Getting ready to begin today’s activities involved trying to keep water within a minuscule shower whose sliding doors did not quite meet at the edges, avoiding bumps on the head and left elbow from the sloped ceiling over the sink, and wondering whether the cool fog outside the window was any less dense than the warm fog inside our room.

In the dining room downstairs, Michael passed up scrambled eggs that had been left out too long on an unheated plate, and instead picked up some boiled eggs from a bowl that the server had just brought from the kitchen. (A little too soft for his taste, but at least they were hot.) Nancy had some yogurt and fruit, but both of us consumed most of our calories in the form of baked goods. The most significant difference between the breakfast buffet at the Hotel Ry and its counterpart at a typical American hotel is that although in either case the pastries look good, here they actually taste good. Really good! Danish bakers obviously understand that vegetable shortening is not an acceptable substitute for real butter. As we picked stray pastry flakes from our plates and licked raspberry jam off our fingers, we watched people in business dress–Rotarians, no doubt–struggle to open the lobby doors against the wind while burdened with briefcases, notebooks, and easel pads.

A Christmas tree farm in the Søhøjlandet

View of Julsø from the village of Laven

Rain beat on the windshield of our Peugeot nearly all day, making the Søhøjlandet’s scenic routes a little less picture-perfect, but the drive was worthwhile nevertheless. We would have taken more photos, but the narrow, winding roads didn’t grant many safe places to pull over, even for a few moments. At one point we turned around to take advantage of a parking spot in front of an empty commercial building in the village of Laven, where a terrace overlooking the street also offered a good view of Julsø (another lake). When Nancy climbed the stairs to the terrace, she saw scorched signs indicating that the upper floor had once been a dance club, now closed after a fire. Determined to get a good photo from the balcony, she crossed the charred wooden floorboards with the utmost care to avoid falling through.

Sejs-Svejbæk Kirke

Our first scheduled stop this morning was at the cemetery of Sejs-Svejbæk Kirke, which serves two parishes northwest of Ry. The commuter train runs through here, too. While we were waiting at a crossing for it to go by, we could hear children chattering in a nearby schoolyard–the first such sounds we’ve heard during our stay in Denmark. When we reached the cemetery, we were disappointed to see a large, modern church next to it–certainly not what would have been standing when Nancy’s third-great-grandmother was interred here in 1824. Nevertheless, Nancy ran through the rain to the back of the memorial park just in case a stone bearing the name of Zidsel Lauritsdatter Benner might be extant among the discards, but the dates on even the oldest stones didn’t reach beyond the early twentieth century.

Silkeborg

Silkeborg

We drove through Silkeborg, the Søhøjlandet’s largest town, which manages to look quaint despite the presence of some big resort hotels and spas. South of Silkeborg, the narrow road climbs from the lakes into the highlands, where groves shimmering with silvery lindens gradually give way to forests of evergreens. We had driven through pine trees for probably fifteen minutes before we noticed that most of them were rather evenly spaced. Farther on, couple of dirt roads rutted with big tire tracks confirmed that we were on land devoted to Denmark’s sustainable lumber industry.

Another fifteen or twenty minutes took us out of the forest and back among cultivated fields, but the road never got any wider, and when we got caught behind a big construction vehicle there simply was no way around it until our routes finally diverged at a crossroads.

Windmills still supply power to the countryside, but they don’t look as quaint as they used to

Danish cattle are shaggier than those we’ve seen in the western U.S.

By now we were nearing Klovborg, the parish in which Zidsel Lauritsdatter had been born, and where she and Johan Conrad Christiansen Benner had been married in 1792. (Why Johan had traveled nearly two hundred kilometers from his ancestral home on the island of Ærø and spent the rest of his life in the farm country of Jutland is a question we cannot answer.)

Klovborg Kirke

Klovborg Kirke was easy to spot across the fields, some bright yellow with mustard and others brown with drying cornstalks, next to a stand of tall pine trees. As we entered the little church, we could hear the hum of a vacuum cleaner. The caretakers, a middle-aged husband and wife, interrupted their work to show us some of the church’s distinctive features and use their limited English to tell us about its history.

