Eva and Barry

Anthony

We had set our alarm for 5:00 am, which came way too soon. Despite the low whomp-whomp of the ceiling fan and the occasional clatter of monkeys scampering across the roof, we had slept pretty well. The shower–tiled as nicely as the one at home–offered a warm if weak stream of water. We tried to remember to keep our lips sealed as water ran over our heads and down our faces, just as we try to remember to rinse our toothbrushes and even contact lenses with bottled water. Who knows what unseen dangers lurk in the stuff that pours out of the tap?

This morning we teamed up with Eva and Barry for the day’s first game drive, which began before dawn. Driver Anthony knew just where to take us to get a stunning view of the rising sun.

Sunrise over Samburu

Baboon resting in an acacia tree

Baboon troop in search of breakfast

Daylight brought a troop of olive baboons out of the trees near a spring and sent them up the dirt track we were following. The troop comprised dozens of individuals of all sizes: a few big males, more medium-size females, and lots of juveniles, including some tiny babies that either hung from their mothers’ abdomen or were perched on their backs. Although the baboons moved en masse, this was no military parade with orderly formations; it was more like a class of grade-school kids tuned loose for recess and heading for the playground.

Driving what at first seemed aimlessly around the reserve, Anthony took us past a variety of grazing animals: impalas, gerenuks, gazelles, oryxes, zebras, and giraffes. We saw a couple of diminutive dik-diks; they are among the smallest of the antelopes and therefore can be hard to spot in tall grass. Unlike most of their larger cousins, dik-diks do not live in herds, but in monogamous pairs. Anthony’s trained eyes also spied several interesting birds along our route, and each time he stopped to let us photograph them.

Grant’s gazelle

Vervet monkey

Günther’s dik-dik

Gerenuk

Spur-winged lapwing

Red-billed hornbill

The kori bustard is the heaviest flying bird native to Africa

Leopard

A phone call from another driver informed us that the elusive leopard was now lounging in a tree not far from where we had seen him yesterday, so we hurried back toward the creek. Today he was less reticent to let us take his photo.

Elephant mother and baby

On the way back to the lodge for breakfast, we discovered a herd of at least eighteen elephants munching on the shrubs. Baby elephants are so cute!

During this morning’s drive, Eva asked Anthony whether he had a family, and he ended up telling us how he had met his wife. Not long after becoming a guide, one of a new set of tires on his vehicle had blown out. (As you can imagine, good tires are essential equipment on safari.) Because they were still under warranty, Anthony called the manufacturer, explained his situation, and was given the name and number of a local dealer to contact for a replacement. When he visited the dealership to exchange the tire, he was disappointed to find that they did not have exactly what he needed in stock, but he was impressed with the customer service rep who handled his case. Not only was she competent and courteous, but pleasant and pretty, too. Completing the deal required several more phone calls and another visit. Each time, Anthony was more impressed with the service rep. Casually asking about her family, he determined that she was unmarried, so he asked her if she’d be interested in meeting him for coffee sometime.

“How about tomorrow?” she replied. Apparently, she had been equally impressed with Anthony. They married a year or so later and now have two children.

Passion fruit

The breakfast buffet was ready when we returned to the lodge. Today’s outstanding gustatory experience was eating fresh passion fruit, carefully scooping the gelatinous pulp out of the tough rind as one would a grapefruit. Passion fruit are about the same size and shape as limes; the seeds add a tart zing to the sweet pulp, so there’s no need to spit them out. We really wonder why this divine, flavorful fruit is not sold more commonly in the U.S.

After breakfast, the group left the game reserve to visit a village located about ten miles away. We rode with Mark and Lynn in a Land Cruiser from which the window glass had been removed. No doubt this had been a boon to photographers during the early morning game drive, but now it was a bane for us because Geoffrey (pronounced JOE-frey) was driving fairly fast, stirring up clouds of dust from which there was no escape. By the time we arrived at the village, copious tears had traced pinkish lines through the brown dust coating Nancy’s cheeks even though she had tried to keep her eyes shut. Road noise also made it difficult to hear Geoffrey’s briefing on Kenya’s ethnic groups and tribes, so we had to keep our ears open, if not our eyes.

