After a weekend focused on family (among other things, we took our granddaughter Farrah and her sisters to see Frozen 2 to celebrate her fourth birthday, and enjoyed an adults-only dinner out with Hillary, Jake, Nat, and Emma), we went back to full-time missionary training at 9:00 a.m. on Monday 6 January. This week, however, our instruction did not take place at the Missionary Training Center in Provo, but at the offices of the Church History Department in Salt Lake City.

Millcreek Trax Station

Since we were staying at Hillary’s house in Salt Lake City again but were still several miles from downtown, we decided to join commuters taking the light-rail line into the center of the city. On the ride from the Millcreek Trax station to City Center, we knocked knees with a wide spectrum of humanity as we sped past the loading zones of several shopping centers and industrial parks: office personnel, students, factory workers, restaurant employees, some foreign-language speakers, and a few people who may have been homeless. Nearly everyone spent the trip staring into their phones.

Church History Library

We got off the train next to the City Creek Mall and walked a couple of blocks to the Church History Library on North Temple, directly across the street from the Church Office Building. There was a public reading room on the ground floor of the Library where one can see historic books and papers, including original manuscript pages and first-edition copies of the Book of Mormon. To get beyond the reading room, however, one has to be accompanied by an authorized Church History Department employee.

Church History Library Lobby

We were met at the front desk by Clint C, who focuses on the Pacific area in the Global Acquisitions Department and is one of the men who had interviewed us over lunch back in June; and by Bethany B, an acquisitions intern. After they got clearance to take us to their offices upstairs, the first thing they did was to lead us down a corridor lined with photos of the men who had served either as Church Historian or Director of the Church History Department since the Church was organized in 1830. (Yes, they were all men, although there was one photo of a woman who had served as an Assistant Director.) What we initially thought was going to be a deadly dull recitation of names and dates turned out to be a fascinating glimpse into the politics of recording history within The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints.

The charge of the Church History Department

Maintaining accurate, detailed records has always been a vital part of our religion. On 6 April 1830, the day the Church was organized, Joseph Smith received a revelation in which the Lord commanded: “Behold, there shall be a record kept among you” (D&C 21:1). Oliver Cowdery, who had been Joseph’s chief scribe during the translation of the Book of Mormon, also kept historical records for the newly founded Church, but the first official Church Historian was John Whitmer, who was called by revelation in 1831 (see D&C 47). The Lord reiterated his instruction to keep a careful history many times. “Continue in writing and making a history of all the important things … concerning my church,” he said (D&C 69:3). “Let all the records be had in order, that they may be put in the archives of my temple, to be held in remembrance from generation to generation, saith the Lord of Hosts” (D&C 127:9). Latter-day Saints today still understand that record-keeping is important not only because “the dead [will be] judged out of those things which [are] written in the books” (Revelation 20:12), but also because written records allow us to preserve religious doctrine and other vital aspects of our heritage for posterity.

Leonard Arrington, the first academic to head the Church History Department

Over the years, however, there have been conflicts among the human beings assigned to keep those accurate, detailed records about how the history should be written. In one camp are those who believe that the only history worth recording is the uplifting and faith-promoting; in the other camp are those who believe that recorded history should include the whole truth, no matter how distasteful. As Clint and Bethany walked us through the photo gallery, they described how the Office of the Church Historian—which was always directed by a general ecclesiastical authority who may or may not have had any relevant academic training—morphed into the Church History Department. This major change came about in 1972, when Leonard Arrington, a professional historian, became the first non-ecclesiastical authority to assume directorship. Arrington’s tenure was fraught with strife as his battalion of truth-tellers ran afoul of the faith-promoters in the upper echelons of Church leadership. (Michael and Nancy remember this era vividly because it occurred during the years of our graduate schooling and young adulthood, and we knew some of the people who were directly involved in the conflicts.) Within a decade, Arrington and his academically oriented assistants had been exiled to Brigham Young University, and the Church’s History Department was quietly retaken by the faith-promoters. Thus, for many years we got Church publications that, for example, contained biographies of Joseph Smith and Brigham Young with no mention that either of them had engaged in polygamy. In recent years, however—possibly thanks to the fact that the Internet prevents any historical secrets from remaining hidden for long—the pendulum of the Church History Department has begun to swing back toward the recording of the whole, messy truth. Both ecclesiastical leaders and academic researchers now seem committed to recording our collective history as accurately and transparently as possible, and making it more widely accessible.

