As Memorial Day 2020 approached, we wondered how the Montgomery Ward of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints could possibly proceed with its annual Memorial Day picnic in the Time of COVID-19. This event had already been established as the ward’s premier social by the time we moved to Cincinnati in 1996: a day when the great cooks of Montgomery would supplement the obligatory grilled hamburgers and hot dogs with their best recipes for tossed green salad, potato salad, pasta salad, cabbage salad, bean salad, spinach salad, taco salad, quinoa-and-avocado salad, fruit salad, baked beans, macaroni and cheese, et cetera, et cetera, et cetera (and we haven’t even begun to list the desserts), and when current ward members, former ward members, future ward members, relatives of ward members, and friends of ward members would come together to eat and play and talk—no matter how uncomfortable the weather. Over the years, we had to keep changing the venue as increasing attendance kept overwhelming one park shelter after another, even when we trucked more banquet tables over from the church.

As Memorial Day 2020 approached, we wondered how the Montgomery Ward of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints could possibly proceed with its annual Memorial Day picnic in the Time of COVID-19. This event had already been established as the ward’s premier social by the time we moved to Cincinnati in 1996: a day when the great cooks of Montgomery would supplement the obligatory grilled hamburgers and hot dogs with their best recipes for tossed green salad, potato salad, pasta salad, cabbage salad, bean salad, spinach salad, taco salad, quinoa-and-avocado salad, fruit salad, baked beans, macaroni and cheese, et cetera, et cetera, et cetera (and we haven’t even begun to list the desserts), and when current ward members, former ward members, future ward members, relatives of ward members, and friends of ward members would come together to eat and play and talk—no matter how uncomfortable the weather. Over the years, we had to keep changing the venue as increasing attendance kept overwhelming one park shelter after another, even when we trucked more banquet tables over from the church.

Montgomery Ward Memorial Day Picnic 2011

Montgomery Ward Memorial Day Picnic 2008

Montgomery Ward’s annual Memorial Day picnic may have appeared to center on food and socializing, but at its foundation was a desire to honor those who had given their all to protect the lives and liberty of others. We always appreciated the dignity with which the Boy Scouts conducted the flag ceremony, Mark McM’s resounding renditions of Amazing Grace on the bagpipes, the sweet, sorrowful tones of Taps emanating from Skyler’s bugle, and the inspirational stories shared by and about our servicemen and -women.

Until today, however, we had seen no online sign-up sheets, no pleas for extra grills, no announcements about the Memorial Day picnic on Montgomery Ward’s Facebook page at all. We’re in New Zealand and wouldn’t be able to attend, anyway, but we were saddened to think that the annual picnic would not be happening. Then we heard that the bishopric was planning to host an “Ice Cream Drive-Thru” in the church parking lot on the afternoon of Memorial Day. It won’t be quite the same, but at least the holiday won’t go by unobserved. We hope Skyler will play Taps as families pass by in their minivans, even if she has to put a mask over the mouth of her bugle.

New Zealand does not observe Memorial Day on the last Monday in May, nor even on 30 May, when it was commemorated in our youth; that’s an American tradition that began after the War Between the States. But New Zealand has its own holiday to remember and honor the sacrifices of its soldiers: ANZAC Day.

ANZAC Day, observed each year on 25 April no matter what day of the week the date falls on, commemorates the anniversary of the landing of the Australia and New Zealand Army Corps on Turkey’s Gallipoli Peninsula in 1915. The goal of the Allies’ Gallipoli campaign was to take control of the Dardenelles, the narrow passage between the Aegean and the Sea of Marmara, and from thence to take Constantinople. At the time, the area was controlled by the Ottoman Turks, who had entered the Great War on the side of Germany. France, Italy, Russia, and Britain—and the latter’s former colonies in the South Pacific—hoped that by capturing the Ottoman capital, they could knock the Turks out of the war. That goal proved elusive, and the campaign wore on for eight long months. Ottoman casualties were heavy, but the Turks held their ground. Allied troops finally gave up and left after losing more than 56,000 soldiers—8,709 of them from Australia and 2,721 from New Zealand. The number of Kiwi casualties may seem a small percentage of the total until you consider that 2,721 represents one-sixth of the whole New Zealand contingent in the campaign.

