We were startled awake by the alarm at 4:30 a.m., although it didn’t seem that early because the sun was already up. We hurried to finish packing because we had to put our luggage outside our door by 5:30 for the porters to pick up, and then be downstairs, ready to leave the hotel at 6:00 so we could catch an 8:40 a.m. flight to Stockholm. The hotel provided us with breakfast bags containing little bottles of juice, an apple and an orange, a couple of pastries, and a sandwich. Michael still has a limited notion of what foods may be eaten for breakfast, and a ham and cheese sandwich garnished with peppers and tomatoes is not on his list. Fortunately, he had enough Czech koruna left in his pocket that when we got to the airport, he could buy a croissant and a “chocolate gourmandie” (a deluxe chocolate croissant). Because he believes that chocolate is one of those things that can and should be eaten whenever you want, Michael’s list of items that may be eaten for breakfast includes chocolate in any form. Ironically, Nancy’s breakfast list (which is expansive enough to include cold pizza) generally limits chocolate to the hot, drinkable kind—and only when the room temperature is low enough to warrant it. This morning she was more than satisfied with her sandwich, fruit, and cheese-filled pastries.

American ambassador’s residence

Eva was at the microphone once again during our drive to the airport, pointing out places of interest in less ancient sectors of Prague. Nancy was ecstatic to learn that we would be driving past the American ambassador’s residence because she had recently finished reading a book about its history. Norman Eisen, a former U.S. ambassador to the Czech Republic, tells the fascinating story in The Last Palace: Europe’s Turbulent Century in Five Lives and One Legendary House. Designed and built in the 1920s by Otto Petschek, part of a prominent Jewish banking family who also made a fortune in coal, the mansion was an extravagant expression of Otto’s artistic and scientific passions. Its construction nearly bankrupted the family, who lived there only a few years before the growing Nazi threat forced them to flee Europe. Originally known as Petschek Palace, the house was occupied in turn by a German general who appreciated its beauties and did his best to secure them; briefly by Soviet soldiers, who did their best to loot the treasures the Petscheks had left behind; and then by a series of American ambassadors—including Shirley Temple Black—who, like the German general, saw the cultural value of the estate and worked to preserve it while they also worked to preserve good relations with the Czech government and its commitment to democratic ideals, especially while the country was under Communist domination.

Checking in at the Prague airport

We made it to the airport in plenty of time for our flight. In fact, we had to wait 20 minutes or so before we were allowed to even check in. Previous observations had led us to suspect that Czechs are not driven by efficiency, and the airport check-in process only confirmed our suspicions. Two agents were available at the SAS check-in counter, but they were taking more than five minutes with each individual or couple, and there were more than a hundred people waiting in line to get on this flight. With only 90 minutes before departure, the math was not in anyone’s favor. We finished at the counter about 45 minutes before departure, but there were still about fifty people in line behind us. Some breakthrough must have occurred, however, because the plane filled up and we left on time.

Allison and Mike

The flight crew was definitely more efficient than the people on the ground—probably because the air crew was Swedish. Our group was seated together at the back of the plane, a convenient location because when we landed in Stockholm a couple of hours later, we disembarked through the aft door, down some stairs, and into a bus which took us to the terminal. Because we had again flown from one EU country to another, we did not have to pass through passport control or customs; our passports still show no evidence that we have been to either the Czech Republic or Sweden. Once we collected our bags, we went to the waiting area and were greeted by our friends Mike and Allison, who had arrived in Stockholm only an hour or so before we did. They had decided to forego the Prague trip because they had been there before, but are joining us for the cruise.