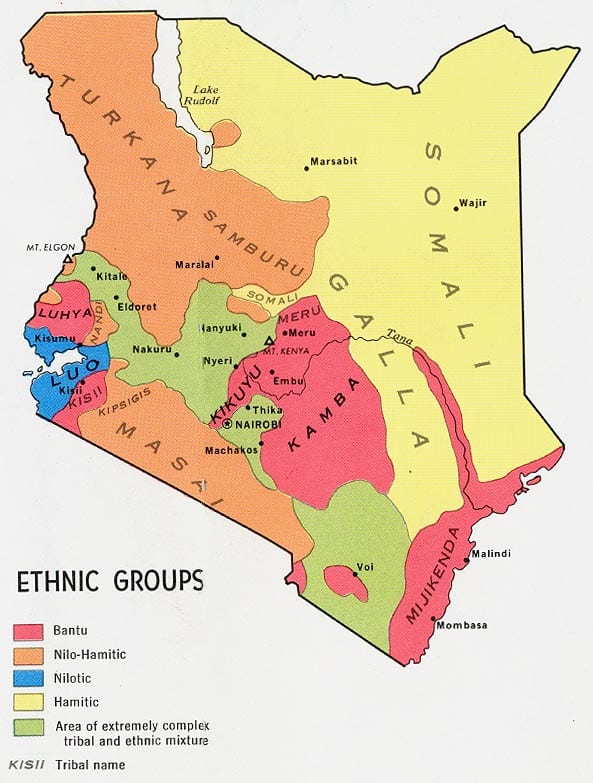

There are three major ethnic groups in Kenya: the Bantu dominate the central and eastern coastal regions while Nilotic peoples occupy the west and south; the small Cushitic minority can be found in the northeast. Of the forty-plus tribes these ethnicities comprise, the Bantu Kikuyu tribe is the most populous, representing about twenty percent of all Kenyans. All of Discovery XA’s driver-guides are Kikuyu, and it is that language we hear most often crackling over the CB radio during our drives. Swahili (or more correctly, Kiswahili, the prefix ki- meaning “language”) is a Bantu tongue that, along with English, is Kenya’s lingua franca, so our drivers use that when communicating with other native guides who are not from the Kikuyu tribe.

There are three major ethnic groups in Kenya: the Bantu dominate the central and eastern coastal regions while Nilotic peoples occupy the west and south; the small Cushitic minority can be found in the northeast. Of the forty-plus tribes these ethnicities comprise, the Bantu Kikuyu tribe is the most populous, representing about twenty percent of all Kenyans. All of Discovery XA’s driver-guides are Kikuyu, and it is that language we hear most often crackling over the CB radio during our drives. Swahili (or more correctly, Kiswahili, the prefix ki- meaning “language”) is a Bantu tongue that, along with English, is Kenya’s lingua franca, so our drivers use that when communicating with other native guides who are not from the Kikuyu tribe.

Kenyans speak their tribal languages at home, but must learn English early because all school classes are conducted in English, as are most commercial, business, and government transactions. Kenya’s other official language, Kiswahili, is used mostly for conversation. Our guides told us that even though Kenyan students are required to study literature as well as grammar in both English and Swahili, most kids expend more energy learning to read English than Kiswahili because they know our own native language will be more important for their future success. As a result, most store signs, newspapers, and other written materials here are in English, not Kiswahili.

The village we visited this morning is home to thirty members of the Samburu tribe, which comprises a very small part (0.5%) of the Nilotic ethnic group. The tribe is divided into nine clans, each with its own chief. The nine chiefs form a tribal council when coordinated action is necessary. If a clan becomes too big to administer effectively, several families may split off to form a new one. We learned that the clan to which this village belongs comprises twenty families–eight of which are headed by the wives of the clan’s polygamous chief.

