Banana French Toast

Remembering the delicious-looking French toast Michael had ordered from the à la carte menu for breakfast yesterday, Nancy decided that this was the morning she would do the same rather than going through the buffet line. What kind of French toast will they be serving today? she wondered as she showered and dressed. Blueberry cheesecake? Caramel apple? To her deep disappointment, however, today’s à la carte menu announced that the French toast du jour was made with banana bread. While Nancy doesn’t mind eating a banana every now and then if there isn’t anything better to choose from, and while she will eat banana bread occasionally if that’s what’s being served, she doesn’t want bananas in her smoothies, she doesn’t want bananas on her peanut butter sandwiches, she doesn’t want bananas in her hot fudge sundaes, and she definitely didn’t want banana bread French toast this morning. Oh well. At least there was the buffet to fall back on, and the hope for a different kind of French toast tomorrow.

The view from the Star Breeze’s berth on the Neva River features the Winter Palace and the Admiralty complex

The temperature on deck was a little nippy, so we had to go back to our cabin for jackets before sitting down to eat with Ed and Lisa. NJ joined us (without Mary-Anne, who had decided to forego breakfast) and soon Nancy’s despondency over banana-contaminated French toast was overcome as NJ began amusing us with stories about his in-laws, Russ and Rita—may they rest in peace. Actually, Russ and Rita probably are resting much more peacefully now than they could thirty-some years ago when NJ, an Italian Mormon, informed them that he was going to marry their only daughter, an Irish Catholic, “whether they liked it or not.” According to NJ, years went by before Russ and Rita finally stopped regarding him as the Devil Incarnate and began to appreciate what a truly wonderful person (and very funny guy) he really is.

By 9:00 a.m. we had made it past the same grim security agents who had inspected us yesterday (we should have invited them to join us for breakfast; perhaps NJ could have persuaded them to crack a small smile) and boarded the bus for today’s tour.

Father Frost

Because Marina had allowed us no opportunity to shop for souvenirs yesterday, some of us had requested a shopping stop some time today. Marina complied first thing this morning by directing the bus to drop us off outside a large store with two floors full of overpriced matryoshka dolls, Ded Moroz (Father Frost) figures, jeweled reproduction Fabergé eggs, fur hats, paintings, and lesser tchotchkes. It was the only place in the vicinity that was open, and obviously the retailer with whom Marina had a business agreement.

Nancy tries on a Snegurochka headdress

Realizing that this was likely to be our only chance to buy mementos of our visit to Saint Petersburg, we perused the racks of tree ornaments and found some hand-carved, egg-shaped Father Frosts that wouldn’t break our budget and bought several to give to our kids. Father Frost is eastern Europe’s equivalent of Santa Claus, bringing gifts to children on New Year’s Eve. Although his origins are pre-Christian, the Soviets tried to ban the mythological figure as too religious and “bourgeois,” but the kids rebelled and kept him alive in Russian New Year traditions. Unlike Santa Claus, Ded Moroz has no elvish assistants; instead, he is accompanied on his rounds by his daughter, Snegurochka, the beautiful Snow Maiden.

When everyone had finished purchasing their souvenirs and returned to the bus, we continued toward our primary destination for the morning: Peterhof, Peter the Great’s favorite residence, which is situated on the Gulf of Finland about 20 miles west of the city—although it is now considered within the greater metro area. Driving along the Saint Petersburg-Peterhof Highway, Marina explained that we were traveling part of “The Green Belt of Glory,” a chain of parks marking what had been the city’s line of defense during the siege of Leningrad in World War II and including many small memorials honoring the soldiers who held that line.

A memorial canal in Orlovsky Park on the Green Belt of Glory

A massive Soviet-era apartment block

The highway also honors (perhaps inadvertently) the memory of less noble aspects of the Soviet era: we passed numerous drab apartment blocks built in the 1950s and 60s, which Marina says have been updated and upgraded since being transferred from state ownership to private developers. Such projects must have required extensive remodeling; Marina told us that many Communist-era apartments did not even have kitchens because laborers and students generally ate in communal dining facilities at work or school.

More modern apartment buildings

The Baltic Pearl commercial/residential complex

During the Stalinist era, this building in the Kirovsky District was an academy for Soviet youth

Beyond the bland behemoths of the past are a number of more stylish residential and commercial buildings. Marina pointed out a large multi-use complex that opened six or seven years ago.