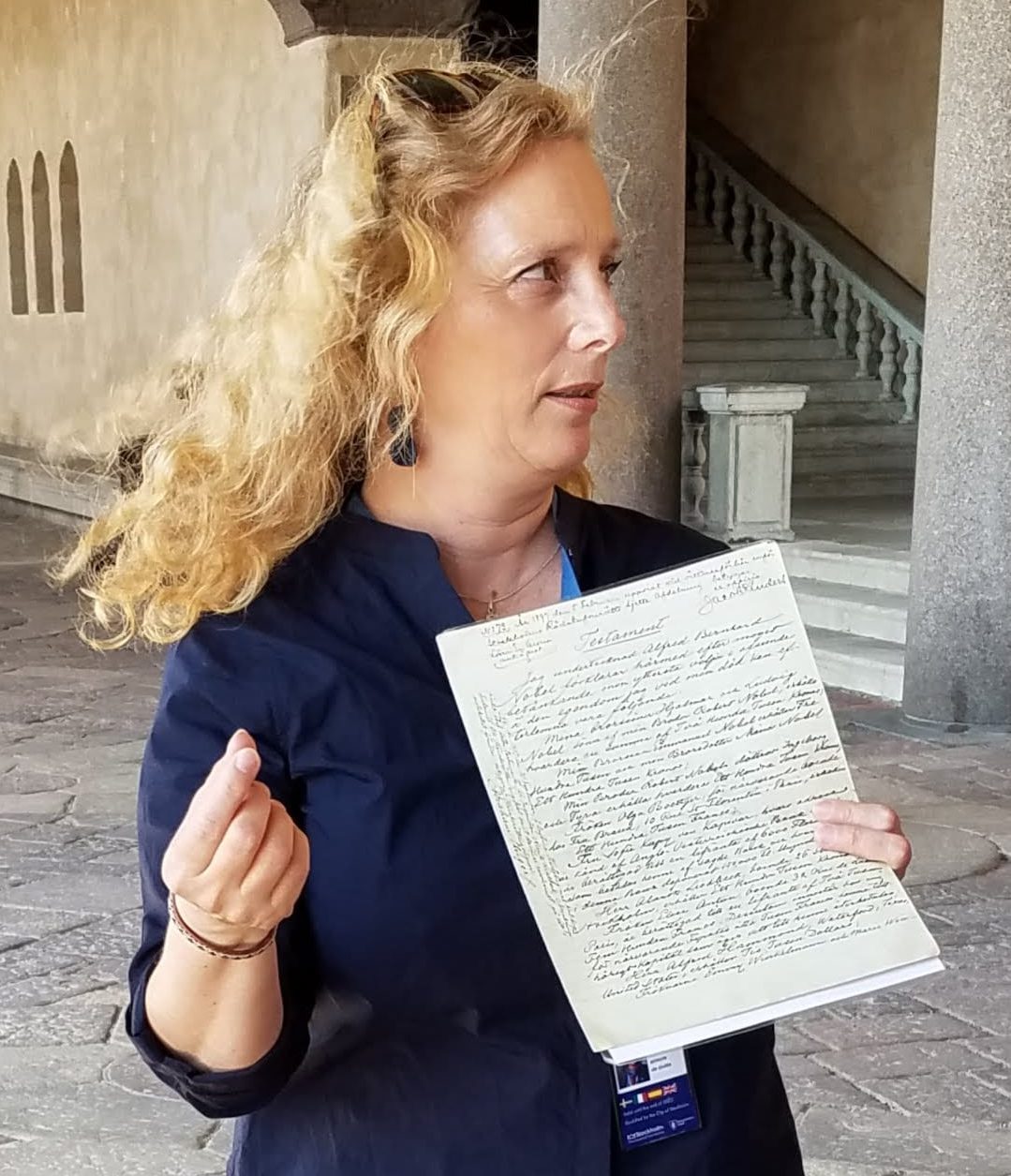

Our Swedish guide, Simona, with a copy of Stockholm’s original city charter

It was too early to check into our hotel, so Carol had arranged for a bus to meet us at the airport for a tour of the city. One of the first things our guide, Simona, told us was that the wearing of seat belts is mandatory in Sweden, even on buses, so we all buckled up. Other introductory facts: Sweden’s land mass is slightly larger than California’s but its population is less than one-third that of our Left Coast state, so most of Sweden remains undeveloped and unspoiled. Minimum income tax is 30% but may be as high as 51% if your income is greater than $5000/month. It used to be even worse for the wealthy, Simona said. Before 1991, when a cap was placed on taxable income, tax rates could exceed 90%. For example, in 1976 Astrid Lindgren, the creator of Pippi Longstocking, was assessed 102% because she was classified both as a wage earner and as a corporate employer. But those high tax rates provide an array of social services, including free education, free health care, 18 months of paid maternity leave, and subsidized utilities. Simona also told us that because yesterday was Sweden’s National Day, today is what locals call a “squeeze day” (one that falls between a holiday and the weekend). That means that the populace is out enjoying time off in beautiful weather—and creating more congestion in public spaces.

The park on Lake Mälaren behind City Hall

Stockholm City Hall

The entrance to City Hall is flanked by a relief of ancient Stockholm

… and one of modern Stockholm

Our first stop was the Stadhus (City Hall), built on the edge of Lake Mälaren, an island-studded body of freshwater that eventually flows into the Baltic Sea. Stockholm was founded on a small island at this confluence in 1252 A.D. and now occupies many surrounding islands as well as part of the mainland. Michael had never thought of Stockholm as one of Europe’s great ports, but shipping and boat building have been its mainstay industries for centuries.

Parliament House

Crossing a couple of short bridges, we reached Gamla Stan, Stockholm’s Old City. The bus took us past the Riksdagshuset (Parliament House), where 16 year-old Greta Thunberg continues to lead student protests every Friday, hoping to motivate adults in power to do something about the world climate crisis. (Today is Friday; did we miss her? We saw several “Save the Planet” banners in the vicinity, but no protesters.) Outside Parliament, Simona led us off the bus and down the narrowest street in Stockholm to Gamla Stan’s main square, pointing out helpful landmarks along the way. She then suggested that we fan out for lunch and meet her back at the same spot about 1:45 p.m.

