When Nancy was growing up her family often took Sunday afternoon drives, exploring new territory around Southern California. We decided that while in New Zealand, we would resurrect that family tradition.

When Nancy was growing up her family often took Sunday afternoon drives, exploring new territory around Southern California. We decided that while in New Zealand, we would resurrect that family tradition.

Scenic drive to Raglan

We wanted our first Sunday drive to be someplace interesting, but not too far. So we chose Raglan, a beach town on the west coast about 45 kilometers from our flat. On winding, hilly roads, that translates into roughly a 60-minute drive each way.

The drive was beautiful.

About 40 minutes in, however, Nancy suddenly realized that maybe this particular excursion had not been the best choice for the day. It was clear, sunny, and pleasantly warm, one of the first days of the summer (we had been told) that had not been cool and rainy.

Behind an antique car on the one-lane bridge; can you guess the make of the car?

“It just occurred to me that we’re likely to run into a lot of beach traffic,” she said out loud, and indeed, as we approached Raglan a few minutes later on the only well-maintained road in and out of town, we found ourselves engulfed in a swarm of vehicles full of sunseekers. There was a 20-minute wait to cross the one-lane bridge over the inlet just beyond the center of town, but the vibe we felt emanating from the other cars was almost like that in the opening scene of La La Land: unhurried, communal, harmonious. Yes, we were all stuck in a traffic jam, but we were all stuck in it together. And look, doesn’t the glorious scenery make you feel like singing?

The Raglan beach

We passed the turnoff for the Raglan “Domain” (the Kiwi term for a public park or recreation area) but opted to not stop; neither did we stop in town (nowhere to park at either location), but instead continued driving around the bay. However, since we had not yet purchased a road atlas and weren’t sure how far our GPS signal would stay with us, we decided that we’d better turn around and get back on the main road before we got lost. Again, we had a 20-minute wait at the one-lane bridge. This time we were behind a caravan of antique cars whose drivers couldn’t have cared less about the delay.

Blue Nile lilies (agapanthus) grow wild here in New Zealand, like weeds

In the well-thumbed copy of Fodor’s New Zealand that had guided us through our visit six years ago, Michael had read about another scenic spot only 20km south of Raglan that we would have time to see before heading back to Hamilton: Bridal Veil Falls, on the Pakoka River. As we climbed into the green semitropical bush that began to cover the hills, we realized that this place likely would bear little resemblance to a waterfall in the steep, red rocks of Utah’s Provo Canyon, which also is called Bridal Veil Falls. (There are no tree ferns in Utah.)

As we got out of the car near the trailhead to the falls, we were stopped by a young couple coming back to the parking area.

