Today is the 75th anniversary of D-Day. Although the Allied invasion occurred on the shores of Normandy, it had a profound effect on central Europe as well. All of us should be grateful that neither the Nazis nor the Allied bombs that torched Dresden less than a year later ever targeted Prague for similar destruction. That Prague survived World War II nearly intact is one of the reasons visitors are so charmed by this beautiful city.

Eva the Voluble met us at the hotel just after breakfast, ready to lead a walking tour through Prague’s historic center. As we waited in the lobby for our group to gather, Eva showed us (and offered for sale) a selection of her own watercolors. Although Michael and Nancy have been collecting small artworks as mementos from each of our trips, we decided to pass on any of our guide’s colorful, splashy creations.

Republiki Square

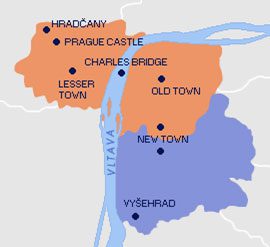

Eva directed us to turn left as we exited the hotel, which is located only a block from Republiki Square, where a farmer’s market takes the place of vehicle traffic in the wide boulevard that divides Old Town from New Town. Having been established in the 1300s, New Town isn’t exactly new, but since it was built up more than a century after Old Town was recognized as an autonomous settlement, the “new” name stuck. Eva explained (sort of—we had to look up clarifying details later) that Prague really began to prosper in the fourteenth century under Charles IV, a Bohemian king who later became Holy Roman Emperor. In 1348 he established Charles University in Old Town, the first university in central Europe; he also promoted economic development in nearby New Town to stimulate a growing community of merchants and tradesmen. Eventually these towns merged with Menší Město (Lesser Town), the community beneath the castle on the other side of the Vltava, to become the city of Prague.

Old, New and Lesser Towns

The name–Praha in Czech–is derived from the word for threshold, and according to legend can be traced to a prophecy by the visionary ninth-century Bohemian princess who became the matriarch of the Czechs’ ruling dynasty. Princess Libuše foretold the rise of a great castle and city “whose glory will touch the stars” on a rocky promontory overlooking the Vltava. “Just as princes and dukes stoop in front of a threshold,” she went on, “they will bow to the castle and to the city around it. It will be honoured, favoured with great repute, and praise will be bestowed upon it by the entire world.” The castle she ordered to be built on the site she had seen in vision became known as Praha Hrad (Threshold Castle).

Municipal House with a mosaic of Princess Libuše

Our walking tour took us past the main entrance of the Municipal House, where a golden mosaic depicts Princess Libuše and the city she envisioned. This Art Nouveau-style venue for concerts, operas, ballets, and fashion shows is located across the street from our hotel, so we were already well acquainted with the sculpted figures along its north side, which we can see from our room.

Prašná Brána (Powder Tower)

Proceeding east along Celetná, one of Prague’s oldest streets, we passed the Prašná Brána (Powder Tower), one of the city’s original gates, and then the Český Kubismus (Czech Cubism Museum). In the early 1900s, many Czech artists and architects visited Paris and were inspired by the work of Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque; soon they developed their own take on Cubism. The museum is housed in a building designed by Czech architect Josef Gočár in 1912, called the House of the Black Madonna because it stands on the site of a baroque-era mercantile institution, which was decorated with a figure of the Virgin Mary carved from black stone.

Český Kubismus (Czech Cubism Museum)

The baroque-era Black Madonna adds a wildly anachronistic touch to Prague’s Cubism Museum

Continuing along Celetná, we passed Charles University and then came to the Town Hall, where we had to stop and watch the astronomical clock go through its twenty-eight second routine once again for the benefit of group members who had not yet experienced it.

Unicorn House

Stone Table

Kinsky Palace

Eva then led us into Old Town Square, where she pointed out a number of places with historic if not architectural significance: the Unicorn House, where composer Bedřich Smetana once operated a music school; the Kinsky Palace, where Franz Kafka attended school as a child; and the Stone Table, home of a literary salon that attracted some of the early-twentieth-century’s most noted writers and thinkers, including Kafka, Franz Werfel, and Albert Einstein. Eva also told us that “Kafka’s family kept a shop in the square, actually,” but she wasn’t sure exactly where it had been located.

Today, Old Town Square was being turned into a temporary outdoor concert venue in preparation for the Prague Street Music Festival, set to begin after we leave tomorrow [insert frowny face here], so we had to carefully skirt the construction zone as we crossed the square to meet the tour bus waiting near St. Nicholas Church on the other side. The bus took us across the Vltava River into Menší Město (Lesser Town), which had been the home of Prague’s wealthy citizens in centuries past. Most of the luxurious baroque residences in Lesser Town are now international embassies.

