Since the mid 1830s, whenever The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints has sought to expand into a new country or region of the world, it has sent proselytizing missionaries to preach, convert, and establish branches—the term for local Church units that don’t have enough members to support all the organizations of a fully functioning ward. Newly formed branches are dependent on the missionaries, who act as ministering shepherds to nurture local members and train them in Church policy and administration until they have gained enough experience to assume leadership positions themselves. Several branches may be grouped together to form a district, which is headed by a district president; districts are geography-based divisions of a mission, which is led by a mission president. In times past, mission presidents—like most missionaries serving around the world—came from North America, but by the end of the twentieth century, the Church had become strong enough in the Pacific, Latin America, western Europe, and some parts of Asia for those areas to provide many of their own mission personnel. (At this point, we probably should remind our non-LDS readers that The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints has no paid ministry; most administrative duties and pastoral work are done by volunteers who must support themselves financially by other means.)

In areas where the Church is still becoming established, mission presidents are responsible for directing the work of the proselytizing missionaries and directing the work among the local members themselves. This was the situation in New Zealand during the last half of the nineteenth century. Initially, proselytizing efforts here were largely confined to the Pākehā (European) population, and growth was slow because most Pākehā converts emigrated to America soon after they were baptized. However, when Latter-day Saint missionaries began taking the message of the restored gospel to the Māori in the 1880s, new units of the Church suddenly began to proliferate; between 1880 and 1895, the number of officially organized branches jumped from five to more than eighty. Mission leaders periodically held district conferences where new converts could meet with members of other branches to receive instruction and strengthen each others’ faith. Māori were already accustomed to gathering at their local marae (assembly area) for similar meetings, called hui, to discuss tribal issues and community concerns, so Latter-day Saint mission leaders simply built upon that tradition.

