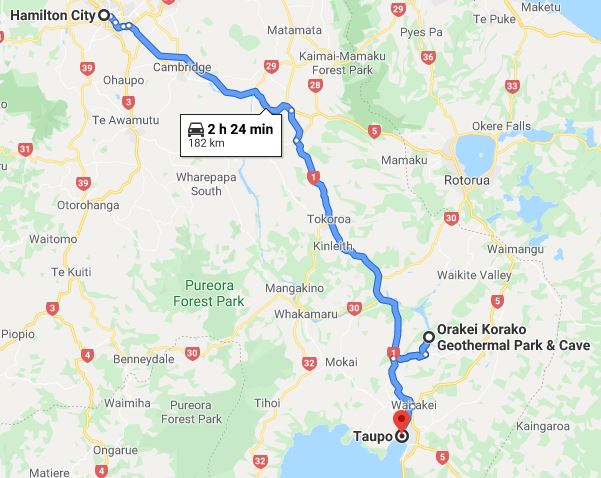

As Elder and Sister G (Barry and Eva) were planning a weekend trip to take care of some church history business near Napier, a town on the east coast of the North Island, they proposed that we head out after church on Sunday 15 March and meet them that afternoon in Taupo, a lake resort town halfway between Napier and Hamilton. We could have dinner together and stay the night, and then spend Monday seeing the sights and relaxing by the lake before returning to Hamilton in the evening. It didn’t take a lot to convince us to go along with the idea.

Then just two days before our trip, we learned that due to the looming COVID-19 pandemic, The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints had decided to suspend all in-person meetings and activities worldwide until further notice. It was a stunning announcement with far-reaching implications, but at the moment we regarded it as an unexpected gift. Now we would be able to leave Hamilton much earlier on Sunday, and thus have time to do some exploring along the way before meeting Barry and Eva in Taupo. Realizing that without church meetings, Sister E (Diane) would be more alone than usual that weekend, we invited her to come along with us. It didn’t take a lot to convince her to accept our invitation.

With the suspension of regular Sunday meetings, Church leaders had granted permission for qualified priesthood holders to administer the sacrament (the ordinance that other Christians call “communion”) in their own homes. Most Latter-day Saint men age 16 and up are ordained priests and thus are authorized to administer this ordinance, so most families would be able to hold their own sacrament services. However, households with no resident priest (such as Sister E’s) would either have to make other arrangements or go without that weekly opportunity to formally remember the Savior and renew their covenants with him. So at 9:30 on Sunday morning, we met Diane at her flat and the three of us had our own little sacrament service, with Michael officiating. It was a nice way to start our day on a beautiful late-summer morning.

Lunch on the veranda at Orakei Korako

Before 10:00 we were off, and by noon we had reached our first stop: Orakei Korako, an active geothermal area located in a valley north of Taupo. Because we arrived at lunchtime, we found a table on the veranda outside the visitors center and ate the lunches we had packed, enjoying a beautiful, peaceful view of Lake Ohakuri before we began our explorations. The man-made lake is a popular spot for boating, waterskiing, and sport fishing. Lots of folks were out taking advantage of continuing warm, dry weather that day. Among dozens of cars in the parking lot, we counted fourteen “caravans” (the Kiwi term for self-contained camping vehicles).

Orakei Korako is Maori for “Place of Adorning,” so called because Maori women used a secluded cave near the hot springs as a sort of beauty spa

Maori occupied the area long before Europeans discovered Aotearoa (the preferred Maori name for New Zealand), using the hot water for cooking and bathing even though, at the time, this stretch of the Waikato River was dangerously swift. In addition to bubbling springs, Orakei Korako boasts nearly three dozen active natural geysers—more than any other geothermal park in New Zealand—and a series of stepped mineral deposits not unlike the Pink and White Terraces of Te Wairoa, although not as big nor as beautiful. (You can see a picture of the Pink and White Terraces and read our post about Te Wairoa here.)

After the 1886 eruption of Mount Tarawera completely transformed the local landscape, most Maori abandoned the “Hidden Valley” of Orakei Korako, which was on the earliest known route between Taupo and Rotorua. The few who stayed in the area went into business ferrying European tourists across the Waikato River in dugout canoes so they could see the geysers and colorful, steaming pools. In 1937, a group from Rotorua obtained a lease on the land, improved the road, and opened a full-service tourist resort.