After their review of the history of the History Department, Clint and Bethany led us to a conference room where they explained more about the Department’s current functions. The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints operates several Records Preservation Centers around the world, where qualified workers gather and conserve original Church historical documents for each region in which the Church is established. In the past, such records were sent to Church headquarters in Salt Lake City for safekeeping; but recently Church leaders have acknowledged that historic documents belong to the people who produced them and to whom they mean the most, and thus should remain in their countries of origin. The new RPCs offer a controlled environment where important records can be safely stored, and where they can be digitized and properly cataloged by trained employees and volunteers. Digital copies are then sent to the main Church History Library.

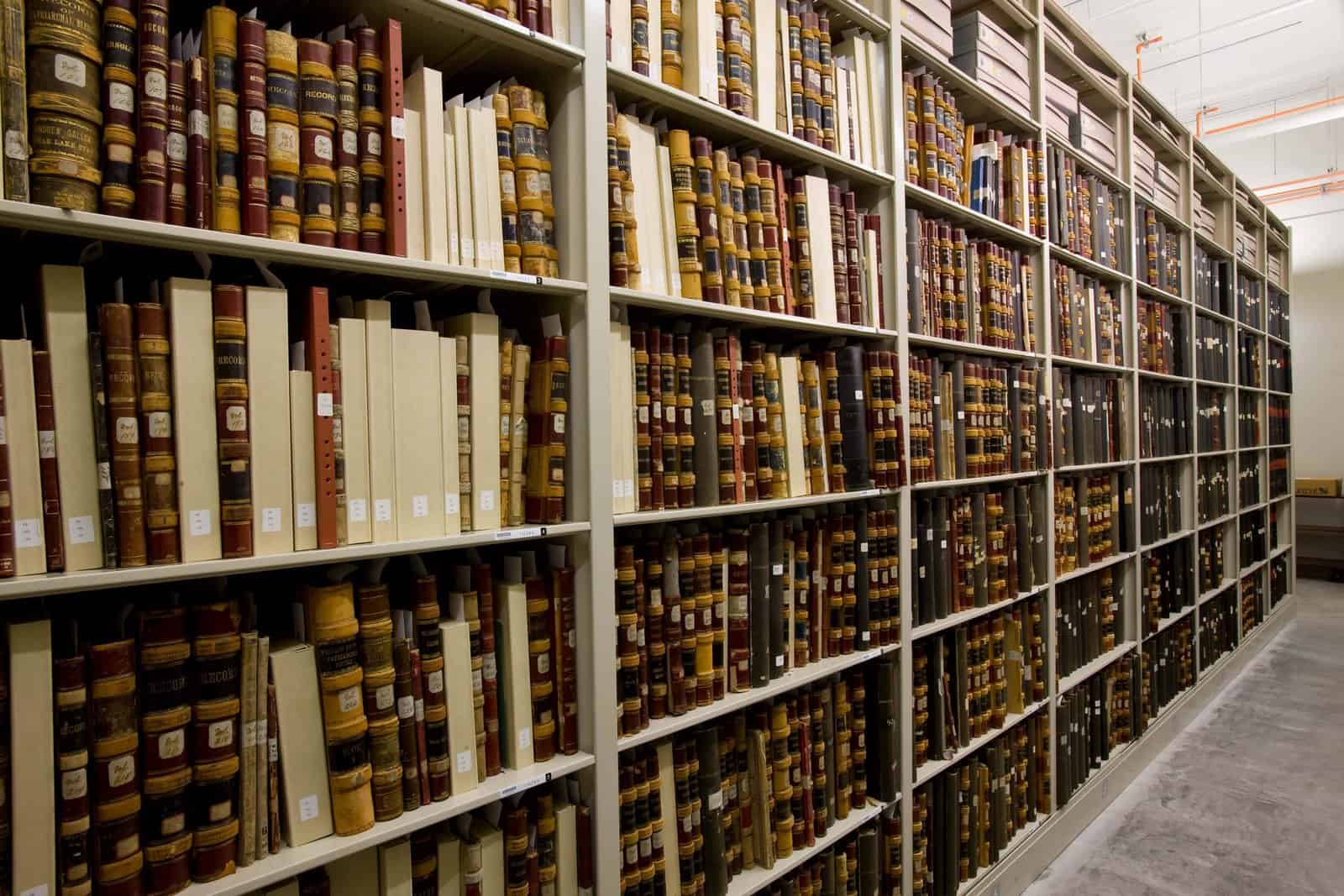

Church History Library Archives

Clint and Bethany proceeded to give us a tour of Salt Lake City’s RPC. Before we entered the “cold room” where the most fragile records are kept, we donned down jackets from a closet just outside the heavy door, but still shivered as we stepped through a second door on the other side of an air-lock chamber that helps maintain the temperature at –5°F. We walked past shelf after shelf of old newspapers, leather-bound books, and other sensitive materials protected from light and humidity by thick walls deep within the building. In one section we noticed what may have been a complete set of copies of the original Woman’s Exponent, a periodical published from 1872-1914 by the plucky Latter-day Saint women who also were early proponents of women’s suffrage. Their work inspired “Mormon feminist housewives” of a later generation to begin publishing Exponent II in 1974. (Nancy has been an occasional writer and guest editor for this quarterly.)

Taking us back to the warmth of the conference room, Clint and Bethany explained that the Matthew Cowley Pacific Church History Centre in Hamilton, New Zealand, where we had been assigned to work, contains a much smaller Records Preservation Center, but it also contains a museum—the only Church History Museum outside Salt Lake City. The main reason a museum was established in New Zealand is that a remarkable woman named Rangi Parker has spent the last few decades amassing thousands of photos, journals, newspaper clippings, taped oral histories, and other artifacts related to the establishment and growth of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints in the South Pacific. When her collection threatened to overrun their home, Rangi and Vic, her incredibly