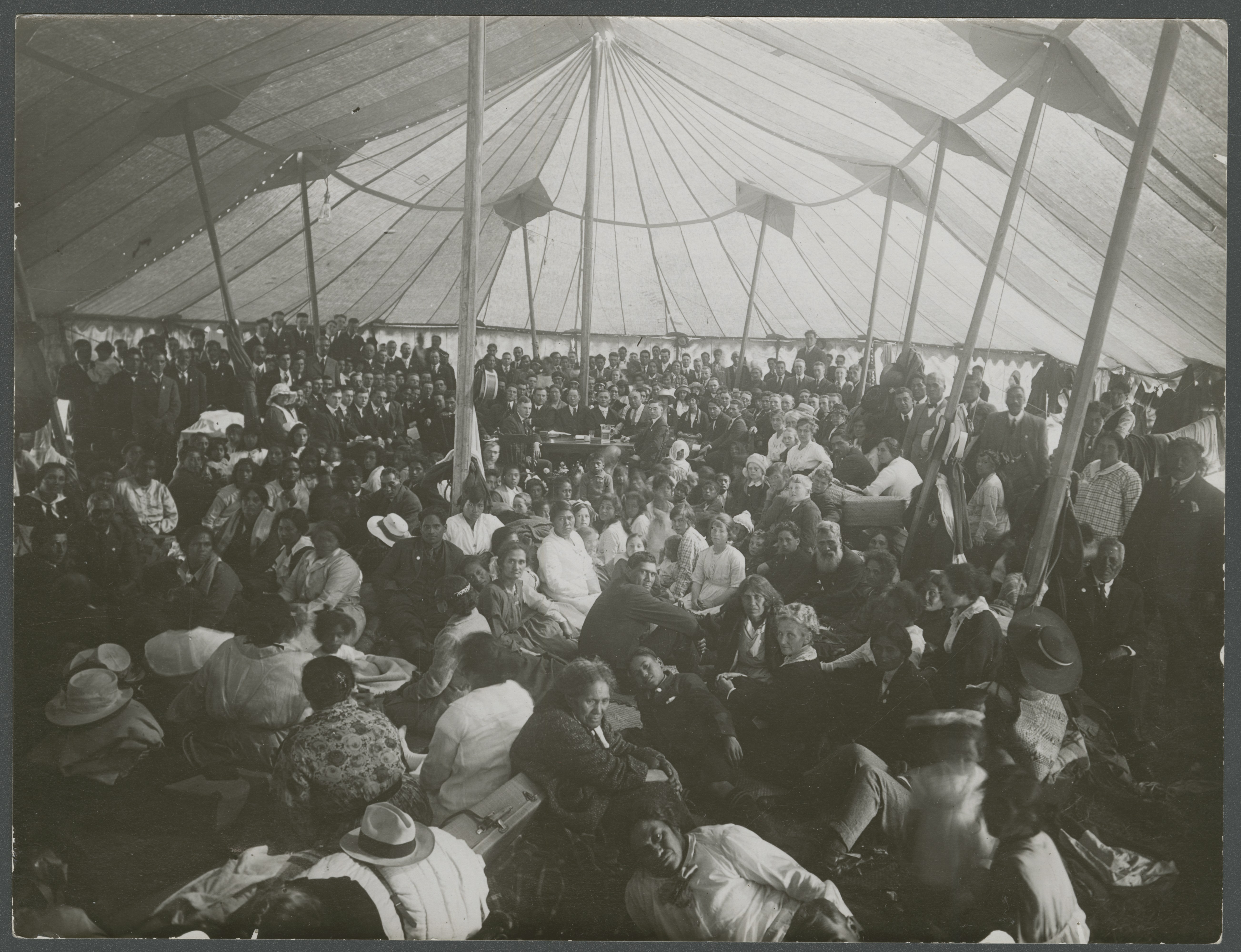

*Hundreds gathered at the 1921 Hui Tau in Huntly to hear David O. McKay, the first modern apostle to visit New Zealand

*Food servers at the 1921 Hui Tau in Huntly

To ensure consistent messaging among so many fledgling Church units and to better fulfill his own ministerial responsibilities, the mission president also held mission conferences, gathering Saints from the entire country to provide instruction, address administrative matters, and build faith. In addition to hearing mission leaders preach, ordinary members had the opportunity to share their testimonies of Ihu Karaiti (Jesus Christ), the prophet Hohepa Mete (Joseph Smith), and Te Pukapuka a Moromona (the Book of Mormon).

