Design

Modular wall panels introduce the exhibit and display stories about The Call and The Construction Camp

With the story content for each thematic section of the Sacrifice and Consecration exhibit taking shape, it was time to bring in a professional designer from the Church History Museum. By the end of June 2020, Wayne had produced a preliminary design that pleased everyone: clean, bright, and inviting, with each of the three sections distinguished by a different color. Stories and images would be displayed on a set of modular wall panels in the middle of the spacious gallery, as well as on the 4-metre-high walls on either side. Another key element was a video kiosk where visitors could view short clips from the labor missionaries’ recorded interviews. In addition, there would be two display cases: one with “smart glass” to regulate light exposure on fragile documents and historic artifacts, and another with conventional Plexiglas for less-sensitive objects and facsimiles.

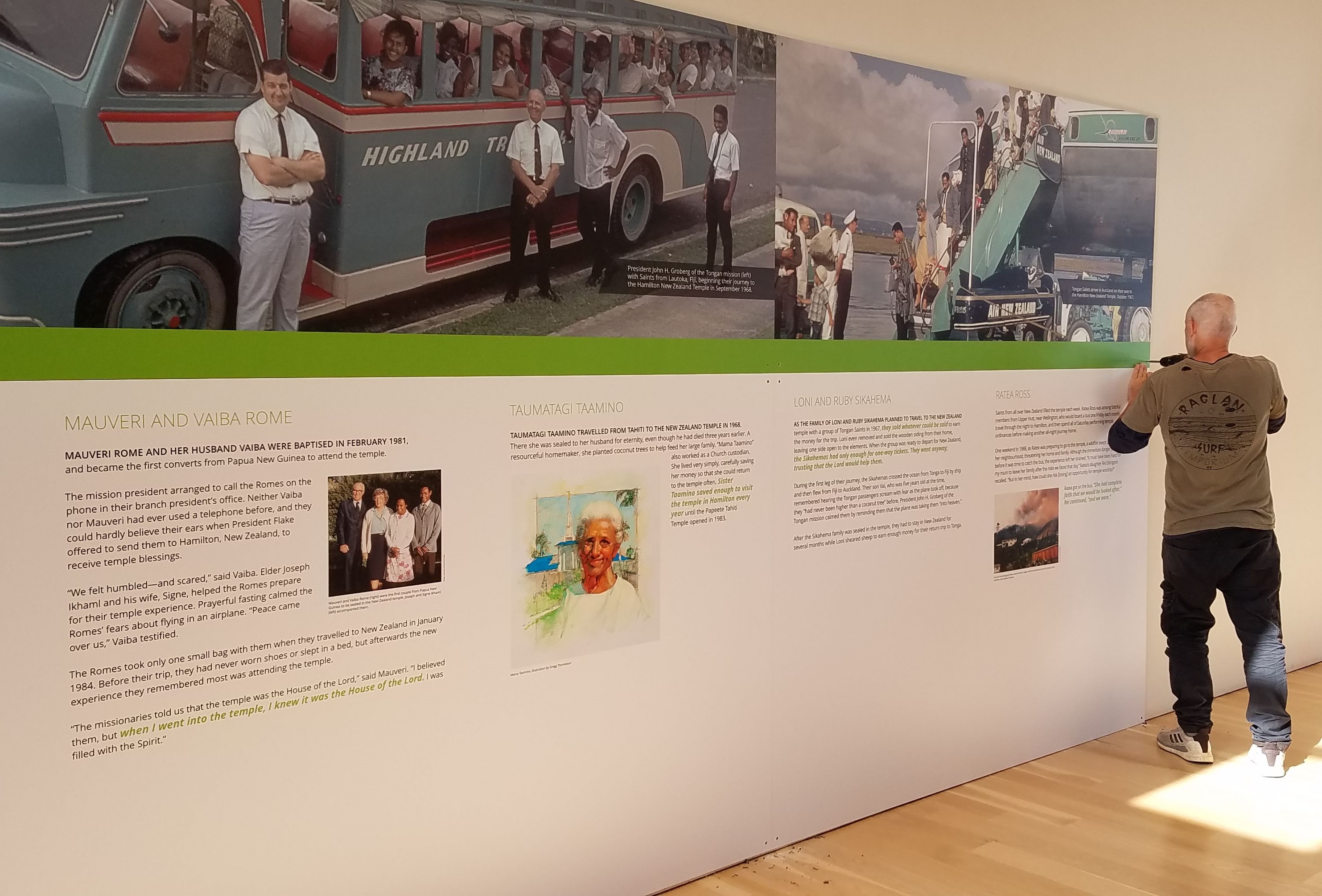

An enlargement of the group photo taken after the temple’s cornerstone ceremony fills an entire wall