Lunch at Fem Små Hus

Weekday lunch menu

There were many choices for lunch in this quaint tourist mecca, but for some reason most of them seemed to specialize in Italian food. In company with Mark and Lynn, we walked up a side street and found a restaurant that offered a menu with something besides pizza and pasta, and found an empty table outside. (No smokers today.) Nancy ordered a bowl of vichyssoise (potato and leek soup) and a plate of cold asparagus with pesto. Michael wasn’t sure exactly what type of fish he would get if he ordered the “fried witch with potatoes” but decided to take a chance; it turned out to be some kind of flounder and was quite good.

Royal Palace

Palace guard

When the whole group gathered again after lunch, Simona took us to the Royal Palace, where we caught the tail end of the 2:00 changing of the guard. Like most monarchies, the origins of Sweden’s earliest kings are murky, but an important ruling dynasty was established in 1523 when Gustav Vasa, who had led a rebellion against the king of Denmark, was elected king by the Estates of the Realm, Christian Europe’s version of the E.U. during that period. Gustav then leveraged popular sentiment toward Protestantism to wrest property held by the Roman Catholic Church in Sweden from papal control. Thus began the Stormaktstiden Sverige (Age of Swedish Greatness), a period when Sweden dominated the Baltic region both politically and economically.

Karl XIV Johan, aka Jean-Baptiste Jules Bernadotte

One of Gustav’s successors, Charles XII, became a popular hero at the age of eighteen when his small but capable army managed to defeat a much larger Russian force in 1700, forcing Peter the Great into submission. When Charles XII died, unmarried and childless, while leading his army into Norway, the throne passed to his sister, who had little interest in governing and thus didn’t resist when the Riksdag (Parliament) proposed a power-sharing agreement that ended the royal family’s absolute rule—and the Stormaktstiden Sverige. By 1810 legitimate heirs to the throne had died out, but although the monarchy was now more ceremonial that functional, it still seemed necessary to have a royal at the head of government; therefore, the Riksdag chose a French nobleman, one of Napoleon’s marshals, to become king. We’re not sure what qualified Jean-Baptiste Jules Bernadotte (regnal name: Karl XIV Johan) to lead the country, but the Swedes must have been satisfied with him because his descendants still reign even if they don’t rule. Simona told us that each citizen pays about $3 per year in taxes to support the royal family, and nobody seems to mind.

