Raspberry and Cream Cheese Stuffed French Toast

This morning was the coolest and most blustery that we have had so far on the trip—too chilly to eat breakfast on the open veranda, despite the fleece blankets offered on the back of each chair and the luscious hot chocolate, which many of us have become accustomed to ordering. (We wonder if, when the quartermaster is debriefed about exactly what was consumed on this voyage, he or she will report an unusual spike in the consumption of hot chocolate, thanks to the ten percent of the Star Breeze’s current passengers who drink it instead of coffee or tea because they are LDS.) Had there not been so many other guests waiting for indoor seating this morning, we might have lingered longer over our French toast, which both of us ordered because it came stuffed with red raspberry cream cheese and was as delicious as it sounds. We had to get up and leave our table anyway so we could collect some buffet items for another bag lunch to take on today’s tour.

We had more than an hour after breakfast to do laundry, read, and write because we had not yet docked, and weren’t scheduled to meet our guide for a tour of Tallinn until 11:15. We were advised not to dawdle too long, however, because it would likely take us at least twenty minutes to walk from our ship to the bus parking lot clear on the other side of the cruise ship port. The little Star Breeze has been relegated to a berth at the far end of the pier, muscled aside by five gigantic cruise ships that collectively are carrying at least 16,000 passengers. A sixth such leviathan docked this afternoon while we were in town.

The cruise ship in the foreground is about 20 times the size of the Star Breeze, carrying 4500 passengers and a crew of 1500

The V.I. Lenin Palace of Culture and Sport, erected for the 1980 Olympics and now abandoned. Look for it in a scene in Christopher Nolan’s “Tenet”

No wonder, then, that Tallinn, with a resident population of about 400,000, seemed absolutely overrun by outsiders today. In addition to the tourists, director Christopher Nolan (Memento, The Dark Knight, Inception, and other mind-bogglers) and his crew are here this week, shooting scenes for a film called Tenet. The project, an international spy thriller starring Robert Pattinson and John David Washington, is rumored to have a budget of $225 million (astronomical even by Hollywood standards), but few other details have leaked. What we can tell you is that the movie will include a scene in which a horde of emergency vehicles bearing the logo of some Ukrainian entity will swarm into the remains of the stadium the Soviets built for the 1980 Moscow Olympics (in which Tallinn hosted the sailing events). We can also tell you that the film’s costume designer (who passed our bus this morning) travels in a black Lexus sedan with signs that say “Costume Designer” taped to the windows. According to our guide, filming is going to shut down Estonia’s main Pärnu Highway for the entire month of July, and the locals are not happy about that. We are glad that it’s still June.

Sergei, our Estonian guide

Typical 1920s wooden house

Sergei, whom we met in the bus parking lot at 11:15, wisely directed our driver beyond Tallinn’s walled medieval center, hoping that by the time we returned to Vanalinn (Old Town) the majority of passengers from other cruise ships would have moved on. As the driver battled traffic across the city, our guide pointed out examples of typical Estonian architectural styles, as well as giving us a brief history of his country. (Sergei told us that although his father was a Russian naval officer who came to Estonia in the 1970s so he and his wife could work in a factory, Sergei considers himself a native Estonian because he was born and raised here.) Because Estonia had been the last country in Europe to convert to Christianity, it became the main destination for the Northern Crusades during the thirteenth century. Danish and German crusaders established a feudal society here, “basically enslaving the locals” (as Sergei put it) and suppressing the native language and culture. Since then, countless wars have been waged for control of this strategic territory on the Baltic Sea; Denmark, Germany, Poland, Sweden, and Russia all had turns ruling the area.

2000s modern Tallink Hotel

Although Russia was nominally in charge of Estonia from the time of Peter the Great (1710) until 1917, the country’s economic, legal, religious, and educational systems retained the influence of the German-speaking nobility who had established those systems in the Middle Ages. Ironically, that same German-speaking elite, motivated by Enlightenment ideals of liberty, equality, and brotherhood, ended the feudal system in 1816 and encouraged the freed serfs to revive their native language and traditions. Estonian—a tongue related only to Finnish, Hungarian, and the languages of a few tribes in the Ural Mountains—began to be used in schools, churches, and newspapers for the first time, and a distinct national identity began to develop. Choral singing in the Estonian language also became an important addition to the country’s cultural heritage during the nineteenth century.

An example of 1930s “functional” style architecture

In 1918, Estonians—like the Finns— took advantage of disarray in the Russian government and declared independence, but although they didn’t have to suffer a civil war as the Finns did, Estonia’s road to full autonomy was longer and bumpier than Finland’s. The country joined the League of Nations in 1922, but due to its strategic location, neither Russia nor Germany would leave it alone. The Red Army invaded in 1940 and incorporated Estonia into the Soviet Union; a year later, the Nazis took control. By the end of 1944, a decimated Estonia had been retaken by the Red Army and would remain under the thumb of the Soviets until the last decade of the twentieth century. Once again, the Estonian language and native culture were suppressed.