Looking toward the altar in Klovborg Kirke

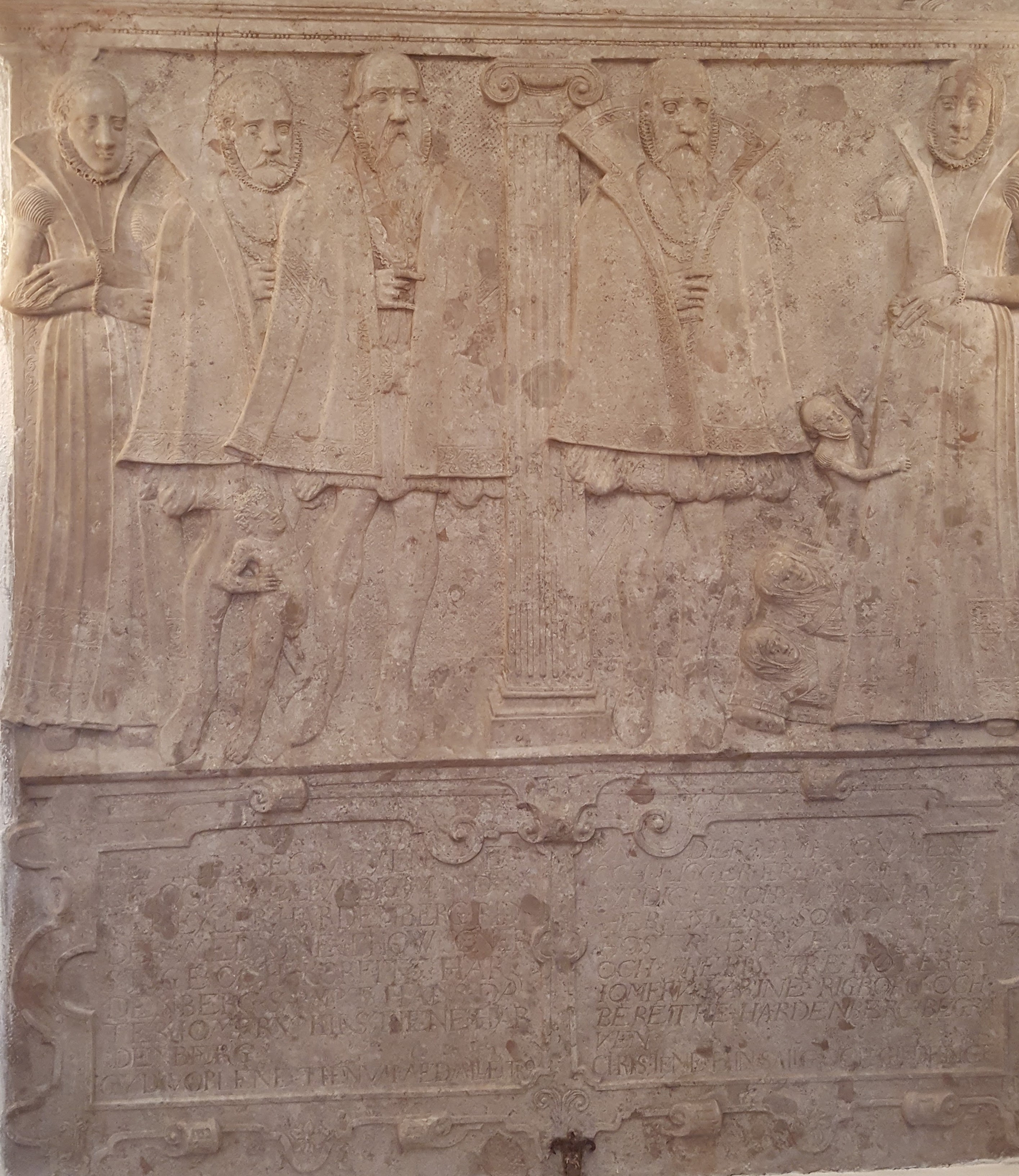

The 16th-century Hardenberg memorial shows family members mourning two deceased children