“It’s called the ‘Baltic Pearl,’” she said, “but most people here refer to it as ‘Chinatown’ because it was built by the Chinese.”

Green Belt Tram

A dacha on the Saint Petersburg-Peterhof Highway

As we drew closer to Peterhof, Marina told us to watch for dachas, vacation houses of the privileged class. Some of these were built in the nineteenth century for the aristocrats who accompanied the czar and his family to their summer resort, and later were taken over by members of the Politburo; others date from the mid-twentieth century. There the wealthy and well-connected could (can?) escape the noise and squalor of the city and relax behind privacy fences, enjoying luxuries forbidden to the proletariat: imported foods and wines, electronic gadgets, and Hollywood movies.

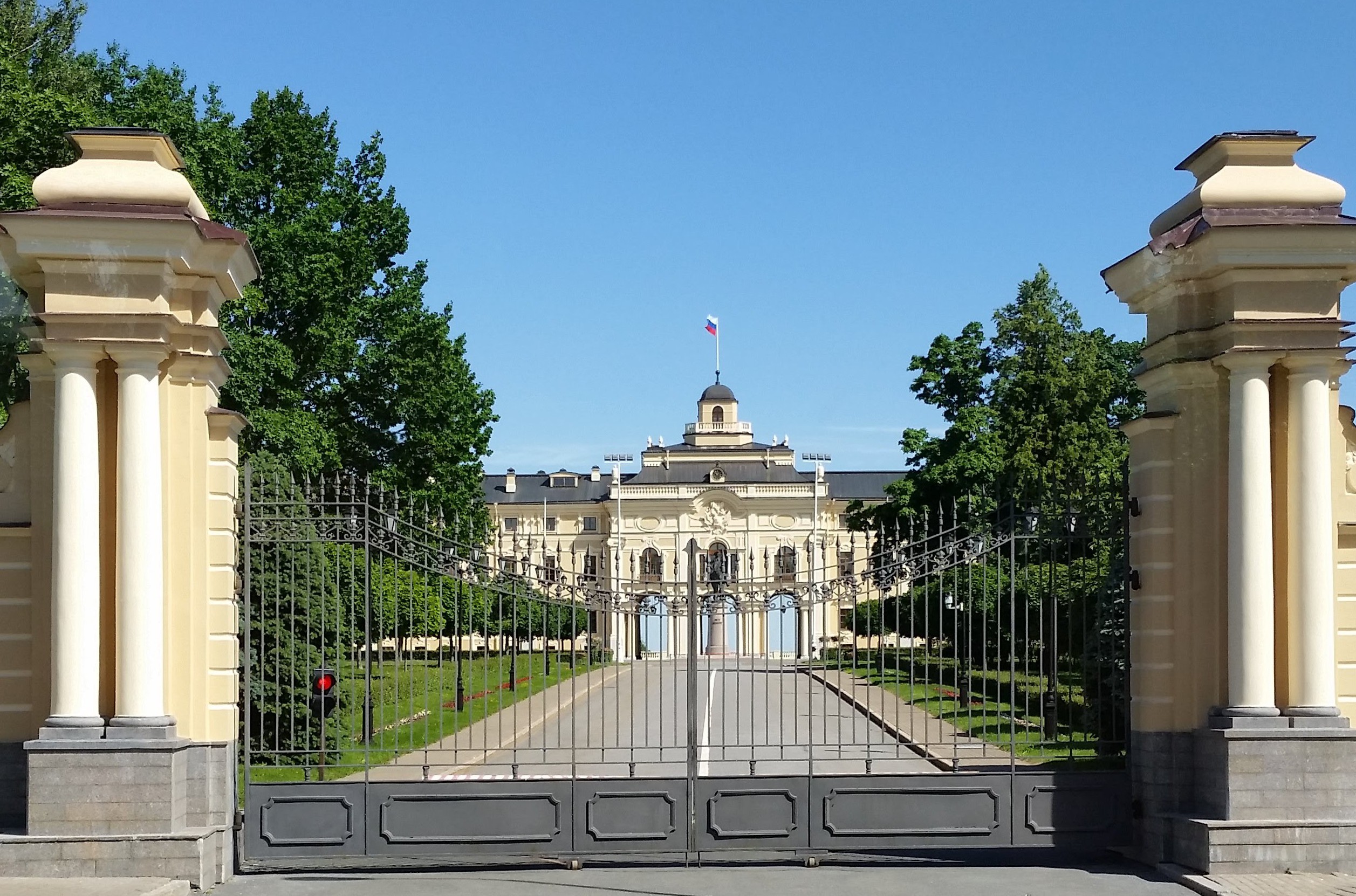

Konstantin Palace

The largest of the aristocratic retreats we passed on the way to Peterhof is the Konstantin Palace. It was built on the plot Peter the Great originally chose for his summer palace, but abandoned when his French landscape architect—who had worked on the gardens of Versailles—determined that the site was unsuitable for all the fountains Peter had commissioned. Eventually, the mansion Peter had begun there was completed on a less grandiose scale and turned over to Grand Duke Konstantin, the second son of Czar Paul I. Today the palace serves as a presidential residence and state conference center, with eighteen luxurious seaside “cottages” for visiting dignitaries.

Waiting to get into Peterhof

While we waited to get in, we had fun thinking of other questionable activities that this sign does not specifically prohibit

When we finally arrived at Peterhof, we found it mobbed by other visitors. Marina reminded us that today is Russia Day, a national holiday commemorating the country’s return to sovereignty in 1992. (We have visited four nations thus far on our trip, and have managed to hit national holidays in three of them!) Even though many Russians don’t consider the dissolution of the Soviet Union an appropriate occasion for celebration, they don’t mind getting the day off work, and today it appeared that everyone in Saint Petersburg had decided to spend their holiday at Peterhof. We mingled with the crowd outside the gate while our guide waited in line to buy tickets for our group, and then, when we determined that Marina had made it to the ticket window, we all got in the security-check line to save additional wait time.

The Samson Fountain at the head of the Sea Channel that reaches toward the Gulf of Finland

