We were grateful for the hot water flasks left in our bed last night. Even though the temperature never dropped below 55°F, with no other source of heat in the tent it’s likely that we would have spent the night shivering without them. To our surprise, the flasks were still warm when we woke up, making it all the harder to get out of bed. The water in the shower warmed up fairly quickly, however, so we didn’t have to shiver very long after ducking between the canvas flaps that separate the bed area from the bathroom at the back of the tent.

Sunrise

Jody and Dyrk

Geoffrey

After ensuring that the zippers on the outer walls were securely closed before we left (there are no locks and therefore no room keys, but we still must take precautions against baboons), we headed for the lodge to meet the group for the early-morning game drive. It was lovely to find sliced pound cake and hot chocolate made from real milk waiting on the hospitality table–just the right thing to tide us over until breakfast.

This morning we teamed with Jody, Dyrk, and driver Geoffrey. Our sunrise view included the majestic silhouette of Mt. Kenya, which heretofore had been completely hidden by low-hanging clouds. From our vantage point, it looked like a buddhist temple rising in the east above the forest.

View of Mt. Kenya

White rhino family

Baby white rhino

The first animals we stopped to observe were some white rhinos. We had already learned that white rhinos generally travel in families, but Geoffrey gave us some additional insights into their behavior. When groups of white rhinos move, they allow the babies to take the lead so that the adults can more easily keep an eye on them. Mothers have primary responsibility for their own calves, but others in the herd help ensure that the juveniles stay safe. The less social and more aggressive black rhinos prefer to travel alone. The exception would be a mother with a calf, but unlike white rhinos, black rhino mothers lead and expect their calves to follow–making the babies much more vulnerable to predators. (Upon receiving this significant bit of information, Michael commented: “There’s a sacrament meeting talk in that.”)

Female and male zebra

As we drove past herds of grazing zebras, Geoffrey asked if we could tell males from females without looking at their genitals. We were stumped until he pointed out that females have slightly duller coats than males, with less contrast between the black and white stripes. (The difference is very subtle; we think it’s easier to just look at their genitals.) Our guide also told us that many animals of the same species develop color variations based on their environment. For example, rhinos that live in cool climates tend to have darker hides than their warm-climate counterparts; the same is true of lions. Elephants and warthogs tend to take on the hue of the soil wherever they live.

Tawny eagle

Some of our guides seem to have a special fondness for birds, not only pointing them out and waiting patiently while our auto-zoom lenses try to focus on such tiny, unpredictable targets, but always teaching us something about the birds’ habits. Geoffrey is one of these. He told us that tawny eagles feed mostly on small mammals, snakes, and other birds, but are capable of grabbing a dik-dik twice its own weight. The eagle will lift the little antelope into the air, then drop it to break its neck. The bird can then enjoy a hearty meal without having to wrangle a heavy load on the wing.

“Do you hear that loud chirping?” Geoffrey asked us at one point. (We could.) “Where do you think it’s coming from?”

Pied wagtail

We looked around and finally spotted a small black-and-white bird on the ground some distance away. “That’s a wagtail,” said Geoffrey. “Little bird, big voice!” (We forgot to inquire about the identity of a bird we had heard yesterday, in the tent area. Nancy has begun calling it the “hokey pokey bird” because it coos in exactly the same rhythm as: “You put your left foot in, you put your left foot out.”)

Jackson’s hartebeest

During our drives today, we learned that the Ol Pejeta Conservancy cares for some wildlife literally from the cradle to the grave. Geoffrey took us past a special breeding area for Jackson’s hartebeests, a grazing animal that is endangered in this part of Kenya.

“Hartebeests are not very good mothers, not very good caretakers of their young,” he explained. “It is very easy for predators to pick off the little ones from the herd, so their numbers are getting low. The Conservancy made this fenced area just for breeding hartebeests. They removed all the predators so the babies can have a better chance to survive.”

Black-backed jackal

Moments later we got a lesson in predator behavior when a jackal crossed in front of our vehicle, scattering a group of gazelles. Geoffrey said he was surprised that the fox-like animal appeared to be alone.