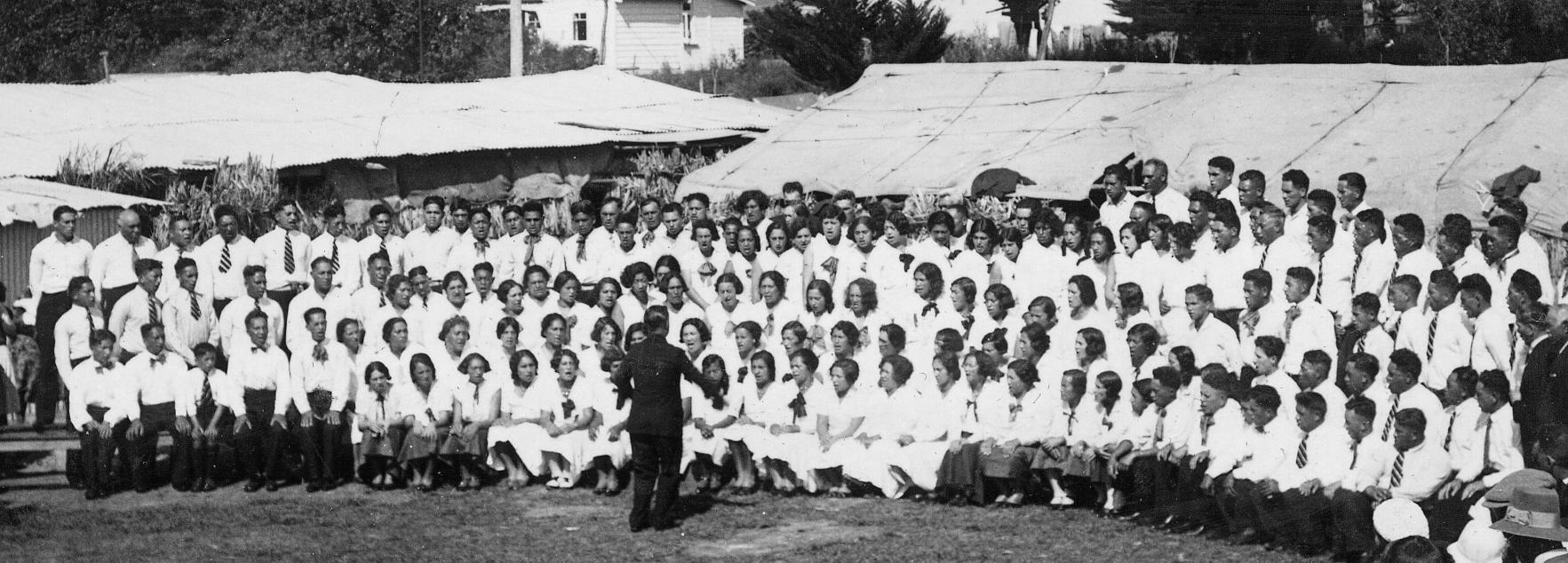

*A choir performance at the 1932 Hui Tau in Nuhaka

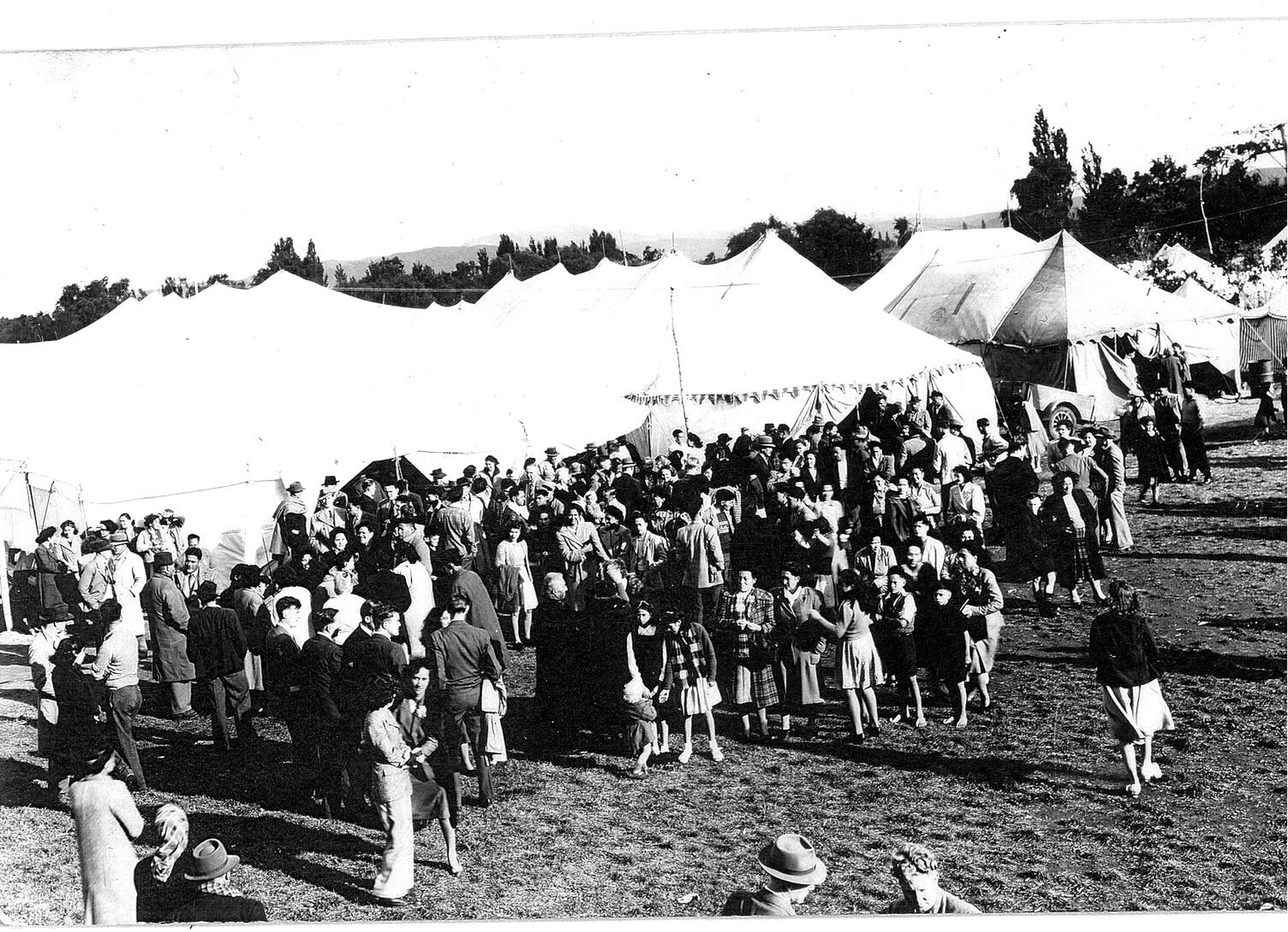

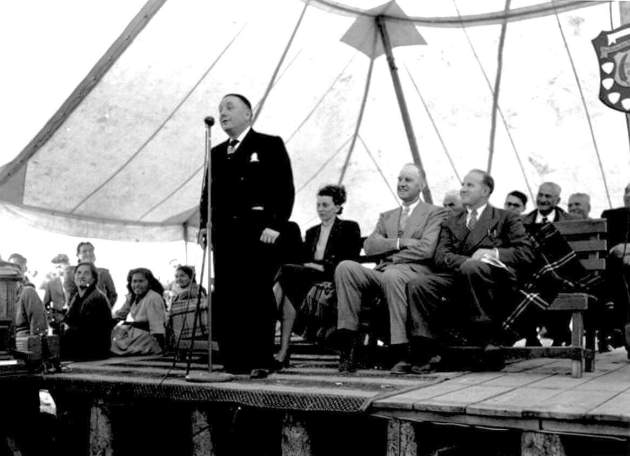

In New Zealand, mission conferences were called hui tau, and were held nearly every year from 1885 until 1958. Though hui tau were always sponsored by the mission, the districts took turns acting as hosts in their various locations around the country. Māori villages whose residents had joined The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints en masse formed the nucleus of most districts, so it was natural to use their marae as hui tau venues. These were big events, attended by hundreds or even thousands of people. To make it worth the trip for those coming from all over the country, the conferences would last four or five days, and the host districts would erect marquees (the British term for circus-size tents) on their marae to accommodate participants not only for plenary sessions but also for meals and sleeping; mats and blankets would be spread on the ground to provide a little comfort. Māori custom demanded that hui tau attenders be treated as honored guests by the host districts, so the proceedings included elaborate traditional welcoming ceremonies, and local members spent weeks gathering and preparing food for their visitors, graciously serving them at no charge.