National Theatre and Opera House, opened in 1913

But the yearning for a free Estonian state never died. Beginning in 1980, a series of music festivals where participants joined in singing patriotic songs were held across the country. Riding this new wave of nationalist fervor, Estonia’s Supreme Soviet (legislature) issued a declaration of national sovereignty and reinstated Estonian as the republic’s official language. Mikhail Gorbachev’s perestroika (restructuring) and glasnost (openness) policies—attempts to head off grassroots uprisings within the Soviet Union—further raised the hopes of Baltic nationalists, who revived their “Singing Revolution.” In 1989, two million demonstrators formed a human chain across the Baltic States from Tallinn to Vilnius, Lithuania, standing for independence. But hardliners in Moscow responded by stepping up their efforts to subdue such insubordination. When the Soviet military attempted to crush the Baltic independence movement in 1990, Estonians responded by blocking the paratroopers who tried to seize Tallinn’s TV tower. In 1991, after it became obvious to everyone that the Soviet empire was imploding, the European Community recognized Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania as independent states. The U.S. and the Russian Federation (which had separated itself from the U.S.S.R. only a few months earlier) soon followed suit, although Russia did not withdraw its troops from the Baltics for a few more years. Latvia and Lithuania lost a few dozen citizens during the Soviet invasion in 1990, but Estonia managed to achieve independence without bloodshed.

The 2019 International Choir Festival at Tallinn’s Lauluväljak

As choral singers ourselves, we are inspired by the Estonians’ devotion to choral music and the ways they have used singing not only to enhance their culture but to unify their nation. Estonian song festivals began in 1869 and have since expanded to include choral groups from around the world. In April of this year, the sixteenth International Choir Festival, held in Tallinn’s Lauluväljak (song festival grounds) every five years, took place. We’re sorry we missed it. Sergei pointed out Lauluväljak as we passed it on the highway this morning. The outdoor venue has room for 100,000 spectators, and the huge acoustic shell can accommodate 15,000 performers—absolutely astounding numbers to those of us who struggle to entice audiences and recruit singers for our own choral organizations. Few people may understand the Estonian language, but the people here have learned to use music effectively to speak directly to everyone’s hearts.

Maarjamäe History Center

A red carpet leads visitors to the Estonian Film Museum

Just beyond Lauluväljak is the Maarjamäe History Center. The museum occupies the house and grounds of the Maarjamäe Palace, which was built in the latter part of the nineteenth century as the summer residence of a count from Saint Petersburg. In 1933, the property was transformed into an elegant hotel and restaurant, but in 1937 it was purchased by the government and used as an aviation academy until the school outgrew the site. In 1987, the Maarjamäe complex reopened as part of the Estonian History Museum.

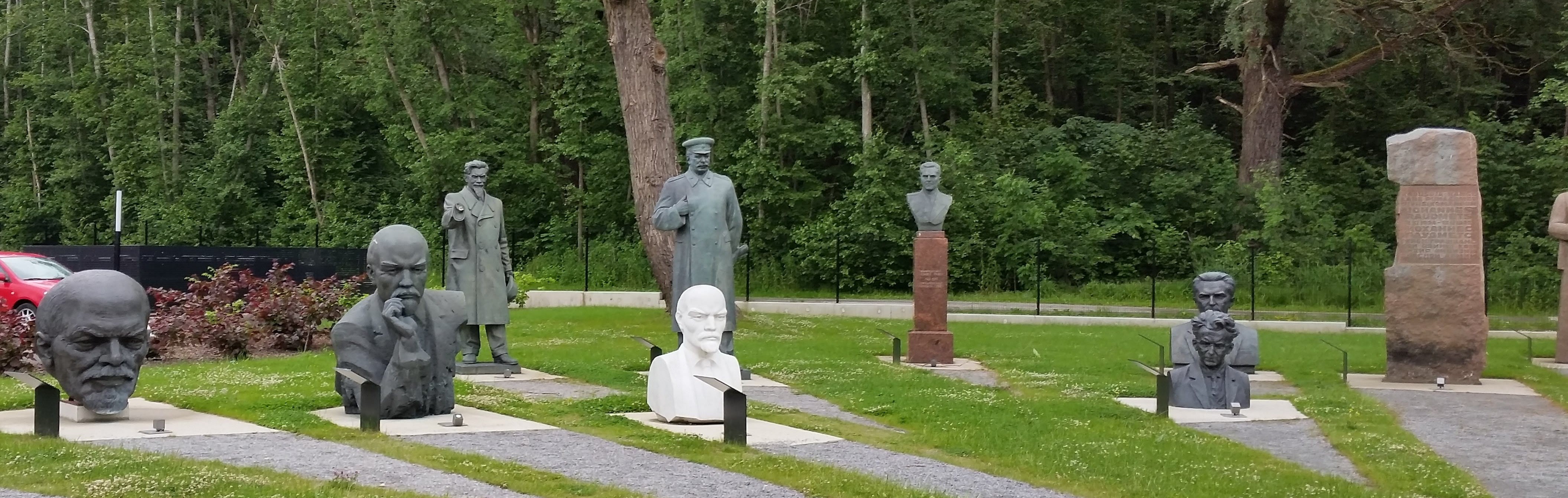

Graveyard of Soviet-era statues

Kersti Kaljulaid, Estonia’s current president, is also its youngest; she was 46 when she was elected in 2016