The Peterhof complex is frequently compared to Versailles, but despite the fact that the Russians employed some of Versailles’ designers for their own project, the two estates are very different. The most obvious difference is that Peterhof was completely destroyed during the Nazi occupation from 1941-1944, so what we see today are reconstructed buildings and gardens rather than conserved originals. Restoration work has been ongoing since 1950, and surged in the years prior to the three-hundredth anniversary of the founding of Saint Petersburg in 2003. Fifteen-hundred of the four thousand artworks displayed at Peterhof when the Soviet Union became involved in World War II were evacuated before the arrival of the Nazis; of those, a thousand are still missing. Not many of Peter’s original collection had survived into the twentieth century, anyway, because no provisions had been made to protect them against cold, heat, and moisture when the summer residence was unoccupied.

Peterhof also differs from Versailles in that the Grand Palace sits atop a bluff overlooking the entire estate and beyond to the Gulf of Finland. It was the slope of the terrain and the presence of natural springs that landscape architect Jean-Baptiste Le Blond exploited for Peterhof’s 150 fountains and four cascades.

Eve Fountain

“Favourite” Fountain: ducks pursued by a dog rotate around the pool

Umbrella Fountain: sitting on the bench activates the water streaming down around the perimeter

The fir trees in the foreground are actually trick fountains that unexpectedly shoot water from their branches

The Samson Fountain and the Grand Cascade below the Grand Palace of Peterhof

The grounds are laid out in the French style with the largest water features near the Grand Palace, but again unlike Versailles, there are many smaller fountains throughout the Lower Gardens. Le Blond’s ingenious gravity-fed water system employs 22 kilometers of aqueducts; it requires no pumps, but can supply enough water to keep the fountains and cascades operating up to ten hours a day. The most spectacular water feature is the Grand Cascade, with the Samson Fountain at the bottom. The fountain depicts the biblical hero wrenching a lion’s jaws open, and commemorates Peter’s victory over Sweden (represented by the lion) on St. Sampson’s Day. The Grand Cascade and the 20-meter vertical jet that shoots from the lion’s mouth are impressive, but the water features we liked best were the “trick fountains” that Peter had built in several places in the Lower Gardens. To the casual observer these look like plants or benign sculptures, but when unsuspecting visitors touch them or step on certain stones in the walkway, they trigger sudden sprays that can soak everyone around.