*1949 Hui Tau in Korongata

*Apostle Matthew Cowley presided over the 1949 Hui Tau in Korongata

In addition to the requisite meetings where prayers were said, scriptures were read, and religious sermons could go on for hours, participants also could engage in a variety of activities that included both the cooperative and the competitive: choral singing, quilting bees, precision marching, track and field events, rugby and other team sports, horseshoes, even tree-felling. One of the most exciting and colorful events of each hui tau was the kapa haka competition. A group from each district, dressed in traditional costumes, presented a set of Māori chants, action songs, and dances based on a historical narrative or central theme, and each group was judged on various aspects of the presentation. Competition was friendly, but stiff, not only in the kapa haka, choir, and athletic contests, but also among the host districts themselves as each tried to outdo what another had done at the last national gathering.

*The start of the precision marching competition at the1953 Hui Tau in Korongata

In short, annual hui tau offered New Zealand’s Church members the opportunity to spend several days in communion with other Latter-day Saints, being fed physically, intellectually, emotionally, and spiritually. But as David O. McKay, then a member of the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles, reported after attending the 1921 hui tau during an official tour, “It was plainly evident that the Māoris had assembled to learn more of the Gospel of Christ, and not merely to be entertained. … The earnestness, faith, and devotion of the audience, the manifestation of the inspiration of the Lord upon the speakers, whether native or European, the excellent music, and the confidence. sympathy, and brotherly love that flowed from soul to soul, all combined to make every service a supreme joy” (David O. McKay, “Hui Tau,” Improvement Era, vol. 24, no. 9 (July 1921), pp.770-77.

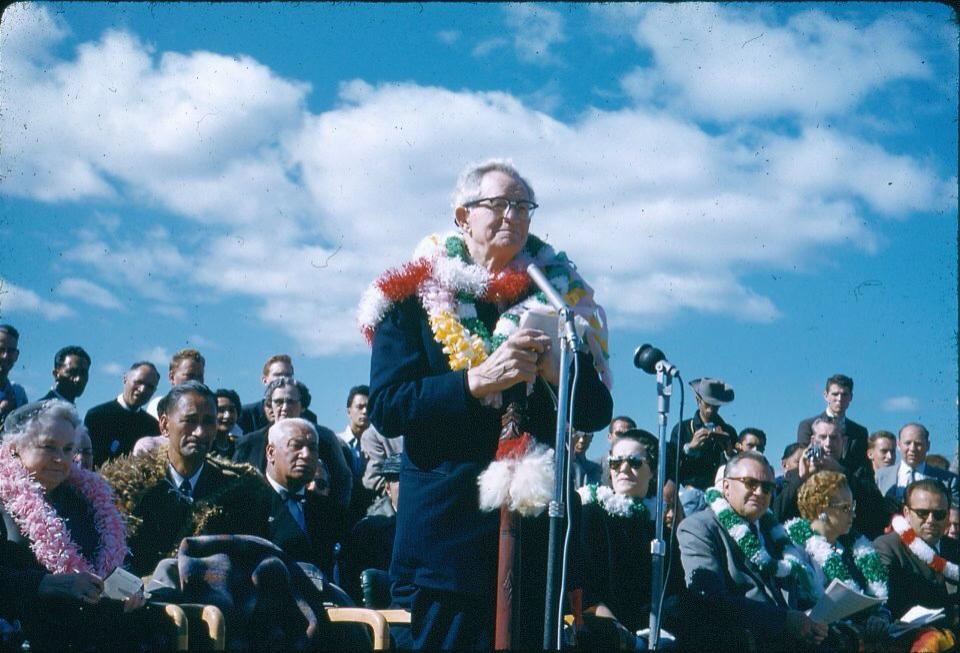

*President David O. McKay addressing the crowd at the 1958 Hui Tau in Hamilton

David O. McKay attended an even grander hui tau in 1958, when more than 5,000 people gathered in Hamilton on the grounds of the newly completed Church College of New Zealand. Now President of the Church, McKay had come to dedicate both the school and the adjacent Hamilton New Zealand Temple. At that point, Church membership in New Zealand exceeded 15,000. The New Zealand Mission was divided to create a second mission, which would be headquartered in Wellington. At the same time, the country’s first stake was organized. Although a stake is similar to a district in that both comprise a number of smaller units within a geographical area, a stake is more autonomous, requiring a strong local leadership base that can handle administrative and pastoral responsibilities without oversight from the mission president. As part of a stake, branches can become wards, led and staffed by local members rather than by missionaries. The formation of the Auckland New Zealand Stake thus was hugely significant because it implied the “coming of age” of Latter-day Saints in the Auckland and Hamilton regions. In addition, it was hugely significant because it was the very first stake to be created outside of North America, emblematic of how successfully the Church had been established in New Zealand.