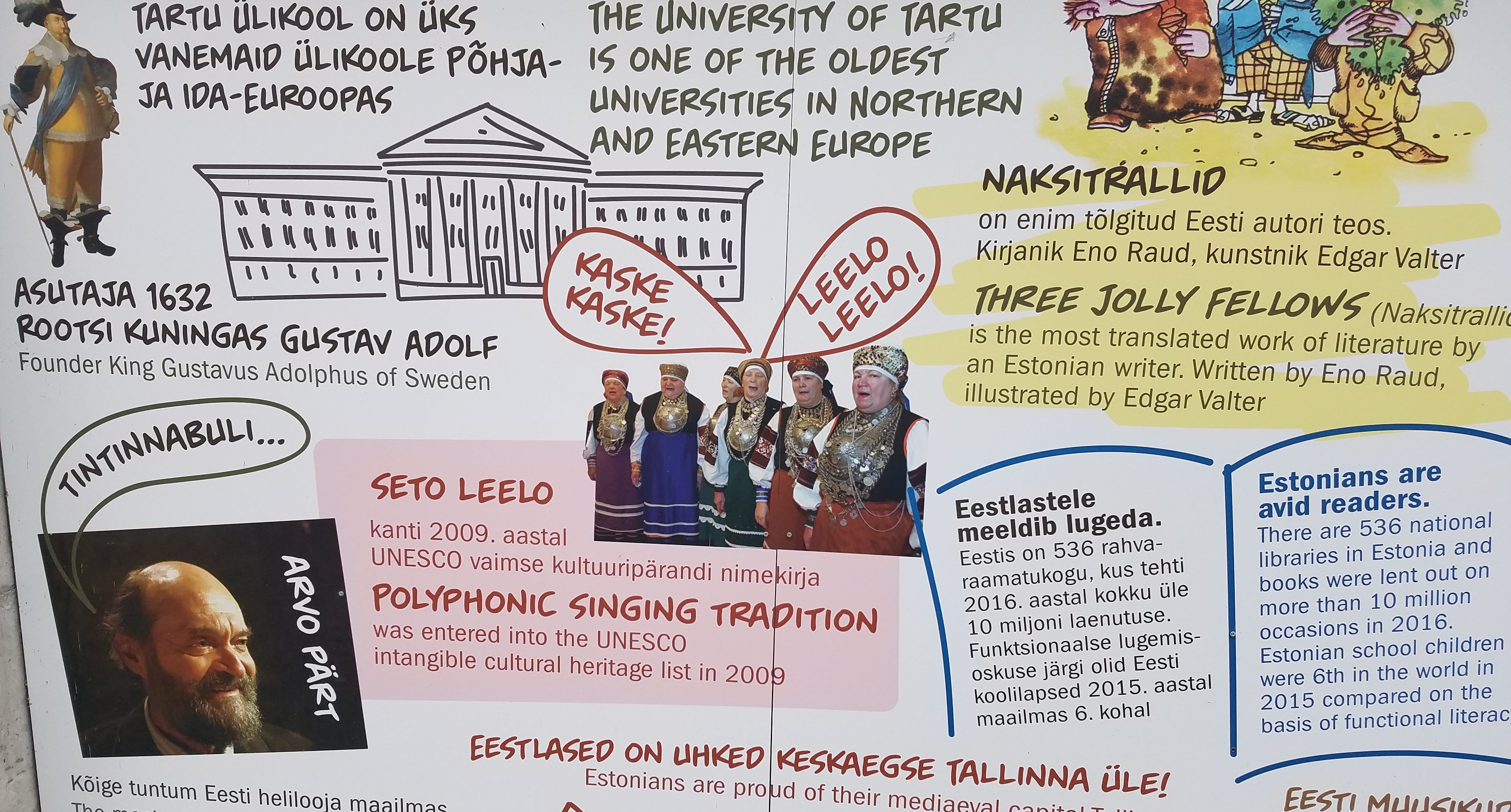

It includes the Estonian Film Museum and space for special exhibitions, as well as an outdoor “graveyard” for Soviet-era statues and memorials that have been removed from other areas of the country. Another feature we really enjoyed was a whimsical outdoor display introducing visitors to Estonian culture through fun facts. (Did you know that more meteorites have fallen on Estonia than on any other country in the world? Or that the Estonian national epic is about Kalevipoeg, a hero who throws rocks and talks to hedgehogs?)

Wall of fun facts about Estonia

Russalka Monument

Along the same stretch of the Pirita Highway as the song festival venue and the history center are three significant large memorials. The first monument we stopped to see was the oldest, raised in memory of sailors who lost their lives when the Russalka, a Russian battleship, sank in the Gulf of Finland in 1893. The name of the ship is Estonian for mermaid, but the figure on the monument is an angel lifting a cross toward the place where the ship went down.

Soviet War Memorial

The second monument, the Soviet War Memorial, was erected in 1960 and is more controversial. At the center is a 35-meter stone obelisk commemorating a World War I sea battle in which the Soviet Navy broke through a German blockade, but it is surrounded by concrete slabs forming an abstract square that honors Soviet heroism during World War II. During the Communist era the site served as a platform for state ceremonies and the starting place for military parades, and thus has negative associations for Estonians. Today the obelisk and concrete installations are crumbling, and an “eternal flame” on the square no longer burns. Since most Estonians are not keen on spending a million euros to restore and maintain a monument that brings back painful memories, there is talk of tearing the whole thing down.