Samburu warriors

A man named Jorai, one of the chief’s sons, welcomed us to his village and then introduced a group of adult men–“warriors”–who proceeded to perform a greeting song. That was followed by another song about lion hunting, during which the men randomly took turns stepping forward to demonstrate their strength by jumping as high as they could straight into the air. (Jim directed our attention to a young man in orange who had lost his lower right arm to a lion.)

Samburu women singing a welcome song

Next it was the women’s turn to greet us. They, too, sang a welcome song and then invited a few women from our group to join them as they performed a love song and showed how to make their elaborate bead necklaces bounce up and down on their chests provocatively to attract admiration–and suitors. (See the video below.)

By tradition, a young Samburu boy becomes a warrior when he reaches puberty, after enduring circumcision in a public ceremony and then leaving the village for an extended period. During his time away he is expected to fend for himself. Once he has proven that he can help protect and provide for the village, he may return. Several years later, when he is old enough to take a wife, his parents will negotiate for a woman from outside their own clan, offering eight to ten cows as a dowry. The man’s mother will then direct the construction of a home for the newlyweds within the confines of the groom’s village.

Samburu home

Samburu homes are framed with slim branches and then covered with cardboard and plastic tarps, held in place with bungee cords. Each one-room hut measures about 8’ x 10’, with separate corners designated for cooking and sleeping.

Children’s bed

Jan and Steve inside a Samburu home

Young children sleep in their parents’ hut; older children move into nearby sex-segregated dwellings at age eight to ten. Women are expected to build and maintain all of these structures, which need to be replaced every year. It seems clear, however, that everyday life among the Samburu goes on largely outdoors–not surprising for a society that only recently ceased being nomadic.

Livestock pen

Most of the daily work of the village is done by the women and children, who fetch water, prepare food, wash clothes, and tend the livestock. Each morning, teen boys release the cows and goats from separate enclosures formed from brambles and thorny acacia branches and drive them beyond the gate of the similarly enclosed village, where they will spend the day foraging–and trying to avoid predators. Village elders whose bodies have grown too worn for regular labor gather under a spreading acacia tree to discuss whatever old men discuss, while old women sit in scraps of shade provided by smaller shrubs and give orders to their grandchildren. Preteen girls carry babies on their hips or hold toddlers’ hands as they do their chores.

Village schoolroom

Village children have the opportunity to attend a state-run school located in a town several miles down the road, but we’re not sure how often they go or how many hours they spend in class. This morning we observed children gathered cross-legged under a tree for instruction by the village schoolteacher. Sticks and soft brown dirt serve as pencils and paper, chalk and chalkboard for students and teacher alike. The children sang us yet another welcome song, as well as an ABC song whose tune and cadences were very different from the “Twinkle, Twinkle” version familiar to American children. Also, the Z at the end was pronounced “zed.”

Teen girls outside their hut

It was not easy to distinguish between boys and girls because hardly anyone in the village has hair longer than half an inch. When we inquired about this style preference, a woman who spoke English well explained that kids who attend the school in town are required to have their heads shaved once a month, presumably for hygienic reasons, and most adults seem to follow suit. The children all wear a mishmash of western-style clothing, while adults of both sexes wear similar wrap skirts and drape-style tops–everything brightly colored. Most people wear sandals, and most adults adorn themselves with a variety of bead jewelry. Married women can be identified by the copper tubes in their earrings.

One ancient tradition that many people are hoping to eradicate among the Samburu and other African tribes is that of female circumcision. Although the practice is illegal in Kenya, many girls continue to be subjected to genital mutilation at puberty. We met some women who are traveling from village to village, trying to convince tribal elders that such mutilation is unhealthy and unacceptable in the modern world. We pray that their advice will be heeded.

Jorai explained that each village has a medicine man and a blacksmith, important positions that are passed from father to son. When he is not treating patients, the medicine man spends his days collecting healing herbs, and teaching his sons how to recognize and use them. The blacksmith supplies the village with tools and weapons. His usual charge is one goat for a machete, two goats for a spear. The medicine man also is paid in goats for his services.

