Michael and Nancy by one of the Land Cruisers

Even though we went to bed late last night and were kept awake for a while after that by a howling dog fight right outside our window, we still had to get up at 6:00 am so we could eat breakfast and be ready to leave by 7:15. As we filled our plates from the extensive buffet (omelettes, crepes, sausages, vegetable curries, all manner of breads and tropical juices) it was a delight to greet friends we hadn’t seen for a while. These include Pam & Eric, who had lived in Cincinnati for several years, as well as Eva & Barry and Jan & Steve, couples from Utah who had been part of our Aegean cruise group in 2017. After quick introductions to Dyrk’s uncle, aunt, and two cousins, and to the four other couples we had not met before, the two dozen of us divided ourselves into groups of four and loaded into Discovery XA’s six specially outfitted Toyota Land Cruisers. Nancy, Michael, Pam, and Eric joined Jim in Edwin’s vehicle; Carol was the fifth passenger with another party.

Pam and Eric

The six-hour drive north from Nairobi to the Samburu National Reserve offered plenty of time for us to catch up with Pam and Eric, as well as to observe a good cross-section of Kenya.

In a country like Kenya and a continent like Africa, confrontation with grinding poverty is unavoidable. The realization that we–Michael and Nancy and everyone else in our tour group–are part of the privileged class who can afford to fly halfway around the world in order to “experience” foreign cultures and exotic wildlife is inescapable–and discomfiting. Whenever our vehicle slows enough to allow photography through an open window, we’re as eager to take photos of people walking along the dusty footpath next to the highway as we are of the passing scenery–but is that rude? Do our subjects regard us as curious and interested, or as exploitative? It’s hard to tell, even when they smile and wave back.

People here walk everywhere, or else use some sort of communal transportation. The most prevalent mode is the matatu, a privately-operated van crowded to the max with people and packages. Though there may be some designated stopping points for these oversized taxis, people seem to congregate anywhere along the side of the road and wait until a matatu with enough room stops to pick them up.

Typical mode of transportation

A third mode of transportation is the motorcycle, which carries both people and cargo. It’s not uncommon to see up to four people piled on one cycle, or a couple of men trying to navigate while balancing four 20-kilo bags of charcoal or some 4’ x 8’ sheets of plywood. Even within Nairobi where most streets are paved, we don’t see many bicycles; outside the city, where roads are deeply rutted with either mud or dust, they are virtually nonexistent. Jim explains that the highways connecting Kenya’s major cities have been paved within the past ten years, thanks to the Chinese. At sites where roads and bridges are under construction, we notice that most bulldozers, excavators, and rollers are marked with Chinese characters, and barricades often sport painted messages like: “Enhancing strong friendship between China and Kenya,” or “China Wu Yi remind you friendly slow down pay attention safety.”

Many shops are painted bright green to advertise Safaricom, Kenya’s dominant communications company

It appears that most commerce in Kenya takes place in rows of ramshackle buildings that are the equivalent of strip malls, though much smaller and without neon. Built of unplastered cinder block, these shops are either unpainted or coated in garish colors, with a door every ten to fifteen feet demarcating a different establishment: cafés, beauty salons, mobile phone agencies, grocery stores.

We also pass a lot of homemade wooden stalls that are probably 4’ x 6’, with two shelves on which the vendor can display his or her wares: fruits and vegetables, clothing, plastic containers, car parts, whatever. If the weather permits and there is space, a cloth is spread on the ground and items are set out for people to view and purchase. However, because today is Sunday, many of the businesses along the highway are shuttered and the market stalls completely empty.

We also pass a lot of homemade wooden stalls that are probably 4’ x 6’, with two shelves on which the vendor can display his or her wares: fruits and vegetables, clothing, plastic containers, car parts, whatever. If the weather permits and there is space, a cloth is spread on the ground and items are set out for people to view and purchase. However, because today is Sunday, many of the businesses along the highway are shuttered and the market stalls completely empty.

Is the structure on the left abandoned or simply unfinished? The church at right is only one of many we passed that appear to be thriving. Also notice the “If you like it, ‘Crown’ it!” sign on the fence. These ads for a major paint company are everywhere

Many of the structures we pass look abandoned: either in total disrepair or never completed. The lack of paint and window glass contributes to that effect, as does a lot of rusty rebar poking up from the walls, but it’s hard to tell whether these buildings are truly vacant. More often than not, we catch glimpses of people moving inside, or see ragged laundry flapping from a row of second-story unglazed windows.