Memorial to the Victims of Estonian Communism, 1940-1991

The third monument, the Memorial to the Victims of Estonian Communism, opened just last year. Two walls of polished black stone form a tribute to the 75,000 people—about one-fifth of Estonia’s population—who were killed, imprisoned, or deported during the Soviet occupation from 1940 to 1991.

The juxtaposing of these three monuments is emblematic of the difficult balancing act that Estonians had to perform throughout the twentieth century. Sergei told us that they don’t like to talk about the terrible World Wars, which not only ravaged their land, but also forced them into alternating periods of conflict and complicity with both Germany and Russia, their long-time oppressors. During World War II, kids playing the equivalent of “Cowboys and Indians” always called the bad guys “Nazis,” but their parents weren’t exactly rooting for the Russians, either. While Estonians today may not be proud that they allowed Communism to dominate for so long, they don’t shy away from facing the realities of their past, and they are willing to recognize the sincere efforts and sacrifices of former enemies as well as current allies.

The marina where Olympic sailing events were held in 1980

Convent of St. Bridget

The rain that had been threatening all morning began to fall in earnest as we reboarded the bus, where we ate our lunch. Before turning back toward the city center, we followed the Pirita Highway a little farther up the coast to see the marina that had been the venue for sailing events during the 1980 Moscow Olympics, as well as the nearby ruins of the Convent of St. Bridget, Europe’s patron saint. The wife of a Swedish courtier, Bridget was inspired by lifelong visions of Christ to use her wealth and position for charitable work. The Catholic convent in Pirita, about ten kilometers from central Tallinn, was established about thirty years after Bridget’s death in 1373 and was home to both nuns and monks until it was sacked and burned by Ivan the Terrible in 1575. It now serves as a picturesque concert venue.

Tallinn University

Back in town, Sergei pointed out Tallinn University, which had opened as a teachers’ college in 1910. In 2005 it merged with several other colleges and research institutes to form one central university, which now has around 8,000 degree-seeking students from Estonia as well as other countries. Estonians are among the most highly educated people in the world, with a literacy level of 99.8 percent. The country has 536 national libraries, lending out more than 10 million books a year to just over 1.5 million inhabitants.

Hotel Palace

The Hotel Palace was Tallinn’s most fashionable place to stay after it opened in 1937. It was completely renovated in 1988 and again in 2004 to meet the highest European standards of elegance and service.

When we reached Vanalinn (Old Town) a little after 1 p.m., the rain had diminished to intermittent showers; by mid afternoon the sun had broken through. The bus dropped us off in the upper town, just below Toompea Castle.

Toompea Castle, home of the Riigikogu, Estonia’s parliament

The original fortification on Toompea Hill, a natural promontory overlooking the sea, is thought to have been established in the ninth century. In 1219, Danish crusader Valdemar II (whose name Nancy initially misheard as “Voldemort”) captured the stronghold and claimed the settlement for Denmark and (ostensibly) for Christ. The castle constructed here over the next century became known as Taanilinnus, Estonian for “castle of the Danes,” from which the name Tallinn probably was derived. During the sixteenth century, as the power of the crusaders’ religious orders waned, administration of the castle was taken over by the Swedes, and then by the Russians. In the 1700s, Russian governors added a baroque-style palace to the complex. This building now houses the Riigikogu, Estonia’s Parliament.

Alexander Nevsky Cathedral

Across the street from the castle is the Alexander Nevsky Cathedral, Estonia’s largest Russian Orthodox church. Built at the end of the nineteenth century when Estonia was part of the Russian Empire, it is dedicated to a sainted thirteenth-century Russian prince who won a decisive battle against Livonian Order forces that included native Estonians, fought on the frozen surface of Lake Peipus, which largely forms the boundary between Estonia and Russia. Understandably, Estonian nationalists regarded the church as a symbol of Russian oppression. During the country’s brief period of independence in the 1920s they decided to demolish it, but funds were never secured to proceed with that plan. For the next seventy years the church was left to decline (like many religious edifices under the Soviets) but Estonians must have had a change of heart about razing it since 1991, because the cathedral now has been carefully restored and seems to have become a source of local pride.

St. Mary’s Cathedral

Up the street is the Toomkirik (Dome Church), also known as St. Mary’s Cathedral, which is the oldest church in Estonia. The original wooden church on the site was already there when Danish crusaders conquered Toompea in 1219. Over the next two centuries, the building was replaced by a larger stone structure that was taken over by the Lutherans in 1561. The church was heavily damaged in the 1654 fire that destroyed every other building on Toompea Hill, but its fifteenth-century outer walls survived and the rest was restored soon afterward. A new tower was added in the late 1700s. The cathedral now belongs to the Estonian Evangelical Lutheran Church and is the seat of the Lutheran Archbishop of Tallinn.

We didn’t fully realize how much difference in elevation there is between “upper” Old Town and “lower” Old Town until Sergei led us to one of the viewing platforms on a precipice near St. Mary’s.