View of Lesser Town and Prague Castle

St. Nicholas Church in Lesser Town

On the central square is another large church dedicated to St. Nicholas, built by the Jesuits during the first half of the eighteenth century and considered the finest example of the baroque style in Prague. Unlike the city’s other St. Nicholas Church (curiously, both were designed by the same architect), this one is still operated by Roman Catholics—although, during the Soviet era, its tower was used by Communist spies to keep tabs on the nearby American, West German, and Yugoslav embassies.

Strahov Monastery

Eva gave each of us a package of delicious chocolate-hazelnut-filled wafers for a snack

The bus climbed the bluff that Princess Libuše had seen in her vision toward Prague Castle, but our first stop was not at the castle but at the Strahov Monastery. The long white building with twin towers is one of the most prominent features of Prague’s west bank, significant mostly for its age (founded in the twelfth century) as well as its library. The library building has survived since 1679, with a collection of over 200,000 books that includes several thousand old manuscripts. The onsite brewery also draws a lot of visitors.

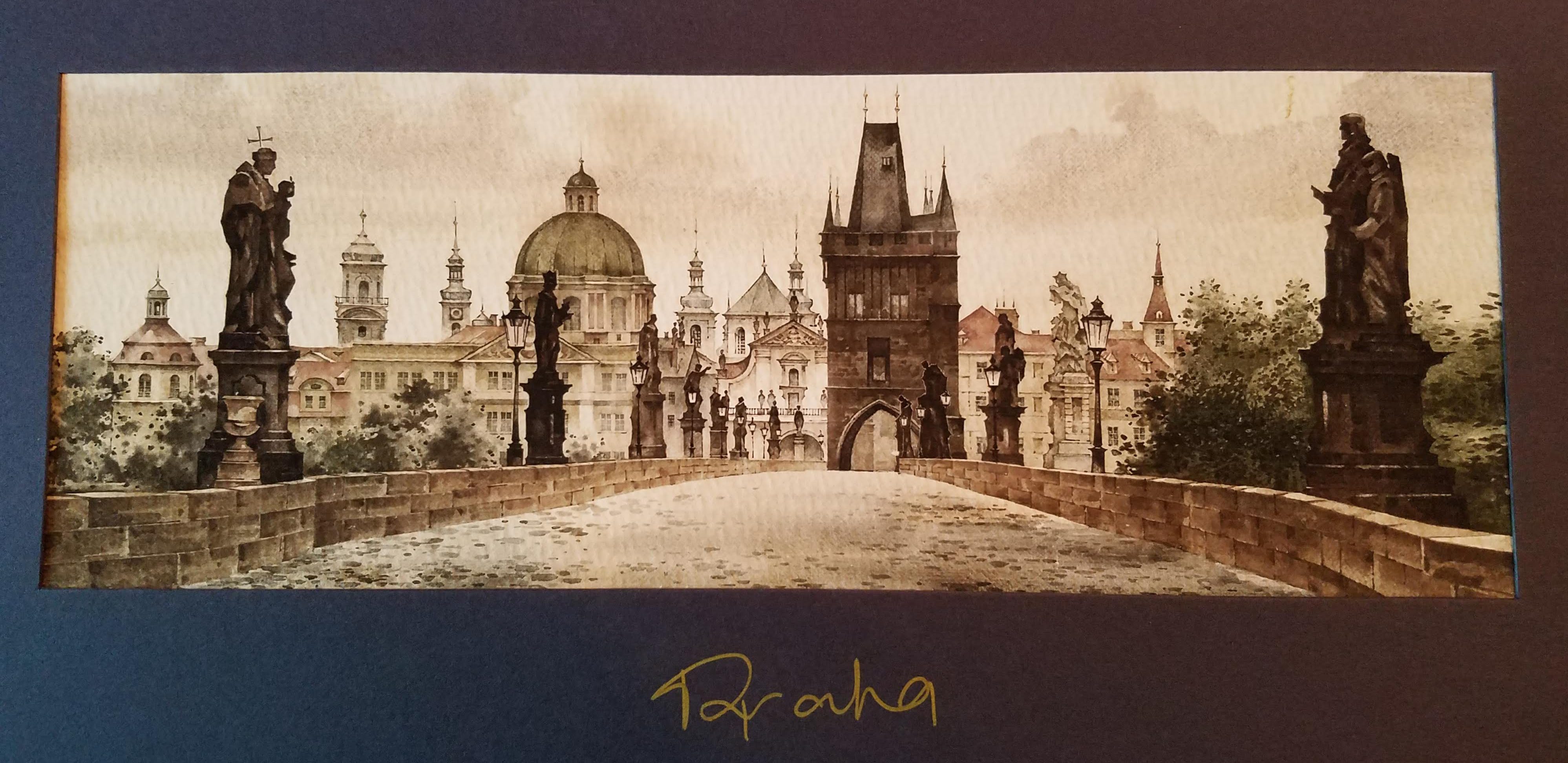

Our watercolorist

Our group visited neither the library (no reservation) nor the brewery (no interest), but we enjoyed browsing through the displays of several artists who had set up booths behind the monastery. We especially liked the work of one watercolorist whose style and subdued palette were more to our taste than Eva’s, so we purchased a small print of his view of Prague landmarks as seen from the Charles Bridge.

Our water color

We might have walked from the monastery to the castle, but Eva recommended that we get back on the bus and drive around to the castle’s garden entrance, where the line to get in was likely to be shorter. On the way, we happened to pass the same light-gray stone building that had caught Nancy’s eye on our way into Prague from the airport on Tuesday because she recognized a simple but distinctive sign. She couldn’t pronounce the words written on it (Církev Ježíše Krista Svatých Posledních Dnů), but the place was unmistakably The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. As we were about to pass it this morning, Eva drew our attention to it before Nancy could.

“Notice that light-gray building on the corner,” she said. “It’s the Mormon Church. There are a lot of Mormons in Prague, actually. I’ve talked with their missionaries several times. Most of them are Americans, but they speak very good Czech, actually. I don’t know how they manage to learn it so well.”

Everyone on the bus began to chuckle, but Nan was the one who called out, “We can tell you how they learn it: they spend eight weeks in an intensive language program at the Missionary Training Center in Provo, Utah, before they come. Did you know that all of us are Mormons?”

