One morning at the beginning of March, a couple from Germany visited the museum at the Matthew Cowley Pacific Church History Centre. They had come to New Zealand to further the woman’s research for a book she was writing on Maori history and culture. As she explained to the volunteer guide who greeted them, the question that had brought her to our museum was this: Why have so many Maori joined the Mormon Church?

Not only did Isabella, the guide, know exactly which displays would help the woman discover answers to her question, but she also was well prepared to offer additional insights, because Isabella is a descendant of some of the earliest Maori converts to the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. Neither of us was there to hear exactly what she told the German couple, but it’s likely that she shared some of the following stories from the history of her people.

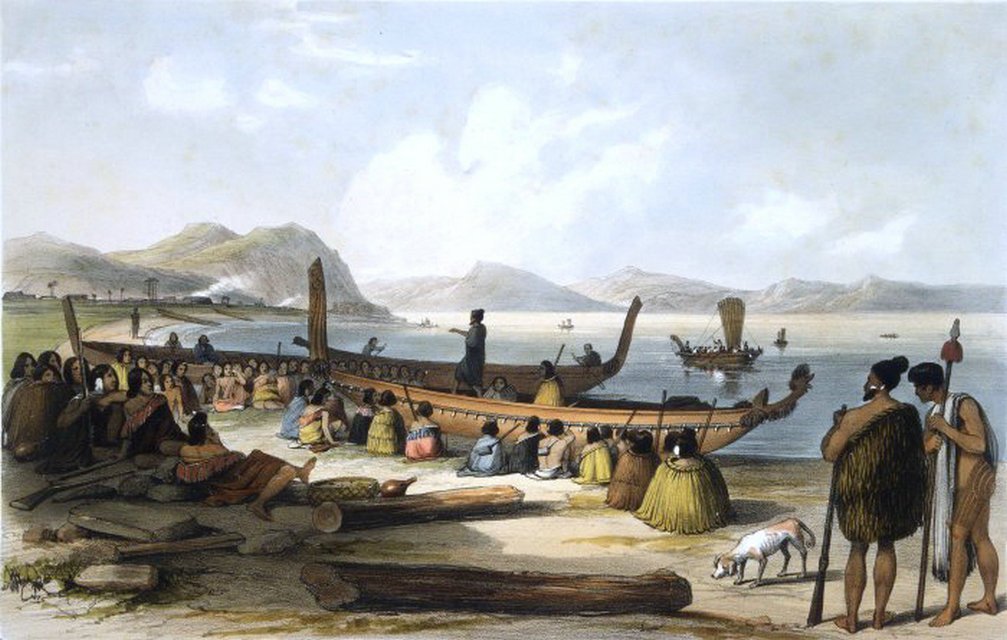

Depiction of the Maori arriving in their waka

Historians agree that the Maori came to the islands we now call New Zealand around the thirteenth century. They found the land unpopulated by other humans, and called it Aotearoa, Land of the Long White Cloud. They came in different groups, arrived in different waka hourua (voyaging canoes), and landed in different areas, but it seems clear that they all originated from the same area of Polynesia because they shared physical characteristics in addition to a common language and customs. What is less clear is where they came from. According to Maori tradition, the waka fleet came across the Pacific Ocean from another island called Hawaiki—but no one is certain exactly where Hawaiki was located.

Abel Tasman

Not long after Aotearoa was discovered by white men—initially by Abel Tasman in 1642, but more significantly by James Cook in 1769—the islands became a destination for Christian missionaries from Europe bent on converting the “heathen” to their own way of life. The Maori gladly sent their children to the schools the Pakeha established to teach them to read, but they were not attracted to the Europeans’ conception of God as a demanding schoolmaster, withholding rewards from all but the best students and ready to whip unruly pupils into submission. They also were unimpressed with white men who professed to be Christian but seemed less focused on moral living than on commercial success. Over the decades, however, as the Pakeha missionaries began to place more emphasis on the spiritual benefits of their religion than on its “civilising” aspects, the Maori slowly began to respond. The people of Aotearoa also were intrigued by the teaching of some of these Bible-believers that they (the Maori) were descendants of one of the lost tribes of Israel.

