Te Ara, The Encyclopedia of New Zealand, reports that Larnach’s “need to maintain at any cost a show of material success, and to hide any trace of weakness or self-doubt, was a ruling instinct which exacted a heavy toll on his personal happiness.” In 1898, when bankruptcy loomed along with the possible loss of his Parliament seat, Larnach went into an empty Parliament committee room, locked the door, and shot himself. Eight years later, his palatial home was sold to the government for use as a mental hospital. Eventually the estate passed into private hands and sat derelict until 1967, when an American couple bought it, restored the house and grounds, and turned the place into a tourist attraction with luxury accommodations. We kind of wish we had had time to stop, but we didn’t want to miss our audience with more legitimate royalty.

Royal Albatross Centre

The royal albatross’s wing span can reach 10 feet

In the case of the Royal Albatross Centre, royal refers to a species of albatross, not the House of Windsor. The royal albatross and a similar species, the wandering albatross, are the world’s largest seabirds, with wingspans reaching 3 metres (10 feet) or beyond, and weights up to 10 kilos (22 pounds). (For comparison, the largest seagulls have a wingspan of about 1.7 metres [5.5 feet] and weigh about 1.75 kilos [3.8 pounds].) These birds spend most of their lives at sea, rarely even touching land except to breed. The royal albatross plies the Pacific Ocean off the coast of Chile, searching for fish and squid. Each bird flies an estimated 118,000 miles (190,000 kilometres) a year—more than eight times the number the average American adds to the odometer in the same period. We asked our guide at the RAC how the birds rest if they land so infrequently; she explained that albatross can sleep while soaring, sort of going on autopilot.

Nesting albatross

The Chatham Islands lie east of Christchurch

Most albatross nest on remote islands where few humans ever see them, so Dunedin’s Taiaroa Head is truly unique: it’s the home of the only mainland royal albatross breeding colony in the world. Breeding birds arrive here on the Otago Peninsula in September. They nest during early November and by December have laid their eggs: only one per pair, once every two years. Parents take turns sitting on the egg and then flying off for food during the 80-day incubation period, and then they trade off guarding the chicks for another 35 days after they hatch around the end of January. What we observed on 27 December was nine big birds seated on the hillside below the observation enclosure, only a few of the estimated two hundred individuals that breed here. Occasionally, one bird would briefly stand up and reposition itself before settling on the ground again, and once we saw the “changing of the guard” between a male and a female—but we couldn’t tell which was which. (Unless they do a DNA test, the resident ornithologists can’t tell the difference, either.)

After 35 days of constant care, the parents begin leaving the chick more and more on its own, returning with food only every few days. The fluffy juveniles need eight more months of development before they are ready to take to the air, usually in September. Soon thereafter, the flock will leave Taiaroa Head, vacating the nesting area for the next breeding group. The young birds will spend the next three to five years at sea, never touching land until they are ready to join the breeding adults who return to Taiaroa Head to repeat the cycle. The only other breeding ground for the royal albatross is on the Chatham Islands, about 800 kilometres (500 miles) east of the South Island. (The archipelago is an administrative unit of New Zealand, though a world apart, with unique flora and fauna and the Moriori, an ethnic group with its own language and culture.)

Red-billed gull and its chick

Spotted Shag colony

The albatross of Taiaroa Head share the tip of the Otago Peninsula with approximately 4,000 red-billed gulls, which we found to be fearless around humans and borderline annoying. They congregate on the eastern slope of the headland, while the albatross occupy the northern slope. Also on the north is a colony of spotted shags, a species of cormorant native to New Zealand. All three types of birds were nesting, but we could see hatchlings only among some of the gulls and shags.

Taiaroa Head underground fortress

These jail cells held prisoners in solitary confinement

A rough stockade surrounds the site of the old Māori pa

Taiaroa Head is also the site of an underground fort, built in the late nineteenth century to protect Dunedin from possible invasion by the Russian Navy. Sadly, we did not have time to avail ourselves of the opportunity to see the only restored 1886 Armstrong Disappearing Gun in the world, nor to learn exactly how Fort Taiaroa functioned during World War II, but we did get to see the 1880s-era jail where prisoners housed next to the army barracks could be put into solitary confinement. Long before the fort was built, the headland had been the site of a strategic Māori pa (fortified village), as well as a lighthouse to guide ships into Otago Harbour.