Current Swedish royal family

The current royals, King Carl XVI Gustav and his wife, Silvia, actually live in Drogningham Palace outside Stockholm, so the 1400-room Royal Palace we saw this afternoon is used primarily for official gatherings. Because the Swedish crown passes to the first child regardless of sex, Crown Princess Victoria is next in the line of succession; her oldest child is a girl, so the country can look forward to years of female reign after Carl Gustav passes.

The Iron Boy

Once we had viewed the larger-than-life equestrian statues of Charles XII and Karl XIV Johan that stand outside the Royal Palace, Simona wanted to show us another statue, located in the shady courtyard of a church not far away. The Iron Boy, created by sculptor Liss Ericksson and installed here in 1967, is tiny by any standard—less than six inches tall—but especially when compared to all the monuments to kings and saints that we’ve seen elsewhere. Simona explained that the Iron Boy represents a needy child, and that providing him with gifts is supposed to bring good luck. Stockholm’s citizens and visitors thus have adopted the little statue, leaving coins, trinkets, and clothing. Today, in the wake of National Day, someone has decorated Iron Boy in patriotic blue and yellow.

Gossip mirror

Leading us back toward the center of Old Town (which, as in Prague, is mostly closed to vehicle traffic), Simona stopped and pointed to some small curved fixtures jutting out between the windows on the upper floor of an eighteenth-century residential building.

“Those are ‘gossip mirrors,’” she said. “They’re like the rear-view mirror in a car, except instead of showing what’s behind you, they allow you to see into your neighbors’ windows—so you’ll have more to gossip about, you see.”

Delicious, cool water is available from public fountains

Near the end of the afternoon, we met our bus on a street on the perimeter of Old Town where vehicles are permitted, gathered our suitcases, and lugged them a couple of blocks up the hill to the Lady Hamilton Hotel.

NJ and Mary-Anne

As we lined up to get our room keys, NJ and Mary-Anne came down the stairs to greet us. The last of the eleven couples in our group of friends, they had arrived in Stockholm and checked into the hotel earlier this afternoon. We were now complete!

Outside the Lady Hamilton Hotel

A model galleon hangs in the stairwell

Collection of horse scooters hanging from the ceiling

Our small and very warm room

The Lady Hamilton belongs to a trio of hotels in Gamla Stan known as the Collector’s Group, established by a man who liked to collect antiques with a maritime theme. This one is named after an eighteenth-century British actress who was the mistress of Lord Nelson, the famed British admiral and the namesake of one of the other Collector’s hotels. Presumably, all three are as cluttered with nautical knickknacks and period paraphernalia as this one.

Our quaintly decorated room has barely enough space to accommodate two suitcases next to the double bed, and we have to climb over one of them to get into the bathroom. We figure that we can bear the inconvenience for one night, but a worse problem is the temperature. It’s been an unusually warm day in Stockholm, and even setting an electric fan in the open window has done little to cool off the room. We hope we’ll be able to sleep tonight. Usually, one can expect some relief from the day’s heat after the sun goes down, but consider this: we’re north of the 60th parallel, only two weeks before the summer solstice, so the sun is unlikely to set here until after 10 p.m.—and it will be back up by 3:30 tomorrow morning.

Nobel Museum in Old Town

St. George conquering yet another dragon, this one in an Old Town square

No more group activities had been scheduled once we had been received by Lady Hamilton, so since our room did not provide a very comfortable place to relax, we decided to go out exploring for a while before dinner.

Earlier in the day we had noticed posters advertising an Early Music Festival taking place this weekend in various venues around Stockholm, but we didn’t pay much attention because we didn’t think we’d have a chance to attend any of them.