View of “lower” Vanalinn

From there we could see a panorama of red roofs and green trees that stretched all the way to the sea. Our view was dominated by the spire of St. Olaf’s Church, which is nearly as old as St. Mary’s and may have been the tallest building in the world at the end of the sixteenth century. That claim is hard to prove as the definition of fathoms has not always been consistent, but what is certain is that the steeple has been struck by lightning at least ten times, causing the whole church to burn down thrice. The current spire measures nearly 124 meters high, and was used for radio transmissions and surveillance by the Soviets during the last half of the twentieth century. A local ordinance prevents any new construction from exceeding the height of St. Olaf’s spire, thus protecting Tallinn’s historic skyline. The church originally served a Catholic community but became Lutheran after the Reformation. In 1950, however, the Lutherans realized that they owned more churches in Tallinn than they needed and decided to turn St. Olaf’s over to the Baptists.

Descent to lower town

Tallinn’s theater and ballet schools are located on the site of the city’s first school

A street vendor making caramel-coated nuts

From the viewing platform, we climbed down a long set of switchbacking stairs set against the ancient castle wall. As we descended we got a good view of Stenbock House, built in the 1780s as a courthouse but passed on to a nobleman named Stenbock when the overextended imperial government could not afford to complete it. Count Stenbock used the place as a residence, but in 1899 the government reacquired the property and began using it as a courthouse as originally intended.

The Estonian prime minister’s residence overlooks Tallinn and the sea from “upper” Old Town

During the Soviet era, the government—apparently strapped for cash once again—failed to maintain the building, so by 1991 the mansion was at serious risk of collapsing. The Estonian government undertook a complete renovation and reopened the building in 2004 as the official residence of the country’s president.

The towers of Vanalinn

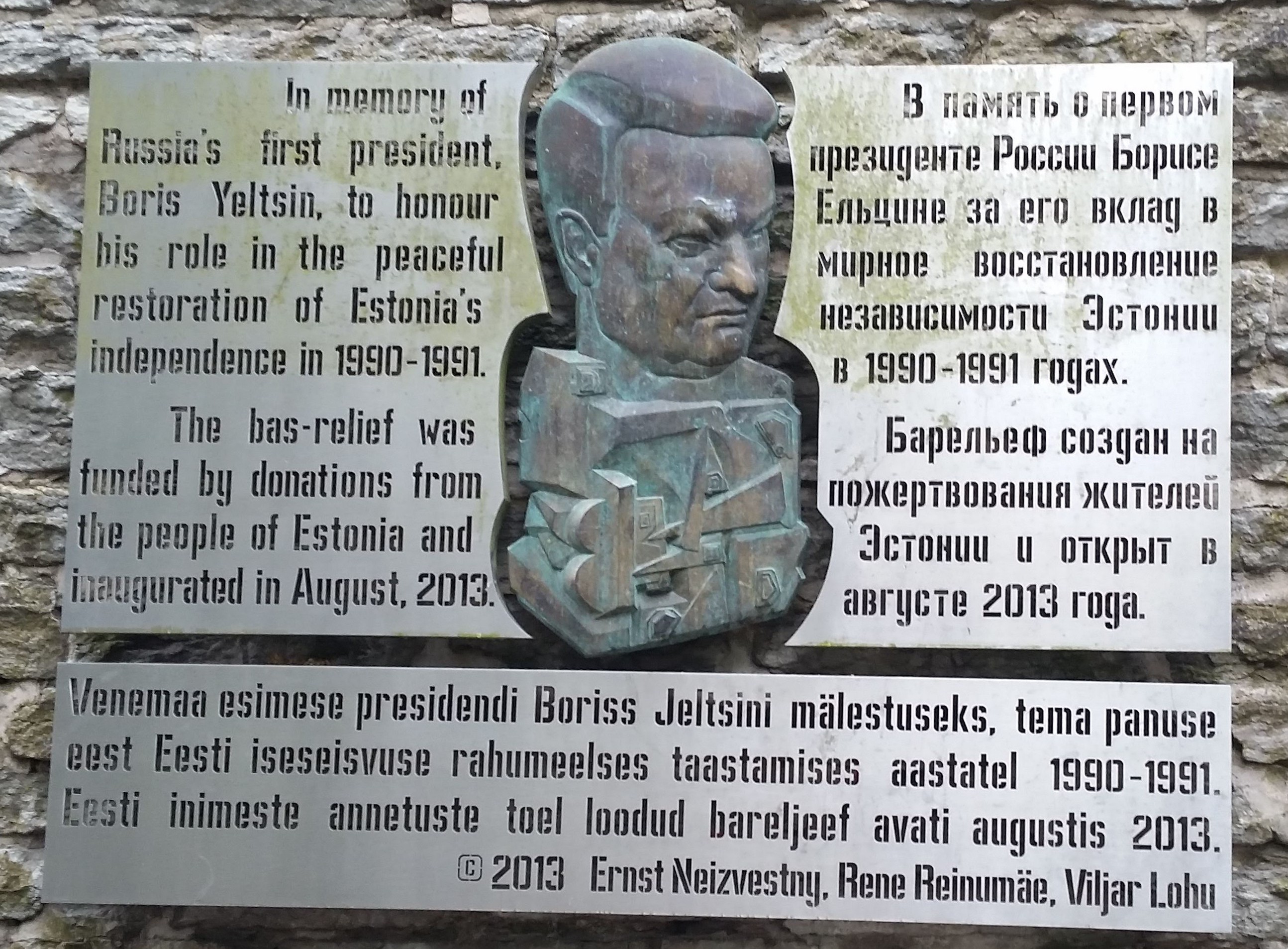

Tribute to Boris Yeltsin

At the bottom of the stairs we found ourselves in the park outside Vanalinn, but from that vantage point we could better see the fortifications that still surround the medieval city. On one wall we noticed a fairly new plaque honoring Boris Yeltsin, the former Russian president, for “his role in the peaceful restoration of Estonia’s independence 1990-1991.”