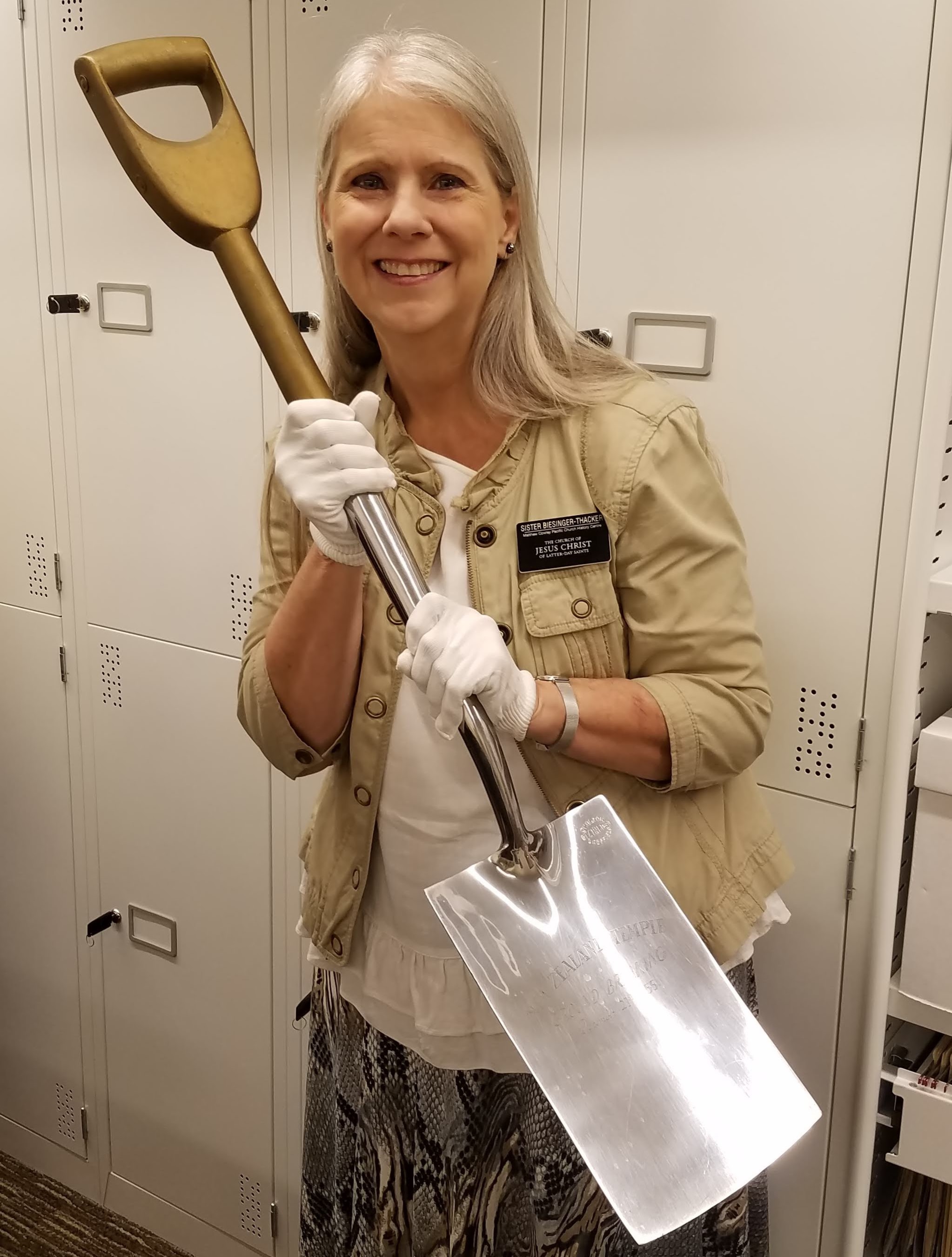

One of the artifacts we really hoped to be able to display was a shovel used to break ground for the temple. The only problem was that all three shovels had been taken to the U.S. by the men who ceremonially turned the soil—the mission president, the head of the Church Building Committee, and the construction supervisor—and not one has since been acquired by the Church History Department. However, we knew where to find the one that went home with the construction supervisor, Elder B: his daughter, our colleague Sister T, told us that her brother had it on display at his home in Utah.

“Do you think he’d be willing to lend it to the museum for a couple years?” Eva asked.

“No way!” Wendy exclaimed. “That shovel is his most prized possession. He’d never let it out of his sight!”

Wendy with the prized shovel

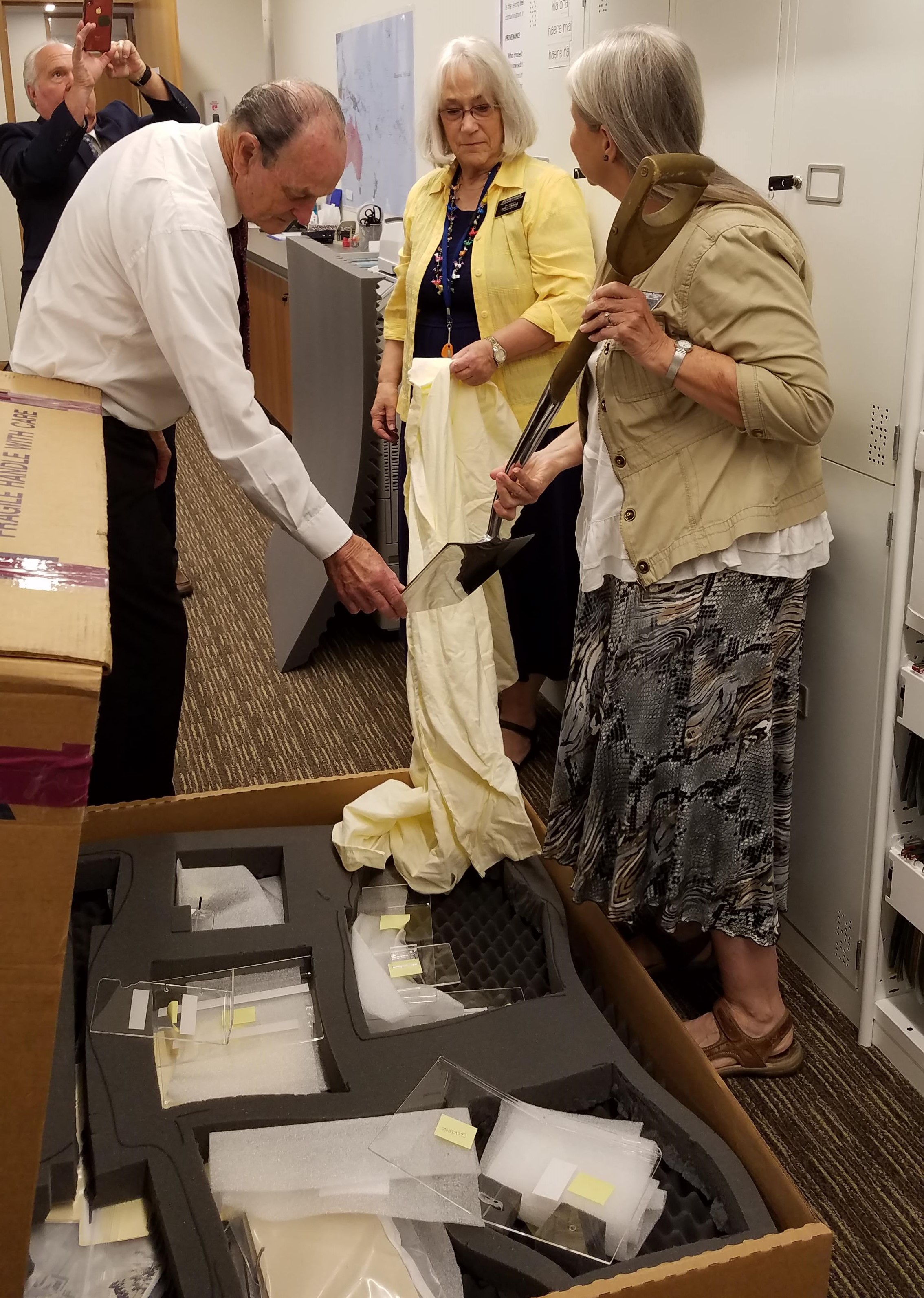

Wendy was thus reluctant to even ask her brother to consider sending the shovel to New Zealand, but agreed to request the loan on behalf of the Pacific Church History Museum. We all prayed for her as she worked up the courage to call, praying also that Davido would consent. To everyone’s surprise (O we of little faith!) he did! Within the next few weeks, he had delivered the shovel (its blade chrome-plated and engraved with the date of the groundbreaking) to the Church History Department in Salt Lake City, where eventually it was carefully packaged and shipped to us, along with facsimiles of other New Zealand Temple-related artifacts stored in Salt Lake’s Church History Archive that were too fragile to ship.

Vic, Diane, and Wendy unpack the shipment of artifacts, while Alan documents the moment

The box we received also contained acrylic mounts for all the artifacts we planned to display, custom-made by a collections care specialist at the Church History Museum. In order for Scott to create them, Catherine and Diane, our own collections care specialists, had to send precise measurements and photographs from multiple angles for each item. Wayne also used those measurements and photos to design a layout for each display case. The cases themselves would be manufactured here in New Zealand by the same professional firm that had built and installed all the existing displays at the MCPCHC.