Eva had had no idea, actually.

The “singing fountain”

The line at the entrance to Prague Castle’s Royal Gardens was indeed not very long, so after passing through the security check we were soon within the compound, enjoying the formal landscaping and ducking our heads beneath the “singing fountain” so we could hear the music created by jets of water hitting the bronze bowl.

Belvedere, Queen Anne’s Summer Palace

The fountain stands in front of Belvedere, a lovely Italian Renaissance-style palace constructed in the sixteenth century for the wife of Ferdinand I. Sadly, she died before it was completed, but it is still known as Queen Anne’s Summer Palace. One of Ferdinand’s successors, Rudolph II, housed his art collection at Belvedere, and used the upper floor as an observatory where famous astronomers such as Tycho Brahe and Johannes Kepler often visited. It is now a museum, this month featuring a special exhibit on the fall of the Iron Curtain.

Ball Games Hall

Another large Renaissance-era structure on the south side of the Royal Gardens is the Ball Games Hall, sometimes used in the past for stabling horses as well as for sports, and currently serving as a concert venue and event center.

St. Vitus Cathedral in the Prague Castle compound

Castle courtyard

The Guinness Book of Records lists Prague Castle as the world’s largest ancient castle compound, so we had no hope of seeing more than a fraction of it during our one-hour visit this morning. The first walled structure on the site was a church erected in 870 A.D. Since then, a long succession of monarchs (and more recently, presidents) have added, repaired, remodeled, and restored buildings within the complex.

St. Vitus Cathedral

St. Vitus flying buttresses

The castle’s most imposing structure, St. Vitus Cathedral, was begun in 1344 by Charles IV, who wanted all citizens of Prague to have a place where they could gather. However, it would be a long time before the cathedral was finished. Fire ravaged the whole castle compound in 1541, so builders had to start over; St. Vitus was not completed until 1929.

The Last Judgment is depicted in a mosaic over the south portal of St. Vitus Cathedral

Castle guard

St. George the Dragon Slayer outside St. Vitus Cathedral

The cathedral’s bell struck twelve times while we were wandering around the plaza outside, taking photos. Soon we were back on the bus, heading for the Charles Bridge. This iconic landmark, named for Charles IV, who reportedly laid the cornerstone of its first support pillar, has tied Prague together since the fourteenth century. Until 1841, the bridge provided the only way across the Vltava River, so for centuries it made Prague a vital hub for trade routes linking eastern and western Europe.