Typical clothing

The clothing most people wear looks like what we put in those yellow bags for the AmVets truck to cart away: tattered, faded, outdated. The concept of putting together a stylish ensemble is meaningless here, where mismatched outfits are the norm for men, women, and children. Keeping anything clean must be a terrific challenge. Most women we saw today had on skirts or dresses, and a very few were wearing shoes with high heels instead of the more common Crocs and sneakers. Is that because it’s Sunday and, in this largely Christian nation, they were on their way to church? Hard to tell.

As a tourist in a country as poor as this one, one must decide how he or she will respond to the poverty. Ignoring it is impossible, as is trying to empathize, because we in the privileged class can have no idea how it feels to live in such conditions. What we can do is sympathize by treating everyone we encounter with kindness and respect, and by supporting the missionaries and other aid workers who devote their time and resources to helping the poor—not just in Africa, but anywhere in the world. We acknowledge that poverty is real, and that the discomfort and anguish we feel is real, but we will not allow our discomfort to color our perceptions and interactions with others—at home or abroad.

During today’s six-hour drive, our guides shared some basic facts about Kenya. The country’s land area is about equal to that of Texas—in other words, big. Jim pointed out that the continental United States could fit inside Africa four times—which makes it a big continent. We had some inking of this while flying here from London: it took roughly three hours to get to the Mediterranean; but then nearly another six to reach Nairobi, which is located just below the equator.

Kenya has a varied terrain. Nairobi is in a fairly verdant section of the country; beyond the outskirts of the city, we saw Del Monte’s extensive pineapple plantations as well as a few coffee and banana groves. Rising into the hill country, the weather became drizzly as we passed made-made forests of eucalyptus trees, used in the paper industry.

Rest and tourist shop

To break up the long drive, our caravan stopped at a store where we could look over a vast array of carved wooden animals, soapstone bowls, batik paintings, bead jewelry, and other popular souvenirs, but we didn’t find anything we couldn’t live without–other than the washrooms.

At Nanyuki, a large town built around a British army base housing 30,000 soldiers, we crossed the equator and passed back into the northern hemisphere. The nearby hills are covered with rows of huge nylon hothouses where roses are grown for shipment around the world.

Semi-arid grasslands of Samburu

By the time we reached our destination–the Samburu National Reserve–we had left the paved highway and had entered the semi-arid grasslands of Kenya’s Rift Valley. The terrain reminds us of the great plains of Kansas and Nebraska, but here the sparse trees and shrubs are not scrub oak and sage, but doum palm and acacia–both of which resemble something from the imagination of Dr. Seuss.

Doum palm

Acacia

The doum palm is notable because it is the only variety of palm with multiple trunks. One variety of acacia grows in the shape of a wide, flat umbrella, providing shade and food for giraffes and elephants; another variety, called the “toothbrush tree,” is spiky with long, wicked thorns. Other shrubs cluster along the Ewaso Ng’iro River, which runs between the Samburu and Buffalo Springs Reserves. The name Ewaso Ng’iro means “brown water”–an apt description of this sluggish stream.