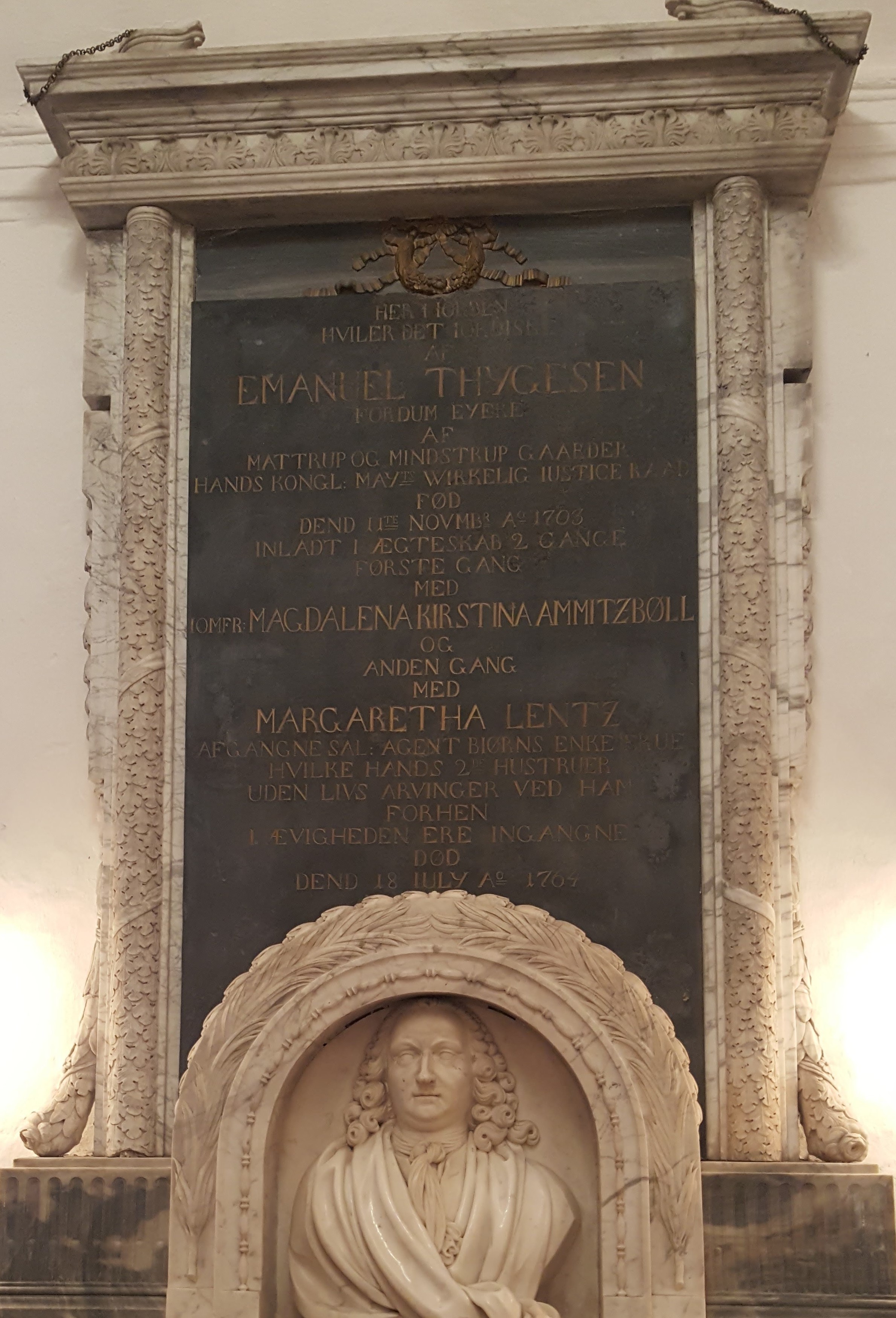

Another crypt in Klovborg Kirke honors patron Emanuel Thygesen, who died in 1764

The front pew in Klovborg Kirke bears the crest of patron Erik Hardenberg, dated 1591

While Nancy was taking photos, Michael walked outside. A few minutes later, he came back to report that a small outbuilding on the grounds contained a restroom. Deciding that she, too, should take advantage of nearby facilities while she had the chance, Nancy walked across the churchyard and opened the nearest door. A toilet and sink were visible through another door just inside, but only after she had shut that door behind her did she notice toothbrushes, shaving equipment, and a shampoo bottle on a shelf next to a bathtub. Evidently this was not a public restroom. Indeed, when she came out of the bathroom, Nancy could see a kitchen at the other end of the entrance hall. A couple of coffee cups on the table and plates strewn with crumbs made her wince as she realized that she had just invaded the private residence of the caretakers who had been so kind to them inside the church.

“You didn’t tell me the restroom you had found was in the caretakers’ house!” she chided when she and Michael returned to the car.

“What do you mean?” he asked. “The restroom looked public to me.”

“Didn’t you notice the toothbrushes and stuff by the bathtub? And the kitchen down the hall?” said Nancy.

“I didn’t see any toothbrushes, or a bathtub. Which door did you go in?” Michael asked.

“The one just across from the church entrance. Was there another one?”

“Yes. The public restroom was on the other side.”

“Oops,” said Nancy. “Well, too late now.”

Hammer Kirke

Hammer Kirke’s bell hangs in a wooden shed on stilts

Our next stop, Hammer Kirke, was only about ten minutes from Klovborg. Johan and Zidsel Benner must have taken up residence in Hammer parish shortly after their marriage, because it was here that their son Lauritz (Nancy’s great-great-grandfather) was born in 1794. The church was locked, so after taking a couple of exterior photos we moved on to Sindbjerg, another parish about 15 km farther south.

Sindbjerg Kirke

Sindbjerg is located in the valley between the Guden and Grejs Rivers. This valley was the home of Anna Margreta Sørensdatter (Nancy’s great-great-grandmother) and her family. Anna’s parents and maternal grandparents were married in Sindbjerg Kirke (in 1796 and 1764, respectively). In 1816, Anna, too, knelt at the altar in Sindbjerg and was married to Lauritz Johansen. (For some reason, Lauritz preferred to use his patronymic rather than the Benner surname.)