The ANZAC landing at Gallipoli, 25 April 1915

Both New Zealand and Australia began commemorating ANZAC Day on 25 April 1916, the first anniversary of the Gallipoli landing and only a few months after the Allied retreat. By then, both nations understood the extent of the campaign’s terrible toll and were bracing for more bad news from battlefronts on the other side of the globe. The worst came the next year from Belgium, where more than 5,000 members of the New Zealand Expeditionary Force were killed during a series of offensives near the town of Ypres. When the war finally ended in 1918, the Allies had triumphed, but more than 18,000 New Zealanders had been killed—over 15 percent of the country’s total population.

It’s easy to understand, then, why Kiwis were eager to establish an annual commemoration for their war dead. The anniversary of the start of the Gallipoli campaign, 25 April, persisted as the official day of remembrance because the ANZAC’s participation as part of the Allied forces marked a significant turning point for New Zealand as a nation. Even though they were fighting “for the crown” alongside other citizens of the Commonwealth, Kiwi soldiers really felt like they were representing New Zealand, not Great Britain, and thus the ANZAC became an important component of the Kiwi national identity. That sense of patriotic pride continues to be as much a part of ANZAC Day commemorations in New Zealand as the desire to honor the fallen.

We had learned that Kiwis observe this holiday with a great deal more solemnity than most Americans do Memorial Day, but unfortunately, Level 4 COVID-19 restrictions did not allow us to witness a traditional ANZAC Day commemoration this year. Sister T had told us about her moving experience a few years ago, gathering in the early-morning dark on ANZAC Day with at least a thousand Kiwis at a memorial park in Napier. Commemoration ceremonies traditionally begin at dawn because that is when the Gallipoli landing took place; participants “stand to” while a bugler plays The Last Post, the British Army’s equivalent of Taps. Ceremonies vary from place to place across New Zealand and Australia, but often include prayers, hymns, and poetry recitations in addition to wreath-laying and military parades. This year, all scheduled ANZAC Day gatherings were cancelled, but Kiwis were encouraged to rise before dawn, “stand to” at their front doors or next to their letterboxes, and listen to a live-streamed memorial service beginning at 6:00 a.m. The observance also included a performance of Abide With Me by a virtual brass band and choir comprising more than 130 musicians from all over New Zealand (and including several that we had met while we were participating in the Hamilton Civic Choir).

We began our own ANZAC Day observance a day early to avoid possible social-distancing issues in case other people had the same idea we did. On the afternoon of Friday 24 April, a gloriously sunny autumn day, we drove to Anzac Parade, a wide boulevard that crosses the Waikato River in central Hamilton. We parked around the corner on Memorial Drive and then walked along the east bank of the river to Soldiers Memorial Park, located at the point where British militiamen established Hamilton’s first pakeha settlement in 1864. The park features memorials to fallen soldiers from both world wars and other major conflicts. One of these is a garden acknowledging the shared grief between New Zealanders and the citizens of Ypres, Belgium, where so many soldiers of both nations gave their lives in 1916.