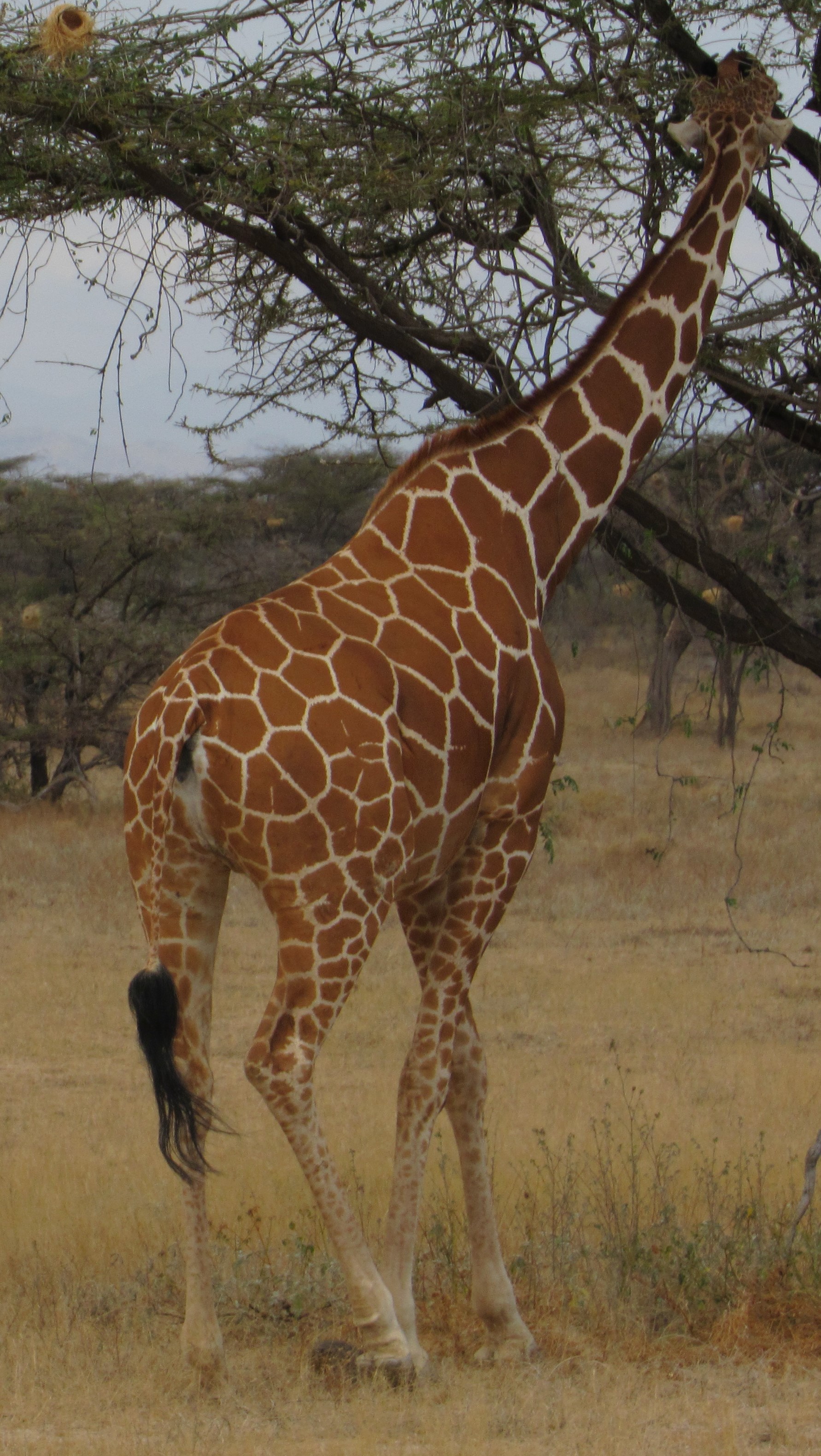

Moments after we passed through the reserve’s entrance gate about 1:15 pm, we were greeted by a “tower” of giraffes (yes, that’s the correct term for a group of those long-necked beasts) and a small herd of zebras. By the time we reached the Samburu Simba Lodge about fifteen minutes later, we had seen a couple of elephants, several graceful gerenuks and oryxes (two varieties of antelope), and some endearingly homely warthogs. Jim and Edwin also pointed out some distinctive birds: white-headed buffalo weavers whose ball-shaped nests decorate the acacia trees, helmeted guinea fowl, and a long-legged secretary bird with a spiky crest that mimicked Miss Liberty’s crown. Our guides had already stopped to pull up the top of the Land Cruiser, so now all of us were standing on the seats, focusing our cameras and binoculars on each new creature we encountered.

Reticulated giraffe

Oryx

Common zebra

Gerenuk

Grevy’s zebra

Secretary bird

White-headed buffalo weaver

Helmeted guinea fowl

Weaver nest

African elephant mother and child

Mother cheetah and three cubs

Cheetah cub

Earlier this summer, when Nancy was feeling particularly frustrated with the limitations of mobile-phone photography, she had suggested that we invest in an actual camera for this trip. Michael decided on a Canon SX530 with a 50x zoom lens. So far, we’ve been really happy with it; it allows us to get decent closeups without being too cumbersome. He also brought along a small gorilla tripod to counteract the effects of his essential tremor (shaky-hands syndrome).

We had just reached the lodge and were starting to unload when we heard excited voices coming over the driver’s CB radio. Edwin asked, “Do you want to go see some cheetahs before lunch?” Pam had already disappeared into the washroom, but the rest of us jumped back into the Land Cruiser and sped off without her, because Samburu’s big cats are not always easy to find. Each of the six Land Cruisers in Discovery XA’s fleet had taken a different route from the park entrance to the lodge, so when one of the drivers spotted a family of napping cheetahs, he alerted everyone else.

Soon all six vehicles had converged around the clump of trees where the cats–a female with four cubs–were curled up in the shade. Our arrival caused the mother to lift her head and take a few strides forward to check us out. Before we left, the cubs, too, had stirred and shifted positions a little, but it was obvious that none of them was ready to get up and run during the heat of the day, so we said goodbye and headed back to the lodge, where the staff had graciously kept the lunch buffet open for us. It includes stations for salads, hot entrees, breads, soup, fruits, and desserts. There is also a manned station where cooks can prepare made-to-order omelettes or custom-cut slices of meat.