“Jackals mate for life, and they usually they hunt with their partners,” he said. “The female, she may be hiding somewhere with the pups this morning.” He went on to tell us that jackals, hyenas, and lions are canny hunters, employing teamwork whenever possible to secure a meal for themselves and their families. Jackals generally close in on their prey from two directions; hyenas and lions like to set up ambushes.

He may be resting, but he is keeping his eye on us

We stopped for a while to observe three lions–one male and two females–at rest among some trees. We’d noticed that many of the small acacia trees in this reserve are “decorated” differently from taller ones in the Samburu Reserve. Instead of weaver birds’ nests, many trees here are covered with little black balls about the size of a grape–but they’re obviously not fruit.

So we asked Geoffrey: “What are all those little black balls on the acacia trees?”

Ant balls on a young acacia tree

“Oh, yes, I am glad you asked,” he said. “That is very interesting. The black balls, they are homes for ants. They have a sweet liquid inside that attracts the ants. The acacia tree grows them when it is small so the ants will move in. When an elephant or giraffe comes and tries to eat the tree, the shaking makes the ants come out of their homes. They sting the animal and make it go away. So the tree and the ants cooperate, you see: the tree provides food for the ants, and the ants protect the tree from being eaten until it is big enough to survive on its own.”

We didn’t linger too long over the dozing lions because Geoffrey wanted to make sure we didn’t miss the action at one of the conservancy’s man-made waterholes. These have been constructed in strategic places throughout the park, fed by pipeline from a central water system rather than from wells because the groundwater in this area is too saline for the animals to tolerate.

Elephants at the man-made waterhole

The waterhole we visited this morning was deserted when we arrived, but within a few minutes we saw a herd of elephants coming over a rise and heading in our direction. A large cow was in the lead, looking back occasionally to make sure that the group stayed together. As they neared the water, the group picked up speed. Soon some of the younger ones broke from the herd and began running, obviously eager to get a drink, but when they got to the waterhole they respectfully restrained themselves until the lead elephant and other adults had taken up prime positions. Then it was like kids at a birthday party when they’re told that it’s time for cake and ice cream: the young ones jostling each other aside as they tried to wriggle their trunks into the water. For a few minutes, each animal seemed intent on sucking water into its trunk and then transferring it into its mouth as efficiently as possible, but once their immediate thirst had been quenched the fun began. Adults and juveniles alike splashed and sprayed each other, and when they were thoroughly wet, they lumbered away from the water and began flinging dirt onto each others’ backs–natural sunscreen and insect repellent.

We noticed that when the elephants had had their fill and were starting to move away from the waterhole, a herd of zebras was waiting in the wings to take their place. Geoffrey explained that there is a code of waterhole etiquette with a definite hierarchy among the animals: zebras and giraffes defer to the elephants, antelopes to the zebras, and no matter when they arrive, everybody yields to the rhinos.

Geoffrey advised us that when we visit the Maasai Mara Reserve later in the week, we will not see as many elephants. “They don’t like noise and confusion, so they move away from the Mara during the wildebeest migration. On the other hand, you will see more predators there because the abundance of wildebeests means an abundance of food.”

Breakfast buffet at the Sweetwaters lodge

Mark, Lynn, Roger, Norene, and Jody at breakfast

At that point we left the waterhole and returned to the lodge, where we could enjoy some food and drink ourselves. Although we often choose more exotic juices like mango, passion fruit, pineapple, and hibiscus, the fresh orange juice here is amazing! This morning we also tried the crepes and oat porridge.

Norene and Roger are Dyrk’s aunt and uncle

Jackson

Today we had another game drive soon after breakfast, for which we teamed with Roger and Norene, who are from Reno, Nevada. Jackson was at the wheel. The other drivers have nicknamed him “Michael Jackson” and he can do a pretty good moonwalk, but he’s better known as a crazy driver. At least, that’s what we’ve heard.

He didn’t try any outrageous moves as he drove us toward a grass-covered dam, where two lions perched on top were having fun preventing several giraffes from drinking at the spillway. The poor giraffes obviously were thirsty, but even though the lions were on the opposite side of the spillway, the giraffes were reluctant to spread their legs and lower their heads enough to drink.