Red-billed gulls roosted on our van while we toured the Royal Albatross Centre

By the time our tour was over, we were ready for lunch—especially since we had skipped breakfast. The Toroa Café, conveniently located at the RAC, had an empty table, so we placed our orders and sat down.

Toroa Cafe

Caramel slice from the café

Tautuku Bay

Fortified with pumpkin soup, chicken-bacon salad, and a caramel slice, we began the four-hour drive to Invercargill, leaving State Highway 1 at Balclutha to follow the Southern Scenic Route along the coast through the Catlins. Scenic it was! Every now and then someone would call out, “Pull over! We’ve got to get a photo of this!” From the Florence Hill Lookout near Papatowai we got a stunning view of the pristine beach at Tautuku Bay. This is the only place left on the east coast of the South Island where native old-growth forest extends from the hilltops all the way down to the shoreline; some of the trees in this area are more than a thousand years old. Although there is a footpath down the hill to the beach, today it appeared as though the white sand had never known a human footprint.

Our audio companion

Besides enjoying the scenery, we took advantage of quiet time in the van to begin listening to an audio recording of A Man Called Ove by Fredrik Backman, which Eva happened to have on the old iPod that also contains all her music. By the time we got to Invercargill we had heard only a few chapters, but enough to wonder why Eva had recommended this particular book to us as “sweet and funny.” Ove was a curmudgeonly middle-aged widower who seemed to spend most of his time contemplating ways to commit suicide—as soon as he could ensure that every detail of his meticulously ordered life had been seen to. We hadn’t expected Eva to regard such sardonic humor as “sweet,” but reserved judgment until we had heard more of the story.

The Oreti River cuts through the flat plains of the Southland region

Invercargill, at the mouth of the Oreti River, is situated on the sea at the edge of the wide, flat plain that makes up much of the south end of the South Island. The plain’s alluvial soil is some of New Zealand’s most fertile, so it supports a lot of small-to-medium-size farms, mostly devoted to producing meat, dairy products, and animal feed. We noticed many herds of domesticated deer grazing along the road in addition to cattle and sheep.

Cornerstone New Life Church has taken over the Classical-Victorian-style Bank of New Zealand building at a major Invercargill intersection

Four modern columns provide a striking focal point for Invercargill’s Dee Street, but the city’s Heritage Commission cited them as “detracting from the heritage character” of the district

Quest Serviced Apartments

Neither of us had any preconceived mental images of what the city of Invercargill would look like, so we can’t exactly say we were disappointed, but we weren’t enamored, either. As we drove into town on the Southern Scenic Route and turned the corner onto Dee Street/Highway 1, the slant of the early evening sun cast buildings on the west side into deep shadow while throwing harsh light onto facades on the east, unmitigated by trees or any other vegetation. Invercargill not only lacks the kind of dramatic natural beauty that had entranced us in both Christchurch and Dunedin, but it also seems somewhat run-down. Michael said it reminded him of Hamilton, Ohio (the town he worked in when we moved to Cincinnati in 1996, not to be confused with Hamilton, New Zealand, where we now reside). Invercargill and Hamilton, Ohio, have roughly the same population (50-60,000), enjoyed a period of prosperity from the late nineteenth century into the twentieth, and now betray signs of similar economic decline. Today the streets of both towns are marred by a lot of empty storefronts, but both municipalities have made a valiant attempt to revitalize their central business districts, commissioning street art and restoring and repurposing attractive historic buildings.