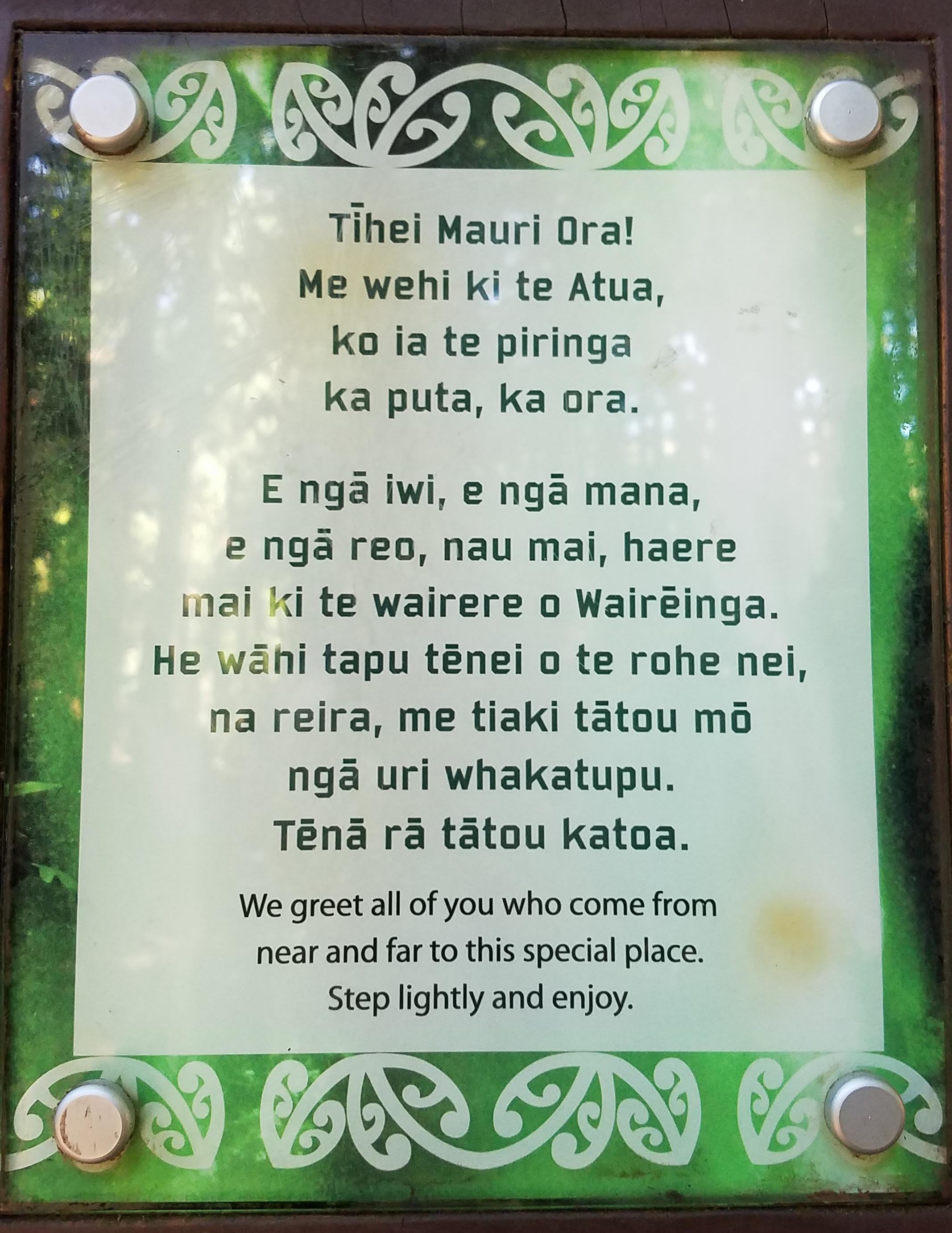

A warm Maori welcome to the falls

“Hey, missionaries!” they called, coming toward us to introduce themselves as BYU students who were taking a semester off to travel. (We love the way our name tags provide strangers with an excuse to strike up a conversation.) The couple—newlyweds, if no longer honeymooners—told us to look for another pair of Latter-day Saints they had passed on the track (which is the Kiwi term for a trail). “They’re an older couple from Australia; he’s the one carrying the big camera,” they explained.

We had not been long on the track before we encountered the man with the big camera. His wife had passed us a minute earlier, but she didn’t stop to talk because (as her husband indelicately explained) she was in too much of a hurry to find a toilet. They were from Brisbane, on holiday, and he, at least, was eager to talk, asking about our missionary assignment in Hamilton, and freely sharing his feelings about the 2009 closing of the Church College of New Zealand, a secondary boarding school that had been located on the site of what is now the Matthew Cowley Pacific Church History Centre. We had understood from Barry (who attended CCNZ in his youth), that the Church had decided to close the school not only because its 65-year-old buildings would need too much renovation to meet current standards, but also because New Zealand’s public secondary school system had progressed enough since the 1950s that a Church-run educational institution was no longer needed. The man from Brisbane, however, offered a different opinion. Many people were relieved to hear that CCNZ had closed, he said, because the school had developed a reputation as the place where frustrated parents sent rebellious children to “sort it out.” Whether this is true, we cannot say. What we can say is that we are learning that Aussies and Kiwis are not at all hesitant to share their opinions of the other.

The lazy river along the track

Once the man with the big camera had gone on to catch up with his wife, we continued along the serene path that follows the river to the falls. For most of the pleasant ten-minute walk, the river seemed more like a small, lazy stream, silently flowing under the palms and ferns. Suddenly the trail opened up, and there was the waterfall, dropping 180 feet over a rocky cliff. Nothing in the terrain up to there had betrayed the fact that such a steep drop-off was looming; we hadn’t even been able to hear water spilling over the edge and into the pool below.

“Leaping Waters”

The view from the top of the falls was fulfilling enough that we didn’t feel the need to climb down several dozen stairs to the pool, so we retraced our steps through the shady bush to the parking area. There we saw a sign that we hadn’t noticed earlier, distracted as we had been by conversations with other visitors. The sign indicated that what Fodor had called “Bridal Veil Falls” is known locally by its Maori name: Waireinga (Leaping Waters). The people who have inhabited this land for centuries believe that wairua (spirits) can effortlessly leap the height of the falls, and that the surrounding bush shelters patupaiarehe (fairies) who act as the area’s guardians. We didn’t see any fairies, but we are glad that someone has been caring for and protecting the natural beauties we did see on our first Sunday afternoon drive.

Leave A Comment