Charles Bridge

Charles Bridge is now open only to pedestrians

A string trio was performing an electrified version of “The Moldau”

A jazz band was playing American standards

Closed to vehicles since 1978, the Charles Bridge now serves as a kind of outdoor art festival, lined with statuary, artists’ stalls, and street musicians all along its length. Locals are not entirely happy with the structural restoration project that was completed in 2010 because it was not conducted with the highest standards of historic preservation in mind; nevertheless, they are justly proud of the bridge and its important role in the city’s past. Eva had told us earlier that the bridge is “hoovered” every night (which made us wonder exactly where she had learned her English); that bit of information did not surprise us because we’d already noticed that this city is very clean.

Five stars circle the head of St. John of Nepomuk

Most prominent among the many statues decorating the Charles Bridge is a figure of St. John of Nepomuk. John was a Bohemian cleric who had the misfortune to clash with King Wenceslaus (son of Charles IV), who had him thrown from the bridge and into the river, where he drowned. Stories about the reason for their conflict vary. Some say that John lost the king’s favor when he confirmed the pope’s pick to head an important abbey rather than the candidate Wenceslaus backed; more romantic accounts hold that the king became enraged when John, confessor to Queen Johanna, refused to divulge the queen’s secrets to him. Either way, everyone agrees that Wenceslaus (not the “good king” of the song) ordered John of Nepomuk to be drowned in the Vltava on 20 March, 1393. Witnesses said that at the moment John entered the water, five new stars appeared in the sky, and it wasn’t long before the martyred priest was canonized. Since then, Czech Catholics have considered St. John of Nepomuk a special protector against floods and drowning—as well as calumnies.

Hotel InterContinental Prague

We boarded the bus again on the other side of the bridge and rode back toward our hotel through the northern part of Old Town. Eva told us that because all property near the river is public rather than privately owned, most of the buildings in this area are either government ministries or universities. Exceptions include the Convent of St. Agnes, now a museum, and the InterContinental Hotel, a Brutalist-style relic of the Soviet era whose greatest claim to fame—at least, in Eva’s mind—is that Michael Jackson stayed there during a 1996 tour.

Hotel Kings Court Brasserie and Cafe

It was about 1:15 p.m. when we returned to the hotel and we were hungry, so instead of climbing four flights of stairs just to drop off our daypacks, we decided to head directly to a brasserie down the street where Ed and Lisa had gotten a good pizza last night. It might have been pleasant to sit outside under the awnings, but most of the patrons seated there were puffing on cigarettes (in European restaurants, all outdoor seating is in the “smoking section”) so we went inside where the air was cooler and more pleasant. We shared a pizza topped with olive oil, thinly sliced potatoes, and parmesan cheese, and a caprese “salad” composed of a few arugula leaves and a couple of small tomatoes surrounding a large lump of fresh mozzarella, all drenched in oil—not bad, but not exactly the kind of “light lunch” we had pictured when we ordered. Only a few minutes after our food arrived, we spied Pam and Eric peering through the windows, so we motioned for them to come in and join us. We sat and talked while they ate, probably for another hour, taking advantage of our unstructured afternoon.

Krtek

Michael—who rarely sleeps well at night—was ready for a nap, so he went back to the hotel while Nancy walked on toward Old Town Square to shop for gifts for our grandchildren. Artisans in the Czech Republic produce beautiful wooden toys, so it was hard to choose. It was not hard, however, to pass over any figures of Krtek, a cartoon mole that seems to be the Czech equivalent of Mickey Mouse. We have seen at least one plush-costumed, adult-sized Krtek dancing in Old Town Square every time we’ve passed through it, but at first we weren’t sure what it was because, to us, the character looks more like a cross between a penguin and a panda than a mole. Eva told us that Krtek is very popular in Europe, and even has gone into space with an American astronaut whose wife is Czech.

The rain that had been forecast for this afternoon finally arrived about 4:00, just as Nancy was returning from her shopping excursion. She found Michael awake and working on blog posts, but she reminded him that we needed to start repacking. We have to be ready to leave the hotel at 6:00 a.m. tomorrow (ugh), and we wouldn’t have time to pack later this evening because we had planned what was likely to be a late night on the town.

At 5:00, we met Lisa and Ed in the hotel lobby. Our plan was to walk to Nostress Cafe, the restaurant Michael had chosen for tonight’s dinner, a little less than a kilometre away, but it was now raining pretty hard. It didn’t make sense to call a cab because the area between the hotel and the restaurant is closed to vehicle traffic, so we decided to just brave it through the storm. After all, the four of us were wearing our Columbia rain gear. (There have been many jokes among this group about how much of our collective wardrobe has Columbia labels. Maybe we should pose for an ad.)