supportive husband, moved it to the former administration building of the Church College of New Zealand, which closed in 2009. In 2014, the Church decided to demolish most of CCNZ’s abandoned buildings, but the former library was renovated and repurposed as a museum and Records Preservation Center, with the materials Rangi had collected as the foundation of its holdings. Our task, as we were beginning to understand it, will be to make sure that as items from the collection are digitized (which is someone else’s job), they are properly cataloged so that they can be more readily accessible to historical researchers, as well as to descendants of the early missionaries and Church members who appear in the old photos.

Blue Lemon in City Creek

By noon all of us were ready to break for lunch, so we walked across Temple Square to the Blue Lemon. Here we learned, when Clint carefully removed the melted cheese from the French onion soup he had ordered, that he and his family do not eat dairy products—a circumstance we found intriguing because his three children are all adopted and come from three different ethnic groups.

The first part of our afternoon was spent learning about Webcat, the software the Church History Department uses to keep track of its acquisitions. Nancy tried valiantly to not zone out when the conversation became too technical, and was relieved when Clint announced that we were about to go across the street for a tour of the Church’s 21,000-seat Conference Center. We have attended a few sessions of General Conference as well as some concerts in the Conference Center, and we had taken a tour of the building shortly after it opened in 2000, but today’s tour was somewhat different. Because the Salt Lake Temple and Visitors Centers are now closed for extensive renovation, visitors to Temple Square are being directed to the Conference Center, where new exhibits are on display. One new attraction was a video that showed how the temple’s foundation will be upgraded to make it less susceptible to earthquake damage, and how the rest of Temple Square will be altered to improve the visitor experience. We also looked at a 32:1 scale model of the temple that shows in cutaway its original layout and furnishings, although we had a little trouble seeing all the details because of two workmen who were standing within the model’s enclosure, repairing its electrical system. The temple itself will be out of commission for four years, and already its closure has altered both car and foot traffic in downtown Salt Lake. Today we noticed a marked decrease in the number of people walking along the sidewalks as we went to lunch, and there were actually many empty parking spaces around Temple Square—an unusual sight, indeed!