James Cook

Problems arose, however, when the Anglicans who had initiated the Christianizing of the Maori were joined by Wesleyans, and then by Roman Catholics from France. As the sects began to compete with each other for converts (the French adding a component of bitter national rivalry to the religious one) some Maori rangatira (chiefs) took sides, declaring that their iwi or hapu (tribes or sub-tribes) would henceforth be Anglican, or Catholic, or whatever, exacerbating conflicts that already existed among some tribes. Other rangatira embraced Christianity in general, but allowed individual whanau (extended families) to decide which ministers to follow. Still others remained entirely aloof.

Meanwhile, in more than one hapu across New Zealand, an intriguing phenomenon was occurring among Maori who had heard the Christian preachers but weren’t sure what to make of what they taught. Valuing what they learned from the Bible but confused by the ministers’ differing interpretations, the people sought help from their tohunga—wise, spiritual men recognized by the community as holy oracles.

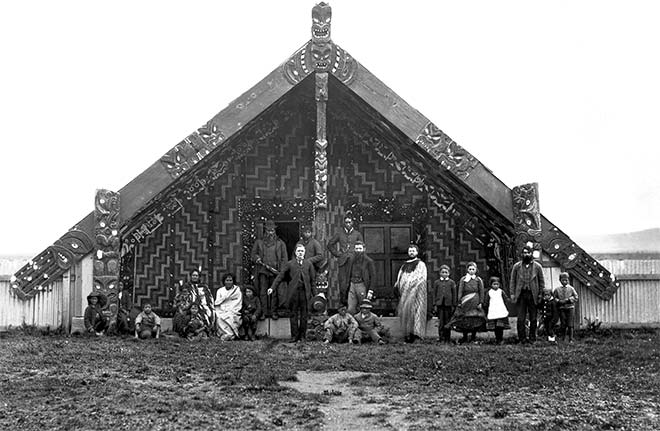

In March 1881, at a hui tau (tribal conference) of the Ngati Kahungunu held at Te Ore Ore (near Masterton, about 100 kilometres northeast of Wellington), a man came forward to ask the tohunga a question that had been troubling many in the crowd: Which church should the Maori join? Paora did not reply immediately; instead, he asked the people to wait for a few days while he considered the matter. After pondering, fasting, and praying to Jehovah for enlightenment, Paora gathered his people and told them that they should continue to wait, because the right church for the Maori had not yet been brought to them. He then prophesied that his people would recognize the messengers of the true church by these signs: they would come from the direction of the rising sun; they would travel in pairs; they would speak to the Maori in their own language and would live among them rather than retreating to European-style homes; and when they prayed, they would raise their right arms. He also predicted that these messengers would teach that the Maori were some of “the lost sheep of the House of Israel,” and they would speak of a “sacred Church with a large wall surrounding it.” Paora Potangaroa claimed that the prophecy had come from “the Spirit of Jehovah,” and a scribe recorded it, along with an associated covenant for the people to remember the words.

The whare at Te Ore Ore, where Paora Potongaroa told his people to “taihoa”—wait, because the true messengers of God had not yet come to their village

Two years earlier, Tawhiao, king of the Waikato, had made a similar prediction to his followers. The true church, he said, would come in the future from ministers who would travel two by two. “They will not come to you and return to European accommodations but they will stay with you, talk with you, eat with you, and abide with you.” Even earlier, in 1845, a tohunga named Toaroa Pakahia also had prophesied that the messengers of salvation for the Maori people would come from the east and that they would raise their hands when they prayed. And back in 1830—the year the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints was organized in America—an elderly tohunga named Arama Toira had told his whanau that they should leave the Christian church that most of them had joined. “It is not the true church of the God of heaven,” he said. “The church you have joined is from the earth and not from heaven.” He went on to state that the “true form of worship” would come from the east, across the ocean. “You will hear of it coming to Poneke [Wellington],” he said, “and afterwards its representatives will come to Te Mahia” (the area where Arama Toira lived). “When this karakia [form of worship] is introduced among you, you will know it, for one shall stand and raise both hands to heaven.”

It’s likely that members of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints will feel a thrill of recognition when they hear about these prophecies by Maori tohunga, because it’s so easy to see parallels between their predictions and what the Maori must have observed when they finally encountered LDS missionaries in the 1880s. Unlike earlier Christian missionaries who had come to New Zealand from the west, sailing from Europe around the horn of Africa, the LDS missionaries from Utah sailed from California, crossing the Pacific from the east. The earliest Latter-day Saints to arrive in New Zealand, beginning in Wellington in 1854, initially focused their proselyting efforts on the Pakeha, but in 1881, a new mission president felt inspired to assign men to begin working among the Maori. Pairs of missionary “elders” were sent to live with the people, learn their language, eat their food, and sleep in their huts. And although the tradition of raising one’s arms or right hands during prayer has fallen out of practice among the Latter-day Saints except during certain priesthood ordinances, at the time it was common.