Outdoor performance venue of the Tallinn City Theatre

Reentering Vanalinn through a lower gate, Sergei led us along a back street that runs behind the Tallinn City Theatre. As we walked, he shared a personal experience from his first visit to the U.S. in August 2002, when he was a college student. Sergei didn’t think he’d be able to buy alcohol while he was there because he hadn’t turned 21 yet, but because his 6 October 1981 birthdate was printed in his passport European-style as 6/10/1981, the Americans who checked his age all thought he had turned 21 on June 10 and let him buy whatever drinks he wanted. Even though we couldn’t condone allowing an underage student to buy alcohol, we had to admit it was a funny story.

Tallinn City Theatre

Inside the lobby of the Tallinn City Theatre

The Tallinn City Theatre occupies a series of medieval row houses that once belonged to local merchants. The top floors—now combined into a large rehearsal space for the repertory company—would have been used in the past as warehouses. The lobby and administrative offices are on the ground floor, and the cellars have been transformed into a tavern for theatergoers. We were sorry that we couldn’t stay for tonight’s performance, which will be held in the outdoor venue behind the buildings. (It’s probably just as well, because the play will be presented in Estonian, without supertitles.)

The tavern inside the Tallinn City Theatre

Estonian History Museum, the former Great Guild Hall

House of the Blackheads

The brightly painted entrance to the House of the Blackheads dates from the 1640s. The portrait at the top is St. Mauritius

The merchants whose homes and warehouses are now a theatre undoubtedly belonged to the Great Guild, an association of traders and artisans that operated in Tallinn from the 1300s (maybe even earlier) until 1920. This group would have met in the Great Guild Hall, a big, gothic-style building located down the street and around a corner from the theatre and has stood there since 1410. The hall provided a place for members to conduct business, relax, eat, and drink. Wine was stored in the cellar, which was turned into a commercial wine bar during the nineteenth century. At times, the building also served as a cultural arts center for the community, hosting concerts and plays. In 1952, the Guild Hall became the home of the Estonian History Museum. Its permanent exhibition is called “Spirit of Survival: 11,000 years of Estonian History”—an appropriate tribute to a people who kept their ethnic language and traditions alive despite centuries of official oppression.

The Brotherhood of the Blackheads, another fraternity for young, unmarried merchants who did not yet qualify to join the Great Guild, met in their own hall nearby. The House of the Blackheads also welcomed ship owners and foreign traders. The Blackheads’ patron saint is Mauritius, a black Egyptian who was a commander in the Roman army and a notable Christian who refused to harass other followers of Christ despite orders from his superiors. Today the House of the Blackheads is the home of the Tallinn Philharmonic Society, which organizes intimate chamber and jazz performances in the refurbished hall as well as large-scale concerts in other venues (such as the Convent of St. Bridget).

Old Town Square

Old Town Hall

In the middle of Old Town is the Old Town Square (of course), and the Old Town Square is dominated by the old Town Hall (also no surprise). Dating from the fourteenth century, Tallinn’s town hall is the oldest still standing in the Baltic region. The two-story building served as the center of the city’s political administration until 1970, and now is used as a museum and concert venue. In 2004 it was declared a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

Vana Toomas

The figure on the weathervane atop the Town Hall, known as Vana Toomas (Old Thomas) has been a symbol of Tallinn itself since 1530, when the original copper sculpture of Old Thomas was placed on the spire. It represents a man who, as a boy, was given the honorary title of Town Guardian for Life after he repeatedly won an annual bow-shooting contest organized by local landowners. (As a serf, he was not allowed to claim a monetary prize.) According to legend, the boy took his title seriously, joining the local militia and acting as a sort of town constable when he got older. The children of Tallinn loved Old Thomas because he used to give them candy as a reward for good behavior. When Old Thomas died and children too young to understand death began asking where he had gone, the town elders decided to put a figure of Old Thomas on the steeple, where he could continue to watch over the town. Parents told their kids that Old Thomas was still monitoring them, so when they felt the children had been especially well behaved, they would put candy under their pillows and say it came from Old Thomas.

Sergei said goodbye to our group in the Town Square, but not before meticulously and repeatedly explaining how to get back to the cruise ship port from Vanalinn on foot. We assured him that we could find the way (which basically involved walking through the Great Coastal Gate and turning right at the main road), and then set off exploring on our own for another hour or so before we needed to be back onboard the Star Breeze.

We bought a small watercolor of Tallinn’s Vanalinn for our art collection

A souvenir chess set for political junkies

Revali Raeapteek (Town Hall Pharmacy), in continuous operation for nearly 600 years

Opposite from the Town Hall is the Revali Raeapteek, or Town Hall Pharmacy. (Reval was the official name of the city of Tallinn from the Danish conquest in 1219 until 1918. We aren’t sure exactly why the name was changed when the country declared independence, but perhaps it was to signal that Estonians would no longer simply accept whatever outsiders had imposed on them.) Early records indicate that by 1422 the Revali Raeapteek was already on its third owner, making it one of the oldest continuously operating pharmacies in Europe. From 1580 until 1911, the shop was owned and operated by the Burchart family, headed by ten generations of apothecaries who all were named Johann. After Johann Burchart X died without a male heir, his surviving sisters decided that it was time to sell.