Inside the Finnish Church, which used to be a racquetball court

However, as we headed toward the waterfront, we noticed a crowd gathering outside the Finska Kyrken (Finnish Church) close to where we had seen Iron Boy. A sign posted nearby indicated that a performance of “Swedish Folk-Baroque Hits” by the Silfver Trio (whoever they were) was scheduled to begin at 6:00—only twenty minutes later. Tickets were still available, but we had an 8:00 dinner reservation. Would we have time to attend the performance? The ticket seller assured us that the concert would last only an hour, so now the only thing preventing us from purchasing a pair of seats was that we had no Swedish kronor nor even any euros, and the vendor couldn’t accept credit cards. When we explained our situation and asked where we could find an ATM, the seller told us that the closest one was about a ten-minute walk away.

“You won’t be able to get there and back before the concert begins,” she said, “so just take the tickets and you can pay afterward.” We thanked her for trusting us and went inside.

Silfver Trio

The Silfver Trio included a violin, a viola de gamba, and an instrument we’d never seen before: a small guitar-shaped sound box attached to long, stringed neck with a bunch of metal keys down the side. As we were discussing what it could be before the performance began, the man sitting next to Nancy reached over, smartphone in hand.

Nyckelharpa

“Forgive me,” he said, showing us the screen, “but I couldn’t help overhearing your question about the instrument. In Swedish, it’s called a nyckelharpa, but I didn’t know the word in English so I looked it up for you.”

The website he had found called it a “keyed harp” or “key fiddle.” The traditional Swedish instrument is bowed like a violin, but the player changes pitches by pushing levers to depress the strings rather than using direct finger contact. The performers—two men and a woman, all probably fifty or older—played very well, and we enjoyed a relaxing hour listening to the music, but both of us agreed that another hour might have become tedious. If the Silfvan Trio’s repertoire is typical, Swedish folk music isn’t much like the Celtic music we love; tonight there was no bodhran to set our feet tapping, no invitation to join in clapping, and the most rousing piece on the program was less like a lively Irish jig than a sedate ballad.

Stortorget public square

Narrowest street in Stockholm

After the concert, we found the ATM and returned to the church with our cash just as they were closing up. We made another circuit through Old Town, then headed to the Kryp In (Swedish for Cubbyhole) for dinner. Michael had read about the restaurant online, and when we asked the concierge at the hotel whether she could get us reservations, her face lit up with a big grin. “That’s my favorite restaurant not only in Old Town, but in all of Stockholm!” she said. She made the reservation, and we were lucky enough to get a table outside, where there was a nice breeze.

Kryp In

Reindeer

Scallops

Nancy had the fixed-price menu which included cream of cauliflower soup, followed by fillet of reindeer with mashed potatoes and onion-rhubarb compote. (In case you’re wondering, domesticated reindeer, like domesticated bison, tastes pretty much like beef.) Michael also started with the cauliflower soup, but for his main course ordered scallops with orange and pickled tomatoes on a bed of arugula and crispy bacon. Chocolate mousse was included with Nancy’s meal, but what she really wanted for dessert was the white chocolate panna cotta with berry sauce, so Michael ordered that and we traded. Everything was delicious.

By the time we got back to the hotel, our room had cooled down, which was good because the fan was loud and screechy—not the kind of white noise that would lull us to sleep. However, we still had to keep the window open, which was not good because other tourists continued to revel loudly in the street below until after 11:00 pm. And, with or without the window open, we could hear church bells bonging every fifteen minutes. Michael remembers hearing them strike at 11:45, but not again until 4:00, so he must have gotten a few hours’ sleep. As is typical for Nancy, neither the revelers nor the bells kept her from falling into undisturbed sleep before midnight.

Makes me rather homesick. Some of my ancestors helped build the German Church in Gamla Stan. One of my favorite memories is a Christmas Eve mass in Stor Kyrkan while I was missionarying. Another was a faux Nobel Dinner in City Hall while attending a law firm meeting. Reindeer us much better than beef.