According to local legend, when the dilapidated medieval-era church in nearby Grejs was demolished and replaced with a larger one in the 1880s, the people of Sindbjerg–then part of the same parish–demanded that their church get a similar update. What they got was the addition of a disproportionately large tower, constructed of the same red brick that had been used in Grej.

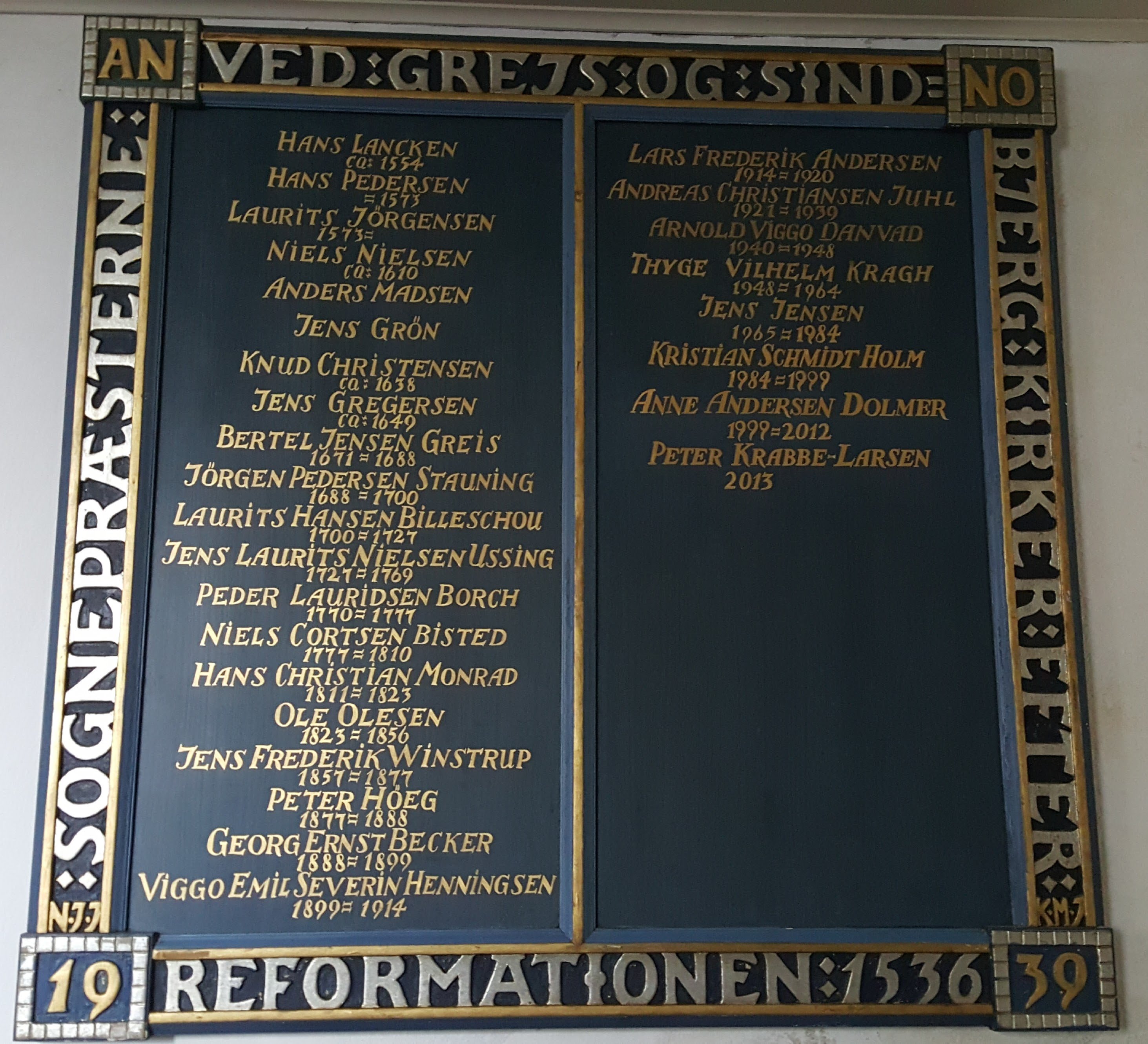

Most Danish churches feature a plaque listing every priest who served the parish. Sindbjerg’s list starts in 1554

Looking toward the choir loft in Sindbjerg Kirke

Well-preserved medieval frescoes decorate the vault above the altar in Sindbjerg Kirke