Monplaisir Palace

Down the major promenade from the Grand Palace are two smaller, more intimate palaces built right on the edge of the gulf. Marli Palace initially served as a guest residence for visitors to Peterhof, but later became a sort of museum for Peter the Great’s personal effects. The other small palace, called Monplaisir (My Pleasure), acted as Peter’s “man cave” until his death in 1725. His wife, Catherine I, then ordered the construction of another wing for their daughter Elizabeth. The wife of Elizabeth’s nephew, Peter II, was living in that new wing when she learned that the coup she had launched against her husband had been successful, so it was from Monplaisir that Catherine II consolidated power to become Empress of Russia.

A mallet trio entertained visitors waiting to use the toilets. The line for the women’s side was so long that several females from our group decided to use the men’s side, scandalizing less liberated male tourists

The Peter and Paul Chapel at Peterhof

Another later addition to the complex is the Peter and Paul Church on the bluff next to the Grand Palace. It was commissioned by Elizabeth in 1751 and crowned with five gilded domes, as she requested. The church was destroyed during the German occupation in the 1940s but was restored and opened to the public in 2011.

During Peter’s era, the main entrance to the Peterhof estate faced the Gulf of Finland because Peter and most of his guests would have arrived by boat.

Fountain in the Upper Gardens of Peterhof

Neptune Fountain in the Upper Gardens of Peterhof

After a highway leading to the Grand Palace was completed, later generations of royalty shifted the main entrance to the opposite side of the estate (although official guests arriving at Peterhof and the Konstantin Palace these days often use the gulf entrance because they usually come from Saint Petersburg by hydrofoil). When the main entrance moved to the highway side, more impressive fountains were constructed in the Upper Gardens to greet them. These include the Neptune Fountain, and a smaller one with a dragon surrounded by four dolphins.

We did not take time to tour the interiors of any buildings at Peterhof, but no matter; the brilliant gold and white exteriors and the gardens were impressive enough.

Friends sharing the first course at the Alex House

Alex House Restaurant

Borscht with a dab of sour cream

Chicken Kiev. Apparently, “presentation” is not a major concern in the Alex House kitchen

Dessert

Our bus was waiting for us at the highway entrance and took us a few miles to the Alex House restaurant, where our guide had arranged for us to be served an authentic Russian meal. First course was a classic Russian Salad composed of chopped potatoes, chicken, boiled eggs, pickles, peas, and capers mixed with mayonnaise. The second course was soup: borscht, of course, made with beets and cabbage and seasoned with hints of dill and bay leaf; chicken chunks replaced the more traditional beef. The main plate was Chicken Kiev with mashed potatoes, unadorned by any sauce or garnish. (Chicken must be cheap and plentiful in Saint Petersburg right now, but we won’t complain that it appeared in every course at lunch; friends who visited Russia during the late 1980s told us they were served cabbage at every meal, including breakfast.) Dessert was vanilla and chocolate ice cream topped with a little red berry sauce. The food was undistinguished but good, and the small, sun-splashed private room where we ate was charming, but we felt cocooned from interaction with any locals except the wait staff.

The Coastal Monastery of Saint Sergius

On our bus ride back into the city, we passed the Coastal Monastery of Saint Sergius. Founded in 1734, it was well supported by members of Russia’s wealthiest families, who worshipped in its cathedral, confessed to its priests, and were buried in its cemetery. Some nobles sent their daughters and younger sons there to take religious orders. After the Revolution, the Soviets usurped control of the monastery and turned the property into a labor camp; the buildings sustained further damage during World War II. In the early 1960s, the former monastery became a police school; subsequently, the cemetery was desecrated, the cathedral blown up, and several other churches on the grounds destroyed. In 1993, the compound was returned to the Russian Orthodox Church, who reopened the monastery the following year. We didn’t stop to visit, but from the outside, the place appeared to be prospering once again.

Our group waits in the metro entrance while our guide purchases tokens

When we got back into Saint Petersburg, someone in the group asked Marina if we could ride the metro. She assented, and directed our driver to deposit us at the Avtovo station in the Kirovsky District. We admired the grandeur of the architecture while she stood in line to buy tokens, which she then distributed so we could ride the Red Line two stops to the Narvskaya station.