Goats are an essential element of Samburu society

It seems that the Samburu could not exist without goats. Not only do they use them as currency for everyday transactions, but they depend on them for the meat, milk, and blood that make up most of their diet. We were surprised to learn that the Samburu don’t even attempt to grow grain or other produce, although since aid workers started encouraging them to feed their children a more varied diet, they sometimes barter for fruits and vegetables. Cattle also provide milk and blood, but not meat. While the Samburu don’t exactly regard them as sacred the way Hindus do, cows are never slaughtered because they represent a man’s wealth.

parliament

In the center of the village is an area demarcated by a circle of stones, about six meters in diameter. This is the “parliament,” where the men of the clan meet around a fire to discuss clan politics and resolve disputes. Infractions against tribal law are punishable by fines–which are levied in cows–or by curses invoked by the chief.

A small stone-strewn circle near the parliament marks the grave of a respected elder who died ten years ago at age 99. Samburu dead are buried with the head facing north toward Ololokwe, the holy mountain

Samburu warriors demonstrated how to start a fire using only a stick and some dried elephant dung. (Mark says he finally became proficient at doing this after weeks of practice, but he prefers using dryer lint as tinder)

Market

While some of the men ushered visitors into their homes for a brief look inside, the women set up a market displaying hundreds of bead bracelets and necklaces, along with hand-carved wooden animals and other trinkets. The villagers claimed that everything was their own handiwork, although we saw no evidence of carving or jewelry-making anywhere. We bought some gifts for our grandchildren, paying at least three times what the items were worth because it seemed unconscionable to drive a hard bargain with people living in such dire poverty. We were allowed to pay in dollars rather than in goats or cows.

Before returning to the lodge for lunch, we walked a hundred meters or so beyond the village to one of the four public wells that Jim and the Discovery XA Foundation have dug in the area. Local wells not only provide villagers with reliable sources of clean water; they also allow children to spend more hours in school when they no longer have to make a long trek to the Ewaso Ng’iro River several times a day. While a group of enthusiastic youngsters were showing us how easy it was to use the hand pump, a representative from another NGO happened to come by, eager to learn why Jim’s wells have been more successful than any constructed in the area by other groups.

A well constructed by the Discovery XA Foundation provides water for several villages

Jim was happy to explain. First, he told them, he includes local tribal councils in the planning and construction of each well, ensuring that no one person or clan tries to exercise exclusive rights over the water. Next, Discovery XA consults expert hydrologists to determine the best places to dig, and is committed to digging as deep as necessary to reach pure water rather than just the sludgy stuff that may eventually clog the system. (This one is more than 100m deep.) Finally, Jim’s foundation not only provides well-made pumping equipment, but also funds for the continuing maintenance that is critical for keeping the wells operational. The Gees hope to raise enough money to dig and equip at least a dozen more wells in Kenya; click here if you’d like to contribute to the effort.

Geoffrey graciously cleared off the shotgun seat in his Land Cruiser so that Nancy and her hard contact lenses could ride more protected by the windshield during the dusty drive back to the lodge. We may have failed to mention that Kenyans drive on the left side of the road, British style, so the shotgun seat is to the left of the driver. In Geoffrey’s vehicle, the seat had been piled with well-thumbed guides to the flora and fauna of eastern Africa, in addition to his camera and communication equipment. Each of the guides we have traveled with so far has displayed an impressive breadth and depth of knowledge, not to mention incredible skill behind the wheel. We’re grateful that they also keep the coolers in the back of each vehicle well stocked with bottled water.

Superb starling

Today we were forced to share our lunch with a horde of superb starlings who swooped down to grab morsels from our plates. These birds are every bit as obnoxious as their European/American cousins, but we’re more inclined to forgive their rude behavior because they are indeed superbly beautiful: iridescent blue -green on top, fiery red-orange below, accented with bands of white, and rows of glittering spots on the wings that look like so many sequins.