And so, after 1958, with New Zealand divided into two missions, and the Auckland Stake assuming responsibility for the instruction and welfare of its own members, the annual national hui tau became a thing of the past. For some, that must have been a relief; imagine the logistical challenges and expense involved in hosting a multi-day gathering for several thousand people every year. For many, however, ending the annual hui tau tradition left a cultural and emotional void.

In the years since 1958, stake conferences and occasional multi-stake activities have taken the place of hui tau, but vivid memories of those national gatherings remain. Old-timers recall the pageantry of the precision marching, the friendly rivalry among the district choirs and kapa haka groups, and the excitement of the athletic competitions. Though they appreciate the inspiring talks given by church leaders at stake conferences, they yearn to feel the strong spirit that grew exponentially along with the numbers at those huge, multi-day gatherings of faithful Latter-day Saints.

Today there are more than 115,000 Church members and thirty stakes spread across New Zealand, making the prospect of holding a national hui tau more impractical than ever. But last year, the two stakes in the Northland Region (comprising everything north of Auckland) decided to work together to hold a regional hui tau for their own members. Northland is a sparsely populated area and the traditional homeland of Ngāpuhi, a major Māori iwi (tribe). It’s also home to the only official Māori-speaking unit of the Church, established just last October, and the area has seen a resurgence of interest in the ways Māori culture and the culture of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints intertwine. Hui tau would offer a perfect opportunity to showcase those connections.

Though the coming hui tau was ostensibly only for the Kaikohe and Whangarei Stakes, enthusiasm for such a gathering was not confined to Northland. Soon, people from as far away as Christchurch were registering online for the event, scheduled for 2-4 April 2021: Easter weekend.

As we at the Matthew Cowley Pacific Church History Centre heard about more and more people who were planning to attend, we realized that Hui Tau Kaikohe 2021 was shaping up to be a truly historic event. Our friends Jeff and Kara, full-time missionaries serving in the Church’s Pacific Area Public Communications Department, were planning to go so they could report on the proceedings, and we decided to accompany them simply because we didn’t want to miss the opportunity to participate in such a unique cultural experience. By the beginning of March, the seven other full-time missionaries assigned to the MCPCHC also had decided to go. Rangi and Vic had been invited to speak, and Elder E—who had replaced Elder G (Barry) as director of the MCPCHC in January—received instructions from the Church History Department that all of us were to go to Kaikohe and make official video recordings of the event.

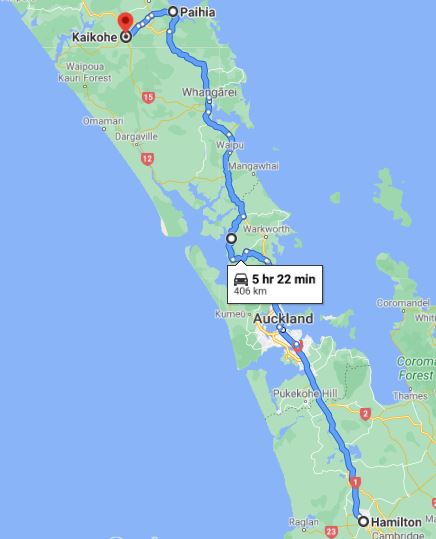

Sister E, who had taken Sister G’s (Eva’s) place as the MCPCHC’s associate director, arranged to rent a vacation house in Paihia to accommodate all nine Church History missionaries; Jeff and Kara booked a hotel room up the street. You may recall that Paihia is the Bay of Islands resort town that we had visited over the Queen’s Birthday weekend in May-June 2020, just as New Zealand was coming out of its two-month COVID-19 lockdown period. (You can read about that experience here.) It’s a 40-minute drive from Paihia to Kaikohe, the site of Hui Tau 2021, but considering that it would be Easter weekend and we had to compete with 3,500 other hui tau registrants for places to stay near a town of less than 5,000 residents, we felt lucky that we found any accommodations at all. Anticipating that restaurant reservations also would be hard to secure and that many small-town bakeries and take-away shops would be closed for the holiday, Sister E also made plans to bring prepared food for all our meals. We would travel in two vans: one owned by Elder and Sister E, and the other borrowed from the Hamilton Mission. We hoped that between the two vehicles there would be sufficient room for all the food and video recording equipment in addition to nine people and our personal gear.

The group agreed to meet at First House, the MCPCHC directors’ residence, at 5:30 a.m. on Friday 2 April, hoping that we could have the vans packed and be on the road by 6:00. The drive to Paihia would take at least six hours, but anticipating that many other travelers also would be trying to cross Auckland on their way to holiday destinations, we wanted to leave plenty of time to reach the rental home, check in, and unload the food before driving to Kaikohe to begin our official duties. The hui tau pōwhiri (traditional Māori welcome ceremony) on the grounds of Northland College in Kaikohe was scheduled to begin at 2:45 p.m.