He didn’t try any outrageous moves as he drove us toward a grass-covered dam, where two lions perched on top were having fun preventing several giraffes from drinking at the spillway. The poor giraffes obviously were thirsty, but even though the lions were on the opposite side of the spillway, the giraffes were reluctant to spread their legs and lower their heads enough to drink.

Giraffes try to determine the lions’ intentions

Giraffe contortions in order to drink

“When their legs are spread out, they’re very vulnerable,” Jackson explained. “If the lions were to attack, the giraffes would not be able to get up fast enough to use their legs to kick, and kicking is their only defense.”

Birds around the waterhole were less concerned about the lions, knowing that they wouldn’t make much of a meal for a big cat. We discovered that Roger and Norene are amateur birders, too, so when we asked Jackson to point out and take time for us to photograph interesting avians, he was happy to comply. When he stopped near a herd of cape buffalo so we could get photos of some oxpeckers, Jackson asked if we knew what to call a sleeping male. The proper term, he said, is bulldozer.

Red-billed oxpecker atop a cape buffalo

White-bellied bustards

fiscal shrike

Lilac-breasted roller

White-browed coucal

Three-banded plover

Egyptian goose

We also asked Jackson if he would take us back to the rhinoceros cemetery, which Geoffrey had pointed out to us earlier although we didn’t have time then to stop.

Rhino cemetery

This monument honors Ringo, a white rhino who died of natural causes at the age of only 9 months

Ol Pejeta’s rhino cemetery honors rhinos that have died in the reserve, most of them not from natural causes, but as a result of poaching and other unfortunate “human-wildlife interactions.” This was one of the few instances when we were allowed to get out of the vehicle (briefly, and only after checking to make sure there were no animals close by) so that we could read the epitaphs on each monument. It was sobering to read about each rhino’s life and death. The most recent memorial is for Sudan, the very last male of the northern white rhino subspecies. He had to be euthanized about five months ago at age 45, after contracting a leg infection that weakened him so much that he could no longer stand. Sudan had spent most of his life in a Czech zoo, but was brought to Ol Pejeta in 2009 along with the only two female northern white rhinos still in existence. The plan, of course, was for them to breed, but unfortunately they never produced any offspring. Even though Ol Pejeta scientists have saved sperm from Sudan and a few other northern white males, there’s little hope that a biologically pure northern white rhino will ever be bred because one of the remaining females is sterile and the other is incapable of carrying a calf to full term. These two are kept in a separate, fenced-off, predator-free area where they help young rhinos who were born in captivity learn how to survive in the wild.

A prowling cheetah: one of the reasons the Conservancy provides extra protection for some endangered grazing animals

Domesticated Ankole cattle

Near a compound of Conservancy buildings, we were surprised to see a herd of cattle with huge horns driven by what we suppose should be called a cowboy. Jackson confirmed that this was a domesticated Ankole herd, brought from Uganda so that Ol Pejeta’s abundant oxpeckers can help reduce the cows’ tick infestation.

Mother zebra awakened her baby as we approached

Baby warthog

Tawny eagle on her nest in a fever tree

Our drive ended with a series of mother-and-child vignettes. First, we noticed a baby zebra asleep in the grass and then felt bad when its mother nudged it awake and urged it to move away when we got a little too close. Nearby, a mother warthog didn’t seem to care when we pulled up to next to her and her child; they went right on eating. Finally, we spotted a tawny eagle sitting on her nest at the top of a fever tree. (This variety of acacia was named by European settlers, who thought perhaps the trees were responsible for the fevers that plagued them in the swampy areas where the trees grow. Native medicine men knew, however, that the acacia’s roots and bark yield quinine, a natural treatment for preventing malaria and yellow fever.)