Church History Library Reading Room Stacks

Our first day of Church History Department training ended with a closer inspection of the treasures on display in the public reading room. Clint explained that the Book of Mormon manuscript pages and first-edition books are swapped out periodically so no one item is exposed even to the carefully controlled light of the display cases for too long. The same will be true of items in the New Zealand museum’s collection, although caring for the artifacts in the exhibits will not be our direct responsibility; the MCPCHC has a trained conservator on staff.

City Creek Shopping Center

When we left the Library about 4:30, we decided to walk over to the City Creek Center to make arrangements at the AT&T store to discontinue our phone service on 10 January, after we leave the U.S. That was a wasted effort because the store clerk told us that we needed to do it online, but going to City Creek Center wasn’t a waste because the Clark’s store was running a clearance sale and Michael was able to find exactly the type of black dress shoes he had been looking for at a good discount. We walked around the mall for a few minutes before the train arrived to take us back to Millcreek.

Church History Museum

On Tuesday, we took the train downtown again but this time headed to the Church History Museum, also located on North Temple but on the opposite side of Temple Square from the Library. There we were met by Tiffany B, the education curator, who would be our trainer for the day. Tiffany immediately impressed us as someone we would get along well with. The first things we noticed were the personal mementos on the wall system behind her desk: photos, small plaques, and magnets representing people and places that obviously were significant to her, aesthetically arranged in an unusually pleasing way. The next thing we noticed was that she had prepared a very well-organized notebook for each of us, which included not only an agenda for the day but also a photographic tour of every exhibit in the Matthew Cowley Pacific Church History Centre’s museum. Tiffany and four other Church History Museum staff members with whom we will be working remotely over the next two years had visited the museum in New Zealand in September, so they had direct knowledge of the people we will be working with there and the challenges we will face as we assist in operating the museum. But the first item on Tiffany’s agenda for us that morning was a behind-the-scenes tour of Salt Lake’s Church History Museum.

We had visited the museum several times before and were familiar with most of the permanent exhibits, but Tiffany drew our attention to how items are displayed, and why curators and designers chose to display them in those particular ways. She described challenges they had to overcome, such as lighting a historic costume in such a way that its details could be seen without making the light bright enough to damage the fabric, or keeping the museum fresh for return visitors while retaining key artifacts and information for first-timers. To help us better understand how to create exhibits that engage visitors effectively, she pointed out changes that had been made to some original displays after curators learned what worked and what didn’t. In addition, she gave us a sneak peek at an exhibit that is scheduled to open in February, called “Temples Dot the Earth: Building the House of the Lord.” It’s geared toward children, with lots of interactive displays to help them understand how and why temples are constructed.

Next on Tiffany’s agenda was a meeting with the five CHM staff members who comprise the MCPCHC’s advisory team: conservators Scott and Carrie; Tyler, who specializes in digital conservation; Berk, the finance guy; and Tiffany, the curator. As they explained what they do and how they work together, we gained an even greater appreciation for what it takes to preserve valuable historical artifacts without simply packing them away, never to be seen in public again. We had visited the document storage facility at the Church History Library, but now Michael was curious about where large artifacts such as antique furniture and factory equipment were stored. “I’m picturing that cavernous warehouse at the end of Raiders of the Lost Ark, with row after row of identical wooden crates,” he said.

Everyone laughed. “Actually, you’re not too far off,” said Scott. “We used to keep big stuff in a back room here at the museum, but we ran out of space, and it wasn’t very safe, anyway. So now we have a climate-controlled vault in another location—and yes, it’s full of those Indiana Jones-style crates.”