Missionary Matthew Cowley (in suit, white shirt and long thin tie) with his Maori brothers and sisters, circa 1916

More significant than these identifying details was the fact that, unlike other Christian preachers the Maori had heard, Mormon missionaries taught that the heavens are not closed, and that God continues to speak to his children through prophets in the same way that he spoke to them in Biblical times. With their own strong tradition of divine revelation through tohunga, the Maori were fully prepared to accept the idea that revelation continues, and that an American named Joseph Smith had received heavenly visitations and ongoing spiritual direction for re-establishing the Church of Jesus Christ on earth. The Maori liked what the Latter-day Saints taught about God: that he is our loving Father, not simply an angry, vengeful being who delights in punishing the wicked. They also appreciated the fact that the LDS missionaries not only affirmed that their ancestors were of the House of Israel, but could tell them exactly which tribe they descended from, and a little more about how those ancient Israelites had reached the islands of the South Pacific.

You may wonder how the LDS missionaries knew such things about the Maori. So did the German researcher who visited the Matthew Cowley Pacific Church History Centre in early March. The answer to this query, as Isabella explained to her, can be found in the Book of Mormon.

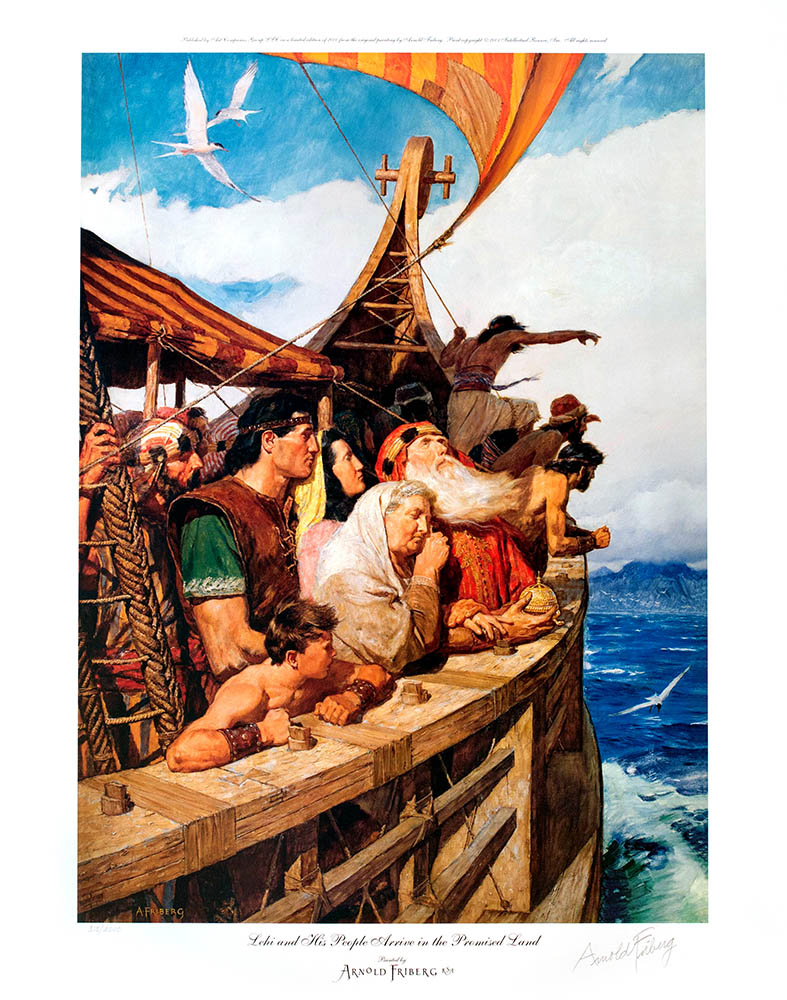

The book that Joseph Smith translated from the gold plates he found buried in upstate New York is a record of God’s dealings with people who lived somewhere in the Americas in antiquity. Moroni, the heavenly messenger who directed Joseph to the hill where the plates were hidden, was the last prophet of that ancient civilization, and the son of Mormon, the man who had been the principal compiler and editor of the book that bears his name. The record begins with an account of Lehi, a prophet who lived in Jerusalem at about the same time as Jeremiah, during the reign of King Zedekiah. About 600 BCE, the Lord told Lehi that Jerusalem was about to be destroyed, and instructed him to take his family and leave. So Lehi and his family, along with another family the Lord told them to invite, departed through the Arabah and into the wilderness near the Red Sea. After they had wandered along the edges of the Arabian Peninsula for several years, the Lord directed them to build a ship and sail to “a land of promise” that he had prepared for them. Joseph Smith identified that land as America, though he never specified where Lehi’s ship landed nor where he and his band eventually settled. As you can imagine, this has been a subject of speculation ever since the Book of Mormon was published in 1830.