Welcome to Simburu

The Samburu Simba Lodge, located within the reserve, overlooks a wide spot in the Ewaso Ng’iro where elephants and waterbucks love to congregate. A variety of brightly colored birds brazenly fly into the covered, open-air dining area to filch food from any unguarded plate. Beyond the adjacent lounge, bar, and pool area are the guest rooms, arranged in apartment-style complexes with six rooms per building.

View from our balcony

Our bottom-floor room

As we finished lunch, Jim gave us our room assignments and handed out keys. Each spacious room features a porch or balcony from which guests can enjoy panoramic views of the river and the hills beyond it.

The vent above our door

Vents made of sticks and plastic mesh near the ceiling on three sides of the room allow air and nature’s background music to come through, but they do a pretty good job of keeping bugs out. Keeping other creatures from entering our rooms is more challenging.

Interior of our room

Bathroom

We were warned that whenever we leave, we had better make sure that our porch doors are securely bolted and the front door locked; otherwise, the vervet monkeys or olive baboons who have figured out how to get past the electric fence surrounding the compound are likely to get in and wreak havoc.

We had only enough time after lunch to get settled in our rooms before the 4:00 “game drive.” Carol encouraged us to go with different drivers and switch passengers frequently, so this afternoon we teamed up with Jan and Steve (from Farmington, Utah) in the vehicle driven by Amos (pronounced Ah-MOSE).

Jan and Steve

Amos

Rather than travel in a pack, each of the six Discovery XA vehicles goes its own way on a game drive. The reserve has a meandering system of defined dirt roads that the drivers try to stick to, but sometimes it seems like they just take off over the stubbly grass in random directions. As they had in the case of the cheetahs, the drivers use their phones and CB radios to share information about significant animal sightings, constantly chattering with each other in their native Kikuyu. (All our drivers belong to the same tribe, which is the most populous among the forty-three in Kenya.)

Impala buck and two does

One of the first species we stopped to observe this afternoon was a family of impalas: a dominant male, a handful of does, and several young. Amos explained that the dominant male has exclusive mating rights, but may be challenged at any time. We watched some young males having fun sparring with each other, but recognized that the skills they were honing would later help them obtain and protect their own families. Other adult males hang out in bachelor groups until they can mount a successful challenge–or until they fall prey to a big cat.

Male Somali ostrich

A couple of ostriches we tried to approach became too skittish to photograph, but it was fun to watch them run on their long legs. Ostriches live in groups with one dominant male and one dominant female. These take charge of building a nest and hatching the brood for the whole group. Nondominant females lay their eggs in the same communal nest, but the head hen makes sure that her own eggs are kept in the center where they can be better protected. She sits on the nest during the day, her variegated grayish-brown feathers blending into the color of the surrounding ground; the black-feathered cock takes night duty. Apparently, the big birds hope that predators will mistake their sitting forms for termite mounds.

Termite mound

About 90 minutes into our evening drive, Amos got word that someone had spotted a leopard in a thicket near a muddy trickle known as the Isiolo River, so we wheeled about and headed in that direction as quickly as we could.

Leopard hiding in the thicket

Though we kept watch for nearly an hour, occasionally moving–along with at least a dozen other safari vehicles–to different viewing positions, we were never quite sure whether the shadow we saw creeping through the shrubbery was the leopard or not. Not until nearly 6:30 pm did the elusive cat decide to leave the thicket and stride into the open. We followed him long enough to get a few photos, but the sun was getting low in the sky and we knew that the staff back at the lodge would be expecting us for dinner. Amos said that we were lucky to see a leopard so soon after arriving because sightings in this reserve are fairly rare.

Leopard

Buffet

Desserts and fruit

Only a few other guests are currently staying at the Samburu Simba Lodge, so we didn’t have much competition at the buffet and more than half of the dining area was empty tonight. Carol told us that the Samburu Reserve’s distance from Nairobi (350 km) makes it a less-attractive option for tourists than the parks farther south. That’s fine with us!

After dinner, still struggling to adjust to a new time zone and knowing that our next game drive is scheduled to begin before sunrise tomorrow, most of the group retired to our rooms. The day had been hot in Samburu and, with doors firmly shut against monkey/baboon incursions, the air in our rooms was oppressive. Normally, the generator that supplies electricity to the whole lodge complex shuts off between 10 pm and 5 am, so all of us were grateful that Eric’s medical need for power to run his CPAP device kept the juice flowing to our ceiling fans as well; otherwise it would have been a very uncomfortable night.

Sunset in Samburu

Leave A Comment