A metro token

We were all impressed with the general cleanliness of the underground as well as with the sumptuous yet stately decor, which featured less-than-subtle holdovers from the height of the Soviet era. When construction of the Saint Petersburg metro system began in earnest in 1949, it was designed to serve as much more than a means of transportation. Metro stations were intended to be “palaces of the people,” decorated with monumental artworks for even the lowliest “comrades” to enjoy. Sculptures and mosaics celebrate workers and students as well as soldiers and statesmen. A less obvious but equally important function of the metro was public safety: the deep tunnels could be used as bomb shelters during the Cold War. We did not realize how far underground we were until we had to take three flights of escalators—rising a total of 52 meters—to get out of the station. (To compare: while some lines of New York City’s Subway run as deep as 55 meters, others are only 15 meters underground.)

Riding the metro gave us a chance to mingle for a few minutes with regular Russians, who seemed little different from metro riders in any other city.

On the metro

Soviet decor in the Avtovo metro station

Molded glass from a local factory decorates some columns in the Avtovo metro station

Sculpture glorifying Soviet farm workers in the Narvaskaya station

On the platform of the Avtovo metro station

Riding one of the three escalators toward exit of the Narvskaya station

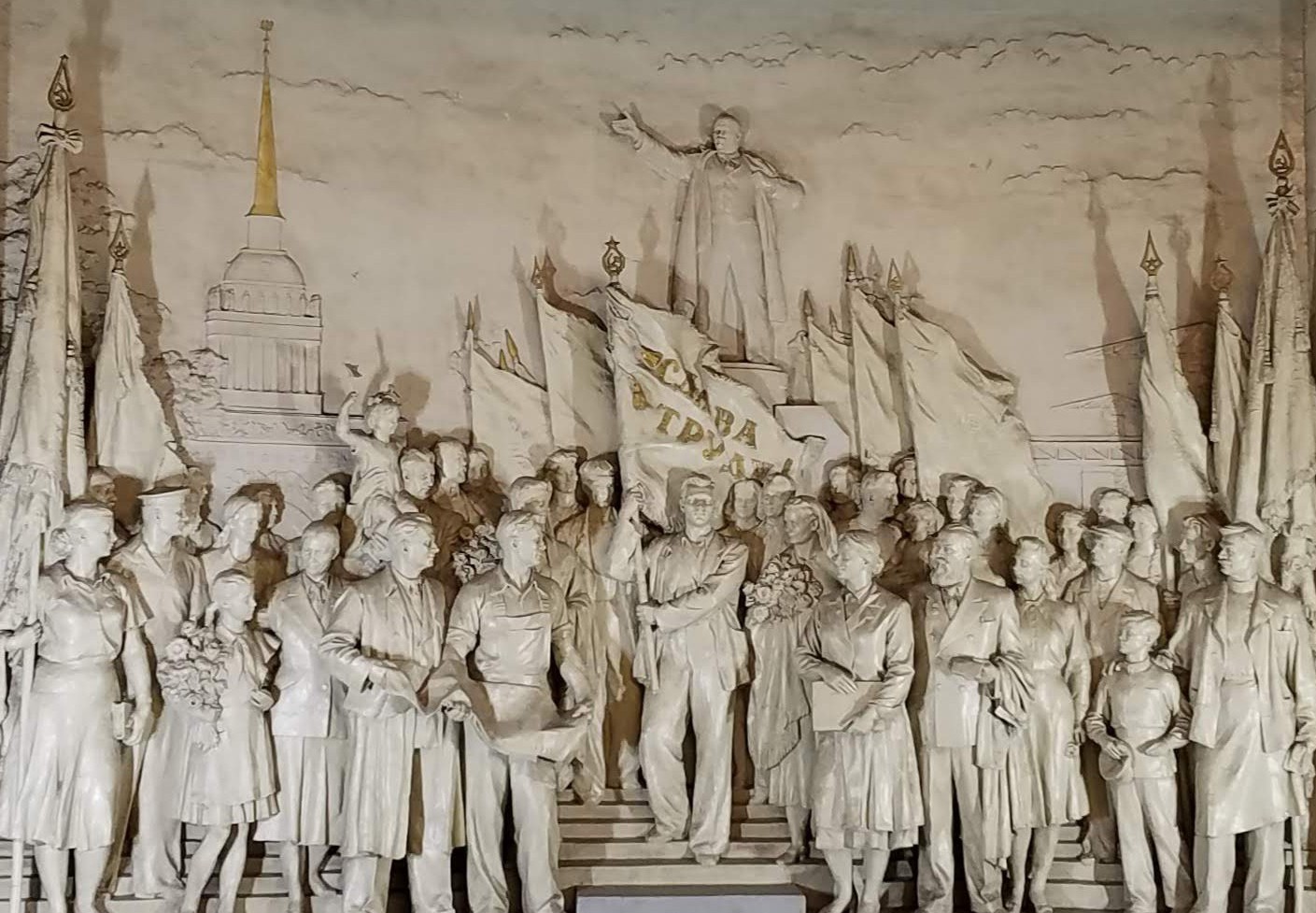

The “glory of work” is extolled in a sculpture in the Narvskaya metro station. The figure at the top is probably Nikita Kruschchev, who was Party Secretary when the metro was built. The building with the gold spire is the Admiralty in central Saint Petersburg