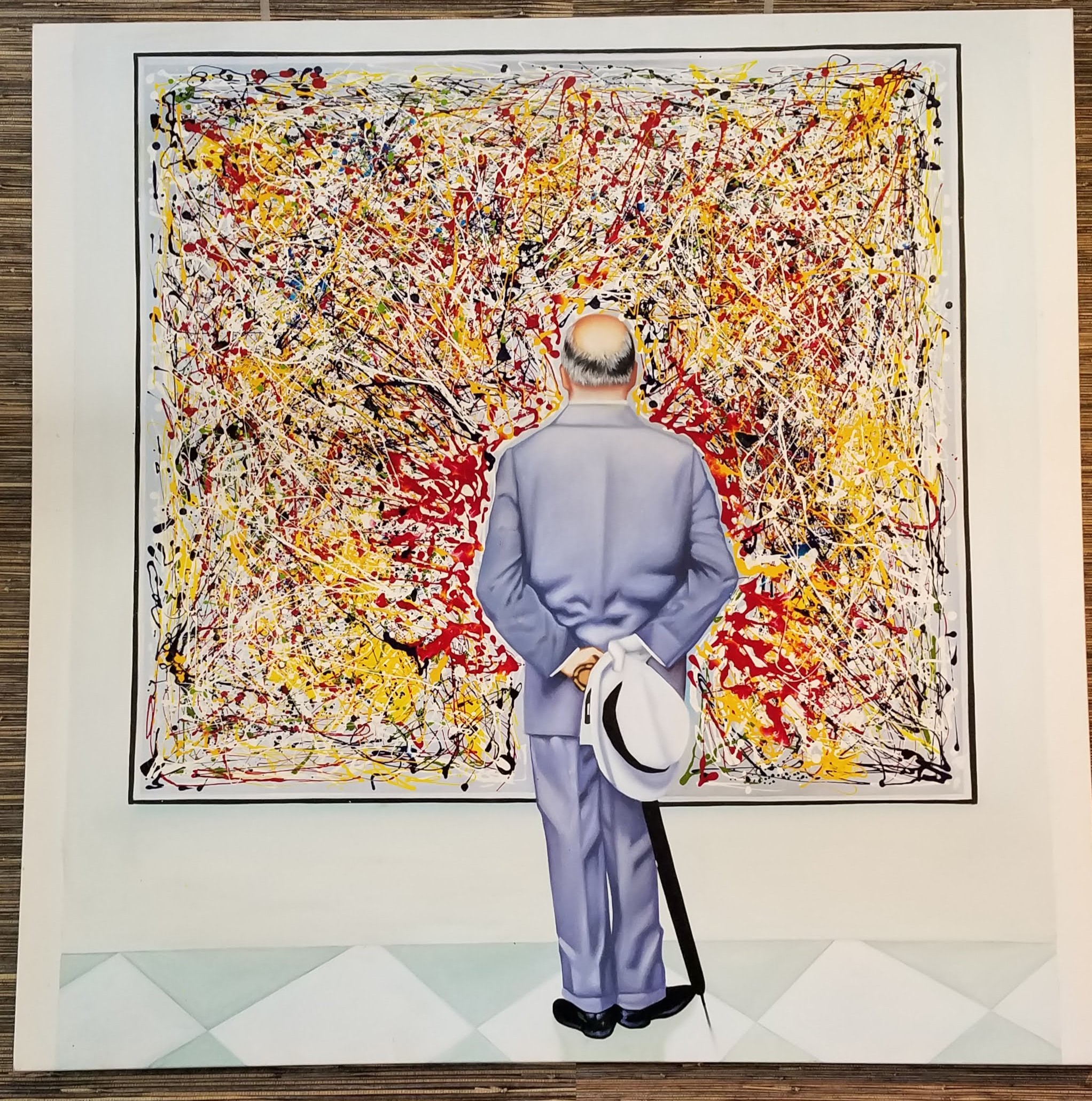

One example of the unique artwork on display in the Quest Invercargill

Welcome to Thai Poal

The Quest Serviced Apartments where we would stay for the next two nights is in one of those repurposed buildings, the Art Deco-International-style former post office transformed into modern, well-maintained, comfortable accommodations. Because we arrived after hours (i.e. after 4:00 on a Sunday evening), we were let inside by a remote operator with whom we communicated via an intercom outside the front door. On the desk inside we found prepared packets containing our room keys and guest instructions. We never saw any hotel staff behind the reception desk or anywhere else in the building during our whole stay.

After allowing ourselves about half an hour to settle into our rooms, we reconvened in the lobby and then walked down the street to Thai Opal, the restaurant where we shared a family-style Asian meal. We ordered enough different curries and stir-fries to satisfy all five of us, but not so many that we had to leave any food behind (a balance we often fail to strike). The last thing we ordered was a plate of mango sticky rice with ice cream—and five spoons.

Leave A Comment