The current altarpiece showing Christ in Gethsemane dates from 1868

These gilt figures were part of an older altar where Nancy’s ancestors knelt when they made their wedding vows in Sindbjerg Kirke

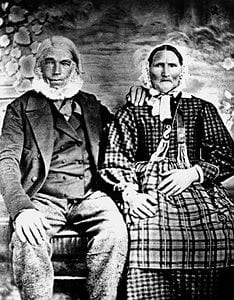

Lauritz (Lars) Johansen and his wife Anna Margreta Sørensdatter, Nancy’s great-great-grandparents

After their marriage, Lauritz and Anna Johansen settled in the Grejs Valley, just south of Sindbjerg. They had ten children, seven of whom lived to adulthood. The oldest of the surviving children was Nancy’s great-grandfather, Søren, who worked both as a farmer and as a carpenter. Lauritz trained two of his younger sons to become tailors. They left Jutland in the late 1840s for Copenhagen, where they did military service making uniforms for the troops. It was in Copenhagen that these brothers encountered the first Latter-day Saint missionaries sent to Denmark during the summer of 1850, and they were some of the first Danes to be baptized by the Mormon elders. Lauritz, Anna, and their other children also listened to LDS missionaries who traveled to the Grejs area. Within the next two years the entire family had converted to this new religion, and endured a great deal of persecution as a result. In 1854, most of the family–including Søren–left Denmark to gather with other Latter-day Saints in America. (Once there, Lauritz began to use the name Lars, so all his children took Larsen as their American surname.) Two of the Larsen brothers, Johan and Christian Johan, remained in Denmark for another year or more so that they could complete the missionary work to which they had been called. It was one of these who went north to Stårup and helped to convert Niels and Maren Bertelsen, whose daughter Stena eventually would become the second wife of Søren Larsen.

These gilt figures were part of an older altar where Nancy’s ancestors knelt when they made their wedding vows in Sindbjerg Kirke

Vindelev Kro

The Grejs River had been the source of power for the mill at Hopballe, now the farm-to-table restaurant where we had lunch on our first day in Denmark. Other villages in the valley that appear in Nancy’s family history records include Flojstrup, Holtum, and Vindelev. Today, none of these locales is much more than handful of homes clustered along a country road, although Vindelev has its own church and an inn. Several weeks ago, Nancy had found a website for Vindelev Kro indicating that the inn served meals and contained a gallery featuring the work of local artists. It looked like the perfect place to have lunch today–except that, according to the website (which consists only of a home page), the inn and gallery generally are open only by appointment. The website gave a phone number, but no email address. Because Nancy wasn’t keen on making an international call to someone she didn’t know who probably did not speak much English, she didn’t try to phone ahead and just hoped that maybe the place would be open. It wasn’t.

A picturesque thatched house in Holtum. Note the long pennant flying from the pole next to the tree at left. We’ve seen the Danish national flag displayed in this form in many places

An ancient Romanesque church in Grejs was demolished and replaced by this large brick structure in the 1880s, at least 25 years after the Larsen family left Denmark. Three Larsen children who died before the family emigrated to America were buried in the churchyard

The organ in Grejs Kirke

The baptistry in Grej Kirke dates from the 12th century and is undoubtedly where Søren Larsen was christened in 1822

The decorative painting on the ceiling in Grejs Kirke is similar to that found in some pioneer-era LDS churches in Utah

The pasta and pizza at Marcello’s Ristorante were not outstanding, but satisfied our needs

Grejs Kirke was the last of our family heritage stops before we drove into Vejle, the county seat and largest city in the vicinity, in search of lunch. We missed the first highway exit where we probably could have found some fast-food restaurants; the exit took us into the center of town, which made locating somewhere to get a quick meal a little more challenging. We passed several restaurants in the theatre district that were open only for dinner, but finally we located a shopping mall with available parking and figured that it probably contained some casual dining options. Just inside the entrance was an Italian buffet that offered just what we needed: adequate food and quick service.

We wanted to eat and get on our way as soon as we could so that we would have as much time as possible at Koldinghus, located about half an hour away. Once a fortress and royal residence, this imposing structure overlooking a lake at the west end of Koldingfjord is now a museum filled with an eclectic collection of historical and cultural artifacts from many centuries. We hung our dripping raincoats on a rack in the entrance hall, but probably should have kept them with us because it was still raining steadily and the self-guided tour kept directing us to more galleries across the open courtyard.