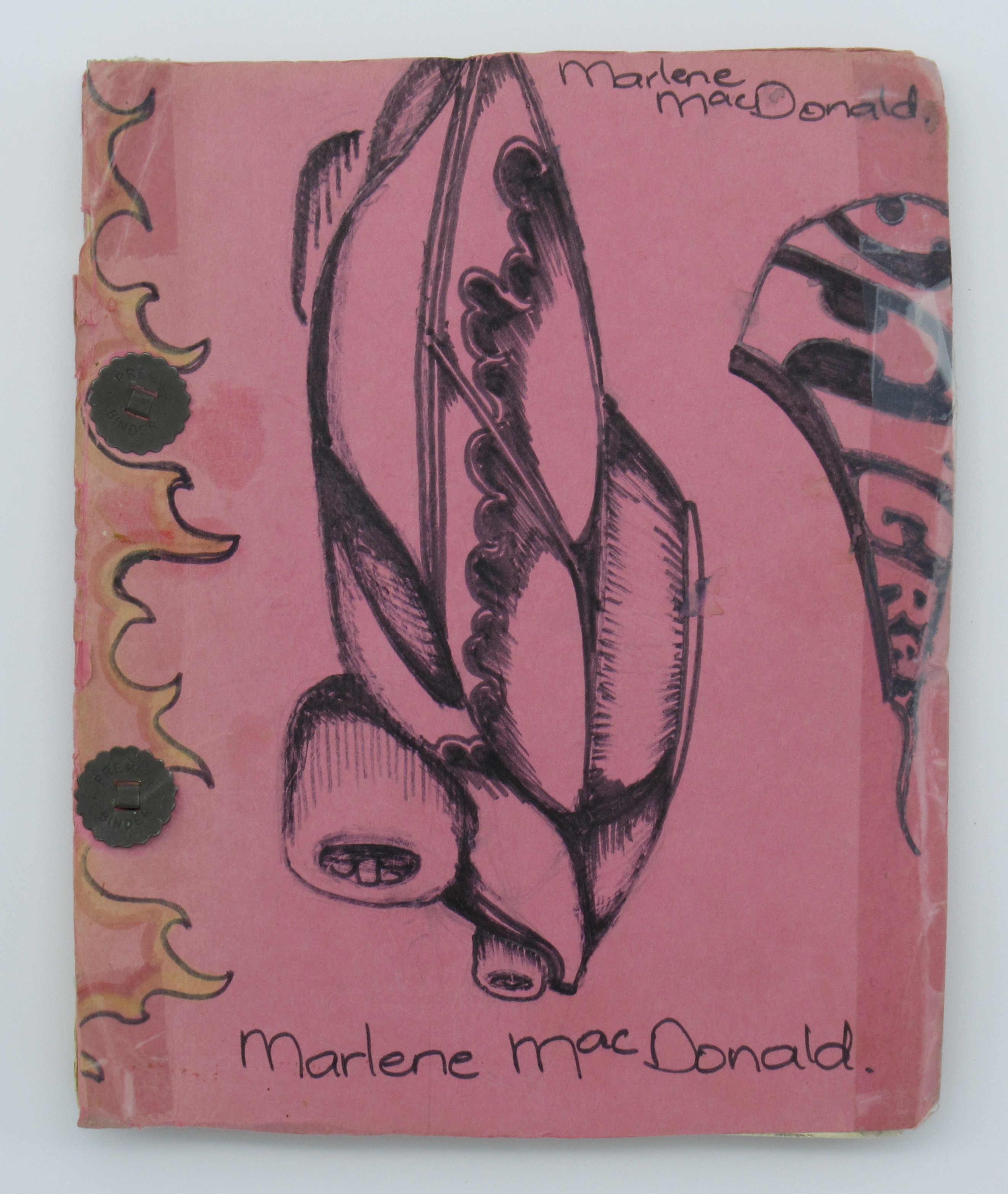

The 1957 cookbook with an anachronistic “Sting Ray” cover wasn’t exactly what we wanted to display

Most of the historic artifacts to be included in the Sacrifice and Consecration exhibit would come from the MCPCHC archive, but Barry and Eva also reached out to Hoki, chair of the New Zealand Labour Missionary Association, to ask if she would solicit artifact donations or loans from its members. Through her, we were able to obtain more interesting objects from The Project era. The item that most captured Nancy’s attention was a copy of the College Branch Relief Society Cookbook, compiled in 1957 as the culmination of a two-year nutrition course the women had undertaken. It offered a fascinating glimpse into daily life for families living at the construction camp—as well as some charming vintage recipes. Unfortunately, the copy that had been lent to us was unsuitable for display because its original cover had been replaced with pieces of posterboard on which someone had drawn a picture of a Corvette Sting Ray (circa 1969), and the rusty brad fasteners with which the pages were held together would not allow them to lie flat when the book was open, making it difficult to digitally scan them for a facsimile. Eva circulated a request among the families of former labor missionaries living in Hamilton for another copy of the cookbook, hoping to find one with the original cover intact, but to no avail.

Wendy, however, came through for us once again. Her older sister, living in Utah, still had the copy of the 1957 cookbook that had belonged to their mother. Sadly, its cover was missing, too, but the pages were contained in a looseleaf binder that made scanning much more convenient. Moana lent the cookbook to the Church History Department in Salt Lake City for digitization, and then Tyler, another collection care specialist, created a nifty facsimile for us to display, complete with a few food stains on the open pages. Nancy chose three representative recipes to include in a booklet about how the labor missionaries were physically and spiritually nourished, which museum visitors would be able to take with them as a memento of the exhibit.

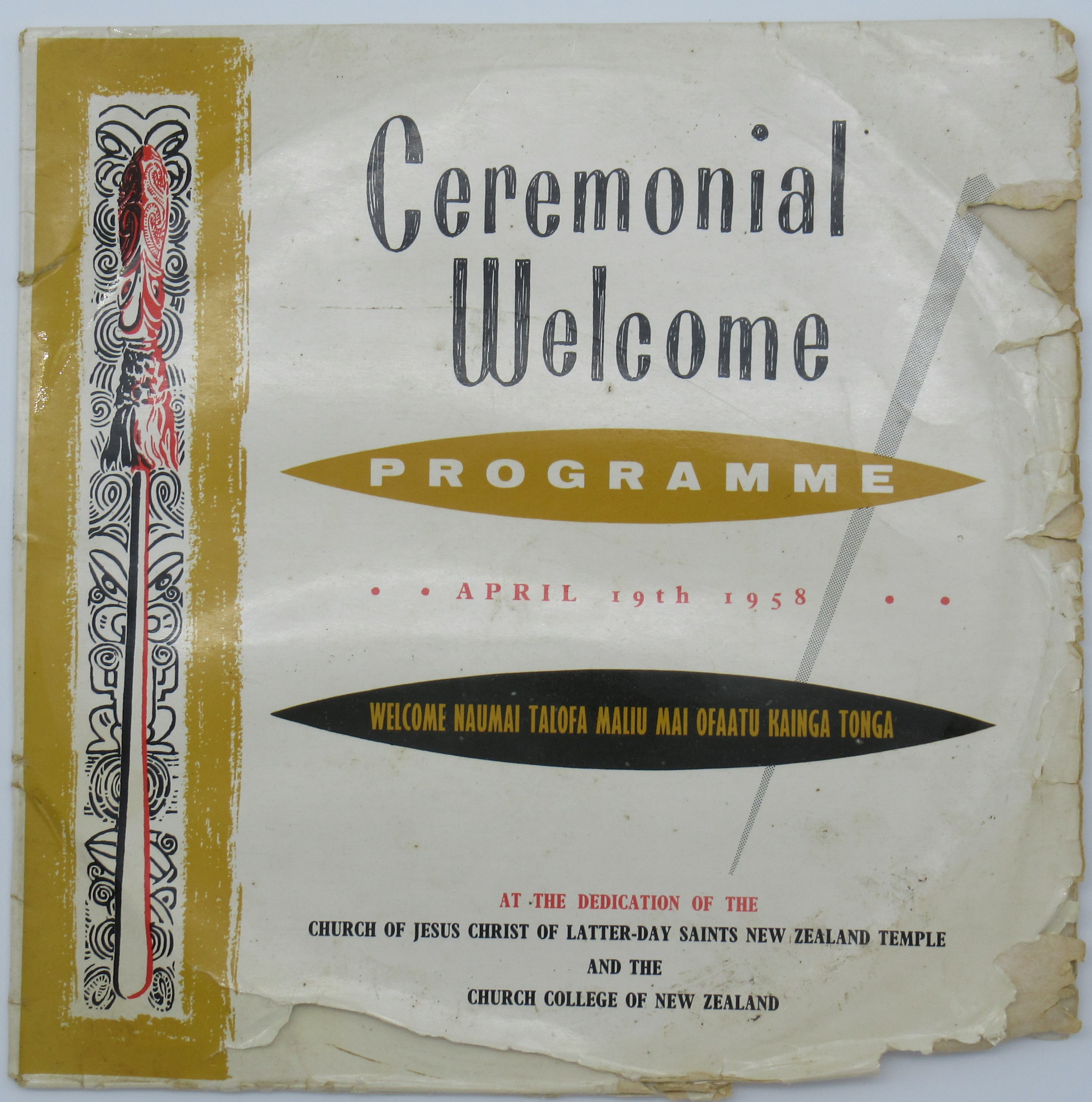

The cover of the 1958 vinyl LP recording

As we reviewed Wayne’s layout for the artifacts to be displayed in the smart-glass case, we admitted that it wasn’t very exciting—not through any fault of Wayne’s, but because the items were mostly flat, rectangular documents: programs from the temple dedication and the Ceremonial Welcome event that preceded it, and books of architectural and interior design specifications for the temple. They weren’t very engaging if you couldn’t look inside and turn the pages. We were lamenting this fact during a virtual Museum Team meeting when Michael said, “You know, all those items have been digitized. Couldn’t we provide a screen next to the display case where visitors could scroll through the image files and look at the pages?” Of course we could. A kiosk for the oral history video clips had already been designed; we just needed to get funding approval to build and program another kiosk. That wasn’t hard.