Entrance hall of Restaurant Balthasar, which shares a building with the Town Hall Pharmacy

During the 1990s the building was completely renovated to accommodate a modern pharmacy as well as a museum of antique chemistry equipment and medical instruments. The second floor has become the Restaurant Balthasar, named for historian Balthasar Russow, who lived above the apothecary shop in the sixteenth century.

Maiasmokk Café, “beloved meeting point since 1864” according to an English inscription on the display window

Around the northeast corner of the square from the pharmacy is the the Maiasmokk Café, the oldest continuously operating café in Tallinn. Having opened 1864, it’s nowhere near as ancient as the pharmacy, but its interior has remained unchanged for more than a century. Prior to the current café, the property was owned by a confectioner who also ran a coffee house. The Maiasmokk became famous for its marzipan, counting the Russian imperial family among its customers. Today, in addition to serving coffee and pastries, the café includes a museum with displays of antique candy molds and marzipan painting demonstrations.

Bakery connected to the Church of the Holy Spirit

Behind the Town Square is a small bakery in a house built in 1656. We learned that in Estonian, there are three different words for bread: sai is white bread, leib is rye or black bread, and sepik is brown bread. Because of its proximity to the Church of the Holy Spirit and an inscription above the door that reads “In Christ is My Hope,” this bakery is sometimes a stop along a pilgrimage made by children in Tallinn’s Christian schools.

Art nouveau KGB headquarters

As we headed toward Vanalinn’s main gate on our way back to the port, we noticed the unassuming entrance to a notorious KGB prison, which for decades disgraced what was otherwise one of Tallinn’s most elegant art nouveau buildings. For a few years after Estonia declared independence in 1918, the former residential building was the seat of the fledgling provisional government, and later housed the Ministry of War. In 1940, however, it became the headquarters of the local branch of the KGB. Alas, we did not have enough time to go inside to view the upstairs interrogation rooms and basement prison cells.

St. Olaf’s Church from street level

Gothic-period relief sculptures on the walls of St. Olaf’s helped the illiterate learn Bible stories

Before passing through the main gate we got a closer view of St. Olaf’s Church, which looked much different from street level than it did from the top of Toompea Hill. From this vantage point, we could better appreciate the tracery of the tall gothic windows and the relief sculptures on the exterior walls.

The Great Coastal Gate was built in the 14th century to control traffic between the port and Vanalinn’s market square

The 17th-century artillery defense tower, nicknamed “Paks Margareeta” (Fat Margaret), now houses the maritime museum

The pedestrian walkway back to the cruise ship pier has been decorated with a series of street murals celebrating the centennial of Estonia’s original declaration of independence.

On deck for the “Sail Away”

At 5:00 p.m. we were back on the deck of the Star Breeze for our “Sail Away” ceremony, which was accompanied by picture-perfect weather and the stirring theme from 1492: Conquest of Paradise by Greek composer Vangelis. We think of this as the classic sail-away song because it was played at every departure during our Aegean cruise on the Wind Star in 2017, but this was the first we had heard it on the Star Breeze.

Escargot

Nancy’s antipasti plate

Grand Marnier soufflé

Tonight we were seated in the AmphorA dining room across from NJ and Mary-Anne. Michael and Allison (seated down the table) ordered the escargot, which they pronounced “okay,” but not the best they’d ever had. Michael’s butter lettuce salad and poached salmon with frites were more satisfying. Nancy enjoyed her antipasti plate, Moroccan chicken-chickpea soup, and Imam Bayildi: a small, whole eggplant stuffed with tomatoes, onion, and garlic, and simmered in olive oil. The name, which means “the imam swooned,” comes from a Turkish tale about an imam who fainted with pleasure when his wife served him such a dish. For dessert, both of us ordered the equally swoon-worthy Grand Marnier soufflé.

Most nights during this cruise, Michael has supplemented his sweet dessert with the European-style cheese course. This evening he was disappointed when the waiter presented him with a plate containing a small bunch of grapes, several crackers, a bit of brie, and a huge hunk of bleu cheese—one of the few cheeses he does not like. Nancy loves bleu cheese but was already too full to take more than a taste. When the waiter returned, she asked him to wrap up the cheese so she could enjoy it later with a ripe pear we had back in our room. Well, the plate disappeared, but the cheese did not return before we left the dining room and we sort of forgot about it in our hurry to the auditorium, where the crew’s variety show was due to begin.

