“Let’s go see the Pink and White Terraces,” Eva had said when we began planning our next Monday excursion. We hadn’t heard of the Pink and White Terraces, so we asked for a description.

“They’re an amazing crystal formation on a lake near Rotorua. They’re very famous,” Eva had assured us.

“Sounds great,” we said. But when we googled “Pink and White Terraces NZ” to learn more about them, we were dismayed to find out that the terraces no longer existed—and hadn’t since the volcano on which they were located erupted in 1886. We tried to break the news to Eva very gently.

“Oh, I know they’re gone,” she said. “But it would be interesting to see where they used to be. It’s still an active volcanic area, with geysers and mudpots and things like that.”

As it turned out, a visit to the no-longer-extant Pink and White Terraces near Rotorua was definitely interesting and worth the two-hour drive.

Along the way, we rued the yellowed, drought-stricken landscape, and wondered whether the cows were getting tired of eating stiff, crunchy grass. “This is so unusual,” Barry remarked. “I’ve never seen the countryside look this brown before.”

Lake Tititapu (Blue Lake)

Nevertheless, the scenery around our first stop was gorgeous. Lake Tititapu and Lake Rotokakahi (more prosaically called Blue Lake and Green Lake by the Pakeha) both formed about 13,000 years ago. Tititapu occupies a collapsed volcanic crater and is the smaller of the two, with a surface area of about half a square mile. The Maori name refers to a sacred greenstone neck ornament lost in its waters by the daughter of an ancient Maori chief. The English name refers to the color (duh), which appears brilliant blue from a distance due to the reflection from its white rhyolite and pumice bottom. Tititapu is a popular recreation area even though the water temperature is quite cold. It has no visible outlet, but the water remains clear because it flows into neighboring Lake Rotokakahi via an underground river.

Lake Rotokakahi (Green Lake, which looked blue to us)

Rotokakahi is three times the size of and 70 feet lower than its companion. As its English name implies, it appears green from a distance, and does so because it is relatively shallow and has a sandy bottom. Water from Rotokakahi flows from a small stream into Lake Tarawera, 300 feet lower in elevation and about two kilometres to the east. Rotokakahi’s Maori name refers to the shellfish that were plentiful in the lake until 1886, when nearby Mount Tarawera erupted (more on that in a moment). No swimming, boating, or fishing are allowed on this lake, which is closed to the public because the Maori consider it sacred. Motutawa, a small island in Lake Rotokakahi, is the burial ground of numerous ancestors of the Tuhourangi iwi (tribe), as well as of a young Ngapuhi chief named Paeoterangi and his party, who were killed on the island in 1822 as revenge for the death of a Tuhourangi kinsman.

Another type of burial ground was our primary destination for the day: the “Buried Village” of Te Wairoa. Te Wairoa is only one kilometre east of Lake Rotokakahi, but reaching it requires a 34-kilometre trip around the volcanic area into the city of Rotorua, and then back. Founded by Anglican missionaries in 1844, Te Wairoa had grown from a humble village to a thriving resort for European tourists by 1886. The story of its rise and sudden demise is told in the Buried Village Museum and archaeological site, and it’s a fascinating tale.