Māori dancers at the Ceremonial Welcome

Another feature added to the second kiosk was a selection of audio clips from the original vinyl LP recording of the Ceremonial Welcome, a four-hour gala that took place the day before the temple dedication. It included a full Māori pōwhiri (welcome ceremony), speeches by President McKay and other Church leaders, and a few dozen musical performances. Michael spent several days listening to the whole recording so he could choose the best 30-second sound bites to give listeners a representative taste of the songs and dances performed by groups from New Zealand, Samoa, and Tonga.

Audio-Visual Components and Images

The COVID clouds that descended on the whole world while the Sacrifice and Consecration exhibit was in development had at least two silver linings for us. The first was that during the two months of 2020 when the Matthew Cowley Pacific Church History Centre was closed, Eva and Nancy did not have to worry about operating the museum or greeting visitors to the Reading Room, and thus had more time to prepare for the exhibit. The Church History Museum and its offices in Salt Lake City closed, too—as it turned out, for much longer than their New Zealand counterparts—so Tiffany and her colleagues at headquarters also had more time to devote to the MCPCHC’s new exhibit. The pandemic’s second silver lining was more available cash. Because the Church History Department had put virtually every worldwide project except ours on indefinite hold, and because CHD employees were not using any of its travel budget, we became the beneficiaries of previously allocated money that others were unable to spend.

A more generous budget did more than buy us a second kiosk; it also allowed us to expand the number of videos we could include in the exhibit. Rangi, Vic, and others had recorded hundreds of hours of interviews with former labor missionaries for Church History archives. From that trove, Eva and Barry culled about 35 of the most compelling interviews, and then selected the best few minutes from each to advance the key messages of the exhibit. Because the videos in the archive had been made over a period of thirty years with whatever recording equipment had been available at the time, their quality varied wildly, so we planned to turn the footage over to the Church’s Film and Video Department to clean up. The initial budget for the exhibit allowed for only 15 to 20 video clips to be professionally enhanced, so we were afraid we’d have to eliminate about half the interview segments that had been chosen, but thanks to COVID we were given a green light for the Film and Video team to refurbish all of them.

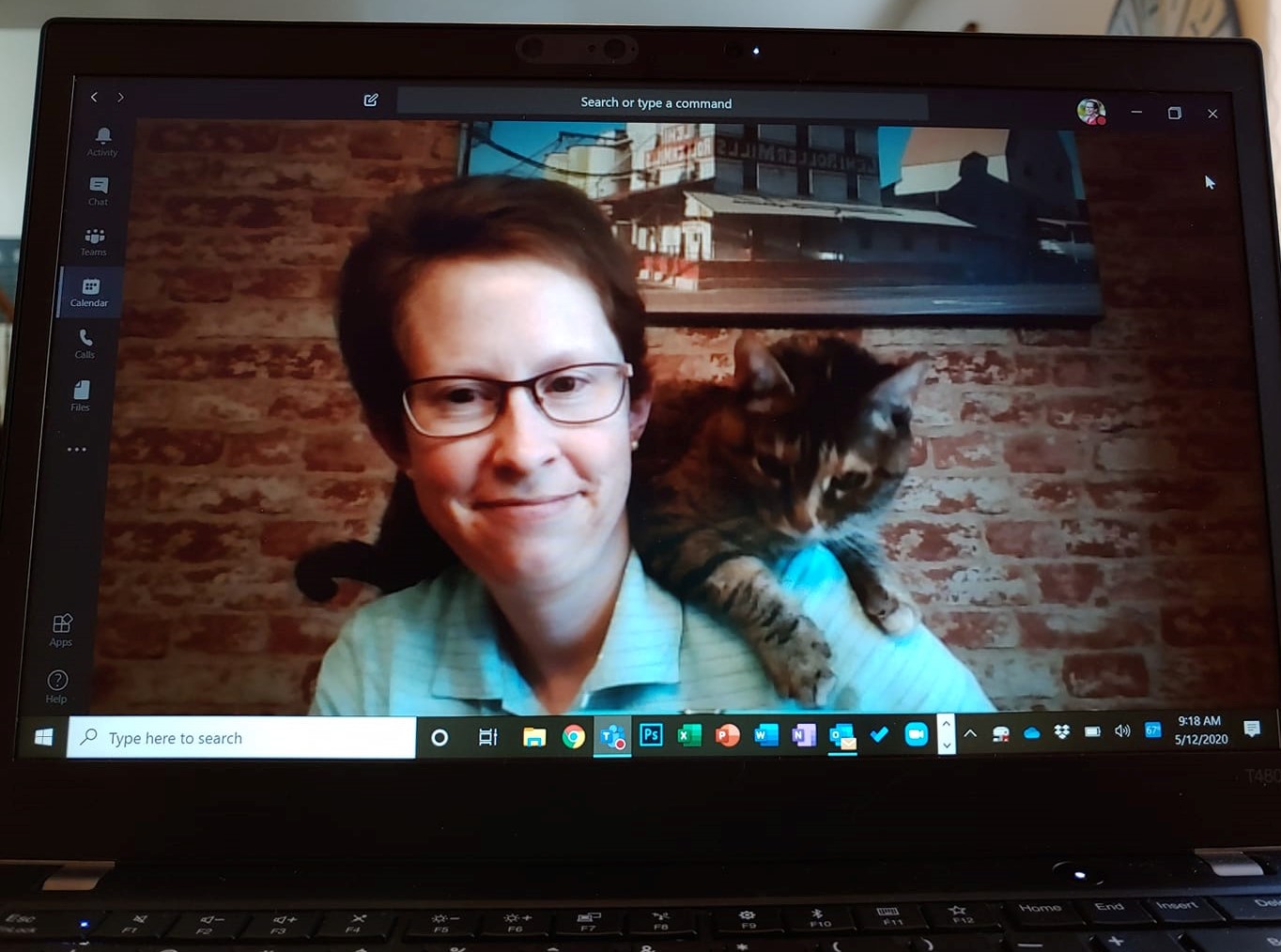

Tiffany and Tiger Lily in a virtual team meeting during lockdown

Meeting virtually with Tiffany and Quinn, the senior producer assigned to our project, Eva and Nancy described the objectives of the Sacrifice and Consecration exhibit and explained what we wanted the Film and Video team to do with our clips. We didn’t expect anything fancy; we just hoped they could edit out the speakers’ hemming and hawing, make fuzzy footage a little clearer, and eliminate distracting background noise. We also wanted them to add introductory slates to identify each speaker, and to give the video segments a consistent, professional look. Quinn immediately understood what Eva and Nancy hoped to achieve in terms of production values, but admitted that he knew little about the history of the Church in New Zealand. He asked Eva to send the digital video files, along with the timestamps she and Barry had noted for the segments they wanted to use, so he could estimate how much work the project would require and begin thinking about how to format the video clips to coordinate with the museum exhibit.