Lehi and his family en route to the Promised Land

The introduction to the Book of Mormon states that Lehi’s descendants “are among the ancestors of the American Indians.” Older editions used to say that Lehi’s descendants “are the principal ancestors of the American Indians,” but the Church has officially backed away from that stance in recent years as its members have recognized that the nations described in the Book of Mormon could not have been as vast as they once believed. But even if one accepts that some native Americans are descendants of Lehi, and therefore descendants of the tribe of Manasseh (as Lehi’s genealogy specifies), how does one then make the leap to suggest—as LDS missionaries of the nineteenth century surely did—that the Maori of New Zealand also descended from Lehi and Manasseh?

Depiction of Hagoth leaving the Nephite civilization for parts unknown

The Book of Mormon records that “in the thirty and seventh year of the reign of the judges” (about 55 BCE), “it came to pass that Hagoth, he being an exceedingly curious man, therefore he went forth and built him an exceedingly large ship … and launched it forth into the west sea.… And behold, there were many of the Nephites who did enter therein and did sail forth with much provisions, and also many women and children; and they took their course northward.… And in the thirty and eighth year, this man built other ships. And the first ship did return, and many more people did enter into it; and they also took much provisions, and set out again to the land northward. And it came to pass that they were never heard of more. And we suppose that they were drowned in the depths of the sea. And it came to pass that one other ship also did sail forth; and whither she did go we know not” (Alma 63:4-8).

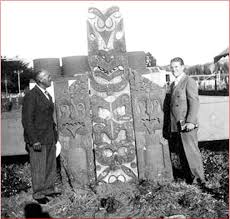

Tuati Whaanga and Elder Rulon Craven with a carving representing Hagoth, made for the Kahungunu Marae in Nuhaka, c. 1949

Early LDS missionaries taught that the “west sea” mentioned in the Book of Mormon was the Pacific, and that the people who sailed away on Hagoth’s ships were the ancestors of the Polynesians. The Maori of New Zealand were as fully prepared to accept this idea as they were to accept the concept of continuing revelation, because of their own national origin stories involving the waka hourua that came across the Pacific Ocean from a land called Hawaiki. To them, it did not seem at all far-fetched to think that an earlier, similar migration from America could have populated Hawaiki, nor that the ancestors of those people had originated in Jerusalem. Thus, the Book of Mormon came to be considered by many Maori as another record of their own heritage, and Lehi’s lineage was eagerly incorporated into the whakapapa (genealogies) of many Maori whanau.

Elder George Q. Cannon

While the current leadership of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints is as careful with its claims about the connection between Polynesians and the House of Israel as it is about the connection between native Americans and Lehi, earlier leaders were much less reticent. While serving a mission in the Sandwich Islands (Hawaii) in the 1850s, future apostle George Q. Cannon declared by revelation that the islanders had the blood of Israel running in their veins.

President Joseph F. Smith

Other Church authorities have supported Elder Cannon’s assertion. When President Joseph F. Smith welcomed a delegation of Maori Saints to Salt Lake City in June 1913, the Deseret Evening News reported that President Smith had told the visitors about something he had seen in Hawaii as a young missionary. While walking on the beach, he had noticed “great saw[n] timbers which had been driven from the mouth of the Columbia River or other points along the west coast of America, by sea currents and winds, directly to the shores of Hawaii, and it is very probable, he said, that Hagoth’s ship, which never returned, may have followed the currents likewise to the Pacific Islands.” He then stated: “[You] brethren and sisters from New Zealand, I want you to know that you are some of Hagoth’s people, and there is no pea [perhaps] about it.” A later Church president, David O. McKay, included this line in his 1958 dedicatory prayer for the New Zealand Temple: “We express gratitude that to these fertile Islands Thou didst guide descendants of Father Lehi, and hast enabled them to prosper.” Yet another Church president, Spencer W. Kimball, while speaking at a 1976 Church conference in Samoa, also affirmed that Pacific islanders—specifically including the Maori of New Zealand—were descended from Lehi and therefore part of scattered Israel.