Narva Triumphal Arch

When we emerged from the Narvskaya station, we got a close-up view of the Narva Triumphal Arch, which is very much like the Arc de Triomphe in Paris except that for some reason, it has been painted green. The similarities aren’t accidental: the monument in Paris was commissioned by Napoleon in 1806 to celebrate his victory at Austerlitz; the arch in Saint Petersburg was constructed in 1814 to celebrate the would-be emperor’s defeat by the Russian army. Both arches were originally constructed of wood, but eventually were replaced by permanent stone structures with monumental sculptures honoring a wider array of military heroes.

A tourist boat plies one of Saint Petersburg’s many navigable canals

While driving through Saint Petersburg, we noted other similarities with Paris. Both cities have broad boulevards that radiate from circular plazas; both are graced by stately monuments and well-proportioned classical buildings; and both have height restrictions that prevent the skyline from becoming a jumble of skyscrapers that obscure the architectural beauties of centuries past.

Saint Petersburg University

Some of the architectural beauties we saw as our tour continued this afternoon included the University of Saint Petersburg, where the first Russian Nobel laureate, Ivan Pavlov, and our tour guide were both students (though not at the same time), and the Nikolo-Epiphany Naval Cathedral.

Nikolo-Epiphany Naval Cathedral

Built from 1753-1762 as a place of worship for the city’s naval regiment, the baroque church’s lower level is dedicated to St. Nicholas, an early bishop of a port city in Asia Minor who became the patron saint of seamen. (Although he also is recognized for his habit of secretly giving generous gifts, St. Nicholas is not celebrated as “Father Christmas” in Russia as he is in many Christian cultures.) On the upper floor of the cathedral is the Church of the Epiphany, consecrated by Catherine the Great; it contains several memorials dedicated to the Russian Navy. Nikolo-Epiphany Naval Cathedral is one of only a few churches in Saint Petersburg that continued to function as a religious institution throughout the Soviet era.

Saints Peter and Paul Cathedral and bell tower

One more feature that Paris and Saint Petersburg share is an iconic cathedral located on an island in the city’s major river. In Paris, it’s Notre Dame; in Saint Petersburg, it’s the Cathedral of Saints Peter and Paul. Completed in the early eighteenth century, Peter and Paul is the oldest church in the city, and is especially significant because nearly all of Russia’s czars and czarinas from Peter the Great on down are entombed within it. Although the mutilated bodies of Nicholas II and his wife Alexandra were said to have been dumped down a mineshaft and burned after they were executed by the Bolsheviks in 1918, in 1979 searchers found their remains in a shallow grave near the house where they had been imprisoned. The discovery was not publicly revealed until after the fall of the Soviet Union, but once DNA analysis confirmed that the remains were those of the Romanovs, the last czar and his wife were reinterred in the cathedral beside their imperial predecessors.

The pillars in Peter and Paul Cathedral are “Russian marble” (i.e., they’re painted to look like marble)

The cathedral’s iconostasis

The St. Catherine Chapel within Peter and Paul Cathedral where the remains of Nicholas II and Alexandra and their children are interred

Tombs of Alexander II and Empress Maria Alexandrovna

Tombs of the “Greats” from left to right: Catherine II, Elizabeth I, and Peter I

Peter and Paul Cathedral also boasts the world’s tallest bell tower, at 122.5 meters. When Peter I toured the Netherlands in 1698 and again in 1717, he was impressed with the beautiful music of the carillons he heard there, and thus ordered a set of carillon bells for his new cathedral in Saint Petersburg. (Carillons are distinguished by finely tuned bells that can play melodies, versus untuned bells that simply ring.) Unfortunately, Peter and Paul’s bell tower was struck by lightning and burned down less than forty years after the carillon was installed, and the bells were totally destroyed. Replacements were ordered immediately, but the new bells were not tuned as carefully as the original set. Attempts were made to recast them, but the tuning was still unsatisfactory. In 2001, Peter and Paul Cathedral got an entirely new set of carillon bells from the Netherlands. It comprises 51 bells and has a range of four octaves (in comparison, a piano’s range is about seven octaves). While we waited to go inside the cathedral, we heard the carillon play the tune called “St. Petersburg,” which we know as the melody of “The Lord My Pasture Will Prepare.” Unfortunately, it was evident to us that the carillon still has tuning issues.