When the three women met with Quinn again the following week, his first comments were something along the lines of: “I watched all your videos and was blown away. You’ve got some very compelling interviews! It’s obvious that the labor mission experience was pivotal in the lives of these people, and their stories are so moving—I was in tears!” He went on to say that he’d heard of the Church College of New Zealand, but I had no idea that it—and the temple—were built by volunteers, and asked us to recommend something he could read to get more background on the history. Eva gave him a few suggestions.

The next time Tiffany, Eva, and Nancy talked with him, Quinn had done his reading. He exclaimed, “This is a story that needs to be told! I can’t believe the Church hasn’t already made a movie of it, because it’s so cinematic! I checked, and I can’t find anything in the film archives on New Zealand’s labor missionaries. I know you want to keep all your videos for the exhibit short because visitors will be looking at them on a kiosk, but what would you think about having us put some of them together in a longer film with more of a narrative? You have a theatre at the museum, right? So we could make a 45-60-minute documentary film that would use some of the interviews but tell more of the story. Would you be interested in something like that?”

In our earliest discussions about the Sacrifice and Consecration exhibit, we had considered requesting that the Church produce a film about New Zealand’s labor missionary program, but discarded the idea as too much to ask. Now a senior producer from the Church’s Film and Video Department was asking if we would be interested in a 45-60-minute documentary to go along with our exhibit. Of course we were interested—but we weren’t sure we could get funding for such a project. Quinn was so enthusiastic about the idea of a longer film, however, that he offered to put together his own proposal for funding from the Film and Video budget instead of the History Department budget. After all, many of F&V’s production projects had been suspended due to COVID restrictions, and with no live-action shooting and no traveling taking place, the F&V staff had little to keep them busy. A documentary that could be assembled from existing footage in the Church archives could fill a lot of their otherwise idle hours, so it seemed a win-win for everyone. We told Quinn to go for it, and a budget for a new film was soon approved.

Quinn drafted a narrative script for the film and then asked Nancy to review it for historical accuracy and offer editing suggestions. As they worked together to revise the script over the next several weeks, Nancy delved into Church History archives to verify information Quinn wanted to include and answer questions that came up. When the time came to start adding visual components to the narration, Quinn sent Tiffany and Nancy a list of the types of images he had in mind, so Tiffany took charge of searching the Church History Catalog while Nancy checked the New Zealand National Library and dug deeper into Rangi’s “sandbox,” the bottomless pit of digital files where the treasures Rangi had collected were buried. Sadly, Eva had been released as associate director of the MCPCHC by this time, so only two of “The Three Musketeers” who had worked so closely together for so many months were able to carry on. (Michael assumed Eva’s place on the video advisory team and contributed to the image search, but with a guy in the room, Three Musketeers meetings just weren’t the same as they had been with Eva.)

Māori Church leaders Hohepa Heperi and Stuart Meha delivered kōrero (speeches) at the Ceremonial Welcome

President David O. McKay invited people from all the Pacific islands to become one in Christ

Before Eva’s term at the MCPCHC was over, however, she had initiated yet another video project. After the decision was made to include audio clips from the Cultural Celebration on the second kiosk, Eva began gathering still images of the event for museum visitors to look at as they listened. In the process, she discovered some vintage 8mm films taken by people who had attended the 1958 extravaganza. There wasn’t a lot of footage, but she hoped the F&V production team could use it to enhance the visitor experience at the kiosk. The result was even better than expected. As Eva and Michael identified exactly which performances had been captured on film, F&V’s editors used their technical wizardry to coordinate the visuals with corresponding audio from the vinyl LPs, producing a ten-minute video that encapsulated the excitement of the Ceremonial Welcome and made it come alive. The day the file for the first cut of this video arrived in Eva’s inbox, she took a look and then called everyone to gather around her desk so all of us could experience the magic of hearing Hohepa Heperi, one of the Church’s first Māori high priests, deliver a florid welcoming kōrero while his image appeared on the screen. Listening to David O. McKay, the snowy-haired prophet of our childhood, address Church members from all over the Pacific was thrilling, and it was amazing to watch hundreds of costumed dancers move in synch with music that had been recorded on a completely separate track. This splendid Ceremonial Welcome video would now join the lineup being prepared for viewing in the theatre, which included some longer (5-10-minute) clips from labor missionary interviews and a photomontage of the construction of the temple (set to inspiring music), as well as Quinn’s documentary.

When we began trying to look at what we were creating for the Sacrifice and Consecration exhibit through the eyes of a typical museum visitor, we realized that we were providing too much to absorb in a single visit. This was especially true of the videos. No matter how engaging the labor missionary interview clips might be, offering visitors a choice of 38 2-minute videos to watch while they stood at the kiosk seemed too much. To avoid overwhelming our guests, we asked the programming team to load all 38 interview clips into the kiosk but limit the selection to only 15 at a time. The options would change every day on a rotating, randomized basis, so visitors could see something new every time they came back. Anticipating that some visitors might be disappointed if the video of Aunty Lil or Papa Ra that their cousins had told them about did not appear on the kiosk menu for that day, we asked the F&V team to produce a complete set of the short videos that were formatted for projection on a big screen so we could show them in the theatre on request.

Kara’s father captured memorable images of his crew

In addition to choosing appropriate still images to cover edits and break the monotony of talking heads in the interview videos, we also had to select pictures for the wall displays to illustrate stories and reinforce our key messages. With thousands of photos to choose from there was no excuse for not finding the perfect image for each situation, but given the disorderly state of our files, finding the perfect image remained a challenge. Our task was made somewhat easier after our long-time friends Kara and Jeff agreed to digitize hundreds of the photos Kara’s father had taken while he was serving as head of The Project’s plumbing crew. These were high-quality color images, and many of them turned out to be exactly what we were looking for in terms of subject matter.

One of Wayne’s most brilliant design decisions was to fill one entire wall of the exhibit space with a near-life-size enlargement of a photograph taken outside the partially completed temple on the day in December 1956 when the cornerstone was laid. The image includes more than two hundred individuals—labor missionary families and honored guests—and has become the most popular feature of the exhibit. It’s irresistible to stop and try to identify people, or simply gaze into their faces and imagine how they must have felt as they gathered in front of the House of the Lord, a house they were building themselves.

Editing and Approvals

As we noted earlier, one of the major challenges of developing the Sacrifice and Consecration exhibit was deciding what to leave out. Keeping the focus on the temple, the Saints’ willingness to sacrifice, and the key messages of each section aided the process of elimination, but even stories that made the final round had to be trimmed to the bone to avoid overcrowding the wall displays and overwhelming visitors with too much text. Tiffany edited with the skill of a plastic surgeon, excising nonessential words and phrases from the body of Nancy’s work so delicately that Nancy hardly felt any pain. Nevertheless, the editor from the Church’s Publishing Services Department pointed out a few necessary amendments that both Nancy and Tiffany had overlooked. One such instance provoked giggles: In a story about a Tongan family’s struggle to raise the money they needed to travel to the temple, Nancy had written that the father “stripped and sold the siding off their house” without considering that the mental images that phrase evoked might include an inappropriate one. “Stripped” was changed to the less picturesque but less problematic “removed.”