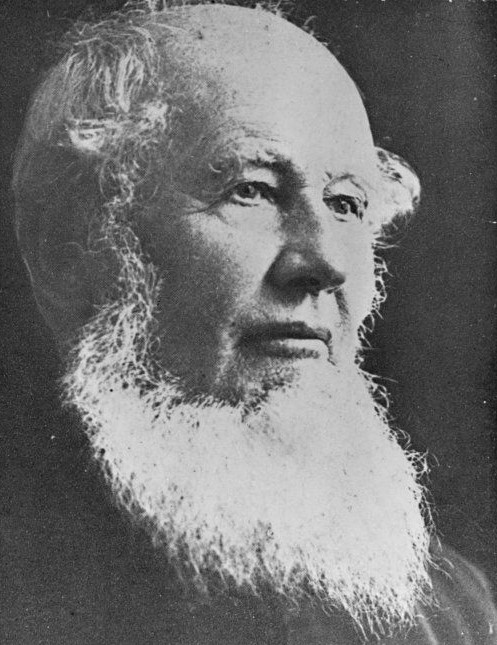

Seymour Spencer

The story begins with a devout Quaker couple from Illinois. Shortly after Seymour Spencer and Ellen Stanley were married, they decided to fulfill a lifelong dream of becoming missionaries to the South Pacific. In 1840, they traveled to England for training with the Christian Missionary Society, which was sponsored by the Church of England. In 1842, the Spencers set sail for Auckland, where Seymour was ordained as an Anglican minister. After short stints in Taupo and Rotorua, he and Ellen opened a mission on the Te Wairoa stream in 1844. Over the next few years, the Spencers taught their Maori converts to cultivate wheat (having not yet learned that the damp climate was not well suited for that type of grain). Along with a chapel, the mill they built became the center of a European-style village.

Before we go on with the history of Te Wairoa, we want to mention that the Spencers were married in Quincy, Illinois, in 1839, less than a year after members of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints crowded into Quincy when they were forced out of the neighboring state of Missouri by the governor’s extermination order. It is likely that the Spencers were among those who offered food, shelter, and compassion to the destitute Saints who had left behind everything they owned in their rush to escape violent mobs. Nancy’s second- and third-great-grandparents were among those who had to flee, so she is especially grateful to the people of Quincy who cared for them during that winter and helped them get back on their feet before they moved to the area that became the city of Nauvoo. She never expected to find such a connection with her own ancestors here in New Zealand.

Te Wairoa Hotel, circa 1880

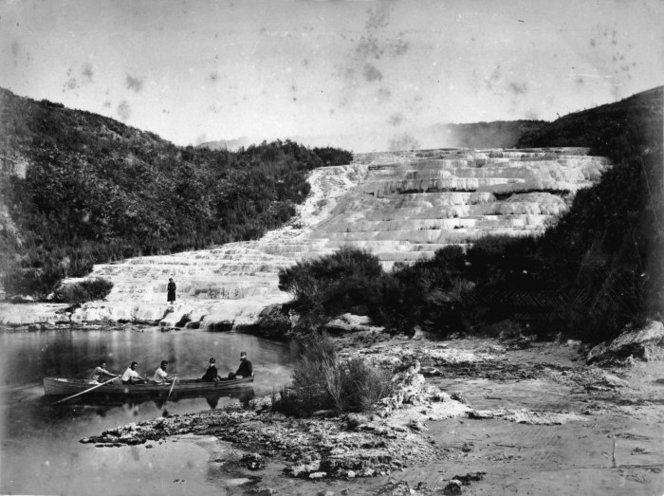

Terraces were accessible by canoe

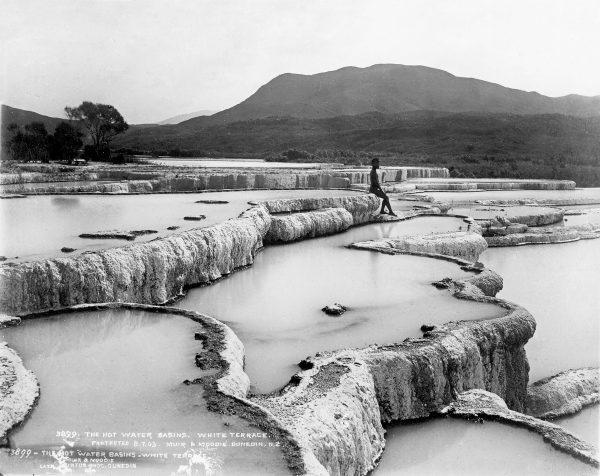

Hot-water pools formed on the terraces

But back to Te Wairoa. During the time when the Spencers were in England, a German scientist named Ernst Dieffenbach was in New Zealand, accompanying a surveying party on an expedition to the volcanic area of Rotomahana and Tarawera. He was thus one of the first Europeans to see the fabulous Pink and White Terraces, a series of crystalline steps descending into Lake Rotomahana from the slopes of Mount Tarawera. Created by silica-laden runoff from hot geysers, the terraces formed a fantastic staircase of pastel pools spilling over with steaming water. Diffenbach’s description of the terraces in his 1843 book, Travels in New Zealand, created a sensation in Europe, and before long, well-heeled travelers began flocking to a site some were calling “the Eighth Wonder of the World.”