President David O. McKay

President Spencer W. Kimball

But affirmation of a distinguished heritage was only part of what drew the Maori to The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. During the 1880s and ʼ90s, it was not unusual for entire villages to request baptism because the people believed that the LDS missionaries were true emissaries from God—not only because they fit the prophetic descriptions of their tohunga, but because the Mormon elders (whom the Maori called kaumatua, just as they did their own tribal elders) demonstrated real power: healing the sick, calming storms, and subduing their enemies. Unlike other Pakeha missionaries, the Latter-day Saints respected Maori customs, embraced their culture, and even helped them defend their land rights in court, thus winning the natives’ complete confidence. Most important, with their simple but profound faith, the Maori accepted the Book of Mormon as the word of God. They appreciated the clarity with which Book of Mormon prophets testified of the coming of Jesus Christ and explained his mission: to offer eternal salvation to all who would accept him. They loved the account of Christ’s appearance to the Nephites (one of the nations established by Lehi’s sons) after his resurrection, and were determined to live by his teachings.

A wooden panel carved by Taka Panere in 1969 hangs in the museum. It depicts the story of the Maori Saints, from their ancestors’ migration to New Zealand, through the prophecy of Paora Potangaroa and the arrival of the LDS missionaries, and culminating with a temple.

By 1898, Maori members accounted for about 90 percent of all Latter-day Saints in New Zealand. Part of the reason for their preponderance was that during the nineteenth century, probably 90 percent of New Zealand’s Pakeha converts emigrated to “Zion” (Utah), while the generally less-affluent Maori remained to “build up the Kingdom” here. By now, it’s probably impossible to determine what percentage of New Zealand’s 115,000-plus Church members are Maori and what percentage are Pakeha because there has been so much intermarriage among them during the past century; it seems that nearly every Latter-day Saint we have met here is a blend of both—which is how it should be. These days, Kiwi Saints are focused on “the work of the ministry [and] edifying the body of Christ: till [they] all come in the unity of the faith, and of the knowledge of the Son of God, … speaking the truth in love” (Ephesians 4:12-13, 15; emphasis added).

When their museum tour ended, our German visitors thanked the guide for explaining why the Book of Mormon and the doctrines of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints had resonated so strongly with the Maori, and for sharing the story of her own ancestors’ conversion to the restored gospel of Jesus Christ.

“Where can I buy a copy of the Book of Mormon?” asked the researcher. “I’d be very interested in reading it.”

Isabella told her that copies were available in the Church Distribution Centre downstairs—but later, while the woman and her companion were perusing our library, Isabella obtained a German translation of the Book of Mormon from the mission office in our building, wrote her testimony of its truthfulness on the flyleaf, and presented it to the couple as a gift. They were both pleased and grateful—and so was Isabella.

If you are interested in reading the Book of Mormon, you can access it online here.

Sources for the historical material and quotations in this post include the following:

“Alma 59–63,” Book of Mormon Teacher Resource Manual, The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, 2004, 191–93.

Britsch, R. Lanier. “Maori Traditions and the Mormons,” New Era, June 1981.

Britsch. Unto the Islands of the Sea: A History of the Latter-day Saints in the Pacific,” Deseret Book Company, Salt Lake City, Utah, 1986.

Church News, 10 May 1958.

Hunt, Brian W. Zion in New Zealand: A History of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints in New Zealand 1854-1977, Church College of New Zealand, Temple View, New Zealand, 1977.

Newton, Marjorie. Tiki and Temple: The Mormon Mission in New Zealand, 1854-1958, Greg Kofford Books, Salt Lake City, 2012.

Wonderful – thank you! I travelled through New Zealand when I performed for with the BYU International Folk Dance Ensemble. One of my favorite memories was when we performed at a local boys school. After our performance they performed the Haka. A room of about 300 young boys – 12-18 dressed in white shirts and uniforms filled the room with an indescribable electricity as their intense facial expressions and gestures brought me to tears. I imagined that this is what Helaman’s stripling warriors looked like: young, but fierce.

Thank you this is absolutely beautiful and makes me lonely for the Centre

Thanks for the endorsement. We are lonely not only for the Centre, but for you and the other volunteers, too!