A fire in 1808 reduced Koldinghus to ruins. The restored castle reopened as a museum in 1989. (The lighter stone is original; darker portions are replacements)

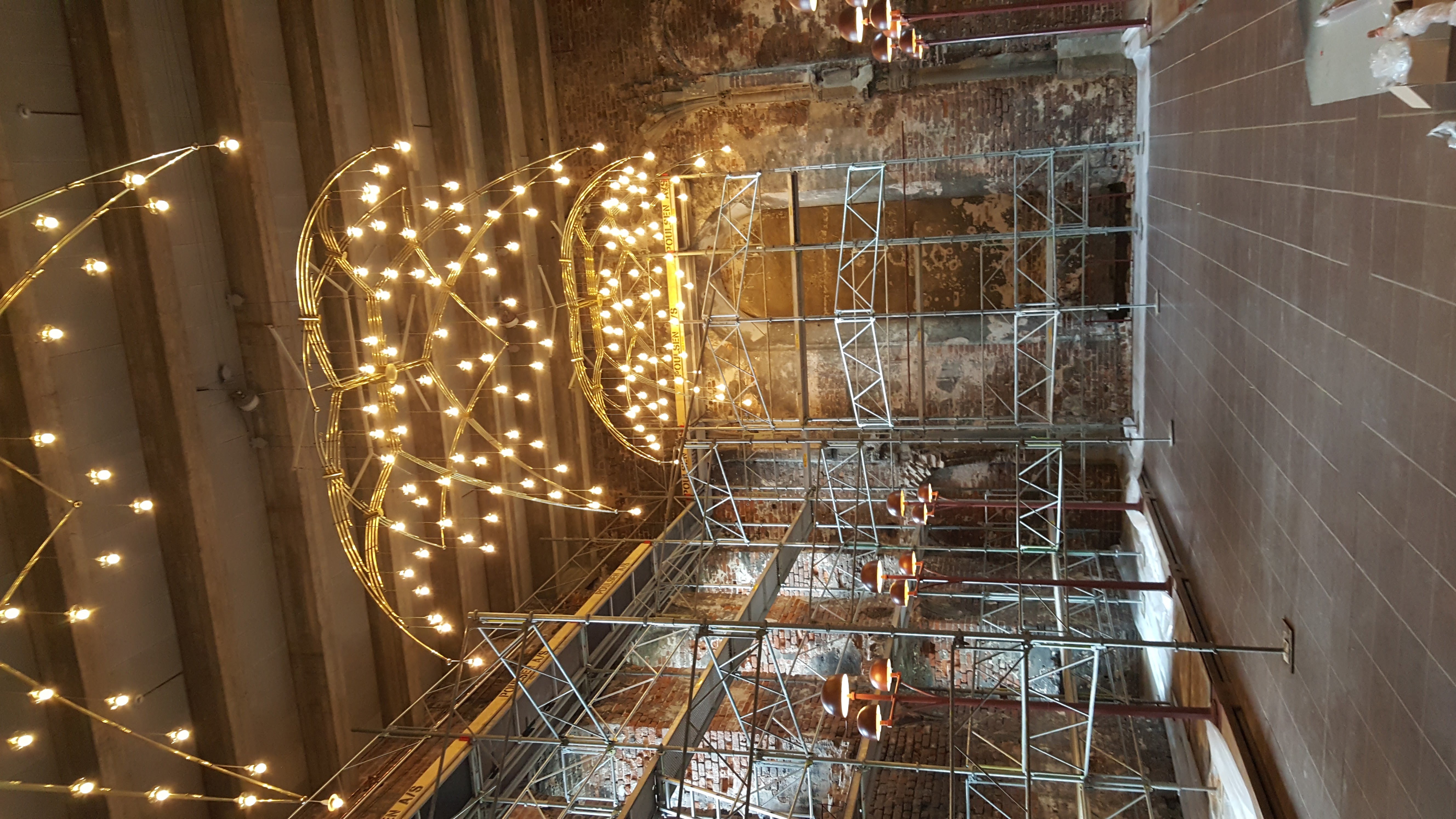

The Ruin Hall inside Koldinghus is used for special exhibitions

Koldinghus Chapel, currently under renovation

Koldinghus courtyard, viewed from the Trumpeter’s Tower

View of Kolding from the Giant Tower (158 steps up from the ground)

The Great Hall in Koldinghus is the second longest in all of Europe

A trompe l’oeil wall painting makes an interior room in Koldinghus look twice as large as it is

A 16th-century map of Denmark

King Christian III and Queen Dorothea

Koldinghus had been built by King Erik V in 1268 as a military fortress, but after the development of better long-range weaponry made the castle obsolete for defensive purposes, later monarchs turned it into a luxurious residence. Among these was Christian III, who reigned during the sixteenth century and was responsible for converting Denmark from a Catholic nation to a Protestant one; his wife, Dorothea, is noted for establishing a hospital, a school, and a mill in Kolding to improve the lot of the poor.