The group agreed to meet at First House, the MCPCHC directors’ residence, at 5:30 a.m. on Friday 2 April, hoping that we could have the vans packed and be on the road by 6:00. The drive to Paihia would take at least six hours, but anticipating that many other travelers also would be trying to cross Auckland on their way to holiday destinations, we wanted to leave plenty of time to reach the rental home, check in, and unload the food before driving to Kaikohe to begin our official duties. The hui tau pōwhiri (traditional Māori welcome ceremony) on the grounds of Northland College in Kaikohe was scheduled to begin at 2:45 p.m.

Our trip did not get off to an auspicious start. On the evening of Thursday 1 April, Nancy set her alarm for 4:30 so we could be at First House at 5:30 the next morning. What she did not realize was that she had set the alarm for 4:30 p.m. instead of 4:30 a.m., so when her regular alarm went off she was stunned to see that the clock said 6:00—our normal rising time. Moments later, just as she was jumping out of bed, shouting “It’s 6:00! It’s 6:00!” in total disbelief, Michael’s phone began ringing. It was Sister T, calling to ask where we were because everyone else was waiting. What was even worse was that Michael had the key to the mission van, so the rest of the group had not even been able to begin loading all our food and equipment. We showered and finished packing as quickly as we could, but couldn’t help arriving at the meeting spot over an hour late. We offered profuse apologies and then helped load the vans. There was a lot of food!

By 7:00 a.m. we were on our way. The mission van with the two of us and Elder & Sister T (Alan and Wendy) followed the van driven by Sister E (Jo-Ena). She was leading the way because she had grown up in Northland and was familiar with the territory. (We also learned that day that Jo-Ena is the default driver of the E family because her husband, who grew up among the islands of the Marlborough Sounds and learned to pilot a boat long before driving an automobile, is more comfortable at the helm of a ship than behind the wheel of a car.)

Unloading at the Bayswater Holiday Home in Paihia

Traffic on State Highway 1 moved well until we got north of Auckland, so when Google Maps recommended Highway 16 as an alternate route, we took it. The winding, narrower road introduced us to some beautiful bucolic scenery, but may not have saved us much time because we re-encountered the traffic jam in Wellsford, where the two highways meet again. Everyone on both roads seemed to have decided to stop there to use the public toilets. Still an hour behind schedule, we arrived at the Bayswater Holiday Home in Paihia at 1:00. Jo-Ena had prepared a “simple” ham, egg, and pea terrine wrapped in flaky pastry for our lunch, and fortunately, it could be eaten out of hand as we unloaded the vans. As soon as we had stuffed all the perishable food into the Bayswater’s two available refrigerators, we took off for Northland College, and arrived by 2:30.

The manuhiri (visitors) approach tangata whenua (host group)

The first warrior sticks a tao (spear) into the ground as a warning

The second warrior lays a rākau (staff) on the ground

The chief of the visitors raises the leafy branch indicating they come in peace

At a Māori pōwhiri, the tangata whenua (host group; literally, people of the land) send an advance group of their fittest warriors to meet the manuhiri (visitors). The three young perform a wero, an aggressive ritual challenge whose purpose is to determine the intentions of those approaching. The warriors wield ceremonial weapons, contort their faces into fierce grimaces, and shout threateningly to show that they are ready to do battle if the visitors are hostile. The first warrior, representing the god of war, sticks a tao (spear) into the ground as a warning. The way the spear is grasped by a representative of the manuhiri demonstrates whether or not the visiting group is coming in peace. If the visitors signal friendly intentions, the second warrior approaches less aggressively, lays a rākau (staff) on the ground, and then returns to his own group after the manuhiri again responds calmly. Finally, the third warrior, representing the god of peace, presents a rautapu (leafy branch) to indicate that the manuhiri may now enter the marae. A call and response ensues, with a female kaikaranga (caller) from the tangata whenua issuing a karanga (ritual call) to invite the visitors to come forward; a kaikaranga from the manuhiri responds in kind as the guests move onto the marae.

In the case of the Latter-day Saint hui tau in Kaikohe, the tangata whenua comprised about 150 people from the two host stakes, assembled under a marquee on one side of the Northland College athletic field. We were part of about 500 manuhiri assembled on the edge of the field during the wero. As the wero ended and the visitors began moving into the space that would serve as the marae for the weekend, we enjoyed one of the perks of being missionaries from the Pacific Church History Centre: because we were recognized as being part of Rangi and Vic’s entourage (everybody knows and respects “Aunty Rangi and Uncle Vic”), we were led through the crowd to some of the choicest seats in the section reserved for honored guests. From there, we had a good view of the rest of the afternoon’s events.