Monument in Soldiers Memorial Park

“Lest we forget”: memorial wall honors the dead from World War I

“Lest we forget”: memorial wall honors the dead from World War II

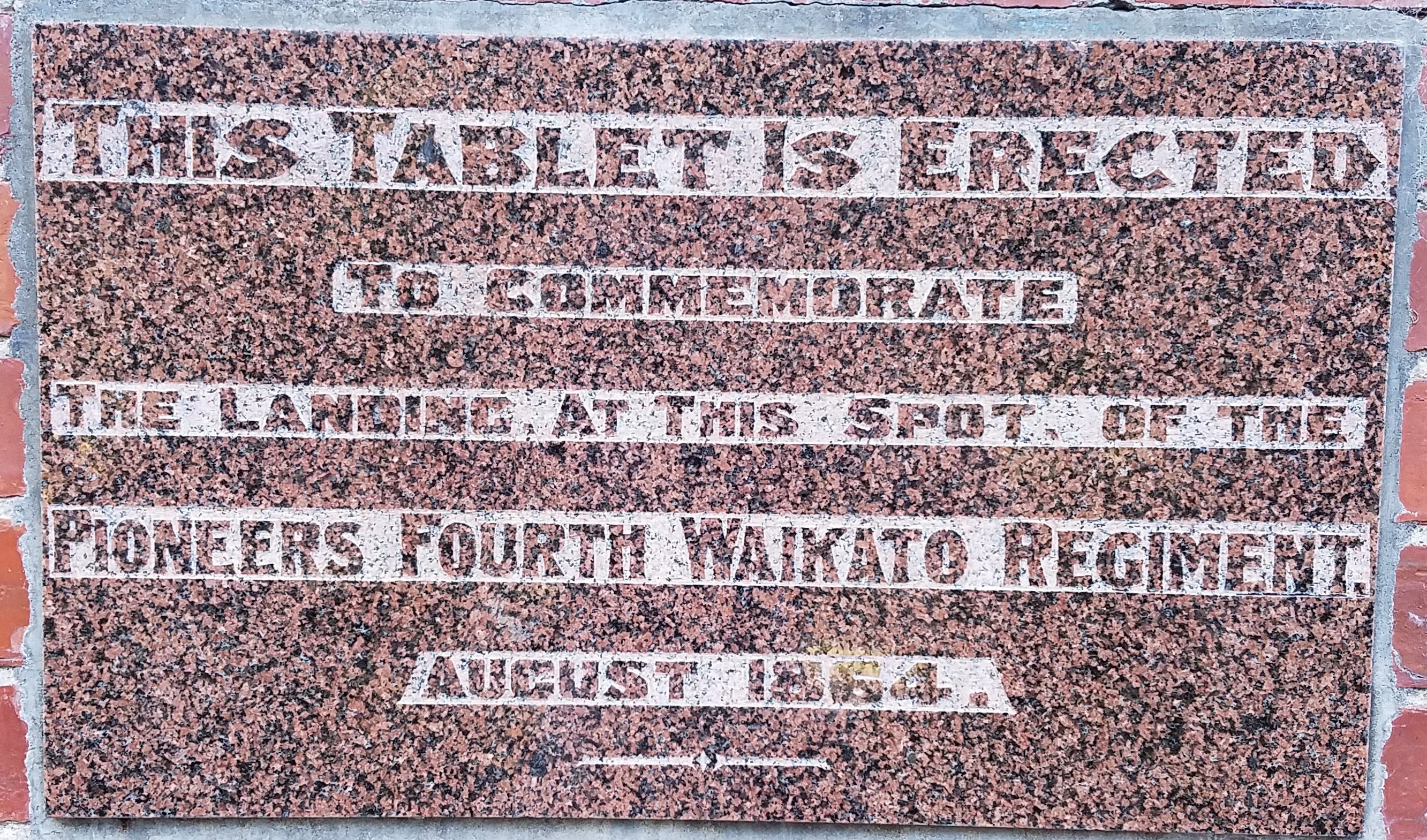

A plaque marking the landing spot of the British militiamen who established Hamilton’s first pakeha settlement

Dawn on ANZAC Day 2020 could not have been more magnificent. As we walked around our community shortly after sunrise, we passed many small memorials erected near letterboxes, along fences, and in our neighbors’ windows. Some included the names and photos of family members who had served in the military, but most were simply a lot of red flowers cut from paper—symbols of the wild poppies that sprang up over hastily dug graves in fields across Belgium during World War I. Over ten thousand of those far-away graves—some marked, some not—belong to New Zealanders.

Sunrise over Lyon Street

A monument at the Ieper (Ypres) – Hamilton Memorial Garden includes the music for The Last Post

ANZAC Day flag: “Lest We Forget”

The poppies blow on Nancy’s shirt

Below: Kiwi patriotism and remembrances on display for ANZAC Day

A few years ago, the Cincinnati Choral Society sang Paul Aitken’s setting of “In Flanders Fields,” the poem written 3 May 1915 by Canadian Army surgeon John McCrae in honor of a friend who was killed in battle near Ypres, Belgium. (Click here to listen to the piece, recorded not by CCS but by the Duke University Chorale, whose director Michael and Nancy sang under in the University of Chicago Chorale forty years ago.) Lieutenant-Colonel McCrae himself would die before the war ended, but his sobering poem ensures that his life, and the lives of the other soldiers he memorialized, will not be forgotten. So does ANZAC Day.

In Flanders fields the poppies blow

Between the crosses, row on row,

That mark our place; and in the sky

The larks, still bravely singing, fly

Scarce heard amid the guns below.We are the Dead. Short days ago

We lived, felt dawn, saw sunset glow,

Loved and were loved, and now we lie,

In Flanders fields.Take up our quarrel with the foe:

To you from failing hands we throw

The torch; be yours to hold it high.

If ye break faith with us who die

We shall not sleep, though poppies grow

In Flanders fields.

Leave A Comment