The extensive silver collection at Koldinghus includes this elaborate 18th-century set belonging to Queen Caroline Mathildes

. . . as well as this 20th-century set designed by Hans Hansen

The scope of the various artifacts on display at Koldinghus is overwhelming: everything from antique tapestries to a 1930s model train set. We also walked through a special exhibition in the Ruin Hall called “Beyond Icons,” in which graduating students from Design School Kolding explained the aesthetic and cultural significance of common objects such as Lego bricks and paper clips.

It would have taken several more hours to see everything at Koldinghus, but we needed to leave by 4:30 p.m because we had a dinner appointment on the island of Als at 6:00. Tonight we were not going to eat at a restaurant; rather, we had been invited to dine at the home of Elli A., the second-cousin-once-removed of Nancy’s friend Kirsten. Kirsten and her family have maintained close ties with Elli, making fairly frequent trips back and forth across the Atlantic to visit one another. When Nancy told Kirsten that we were planning a trip to Denmark and asked if she had any friends or relatives we might visit, Kirsten immediately mentioned Elli. “She’s so wonderful! I’m sure she’d enjoy meeting you, too,” she said. “And she speaks impeccable English.” So, for the past couple of months, Nancy, Kirsten, and Elli have been exchanging emails, making arrangements for our visit. We were excited to meet a “real” Danish person not connected to the tourist industry.

The island of Als where Elli lives is at the southeast end of Jutland, separated from the peninsula only by a narrow arm of Alsfjord.On the other side of the fjord is Ærø, the island that Nancy’s third-great-grandfather Johan Benner came from. We had hoped to visit Ærø today, but since the only access to the island is by a ferry that makes the run only a few times a day, we decided that we’d have to save Ærø for another trip. That turned out to be a wise decision. Because Ærø is known mostly for its beaches, boating, and bike paths, sightseeing there on such a wet, dreary day probably would not have been very pleasant.

Danfoss Universe, a science-oriented theme park on the island of Als

The city of Sønderborg straddles the strait between Jutland and Als. We stopped there briefly to fill up the gas tank and and buy some flowers to take to Elli. Driving from Sønderborg to Havnbjerg, the town she lives in, seemed less like driving through Denmark than like driving through Cincinnati’s northern suburbs. We passed some impressive modern corporate campuses, including the global headquarters of Danfoss, which produces components for climate-control equipment, and Linak, another major company that makes electric components for various types of specialized machinery. We also passed an intriguing structure shaped like a giant puzzle piece across a large expanse of grass and parking lots. Signs said that the place was called Universe; we later learned that it is a science-oriented educational theme park sponsored by Danfoss.

Elli’s home in Havnbjerg is in a modest residential neighborhood, around the corner from a small shopping center that looks as though it could have been transplanted from any American suburb that has appeared within the past twenty years. In an email she had sent a week or so ago explaining how to find her house, Elli had apologized in advance for the “awful” condition of the property across the street, occupied by some “hillbillies.” We were amused that she had used that distinctly American term to describe her neighbors, but when we arrived we could see that Elli knew exactly what the epithet meant. On the opposite side of the road from Elli’s tidy home was a dull yellow house whose roof was missing some shingles. In front, an old car with mismatched fenders slouched on a gravel bed with so many random patches of tall grass poking up through it that we weren’t sure whether it was supposed to be a parking strip or a yard. At one side, a couple of trash bins buried beneath sagging cardboard boxes and household refuse leaned against a dilapidated shed. We’ve seen plenty of sites like this in the States, but here in Denmark it seemed wildly out of place.

Elli greeted us warmly when we rang her doorbell, ushering us into her cozy living room. We had expected this home to be filled with the same type of mid-century Danish teak furnishings that Nancy’s parents had favored, but Elli’s décor is more traditional. She spent many years as a flight attendant for charter airlines based in Denmark and later in Kenya, so the bric-a-brac in her heirloom cabinets and the artwork on her walls reflect her travels to exotic places. She is especially proud of a photo of three African lions, a close-up that she took herself without a telephoto lens.

Elli is widowed, so after she retired from the airlines she returned to Havnbjerg, the little community where she had grown up. Although she didn’t say so, we would guess that most of the farmland her family used to own on Als has been taken over by development since the rise of industries like Danfoss and Linak. She doesn’t have to milk cows or collect eggs anymore, but like most of her compatriots, Elli still relies on fresh food from local sources as much as possible. Tonight she served us chicken tenders in cream sauce over rice, fresh green beans with tomatoes that tasted like tomatoes should, and a delicious apple-hazelnut crisp made with fruit from trees in her own backyard. We really appreciated the home-cooked meal and the conversation. Elli told us about her family and her travels, and also answered a lot of our questions about contemporary Danish culture.