Nostress Cafe Restaurant

We thought perhaps Nostress meant something different in Czech than it does in English, but it turns out that the restaurant’s proprietor really did want to describe the cafe as a place to relax and leave your worries behind. We arrived, dripping, about 5:30 and were lucky to secure the last table available, which was in the bar area next to a set of wide-open French doors. We tried to get the maitre d’ to let us take an empty table in the main dining room, but he declined, saying that it was reserved for a party coming at 7:00. We explained that we needed to leave by 7:00 because we had tickets for a 7:30 concert, but he wouldn’t cave “because we already have the table set for a party of six.”

No matter. The rain splashing on the sidewalk just outside the French doors soon abated, and the cool breeze that followed felt refreshing. Picking up the conversation where we had left off at lunch yesterday, we enjoyed more time with Ed and Lisa and another memorable meal. Both Nancy and Michael started with a bowl of carrot-cumin soup. For the main course, Nancy chose sea bass ceviche with passion fruit and sliced avocados (underripe, but not unpleasant), plus a side of sauteed spinach; Michael had beef sirloin with tomato-spinach-tarragon salsa, and a side of steamed vegetables.

Mango-passion fruit pavlova

As we were about to order dessert, Michael remembered that the main reason he had wanted to try Nostress was that it has an in-house bakery, so he, Ed, and Lisa went to the next room to look over the selection of pastries in the display case. Nancy didn’t go with them because she already knew exactly what she wanted, having been enticed by the mango-passion fruit pavlova described on the menu. (It was divine!) Michael was satisfied with the mango-topped cheesecake he chose from the pastry case.

Dvořák Hall

Our view from the organ loft

As promised, we were walking out the door by 7 p.m. and heading for Dvořák Hall, a short walk away. By the time we learned that the Czech Philharmonic would be presenting a concert tonight featuring violinist Joshua Bell, the only available seats were in the organ loft behind the orchestra, but having sat in similar seats at other concerts, we did not hesitate to take them. (Other members of our tour group had been invited to reserve their own tickets, but only Lisa and Ed decided to join us.) Bell performed the violin concerto by Camille Saint-Saens with characteristic verve—in marked contrast to the staid orchestra members playing behind him, and even to conductor Christoph Eschenbach. Our seats allowed us to see Eschenbach not from the back, but as the players saw him. His conducting style seemed hard to follow—not many clear downbeats—but apparently that didn’t faze the orchestra, which sounded crisp and confident. As an encore, Bell played a “miniature” by Antonin Dvořák, in company with the concertmaster (female) and principal second violinist (male). Again, Bell was a lot more demonstrative than the other players, but the audience received the performance with obvious enthusiasm.

Anton Bruckner’s Symphony no. 3 in D minor, dedicated to Richard Wagner and full of dramatic musical imagery, comprised the second half of the program. During intermission, Michael wondered whether the orchestra and its no-nonsense conductor would be able to deliver the kind of emotive sensibility the music demanded, especially with Bell no longer on stage with them. To our relief and delight, the drama and emotion of Bruckner’s music were clearly audible even though the musicians maintained their outward reserve.

Eschenbach applauding the orchestra after the Bruckner

The third symphony is long–over an hour—and our backless bench seats were not very comfy, but our position on the first row behind the orchestra had unique advantages. Not only could we see exactly what the conductor was doing, but we could clearly read the music of the string bass players standing just under the brass rail in front of us; indeed, we could have turned pages for them. It was fun to follow along with the score, and helpful to be able to gauge where we were in each movement. We almost felt like part of the performance itself.

Our impressions of the Czech people, based on our admittedly limited experience over the last few days: they may lack flamboyance, but neither are they cold. Their outward reserve masks deep feelings, and they live life with intensity and grace.

After the concert, our stroll back to the hotel took us again through Old Town Square, where all paths in this part of Prague seem to lead. Although it was late, a few shops were still open, which was good because Lisa was hoping to find some Koh-I-Noor watercolor pencils, which are manufactured here in the Czech Republic. Alas, her quest was unsuccessful because none of the shops we entered carried the specific kind she wanted—but we were successful at getting into bed by 11:00.

Great post, Mike and Nancy–I love all things medieval and will definitely add Prague to my bucket list (which may be fast becoming the “Resurrection Tour”). I wish you had been able to go to the old Jewish Quarter on your tour. Who are these Latter-day Saints you are travelling with? Are they people you know or a particular tour company? Great photos and history!

Our traveling companions were current and former members of our Montgomery Ward here in Cincinnati. We knew all of them. We chose the tour we wanted to do, then invited the traveling companions, and then asked some friends who have their own touring company if they would make the arrangements and come with us so they could add it to their options. Going with friends is a great way to travel.