However, due to an extreme electricity shortage following World War II, the New Zealand government developed a plan to build several hydroelectric dams along the Waikato River, including one downstream of Orakei Korako. That dam was finished in 1961, creating Lake Ohakuri, the first man-made lake in New Zealand. Unfortunately, the reservoir raised the water level at Orakei Korako sixty feet, ruining two-thirds of the area’s active geothermal features: approximately two hundred alkaline hot springs and seventy geysers, including Minginui Geyser, which had been the equal of Steamboat Geyser in Yellowstone National Park. (Steamboat, now unquestionably the world’s tallest active geyser, is capable of sending 300-foot plumes of water and steam into the air.) The Orakei Korako Geyser, which lent its name to the whole region, also was among the world’s tallest, occasionally erupting up to 180 feet. Some of these submerged thermal features still discharge, but are evident only as gas bubbles rising from vents in the lake bed. (The New Zealand government has since learned to conduct impact studies and seek public input before proceeding with major projects like dams.)

About 5 million gallons of water flow over the surface of Emerald Terrace into the lake every day

Visitors reach the geothermal site by ferry

When we had finished our lunch, a small ferry was waiting to take us a short distance across the lake to the geothermal area. The part of Orakei Korako that is currently open to the public consists of three terraces. The lowest, called Emerald Terrace, extends 115 feet below the surface of the lake.

Emerald Terrace

Diamond Geyser didn’t erupt during our visit

Despite the name “Emerald,” this terrace is characterized by orange microbial “mats” formed by millions of microscopic organisms that thrive in warm water (115°F) with a neutral pH (7.6). As the microbes photosynthesize, they emit bubbles of oxygen that make the water appear fizzy. The Emerald Terrace also includes the Diamond Geyser, whose unpredictable eruptions can last from a few minutes to many hours, ejecting boiling water as high as 30 feet. Sunlight reflecting from the spray makes it sparkle like diamonds—hence the name.

Cascade Terrace

Sapphire Geyser

The next level up is called the Cascade or Rainbow Terrace. It features the Sapphire Geyser, which erupts every two to three hours, and the Hochstetter Pool, named for Austrian pioneer geologist Ferdinand von Hochstetter, who visited the area in 1859. Some microbial mats on this terrace are brown and black, due to different organisms that prefer a cooler temperature (95°F) and a slightly lower pH (about 7).

Golden Fleece Terrace

The third terrace is called the Golden Fleece, or Te Kapua (The Cloud) in Maori. Sixteen feet high and 130 feet long, its delicate white crystalline coating was formed by deposits from mineral springs that stopped flowing hundreds of years ago—and then inexplicably started again in 2001.

Artist’s Palette

At the top of this last terrace is the Artist’s Palette, a 10,000-square-meter mineral deposit formed about 10,000 years ago. It is covered with clear blue alkali chloride pools and irregularly erupting geysers. The amount of hot water discharging from the springs onto the terrace constantly fluctuates, so sometimes the water level is below the surface of the terrace, while at other times most of the terrace is submerged.

Rautapu Cave

Farther along the track above the Artist’s Palette is Ruatapu (Sacred Cave), one of only two caves in the world known to exist in a geothermal field. Ruatapu is 150 feet long, with a 75-foot vertical drop to a shallow pool known as Waiwhakaata (Pool of Mirrors). This is where the Maori women came to “adorn” themselves.