When we told Elli that we were amazed at how well rural communities all over Jutland had been able to maintain their ancient parish churches, she reminded us that since the Evangelical Lutheran Church is state-sponsored, it is the government that maintains the church buildings. “They’re supported by taxes, so they don’t have to depend on member donations like in America,” she explained. We had noted the lack of social halls, classrooms, and administrative space in these little churches, and speculated on how different typical religious practice in Lutheran Denmark must be from the multi-faceted, community-oriented worship, service, and socializing that goes on among Mormons in the U.S.

“Not many people here go to church regularly,” Elli told us. “Most people go to church only on holidays, if they go at all. They may get married in the church and have their babies christened there for tradition’s sake, but a lot of young couples don’t even bother to do that anymore.” Her remarks caused us to reflect on the fact that a century and a half ago, at least 14,000 Danes had demonstrated their religious conviction by converting to an unpopular faith, enduring persecution because of it, and then leaving everything familiar behind to emigrate to a foreign land where they could practice their new religion unmolested. (Today, even though the population of Denmark is probably five times what it was in 1860, there are fewer than 5,000 Latter-day Saints here.)

Elli and Nancy

About 8:30 p.m. we decided that we had better say mange tak (many thanks) and goodbye to Elli because we still had a thirty-minute drive back to Sønderborg, where we had reserved a room. We didn’t want to get to bed too late because tomorrow we have to be up and on our way early in order to get back to Hamburg in time to catch our train to Berlin–and we’re a little concerned about weekday-morning traffic over that one-lane bridge. We were about to pull out of Elli’s driveway when we realized that we hadn’t taken any pictures with her, so we rang the doorbell and spent another fifteen minutes trying to get a good shot in dim indoor light.

A couple of days ago, Nancy had received an email from the manager at Als Kloster, another former monastery turned into a bed-and-breakfast where we planned to stay tonight. She explained that the B&B has no front desk, so she provided instructions for getting into our room and a key code to unlock the door. Nancy searched her phone for that email message as we drove toward Sønderborg, but by the time we were halfway there, she still had not been able to locate the thread that contained the key code. Since neither of us has international data roaming service, and since the only manmade structures along this stretch of highway were those big corporate campuses, now dark and empty, we realized that we would have to return to Elli’s and ask to use her wifi.

Four or five teenage boys had gathered in the middle of the street near Elli’s house when we got back. The “hillbillies,” no doubt.

“This is really embarrassing,” we said when Elli opened her door to us once again. But she laughed when we explained our situation, and cheerfully turned on her laptop. It took another twenty minutes for us to access Nancy’s g-mail account and find the vital message–which inadvertently had been sent to her trash–and get back on our way.

When our GPS directions indicated that we were within one minute of our destination, we began to worry. We had turned off the highway and entered a neighborhood that looked like it had once been the back forty of someone’s farm, on which a few small houses and mobile homes had been set randomly down muddy driveways. We knew we were in trouble when we realized that the road had ended and we were driving into tall, wet grass, and the voice announced, “You have arrived.” The only things we could see in our headlights were the the rain and the bramble bushes from which a couple of scared rabbits had just emerged. From the map on our phone, however, we could see where Als Kloster was supposed to be–we just couldn’t see exactly how to get there. So we turned around and went back to the main road, hoping that somehow our way would become clearer.

“Look!” Nancy called out as we continued down the highway. “There’s a sign for a B&B!”

“Where? Where?” asked Michael from behind the wheel.

“Back there, at that driveway on the left we just passed. It was really small.”

The pavement ended at another left turn that led to small group of houses clustered around a gravel parking area. The buildings didn’t exactly look like a B&B, nor like the remnants of an old monastery. Through the window of one of them we could see someone watching TV–definitely a private home.

“This isn’t it,” Michael said.

“But this is where the map says it should be,” Nancy objected. “And the B&B sign pointed in this direction.”

“Where did you see that sign again? Maybe we didn’t go far enough.”

As we turned to go back to the sign, our headlights picked out another one, even smaller than the first: “Als Kloster B&B,” with an arrow. Michael had been right; we hadn’t gone far enough down the dark, unpaved road. Another left turn about a hundred meters on finally took us to Als Kloster. We were relieved to see a clearly marked, well-lit doorway for Room 3, with the code entry box right next to it.

As we hurried to get our bags out of the car without getting too wet, a woman came out of the building on the other side of the parking area. “Nancy?” she called.

“Yes!” Nancy called back.

“Welcome to Als Kloster! I’ve been expecting you. You’ll be in Room 3. I’ll go unlock the door for you.”

After all we’d gone through to retrieve the key code, we didn’t need it after all.

Room 3 at Als Kloster

Our spacious bathroom at Als Kloster

Room 3 is up one flight of stairs in a building that appears to have been newly renovated. Spacious and simply decorated, it has all the amenities we could need. But right now, all we really need is a warm, dry bed.

Leave A Comment