More painful than editing was the process of documenting each bit of historical information and ensuring that the Church History Department had the legal right to share every story, image, quotation, and recording we planned to use in the exhibit. Establishing legal rights was tricky because so much of our material had come from the Kia Ngawari Trust Collection, the mass of documents, photographs, and artifacts that had been given to Rangi and Vic over the years. The items had been offered freely, and because Rangi and Vic had never considered the need to collect signatures granting permission for the items to be shared, few KNT items have corresponding donor agreement forms. When the Church’s intellectual property lawyers began asking Tiffany for evidence of our rights to publicly display what we had chosen to include in the exhibit, and Tiffany began asking us where to find the applicable donor agreements, we had to confess that in the case of most items from the KNT Collection, such documents didn’t exist. For a while it appeared that this legal issue could derail the whole exhibit, but trying to track down individual donors at this point was an impossible task that none of us Church History missionaries had the energy to take on. “This is above your pay grade,” Tiffany agreed. “I’ll see what I can do to explain the situation to IP. Maybe once they understand that the KNT Collection was donated en masse to the Church History Department, and that KNT trustees did sign a donation agreement for the whole collection, they’ll accept that as sufficient evidence of permission for individual items to go on public display.” For several anxious weeks, we waited to hear the legal department’s verdict after Tiffany pleaded our case, and the workroom of the MCPCHC erupted in cheers when she finally announced that the judges had ruled in our favor.

Scheduling

The Hamilton New Zealand Temple as it looked in early 2020

The original plan called for the Sacrifice and Consecration exhibit to be installed by the time the renovated Hamilton New Zealand Temple was ready to reopen. When the temple closed in June 2018, it was announced that remodeling would take about three years, so everyone expected that the open house would occur in June 2021. With that in mind, we initially set a goal to open our exhibit in May, but then we heard rumors that the temple renovation was ahead of schedule and it was possible that the building would be ready to reopen much sooner.

During the open house in 1958, more than 112,500 people toured the edifice

During the three weeks the temple was open to the public before its dedication in April 1958, over 112,500 visitors lined up to tour the building—about three times the population of Hamilton at the time—and we anticipated that at least that many Church members and curious non-Latter-day Saints would come to the open house this time around, too. We hoped that a significant fraction of visitors also would come to the Matthew Cowley Pacific Church History Centre, and we didn’t want any of them to miss the opportunity to learn about the temple’s unique construction history. So we decided to shoot for opening the exhibit by the end of March 2021.

Then COVID threw everyone’s schedules out of whack. Construction workers in New Zealand were furloughed during the Level 4 lockdown, and even when they were allowed back on the job after the country shifted to Level 3, border closures wreaked havoc with the import of building materials. We heard rumors that it might be December 2021 before the temple renovation was complete, but we stuck to our plan to open the exhibit at the end of March.

It was a sad day when Elder and Sister G were released as directors of the MCPCHC in mid-January 2021, but not as sad as it might have been. Unwilling to leave New Zealand, where COVID had been effectively contained, and return to the U.S., where the disease was still raging unchecked, Barry and Eva had applied for and received another New Zealand mission call. They would not be able to oversee the final months of preparation for the museum exhibit, but at least they would be able to come down from their new assignment in Auckland to see the fruits of their labors when the exhibit opened.

Hori and Jo-Ena E. became directors of MCPCHC in January 2021

Elder and Sister E, the MCPCHC’s new directors, brought a completely different mindset to the Sacrifice and Consecration project that they had inherited. Not only native Kiwi but also ethnic Māori, Hori and Jo-Ena ensured that we didn’t perpetrate any cultural faux pas (such as obscuring part of someone’s head with another design element in a photograph) and offered a vision for the opening reception distinct from anything we Americans might have planned. Both Hori and Jo-Ena have close relatives who had been labor missionaries, so they were especially sensitive to how the exhibit would be perceived by others with similar connections.

While Elder and Sister E focused their efforts on planning a gala exhibit opening that would appropriately honor the labor missionaries and their legacy, those of us who had been involved with exhibit preparation from the beginning bore down on the finishing details. As the end of March approached, we realized that there was still much to do. The video segments for the kiosk had been edited but had not yet been technically enhanced, and that had to be done before the digital files could be compressed and sent to programmers for installation on the kiosk. The kiosks themselves had not been fabricated, nor had the display cases. Besides, at this point the entire MCPCHC staff was also preparing for a full weekend on duty at Hui Tau 2021, so it seemed prudent to postpone the opening until mid-April.

Just before Hui Tau, we learned that because of a delay in the shipment of a sheet of smart glass from the U.S. to New Zealand and subsequent problems getting the glass through customs, the display cases for the exhibit would not be ready until the first week of May. The opening was postponed again.

This was not such a bad thing because Hori and Jo-Ena had been encountering difficulty obtaining addresses for the former labor missionaries they hoped to invite to the opening reception. Indeed, they had difficulty even assembling an accurate list of the labor missionaries who were still alive. We laughed ruefully when Hori told us about a phone conversation he had with one former labor missionary.

“Have you contacted Brian H_____ yet?” the man asked.

“No,” said Elder E. “According to the list I got from the Labour Missionary Association, Brian is deceased.”

“Well, he wasn’t deceased when I talked with him on the phone last week,” the man replied. “He’s in a nursing home in Hastings. Here’s his number.”

Creating a mailing list was only one of the challenges Hori and Jo-Ena faced regarding invitations. Because the opening reception was to be sponsored by an official Church organization, the wording for the formal invitation had to be edited by the Publishing Services Department and the whole design approved by ecclesiastical authorities before the cards could be printed—a process that would add at least a week of lead time before we could get the invitations in the mail. But an even more fundamental problem was that the when and where of the opening event kept changing. The when depended not only on how soon exhibit components would be ready for installation, but also on when professional installers would be available to do the job. Complicating matters was that a member of the Church’s Pacific Area presidency was to preside over the proceedings, so we had to ensure that our event did not conflict with anything on his calendar. Eventually we settled on Saturday 22 May as Opening Day, and to accommodate the needs of our elderly guests, the reception would be scheduled for the afternoon. The where, however, was still in question.

It would seem natural for the exhibit opening to take place in the museum gallery, with a short program in the adjacent theatre, but the number of potential guests exceeded the theatre’s 70-seat capacity. Moreover, the theatre has no provisions for patrons with limited mobility: no designated spaces for wheelchairs, no ramps, and no handrails to help aged labor missionaries negotiate the steps. It’s a shocking situation that we’d been discussing with the facilities manager for months because it violates New Zealand’s safety codes, but no remedies were likely to be implemented in time for the opening. We considered moving the program to the Kai Hall, the historic dining hall built at the construction camp for the labor missionaries and later used by boarding students at CCNZ; an advantage it offered was that we could serve food there, which we couldn’t at the MCPCHC unless we could somehow squeeze upwards of 100 guests into our 25-seat staff lunchroom. The main disadvantage of the Kai Hall was that it’s located about 300 metres from the Mendenhall Building where the MCPCHC is located, so we’d have to shuttle infirm guests between the two buildings, but it still seemed to be our best option. However, when Sister E tried to book the Kai Hall for 22 May, she learned that both it and the nearby David O. McKay Stake and Cultural Event Centre were already reserved for a multi-stake Young Single Adult conference. Ayayay! Now we were going to have to compete with hundreds of YSAs not only for a venue but also for parking space on the Temple View campus. Another potential headache associated with the YSA conference was that although the museum would be closed to the public during the exhibit opening, the Church Distribution Centre on the ground floor would still be open and probably would draw a lot of those exuberant (read: loud) young visitors into the building. Nevertheless, as 22 May drew nearer, we realized that we really had no choice but to hold the opening gala in the MCPCHC’s gallery, theatre, and lunchroom—and pray that somehow everything would work out. The invitations were printed and put in the mail about ten days before the event. About half of the surviving labor missionaries still live in Temple View, so Ken, one of our most loyal Church History volunteers, offered to hand-deliver their invitations.