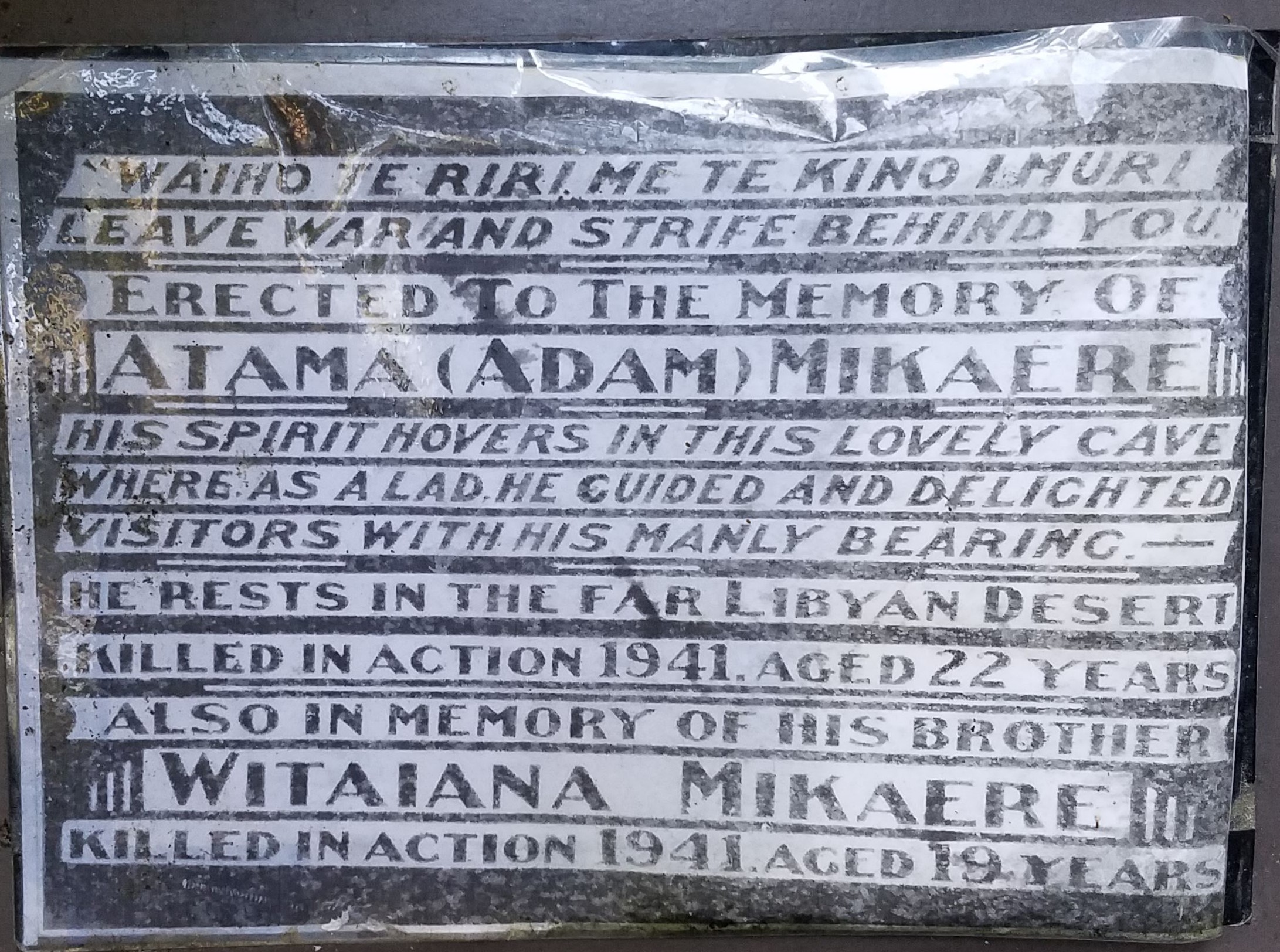

Memorial to a guide killed in WWII

It’s also the site of a memorial to a young Maori man who guided visitors around Orakei Korako before he was killed in action during World War II. According to the inscription, his body “rests in the far Libyan desert,” but “his spirit hovers in this lovely cave.”

Mud pools

Beyond the cave we saw a number of pools of liquid clay, formed over time as acidic water gradually breaks down the underlying rock. Bubbles go bloop-bloop on the surface as carbon dioxide is discharged through numerous small vents at the bottom. The mud pools, which always occur above the water table, usually simmer fifteen to twenty degrees below the boiling point.

The cleverly named restrooms at Orakei Korako

After hiking a track that not only was mostly in full sun but also passed by steaming thermal vents, we were ready for some cool refreshment. We ferried back across the lake to the resort where we could get a drink and relax in the shade of the veranda before we resumed our journey.