Aerial view of the fortress

The Cathedral of Saints Peter and Paul is at the center of the Peter and Paul Fortress, which occupies a small island in the Neva River. Originally built in 1703 to protect Peter the Great’s new capital, the citadel never saw battle until it was attacked in 1917 by Russian rebels seeking to free the political prisoners held there. Indeed, through most of its history, Peter and Paul Fortress served as a place not only to house and train the local regiment, but also to confine enemies of the state. It suffered considerable bomb damage during World War II even though by that time most of the compound had become a museum and historical site rather than a military installation. One building that retains its original function is the mint, founded by Peter I in 1724 and still in operation.

A ramp for the huge cannons that never had to be used to defend the fortress

A guard turret of the Peter and Paul Fortress overlooks the Winter Palace across the Neva River

The mint within the Peter and Paul Fortress, built in 1805, still produces coins and medals

Walking behind the mint

Boarding our mini-bus

The sail-away grill-out on deck

Tony, Katie, Michael, Nancy, Mary-Anne, and NJ

Around 3:30 p.m. we reboarded the bus and returned to the Star Breeze. We had a chance to write and rest for a bit until it was time for the sail-away event, which tonight featured a grill-out on deck. As we left the port of Saint Petersburg, cruise guests feasted on a variety of grilled meats from lamb chops to lobster tails, roast suckling pig, and paella, and then selected from the extensive salad and dessert bars. Better than the food were our views of the city, its bridges, and its wooded islands as we headed out to sea.

A bridge on Saint Petersburg’s high-speed Ring Road, as seen from the Star Breeze on our way out of the harbor

Peter the Great’s original citadel in the Gulf of Finland at the gateway to Saint Petersburg

When everyone had finished eating, tables and chairs were cleared away so cruise directors and crew members could lead guests through some line dances. (We sorely missed Judith, our friend and dancer extraordinaire!)

Ed and NJ comparing playlists

When the dance party ended about 8:00 p.m., most guests migrated to the lounge to continue drinking, but our group of teetotalers ended up in the auditorium, where NJ and Ed were organizing a game of Name That Tune. Here the half-generational gap between the older members of our group and the younger ones made a difference that had never before been an issue among us. First, even though Ed tried to hook up a more powerful speaker to NJ’s phone, the connection failed, and the subsequent lack of amplification made the game difficult for those of us who are beginning to experience age-related hearing impairment.

The “older” generation tried valiantly to recognize at least a few songs from the 1980s

Can you name that tune?

Worse, however, was the generation-based lack of shared musical experience. As representatives of the couples who have been married less than forty years, both NJ and Ed had playlists composed of songs from the 1980s, which those of us who had spent most of that decade either establishing careers or chasing toddlers had been too busy to pay attention to. Neither Michael nor Nancy had been avid radio-listeners in our youth, anyway, preferring classical music (or, Nancy’s case, show tunes) to top-40 fare, so when we were asked to identify songs by Def Leppard or Morrissey, all we could do was shrug. At one point, an exasperated Linda—who is another half-generation older than we are—cried out, “Don’t you at least have any Beach Boys in your playlist?” Nevertheless, it was fun to test our memories, and even more fun to observe Ed and NJ getting so excited about their mutual passion for obscure alternative rock bands from the end of the last century.

The never-ending sunset

Can you name this animal?

We took a stroll around the deck before going to bed, enjoying the gorgeous sunset. The most amazing thing about the sunset is that it was still in progress (i.e. the sky was still pink) when Michael peeked out the window at 1:30 a.m.

As someone who lived and studied in St Petersburg. (Leningrad at that time) I can not get enough of your writing about my favorite city. Love your journal and appreciate your insight into a very different country

Thanks for your endorsement, Tamara! We regret that our stay was so short, because there is so much more there to see and learn.