A visit to the Pink and White Terraces was not an adventure for the faint of heart. Beginning with several months’ sea passage to Auckland, the trip continued by steamer ship to Tauranga, followed by a 63-mile overland crossing via bridle track to Ohinemutu on Lake Rotorua, and then by a 10-mile coach ride to Te Wairoa. There travelers lodged in one of the two hotels built for such visitors—much to the consternation of the Spencers, who watched as their once-quiet agrarian community transformed into a bustling tourist town and many of their humble Christian converts into avid capitalists. Fed up with the gambling, drinking, and carousing of road workers who also frequented the town, Reverend Spencer decided to close the mission in 1870 and left.

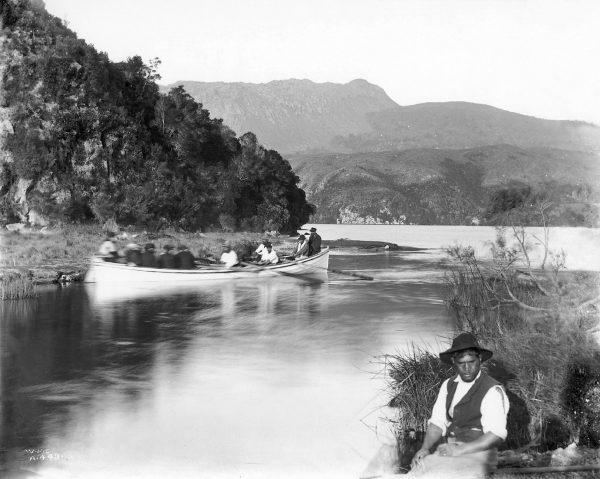

Maori tour guide Sophie Hinerangi

Traveling by canoe to the terraces

Once in Te Wairoa, tour parties would hire a guide (usually Maori) to take them across Lake Tarawera by canoe, and then lead them on foot over the rocky hill on the opposite shore to the swampy banks of neighboring Lake Rotomahana. There they might be served tea and sandwiches before taking a dip in the pools of steaming mineral water cascading down the terraces. (Nancy and Eva tried to imagine making this journey while wearing high-heeled, slippery-soled leather boots and ankle-length woolen skirts over multiple petticoats, as we saw pictured in the museum. The thought boggles the mind.)

But Te Wairoa’s career as a world-class tourist destination was shortlived. Just after midnight on 10 June 1886, a series of increasingly strong earthquakes shook the area. Around 2:00 a.m., the first of Mount Tarawera’s three peaks—the Wahanga Dome—erupted directly across the lake from Te Wairoa. The other two peaks followed in fairly quick succession. The violent explosions split the mountain, creating the eleven-mile-long Waimangu Volcanic Valley (which we describe in a blogpost from our first trip to New Zealand in 2014). In addition, the eruption completely transformed the size and configuration of every lake in the area. Of particular note is the impact on Lake Rotomahana: its area was increased nearly tenfold by a crater a hundred feet deep, engulfing the Pink and White Terraces.

For many years, most people believed that the terraces had been completely destroyed. However, a team of researchers mapping the floor of Lake Rotomahana in 2011 discovered a submerged set of silica tiers similar to the famed terraces and began claiming that these were indeed the former “Eighth Wonder of the World.” Eventually that claim was debunked, as further study showed that the crystal formations found underwater in 2011 were similar to but older than the Pink and White Terraces, and that they had always been submerged. So, once again it is generally accepted that the eruption of Mount Tarawera completely destroyed the Pink and White Terraces, and no amount of wishful exploration will bring them back.