Our next stop was Aratiatia Dam, another of the nine hydroelectric generating stations on the Waikato River. If you’ve seen The Desolation of Smaug, the second film of The Hobbit trilogy, you may remember the scene in which Bilbo and his party escape from attacking orcs by barreling down raging rapids in, well, barrels. That scene was shot just below Aratiatia Dam. (If you didn’t see the movie or need your memory refreshed, you can watch the scene here; the castle battlements and surrounding forest are, sadly, only CGI effects.)

The Waikato River just below the dam when the gates are closed

Open gates of the dam

The Walkato River just below the dam when the gates are open

Aratiatia is the first dam downstream from Lake Taupo, where the Waikato begins, and the dam had a huge impact on the river’s famously wild rapids: when it was built, the rapids basically disappeared. As a concession to naturalists and whitewater enthusiasts, however, the gates of the dam are opened three or four times a day, restoring the rapids to their normal flow—for a few minutes, anyway. We got to the dam in plenty of time for the 4 p.m. gate opening and thus were in position for a terrific view before too many other onlookers arrived. The whole event from the dramatic opening of the gates to the final calming of the water takes only about twenty minutes. The swans floating on the reservoir behind the dam didn’t seem to notice the change at all.

Rapids at full force with the gates fully opened |

Receding waters once the gates were closed |

Rapids with gates fully closed |

Our last stop before driving into Taupo was at Huka Falls, the largest waterfall on the Waikato River. (Huka is Maori for foam, which is appropriate given what the scene looks like at the final drop.)

Waikato River streaming down the narrow canyon

Huka Falls

As it flows out of Lake Taupo, the Waikato averages 325 feet across (more than the length of a football field), but just upstream from Huka Falls all that water gets funneled into a canyon only 50 feet wide. The falls begin with a set of small drops that total about 26 feet, then the final drop is about 20 feet, so it isn’t the height that impresses visitors. Rather, it’s the volume of water flowing over those drops: often 60,000 gallons per second. (Watch that clip from The Hobbit again to get the idea.)

Lake Taupo was formed in a caldera, a kind of volcanic sinkhole

Lake Taupo was formed by a huge volcanic eruption about 27,000 years ago. Geologists report that the volcano has erupted 28 times since, most recently in 181 AD. According to Maori legend, a prominent tohunga (wise man) named Ngatoroirangi lost patience with the area’s harsh winters and poor soil, so he pulled up a totara tree and threw it into the dormant caldera, hoping to generate a forest. The tree landed upside down, so instead of taking root, the branches pierced the earth and brought water gushing out of the ground, filling the caldera and creating the lake. Today, Lake Taupo is the largest lake in New Zealand, covering 238 square miles (about the same size as Singapore). With an average depth of 360 feet (610 feet at its deepest point), it contains fourteen cubic miles of water.

Maoris settled the land around the lake nearly seven hundred years ago, but the first Europeans did not arrive until the 1860s. As previously mentioned, the soil was not very productive, so pakeha farmers didn’t take much interest in the region until the 1950s, when artificial fertilizers were introduced. However, Taupo’s growth has been generated less by agriculture than by recreation and tourism.

Hilton Lake Taupo

Barry had reserved rooms for us at the Hilton Lake Taupo, which had begun its life in 1889 as a gracious Victorian hotel called The Terraces. About fifteen years ago, Hilton bought the property and annexed the adjacent apartment building, then upgraded the whole complex to Hilton standards. Our rooms were in the more modern section so they didn’t have the vintage character of the original building, but they were very nice nonetheless. After we checked in, Barry called to tell us that he and Eva were about thirty minutes away, so we had time to relax on our terrace and appreciate the view while Michael consulted TripAdvisor for dining recommendations.

Tejano Bar and Grill

Awaiting our dinner

Once Barry and Eva had checked in, the five of us drove together downtown to what sounded like a good Mexican restaurant, Tejano Bar and Grill. The gourmet tacos and burritos we ordered were indeed good, exceeding our expectations. The tacos stuffed with fried cauliflower, shredded red cabbage, and “spicy sauce” turned out to be our favorite. We wouldn’t give the restaurant high marks for service, however, because by the time Diane, Nancy, and Michael’s orders arrived, Barry and Eva had already finished eating.