When we returned to the lodge, our immediate assignment was to pack our luggage and bring it to the loading area, reserving a only small bag containing what we would need overnight and tomorrow morning. The reason is that Discovery XA’s six drivers are taking our safari vehicles on to the Maasai Mara, an eleven-hour drive from Ol Pejeta. Fortunately, we privileged American tourists will not have to endure that long, bumpy ride; instead, we will do some more sightseeing this afternoon and then make a 90-minute flight tomorrow in a couple of chartered planes. The small planes won’t have room for all our luggage, however, so we must send it ahead in the Land Cruisers. Carol said goodbye to the group along with the drivers, although she won’t be meeting us in the Mara as they will be; she’s returning to Salt Lake City to help her daughter with the triplets and another preschooler while her son-in-law is away from home on business. We’re grateful for Carol’s dedication to ensuring that all our travels go smoothly–and her unflappability if the road unexpectedly turns rough. We’ll miss her!

Stir-fry bar

Many of us chose to eat a tasty made-to-order lunch from the stir-fry pasta bar today, finishing it off with a cup of passion fruit mousse. More notable was the lively discussion of healthcare costs and medical insurance that we carried on across the table with Pam, Eric, Lynn, and Mark. All of us are either in or near retirement, so this is a hot topic for our cohort right now.

Lynn, Michael, Jim, and Mark chat on our verandah

Big windows in the Sweetwaters Serena lodge allow guests to view animals at the adjacent waterhole

The driveway near the lodge is surrounded by plumbago bushes

Eva, laying wet socks out to dry on her porch, is just visible under an unusually large umbrella tree

Lynn, with a poinsettia that has survived many Christmases

Mature acacia trees have long, wicked spines

Sacred ibis outside the dining rooom

After lunch we had some much-needed down time. We spent a while chilling with our neighbors, laughing as a couple of cape buffalo had what appeared to be a glorious time rolling in the mud at the waterhole. Michael took a nap while Nancy repaired the torn strap on Lynn’s purse with a needle and thread she produced from the bottom of her own handbag. As she sewed, she reflected on our lunchtime conversation and wondered what the smiling, attentive dining room staff must have thought as we discussed our first-world problems. Do they resent us for the sense of privilege we must exude, or are they simply grateful for our business?

When we arrived yesterday, porters had waited patiently for us to identify our luggage so they could deliver it to our tents while we ate lunch

What do our native servers eat at home, after they’ve cleared our plates and scraped off the ugali (a sticky bread that resembles grits) that we rejected because it failed to satisfy our delicate palates? Do our drivers’ accommodations have private showers and fluffy towels? Here at the Sweetwaters Serena Tented Camp (which, according to a plaque outside the lodge, welcomed Edward, Prince of Wales, in the 1920s–or maybe it was the Duke of Gloucester) we have never felt more like Downton Abbey’s Crawley family: “entitled” to our comforts by virtue of our comparative wealth. Can we, like the Crawleys, justify the ease with which we expect others to wait on us by reasoning that our money is supporting the local economy and lifting the servant class out of poverty? We’re still trying to decide.

Our trusty Land Cruisers. Nancy thinks their oversized antennas resemble rhino horns

Later in the afternoon, the group was driven to the chimpanzee sanctuary within the Ol Pejeta Conservancy. Because our Land Cruisers are now on the way to Maasai Mara, the Gees rented a bus for this short drive, as well as for tomorrow’s drive to the airstrip. Michael and Nancy were some of the first to board the bus and began to wonder how all twenty-four of us were supposed to fit in only eighteen seats. What we didn’t realize until Jim showed us is that each of the six rows is fitted with an extra seat that folds down into the aisle. Such an arrangement would never fly in the U.S. because of the obvious safety concerns posed by the lack of an aisle when every seat is filled, but Kenyans can’t afford to be as fastidious about safety as Americans are. (Remember those motorcycle taxis navigating a busy road with four passengers?) Jim told us that even Toyota Land Cruisers–favored by Discovery XA because they’ve proven to be the most reliable safari vehicles in Africa–are not considered safe enough for import to the U.S. because they don’t meet American emissions standards.

As it turned out, we needed only twenty-three passenger seats because Eric, who had an unpleasant encounter with some unruly chimps last year while visiting Bali, decided to stay back at the camp.