Market Street Grill

Tiffany had planned to take us out to lunch after the team meeting, but we had already made arrangements to meet our friend Cathy S, who lives up the street from Temple Square, at a nearby restaurant. However, spending the morning with Tiffany had been such a delight that we were loath to leave her behind, so invited her to join us; we were sure Cathy would be pleased to make her acquaintance, and there was no question that Tiffany would be glad to have met Cathy. As one of the first African-Americans to join the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints in Chicago during the 1970s, Cathy might be considered a living historical treasure. In the decades since she was baptized, Church leaders have sought Cathy’s help in reaching out not only to the African-American community, but also to leaders of several African nations. She has dozens of fascinating stories to tell about her experiences as one of the Church’s foremost black ambassadors—and about what it’s like to have the ear of some of the Church’s most influential people. As we anticipated, Tiffany and Cathy were happy to meet each other, and we were happy to have brought them together over the great seafood at the Market Street Grill.

It wasn’t easy to end our lunchtime conversation by 1:15, but Tiffany had scheduled another meeting for us, this time with Joe M, the CHM’s technical support specialist. Michael will need to communicate directly with him for advice when the MCPCHC’s interactive displays need upgrades or get glitchy. When we entered the conference room, we found Berk there with a sheaf of papers spread out across the table in front of him. Tiffany apologized for the interruption, but explained that she had reserved the room for our meeting with Joe. “You’re welcome to stay if you don’t mind listening to us talk,” she told him. “And feel free to join the conversation, because you may be able to add something helpful.” So Berk stayed—and ended up saying a lot more than Joe did. That wasn’t necessarily a bad thing because Joe had prepared a printed cheat sheet for Michael and didn’t have much more to say once they had skimmed through it, but we learned a lot from Berk about what it takes to get funding for museum upgrades and approval for new exhibits and equipment. (Office politics are office politics, even within the Church.)

Beehive House

For the remainder of the afternoon, Tiffany accompanied us on a private tour of the Beehive House, which functioned as Brigham Young’s offices while he was the territorial governor of Utah as well as president of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, and as the residence of his sprawling family with several polygamous wives. This was not our first visit to the Beehive House, which is located a block from Temple Square, but it was our first visit in more than forty years. In case you were wondering, the Beehive House was so named because Brigham Young chose to use the beehive as a decorative motif throughout the building, hoping his people would emulate the bees’ example of industriousness and cooperation. Our guide was (according to Tiffany) one of the best. She shared some interesting stories that were new to us, as well as reviewing familiar information and answering our questions.

With Tiffany in front of the Beehive House

When the tour was over, we reluctantly said goodbye to Tiffany and walked over to the Joseph Smith Memorial Building to meet Jeff and Kara, friends from our days in Delaware who also have been called to a mission in New Zealand. They will be serving as public communications specialists in the Pacific Area offices in Auckland, just an hour and a half away from us. Kara has an advantage over other Americans called to serve in New Zealand: she doesn’t need a visa because she was born in Hamilton while her father served as the master plumber during the construction of the Church College of New Zealand and the Hamilton New Zealand Temple. Jeff was still waiting for his visa, but he should be okay because they are not scheduled to report for duty until April.

Red Iguana

As you may imagine, the four of us had lots to discuss over dinner at the Red Iguana. (We recommend anything on the menu that includes mole sauce.)

On Wednesday 8 January Nancy woke up with the kind of raw throat that signals the start of a cold, but only briefly considered staying at home from her last day of training. So, armed with a purse full of tissues, throat lozenges, zinc tablets, and hand sanitizer, she accompanied Michael back to the Church History Library. Clint was unexpectedly tied up in a meeting with someone more important than we were, so Bethany took charge of reviewing how Webcat (the acquisitions management system) worked and requesting authorization for us to use it, and then guiding us through a short tour of the Church Office Building (which Church employees refer to as “the COB”). Tyler, the digital conservationist from the CHM, came with us. We now feel like true insiders because we reached the COB by navigating past some underground CHD storage vaults and then through the legendary secure tunnels underneath Temple Square. Bethany took us up to the observation deck on the 26th floor of the COB, but it was too cloudy to see very far and too blustery to stay very long; however, we enjoyed seeing the original artworks on display in the lobby and adjacent corridors.