The host group offers its speeches

The visiting group offers its speeches in return

Once everyone was seated, the whaikōrero (speeches) began. One after another, eight or ten men from the tangata whenua stood and spoke in a dramatic, declamatory style, reminding us of African-American preachers like Martin Luther King and T.D. Jakes. After each speech, someone else would rise to lead the tangata whenua in a waiata (song). When the host group was finished, another eight or ten men from the manuhiri stood to give their own florid speeches, each followed by a waiata performed by their group. Two or three hours later, when it appeared that no more representatives from the manuhiri intended to speak, the man from the host group who had begun the speechifying concluded with a final whaikōrero.

What were all the speeches about? We’re not really sure, because the proceedings were conducted almost entirely in te reo, the Māori tongue. Other than the basic outline, the content of a powhiri is not set; any number of respected males from either the tangata whenua or the manuhiri may rise and say whatever they want, and the waiata are similarly extemporaneous. But because this was a gathering of Latter-day Saints, and because we have learned to recognize at least a few Māori words and phrases, we got the gist. One phrase we heard over and over was “Haere mai!” (the equivalent of “Come one, come all!”) and “Nau mai!” (”Welcome!”). Often, these were combined with the names of the places or iwi from which visitors had come: “Haere mai, iwi katoa!” (“Come, all tribes!”) “Nau mai, Kirikiriroa! Nau mai, Rotorua! Nau mai, Tauranga!” and even “Nau mai, Utah!”

Several speakers obviously viewed this event not simply as a hui tau but as a huihuinga o Iharaira—a gathering of Israel. Many Māori regard themselves as mōrehu (a “remnant”) of the ancient House of Israel; Latter-day Saints also believe that we are children of Israel because we have made the same covenant with God that Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob made. We loved being addressed as whanau, a word that literally means family, but also is the Māori equivalent of “brothers and sisters,” the phrase Latter-day Saints typically use to address a congregation. Other words repeated frequently as speakers described what they were feeling included wairua (spirit) and aroha (love). It also was clear that many of the whaikōrero were testimonies that kei te ora a Ihu Karaiti (Jesus Christ lives) and expressions of gratitude for te rongo pai (the gospel). The final whaikōrero, given by President B of the Kaikohe Stake, included a reminder in English that we had met not just to celebrate our heritage as Latter-day Saints (Māori or otherwise) but to celebrate Easter: the triumph of Christ over sin and death.

The hosting and visiting chiefs press noses in hongi to welcome each other

The powhiri came to an end as all the representatives of the tangata whenua who had spoken lined up to formally greet all the representatives of the manuhiri who had spoken with hariru (handshaking) and hongi (nose-pressing). After that, the crowd—which during the course of the afternoon had grown to about a thousand—began to engage in a myriad of more informal greetings.

In keeping with Māori and hui tau tradition, the tangata whenua—in this case, the members of the Kaikohe and Whangarei Stakes—offered to provide dinner for all comers that first evening. Because our group had registered in advance, we received wristbands entitling us to pick up a portion of the hāngi (food cooked in an underground pit lined with heated stones) that was being prepared. Skeptical about the prospect of “competing with thousands of people for kai [food],” Jo-Ena had put some sandwich buns, corned beef (known here as “silverside”), coleslaw, and plastic wrap out along with the terrine we ate for lunch and urged us make ourselves a sandwich to take along so that in case the hāngi was insufficient for the crowd, we wouldn’t starve. It had been announced at the end of the powhiri that the hāngi would be served at 6:00, but when 6:00 came and went with no hāngi in sight, Nancy began looking around for Michael’s backpack, where she had deposited the sandwich she had assembled for herself before leaving Paihia. She was exceedingly disappointed to learn that not only had Michael left his backpack in the van, but also that the member of our party who had the key to the van was nowhere to be found.