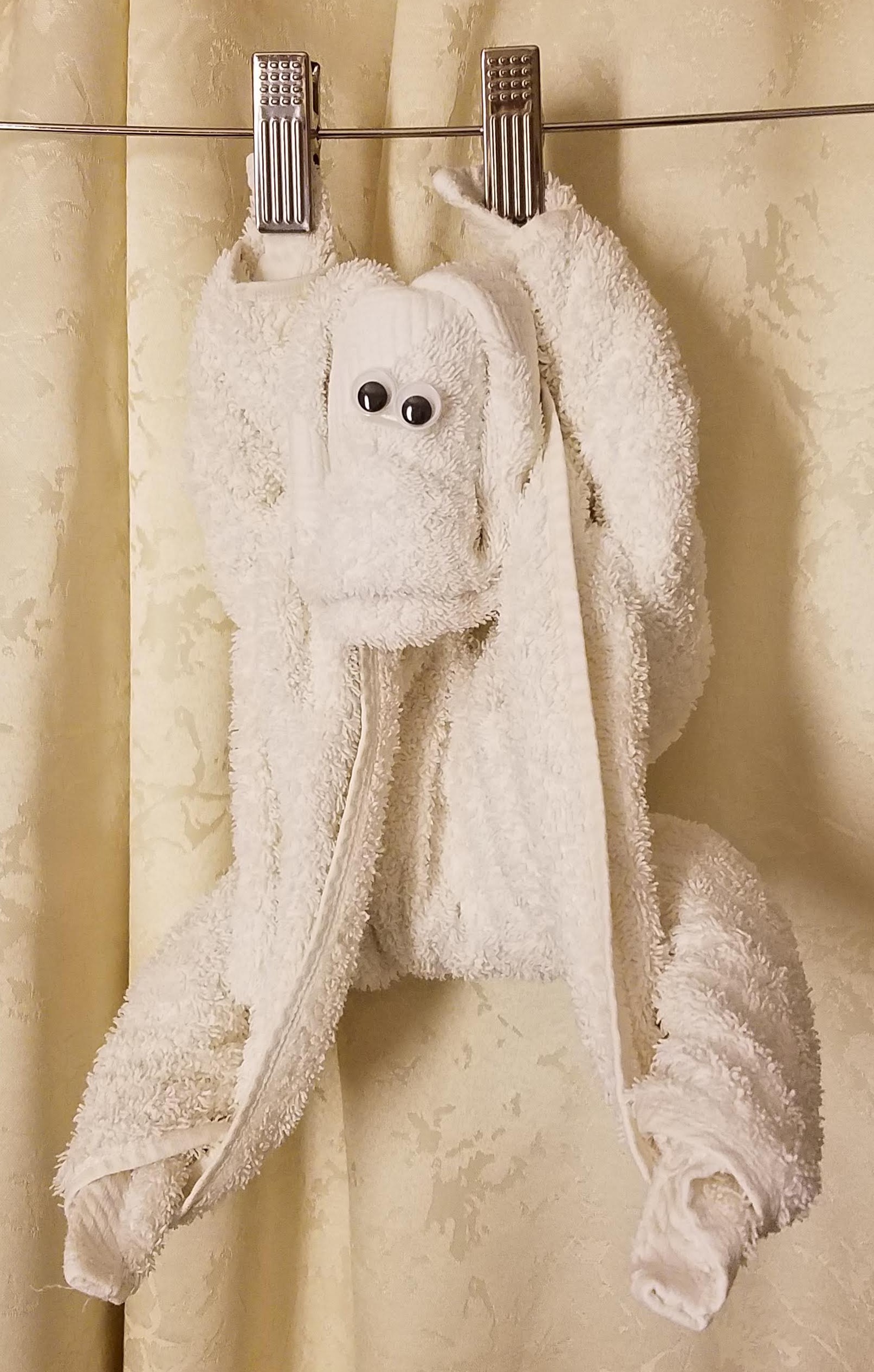

This has to be a monkey, right?

Not surprisingly, the term variety could be applied to the quality of the acts as much as to their content and style. The show began auspiciously, with a pretty good Elvis impression performed by one of the dining room servers, and we were intrigued by an elaborately costumed narrative dance presented by Sahid, a laundry worker from Java. The show’s nadir was a “comedy” routine by Victor, the Portuguese sommelier, who introduced his act by flexing his aging biceps and proclaiming: “I work out; I’m sexy and I know it.” It went downhill from there, interminably. One unfortunate member of our group (whom we will call “Bruno”) was among those dragged onstage as Victor’s “assistants.” We were impressed by Bruno’s valiant attempt to maintain dignity when instructed to “shake his booty,” and not so much by Victor’s attempt at humor. One would expect a sommelier to have better taste. More enjoyable acts included a dance by a group of Filipino women that ingeniously demonstrated the many ways a malong (a traditional tube-shaped garment) can be worn; later in the program the same ensemble did a more upbeat hip-hop number. A group of seven Indonesians performed the “Dance of a Thousand Hands,” which involved synchronized clapping. Another waiter named Roy did a respectable rendition of “You’ve Got a Friend,” accompanying himself on the guitar and inviting the audience to sing along (which at least half of us did). But without a doubt the best performer of the evening was Kuba, the Polish destination manager, whose harmonica wails the blues.

By the time we returned to our room it was 11:00, but we got to set our clocks back an hour because we expected to move out of the Eastern European time zone overnight. Tonight’s towel animal was a monkey hanging from the curtain rod between the bed and the sitting room. When we pushed the curtain aside, we found that room service had provided us with a new cheese plate, presumably in place of the leftovers Nancy had requested to get wrapped at dinner. The only problem was that this plate did not include any bleu cheese, which had been the object of the request. The dining room staff may speak good English, but apparently they don’t always understand exactly what we’re trying to say.

Leave A Comment