Garden Restaurant

From there, we crossed the street and went to the Joseph Smith Memorial Building for lunch in the Garden Restaurant. From that tenth-floor vantage point, we could see exactly how far the demolition of the South Visitors Center at Temple Square had progressed.

After a little more review of Webcat, Bethany pronounced our training complete and accompanied us back to the ground floor of the Library so she could sign us out. We still had a lot of questions about the tasks ahead of us, but we were ready to get to New Zealand and get on with our work.

A wintry day on Temple Square

That evening we walked back to the Church History Museum, where Nat and Emma met us to view “Sisters for Suffrage,” the current special exhibit honoring the Utah women who lobbied for female enfranchisement and in 1870 became the first women in America to legally vote. We were gratified to see the museum’s frank presentation of the role polygamy played in the suffrage movement—evidence that the Church of Jesus Christ has indeed become more open about troubling aspects of its past. During the 1860s, anti-polygamists across America thought that if they promoted voting rights for Utah women, “oppressed” plural wives would rise up and put an end to polygamy. Instead, Mormon women vigorously defended the practice and thus were disenfranchised again by the U.S. Congress from 1879 until after the Church officially disavowed polygamy in 1890. Perhaps in another hundred years, the Church History Museum will mount an exhibit honoring the dedicated founders of Mormon Women for Ethical Government who helped save American democracy in the early twenty-first century.

We said goodbye to Nat and Emma after dinner at the Nordstrom Grill and headed back to Hillary and Jake’s house to do our last loads of laundry before leaving the U.S. Fortunately, we did not have to be at the airport until about 12:30 p.m. on Thursday 9 January, so we had time to hug our grandchildren before they left for school that morning and then to pack, weigh, and repack our bags to make sure that none of them would exceed the fifty-pound limit. We had been given conflicting information regarding our luggage allowance from the Church Travel Department, who said that each of us would be allowed to check two bags free of charge, and United Airlines, who told us that we could have only one free bag each, and that there would be a $100 charge for each additional bag. Moreover, United said we would be charged another $100 for any bag weighing over fifty pounds. At that point, there was no getting around the fact that each of us was going to have to check two big bags, so we did our best to distribute the weight to avoid exceeding the per-bag limit, and hoped that the Church Travel Department’s information was more accurate than United’s.

It wasn’t.

However, we were blessed at the United check-in desk with a sympathetic agent who said that although he couldn’t waive the second-bag fees, he could check one of our extra bags as “skis,” for which there was no charge. We thanked him profusely and proceeded onto our flight to San Francisco without further ado. Ironically, our carry-ons, though within size and weight limits, did not fit in the overhead compartments, so they had to be “valet checked” and picked up at the gate when we arrived.

Air New Zealand Aircraft

By 8:30 p.m. we were aboard an Air New Zealand flight from San Francisco to Auckland. Because the Church had purchased our tickets, we couldn’t take advantage of any comfort upgrades, but our seats were probably the best we could hope for in economy class: Michael had reserved the last available bulkhead seat, while Nancy (whose legs are not as long) was content to sit in the next-best available seat: on the aisle, on the opposite side of the plane. Neither of us minded being separated (although one flight attendant was concerned that our relationship might suffer as a consequence) because once the dinner service was over, we both managed to fall asleep and stay asleep for about five hours—our first missionary miracle!

Both of us happened to be seated next to Kiwis returning from spending the holidays with relatives in England, and we were grateful that we had not had to cross both the Atlantic and all of North America before beginning our flight across the Pacific that evening, as they had. They would spend a total of twenty-four hours en route; our trip took about fourteen hours, during which Friday 10 January vanished into the thin air over the Pacific Ocean.

Nancy, Thank you so much for posting these updates. I am enjoying your writing and found the behind-the-scenes glances fascinating.