Brown-throated weaver

White-headed buffalo weaver

Golden palm weaver

Common bulbul

Another variety has a golden yellow breast and a long, graceful tail. Most of the birds here are brilliantly colored, as if they could not care less about hiding from predators. Michael has been trying to photograph as many different species as he can (we’ll worry about identifying them later) but few are willing to sit still enough for a good portrait.

The dining room attendant is employed to chase birds away, but he spends more time playing the same five-note tune on his flute

Nancy and Michael cool off at the pool. Several elephants are hiding in the shrubs just behind us

After our hot, dusty morning, the swimming pool looked irresistible this afternoon. A herd of elephants had the same idea and made similar use of the river just across the ravine. Our water was clearer than theirs, but probably not as warm–definitely bracing at first, but ultimately refreshing.

The balcony outside our room would have been the perfect place to hang wet swimsuits had we not been warned about marauding monkeys, so we strung up a clothesline behind the glass doors before gearing up for the 4 pm game drive.

Tawny eagle

Tawny eagle

Somali ostrich

Maasai ostrich

Eva and Barry beckoned us to join them in Anthony’s vehicle once again. For the first hour or so, we trained our cameras mostly on birds: tawny eagles and ostriches. Anthony taught us how to distinguish between the two ostrich subspecies that inhabit this reserve: the Maasai has a pink neck and legs, while the Somali’s neck and legs are gray.

Anthony also shared some intriguing information about the oryx, a large member of the antelope family that is well adapted to this semi-arid climate. It has perfected the physiological trick of regulating its own body temperature, raising it as high as 116°F so that it does not have to drink as often. A unique circulation system within its head diverts blood through capillaries in its nose to reduce the temperature before it enters the brain. Cool, huh?

Anthony also told us about the strange case of Kamunyak, a lioness in the Samburu Reserve who became famous after “adopting” six baby oryxes in succession during 2002. Kamunyak (Kisamburu for “blessed one”) would separate the newborns from their terrified parents and then proceed to protect and cuddle with them for several days. Sometimes she would allow the mother to come back and nurse her calf for a while, but the oryx mothers were understandably skittish and the lioness inevitably drove them away. The first adoptee was snatched by another lion when Kamunyak momentarily dropped her guard; the next few were rescued by park rangers when it became obvious that the baby oryxes were on the verge of starvation. With the fifth, rangers decided to just observe while nature took its course. After the little oryx starved to death, Kamunyak ate it–much to the horror of the tourists who had gathered to watch–but the lion herself must have been near starvation because taking care of her charge had prevented her from hunting. The parents of the sixth adoptee managed to outwit the lioness and reclaim control of their little one the day after they were separated. Eventually Kamunyak became the subject of a movie, but no one knows what finally happened to her after she was last seen in 2004.

Can you spot the cheetah mother and cubs?

Cat watchers

Unlike most cats, cheetahs are daytime hunters. Black streaks under their eyes help reduce glare

Later this afternoon we were able to witness more normal mother-child relations, when Anthony received word that the cheetah family we had seen napping yesterday were now on the move. Our converging vehicles probably prevented the mother from focusing on chasing down a meal, but anyway the four cubs parading behind her seemed more interested in fun and frolic than food. We reluctantly left them only because we had to return to the lodge by sundown.

All of us reported to the dinner buffet when it opened at 7:30 pm, but like the cheetahs, we were more interested in fun and conversation than food. No matter how many hours there are between meals, the intervals never seem long enough for us to develop an appetite–yet we continue filling our plates because there are always new dishes demanding that we take a taste. Tonight, however, Nancy decided that she could safely skip the roasted meats because even though they look good, every piece she’s sampled here previously has been tough.

Before

During

After

This afternoon’s game drive replaced the sweat and road dust that had washed off in the pool, so we felt pretty grimy getting into bed tonight. We leave Samburu tomorrow, so at least we won’t have to sleep in the same sullied sheets–but now we’ve begun to worry about what all this dust must be doing to the insides of our cameras.

Leave A Comment