Installation

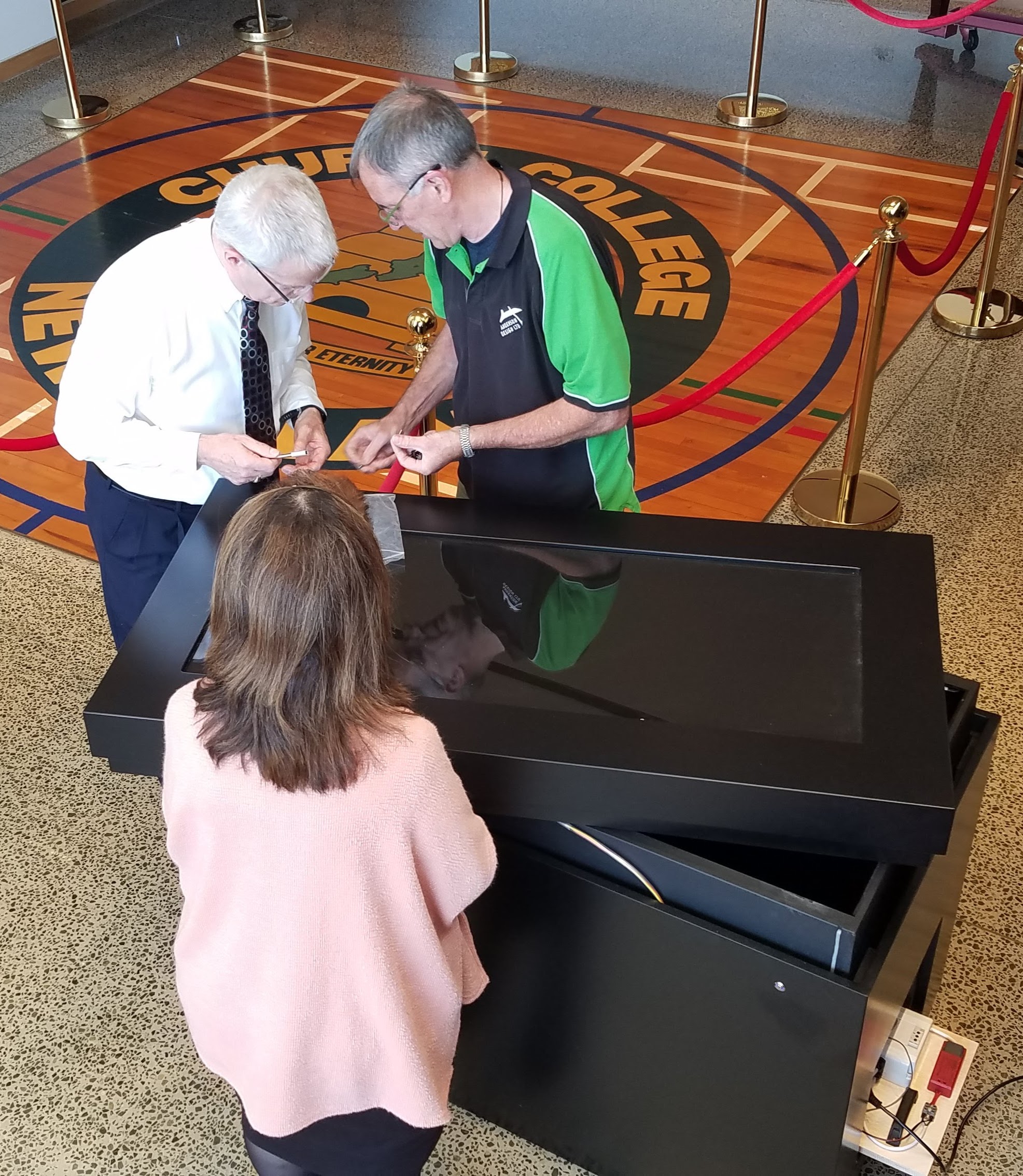

Ian, whose company built the display cases, shows Michael and Jo-Ena how to assemble and operate the smart glass case

Physical preparations for the exhibit’s installation had been taking place for several weeks. Electricians had installed additional outlets along the gallery walls to supply power to the kiosks and the smart glass display case. The Light and Life photography display was taken down, and the W-shaped wall on which many of the pictures had been mounted was removed. It would be replaced by a similar wall, but the new one would be modular so that it could be reconfigured in various ways for future exhibits. The display cases arrived and were put into a makeshift storage area under the main staircase until it was time to move them up to the gallery.

Michael, Nancy, and our advisers at the Church History Museum in Salt Lake City expected the Sacrifice and Consecration exhibit to be installed over the weekend before the opening. We might try to cordon off part of the gallery, but we weren’t too worried about allowing that week’s museum visitors to get a preview. Elder and Sister E, however, had different ideas. Ceremonial hura (unveilings) are an important part of Māori culture, held when a memorial marker such as a gravestone is placed, or even when a new product is brought out (as we had seen at the book launch during Hui Tau 2021). Hori and Jo-Ena felt that because this exhibit honored the sacred sacrifices of the labor missionaries it deserved a formal hura, so as much of the installation as possible was put off until the night before the opening, and arrangements were made to cover whatever elements could be covered until the unveiling ceremony on 22 May.

An installer cleans up after the fallen wall panel was replaced

When we arrived at work on Friday 14 May, a week before Opening Day, we saw that the huge display panels that would cover the gallery’s 4-metre side walls had been installed during the night. The Mendenhall Building’s facilities manager had nixed the wallpaper-type vinyl wall coverings that our Salt Lake advisers had described to us in favor of the vinyl-covered aluminum panels that our local fabricator preferred, because supposedly the adhesive used for the latter would result in less damage to the existing wall surfaces. What we saw that Friday morning didn’t inspire much confidence in the wisdom of that decision, however, because one of the heavy aluminum sheets had already slipped from the wall and was lying on the gallery floor.

When the adhesive failed, the aluminum panels had to be bolted to the wall

“What if that had fallen on a visitor?!” Jo-Ena exclaimed, horrified. The installation crew was brought back immediately to bolt the panels to the wall.

Admitting the impracticality of trying to veil the gallery walls, Jo-Ena had decided to simply drape a decorative red ribbon across the displays, which then could be ceremonially cut during the hura. The twenty or so museum visitors who came during that week thus got a sneak preview of the exhibit’s shell, but it was our volunteer docents who were most enthralled. Even though we had been telling them about the new show for months and trying to describe how it would look, the real-life experience was captivating—especially that giant image of the labor-missionary group at the cornerstone-laying.