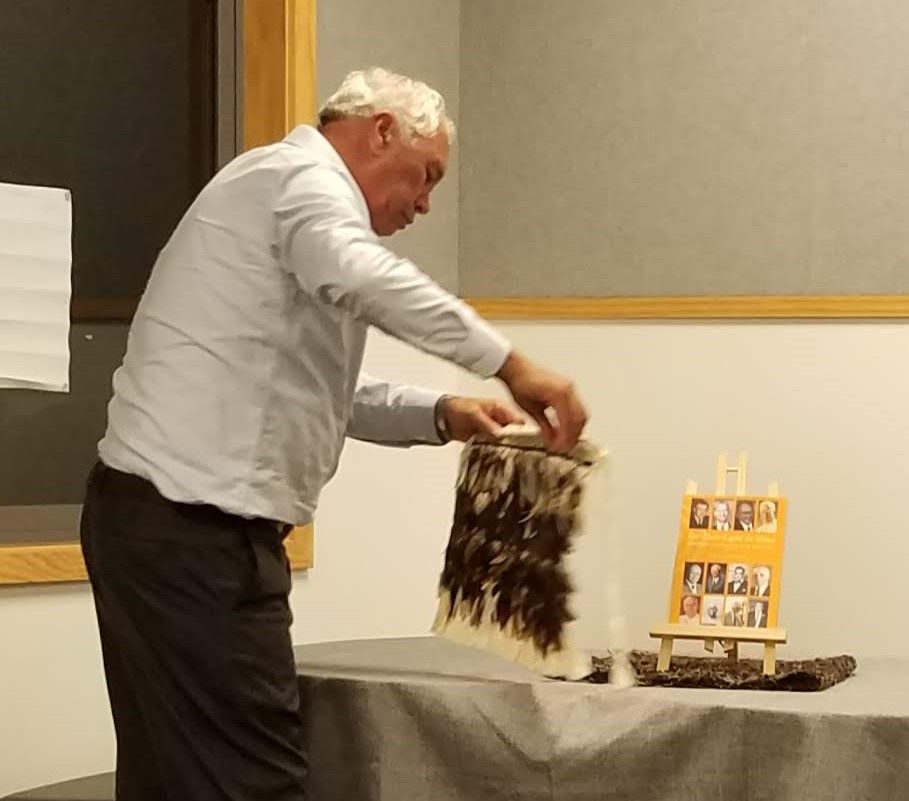

Selwyn K unveils his new book

About 6:45 p.m. we received word that since dinner had been delayed (estimated serving time was now 8:00), an auxiliary event originally scheduled for Saturday was being moved up to 7:00 on Friday. This was the launch of the third volume in a series of books about significant individuals in the history of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints in New Zealand, and the Church History missionaries were expected to attend. The book’s editor, Selwyn K, had invited several contributing authors to join him for the “unveiling” and be on hand to sign copies afterward. We expected the ceremony to take maybe fifteen or twenty minutes. We were wrong. Before the book was literally unveiled (a copy placed on a table easel had been covered with a miniature korowai [traditional Māori cloak]), each of the authors took a turn to speak, much as the speakers at the powhiri had done—and at about the same length. They paid tribute to the outstanding men and women they had written about, and because the authors were descendants of their subjects, they shared some personal stories. We were grateful that most of these kōrero were delivered in English, including one by Jared R-C, the husband of our Church History Department area manager, whom we had met during our visit to Christchurch on New Year’s Day. He had written about his grandfather, who had been a member of the All Blacks national rugby team in the 1940s and later a member of Parliament.

When we were finally able to make our way out of the classroom where the book unveiling had been held, we learned that the hāngi still was not ready to eat and would be served the next day. However, plastic take-away containers filled with individual portions of the steamed pudding and custard sauce that had been prepared for dessert were distributed to anyone with a wristband. For most of our group, the pudding had to suffice as dinner until we got back to Paihia. It seems that Nancy was the only one who had heeded Jo-Ena’s earlier instructions to make ourselves a sandwich, and thus she was the only one who was able to enjoy a complete, satisfying meal before 9:30 p.m. When we reached the Bayswater Holiday Home, the silverside, coleslaw, and buns were put out on the dining table again. Jo-Ena had made enough so we could invite some other hungry senior missionaries to join us for our late-evening nosh: Jeff and Kara, plus Wendy’s brother George and his wife, Terry. The latter couple had received special permission from their mission president to come to hui tau from Wellington, and it was fun to visit with them.

Late dinner at the Bayswater Holiday Home

Although the Bayswater had ten beds, only eight of them were located within actual bedrooms. This meant that at least one of the nine of us would have to sleep in a public area. Michael and Nancy agreed that Diane shouldn’t have to be the one to sacrifice her privacy just because she doesn’t have a bed partner, so we offered to take the twin beds located in the hall. Michael, prone to midnight wandering, decided to move his bed to a far corner of the upstairs lounge so he wouldn’t disturb anyone else. Nancy was quite happy to have a bed all to herself and never noticed those who passed by on their way to the toilet during the night.

Reflecting on our first day of Hui Tau 2021, we noted two things that especially impressed us. First, we were awed by the number of people in attendance who spoke te reo with fluency as well as exuberance. Fluency has not come easily to most Māori living today. Because te reo was officially suppressed for nearly a hundred years, today’s adults did not grow up speaking or even hearing their ancestral language. Some of our older museum volunteers remember being punished if they spoke te reo at school. Efforts to reclaim the language of New Zealand’s first inhabitants did not begin until the 1980s, so most adults who speak it now have had to learn it the hard way. They are fiercely and justly proud of this expression of their heritage, and we experienced a little of the thrill they must have felt to have so many Māori speakers gathered in one place.

The other thing that left a great impression on us was the warm, welcoming spirit that enveloped all who attended. We witnessed hundreds of joyful embraces as friends and whanau greeted one another, and we, too, experienced the joy of being embraced by people we knew, but also by people we’d never met before. Everyone was so eager to make connections, to acknowledge that all of us are indeed whanau—brothers and sisters—because we are children of God.

*The historic images in this post appear courtesy of the Kia Ngawari Trust and the Church History Department

What a great primer for a non-LDS! Thank you for your description of a spirit-filled gathering, however short on hangi – at least you had pudding for dinner!