A moat divides chimps from visitors–and different chimp “families” from each other

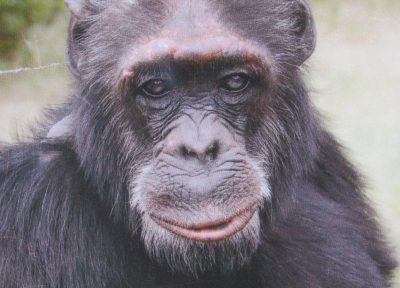

The Ol Pejeta-Sweetwaters Chimpanzee Sanctuary provides what Tom lovingly called “assisted living” for chimps that have been injured or rescued from inappropriate human ownership. The sanctuary is divided by a moat into two separate territories to prevent two distinct chimp “families” from engaging in the equivalent of gang warfare. The moat also separates the thirty-nine chimps currently living here from their human visitors. It isn’t very wide, but no matter; chimps cannot swim because their are legs too short and their arms too long.

Lufa and Numkuru

Greybeard

William

Poco

The sanctuary’s observation deck

From our side of the moat we could see Lufa, a 26-year-old female who is the leader of one family. She was accompanied by Numkuru, who busied himself gnawing on a sugar cane during our visit. William, age 29, is one of the largest in the sanctuary at 55 kilos, but he’s going bald. Greybeard, a former leader, has lost his canine teeth. Passing the other side of the sanctuary on our way to an observation deck we could see a chimp named Poco, but he probably couldn’t see us. The guide told us that he needs cataract surgery, but at 38, he is too old for it. Fortunately, Poco has a devoted friend named Socrates who spends 75 percent of his time taking care of Poco, grooming him and walking next to him as an extra set of eyes. The youngest chimp in the sanctuary was born here twelve years ago, but she’s not the most mischievous resident. That distinction goes to another female, called Ayelit, who was brought to the sanctuary about six months ago. The guide says that one of her favorite tricks is to short out the electric fence and encourage her companions to escape. She’ll then sit quietly inside with her arms folded, watching with amusement as the others get in trouble.

A shopkeeper once kept a chimp confined to this cage for over a decade, allowing customers to tease and traumatize the animal until it was rescued and brought to the sanctuary (picture is missing)

Custom crate designed to smuggle baby chimps

On our way out of the sanctuary, the guide directed our attention to a wooden crate with six small compartments. The crate had contained six baby chimps that someone tried to smuggle onto a flight to Cairo. The animals were confiscated at airport, but two of the chimps died soon afterward; the others–now known as the “Four Musketeers,” were brought to the sanctuary. It takes a while for a newly introduced chimp to be accepted by one or the other of the primate “families” here, but eventually most find a place within the community’s established order. If they don’t, they will keep to themselves and the human staff will have to provide extra attention. As we left, staff members encouraged us to consider adopting a chimp by agreeing to send a donation every year in return for a photo and regular updates on how the chimp is doing. We’re not sure we really want to know. Although we’re confident that they’re receiving the best possible care, none of the chimps we saw today looked very happy–just resigned.

Michael is in the northern hemisphere, Nancy in the south

On our way back to the lodge, the bus stopped and let us off briefly so we could take pictures next to a sign marking the equator. While we were all together, we took a group photo (minus Eric), and then Jim gave us instructions for checking out of the camp tomorrow morning.

“Yeah,” Paul piped up. “Don’t forget to turn in your zippers!”

In the free time we had before dinner, we took advantage of the wifi to start uploading pictures from the camera to Michael’s phone. We also took a walk around the compound, along the way picking up Lynn and Bryce, whose spouses were otherwise occupied. One cannot go very far here before reaching the electric fence, but tonight we found an enclosure where a couple of camels are kept to provide guests with the equivalent of a pony ride. (We rode camels in Petra a few years ago, and once was more than enough.)

Tonight’s dinner buffet included more delicious Indian fare as well as a pretty good bread pudding with custard sauce, chocolate-drizzled meringues, and a creamy pistachio “bouche.” We’re reluctant to leave Sweetwater’s outstanding food and service, but we’re excited for a new set of adventures in the Maasai Mara.

Leave A Comment