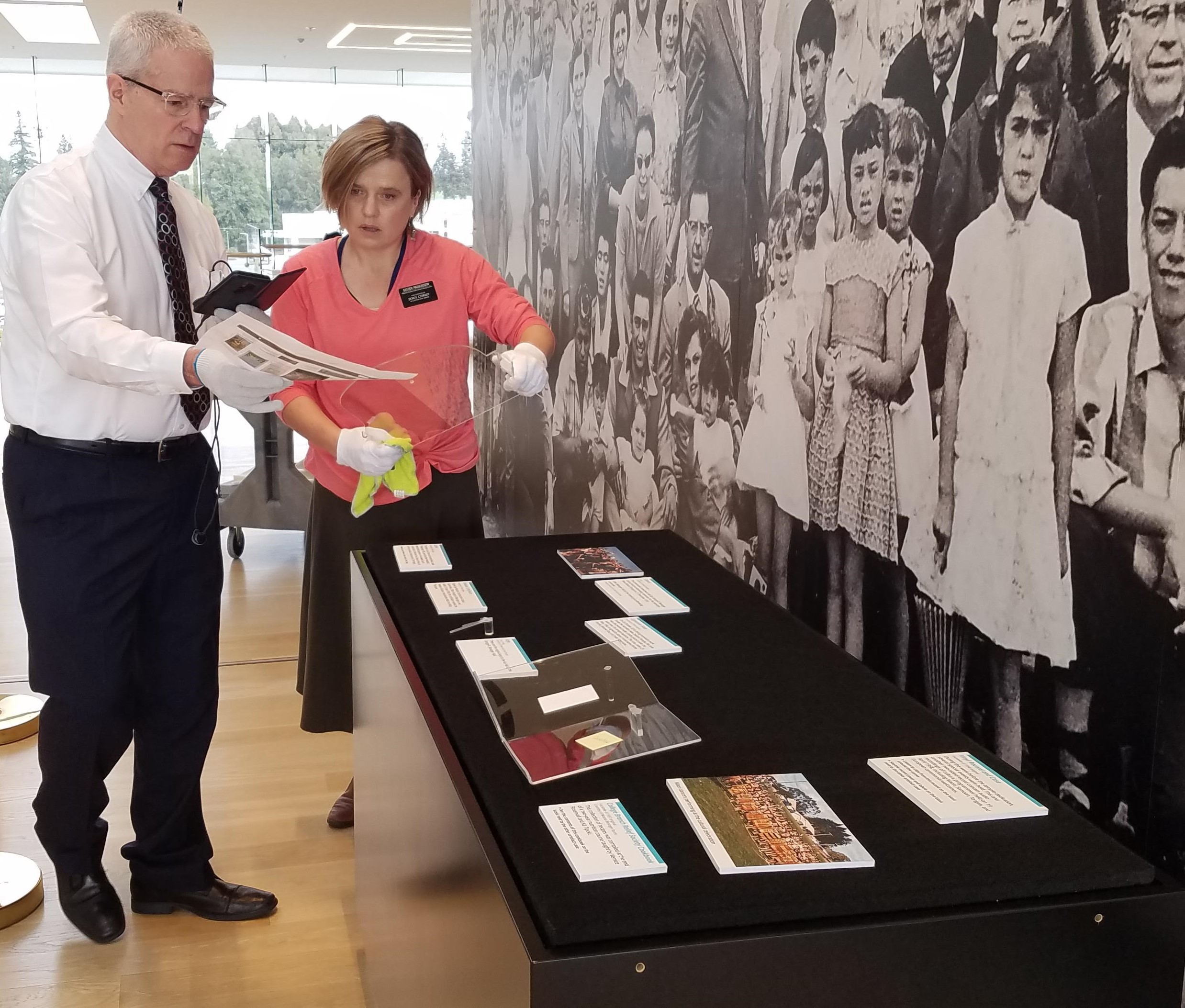

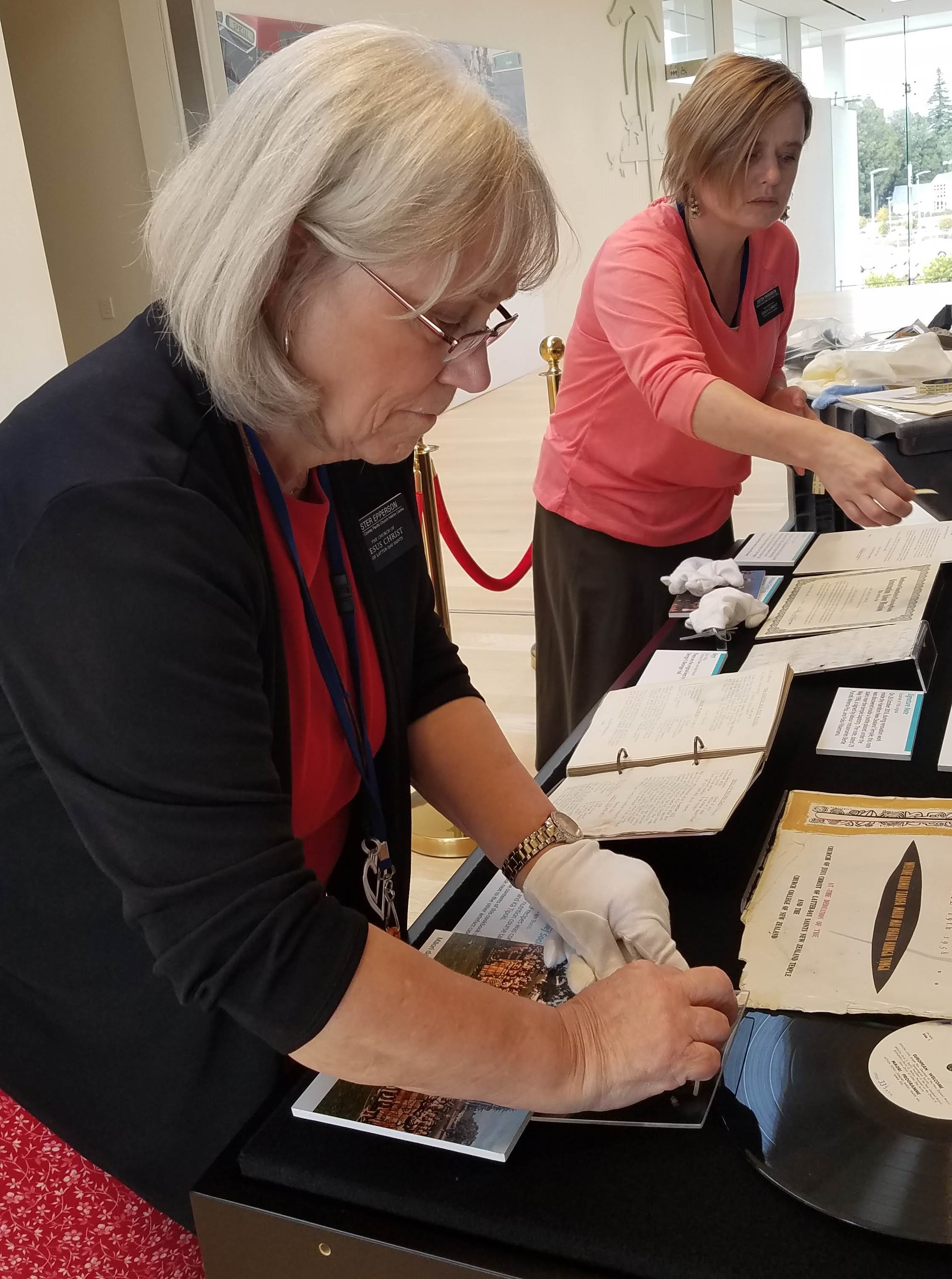

Michael and Catherine arrange mounts and labels for the artifacts in the display case

Diane and Catherine position the artifacts in the case

Two days before the opening, the display cases were moved into position upstairs and thoroughly cleaned so they could be filled with the selected artifacts. Following Scott’s real-time virtual instructions as well as Wayne’s layout designs, Catherine, Diane, and Michael carefully unwrapped each object and positioned it on its custom mount while Nancy finished cleaning the Plexiglas bonnet for the conventional case. After the label for each item had been set in place and all stray motes of dust had been whisked away from the black velvet display surfaces, the transparent lids were secured to the bases and the cases were covered with the black drapes Diane had prepared to keep the artifacts hidden until the official opening.

Installation of the exhibit’s remaining physical components—the modular walls and the kiosks—was slated for 7 p.m. on Friday 21 May, less than 18 hours before we expected our guests to begin arriving.

(to be continued)

If the documentary about the labor missionaries is as riveting a narrative as is this preparation for Sacrifice and Consecration, please tell me it’s available to watch somewhere!

Thank you so much for sharing your experience in prepare this exhit but also the stories of the labor missionaries. It really touched my heart when it was said if the labor didn’t show up to work they didn’t get paid. Because they were serving the Lord as labor missionaries they performed to their best.

Thanks for sharing!