As we rode back to the hotel after a stop at Luna’s Gelateria, Barry’s voice took on an earnest tone. “Now, about tomorrow, he said. “The main question is: What shall we do for breakfast?”

Having stayed at the Hilton Lake Taupo previously, Barry could recommend the hotel’s breakfast buffet. “It’s excellent, but pricey,” he said. We decided to take a look at the menu before we went on to our rooms that evening to help us make a decision. When we asked the host for a breakfast menu, he mentioned that if we booked a table for breakfast by 9:00 p.m., we could get a $10 per-person discount. Knowing that made the prospect seem less pricey, so after perusing the next day’s offerings, we stopped at the reception desk and put our names on the list for the breakfast buffet.

During our walk before breakfast, we could see steam rising from hot springs in the ravine behind the hotel

Breakfast buffet at the hotel

Just as Barry had foretold, the buffet was excellent. Both he and Michael ordered Eggs Benedict. They were happy to see that the dish was served on only one half of an English muffin, allowing them more stomach capacity to enjoy the rest of the spread. Of particular note were the fresh kiwi juice and some very light raisin muffins.

The day was overcast but not too cool—perfect for outdoor exercise, but not so great for stunning photos of the scenery

After breakfast we were ready to hike the Great Lake Pathway (also called Lion’s Walk), a trail that follows the western edge of the lake. We drove south to Five Mile Bay and parked, hiked to Wharewaka Point, then turned around and walked back to the carpark. Using the term “hike” here may convey the wrong impression because the path is paved and mostly flat. It’s as popular with cyclists as with pedestrians, so our greatest challenge was avoiding collisions with travelers on wheels. (To their credit, cyclists in New Zealand almost always use a bell or call out a warning as they approach.) We also enjoyed watching a number of parasailors floating above the lake and the surrounding mountains.

Nancy does her part to save drought-stricken plants

A conservation group supplied buckets for watering new plants along the path

The terrain around Lake Taupo is fairly arid, with desert shore vegetation that reminded Nancy of that along the beaches she used to frequent in Southern California. Along the strip of sand between the Great Lake Pathway and the water, conservationists are trying their best to reintroduce native plants and grasses. At several points along the way, they had placed buckets inscribed with a plea to walkers: “Please help us save our thirsty plants.” We spent about half an hour contributing what we could to the effort, but there were so many drought-stricken little shrubs and saplings that we could have spent the whole morning hauling water from the lake and still served only a fraction of them.

About 11:30 we headed back into the town of Taupo to take some time to shop. Eva was looking for a sweater, so we followed her into Jumpers (which is what Kiwis call sweaters) and loved fingering its super-soft merino-possum knitwear. Too bad the prices were astronomical. Michael found a better deal at the Marmot outlet: a good raincoat marked down 50 percent. Assuming that drought conditions won’t last forever, he should get a lot of use out of it. Nancy tried on a pair of voluminous, heavy-cotton harem pants that were hanging on a clearance rack in another store. Although she loved the way they looked and felt, she realized that because they didn’t meet the guidelines for acceptable missionary attire, they’d have to languish in her closet for two years, and then she wasn’t sure she’d be able to squeeze them into her luggage for the trip home. Sadly, she put them back on the rack.

Replete Cafe

Before the five of us had separated for shopping, we agreed to reconvene at 1:30 for lunch at the Replete Cafe, a deli/bakery counter with outdoor seating. The array of artisan sandwiches, soups, and salads in the glass “cabinet” perfectly suited our alimentary needs.

Taupo SuperLoo

Before starting the trip home, we visited the SuperLoo in Taupo’s central square. This is a place where visitors not only can use the toilet, but also can rent a towel and take a hot shower (but please, no laundry or dishwashing). Our group had to search pockets and purses to find enough 50-cent coins to pay the per-person entry fee—not an easy task for those of us who have been leading a largely cashless existence since we arrived.

The road back to Hamilton went through Tirau, so of course we had to stop at One Road for another taste of its fabulous ice cream. How disappointed we were to learn that the shop was going to be closed all winter! Unless we could make it back to Tirau again before Easter, we would have to wait until mid-October for our next sample of One Road’s ice cream. Had we known that within a few days, every ice cream shop in New Zealand would be closed until further notice due to COVID-19, we might have asked for extra scoops.

Leave A Comment