Hinemihi marae where townsfolk were sheltered during and after the earthquake

The destruction of the terraces, the expansion of Lake Rotomahana, and the creation of the Waimangu rift were not the only changes wrought by the volcano’s explosions. Hot mud, boulders, and clouds of ash spewing from Mount Tarawera buried the village of Te Wairoa under a layer of ash and debris nearly two meters deep. Seventeen people were killed, but most residents were able to escape, taking refuge in Hinemihi, the Maori marae farther up the hill.

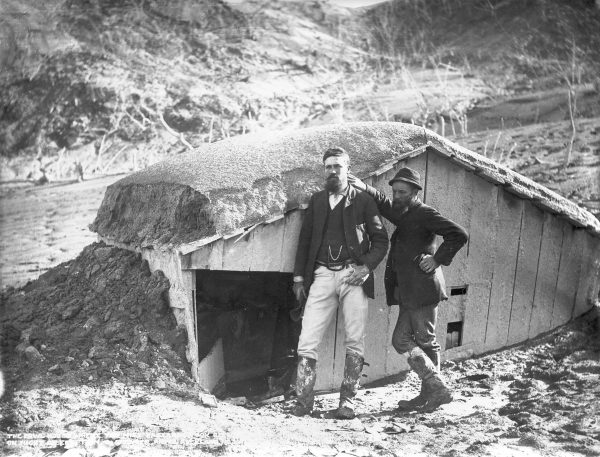

Surveyors Per Emil Henrik “Harry” Lundius (Barry’s great-grandfather) and John Cunningham Blythe in front of the henhouse that saved their lives

Other survivors included a pair of surveyors who happened to be staying in Te Wairoa on the night of the eruption. They ran out of the collapsing hotel and took shelter in a chicken coop. These two were of particular interest to us, because one of them was Barry’s great-grandfather. (But for that chicken coop, Barry wouldn’t be here, and without Barry, we wouldn’t be here in New Zealand.)

Fifty years after the eruption, the grandson of Seymour and Ellen Spencer attempted to revive Te Wairoa as a tourist destination, building tearooms and another hotel, but without the lure of the Pink and White Terraces, the enterprise was not very successful. Eventually, he just abandoned the site. In 1931, a family who had immigrated from England several years earlier decided to buy the property and began to excavate the buried village. Violet Smith restored the tearooms and opened for business while her husband, Reginald, and their two sons carefully unearthed the most significant ruins, preserving the artifacts they dug up. Vi’s fine teas and homemade scones with blackberry jam began attracting tourists back to Te Wairoa when they came to the area to see the Waimangu geysers. The Smiths found that the same tourists were curious to see what was left of the buried village, so after son Dudley returned home from military service in World War II, they decided to open their excavations for public tours. Subsequent generations of the Smith family have kept the business going, building a museum in 1999 to display salvaged artifacts and tell the story of Te Wairoa’s growth and tragic destruction.

The Buried Village Museum and tearoom today

We spent about an hour in the museum, not only looking at the displays but also noting how all the historical information was presented, comparing and contrasting with the museum at the Matthew Cowley Pacific Church History Centre. The Buried Village Museum is a little smaller than ours but probably has more actual artifacts, although their histories are not as varied as those of our items because they all came from the same place and date from approximately the same time. Both museums are text-heavy, requiring visitors to do a lot of reading to really appreciate the story they’re trying to convey, but ours has more electronic interactive activities (although not as many as we would like). The main difference between the two is that the Buried Village Museum seeks to sensationalize the story of one dramatic event, whereas the purpose of the MCPCHC’s museum is to present an ongoing history of the Latter-day Saints in the Pacific and instill greater appreciation for the heritage of that faithful community—and to create an atmosphere that allows visitors to feel the love of the Lord for those people and for themselves.

Traditional carved lintel at the entrance to the museum

Display of furnishings, dishes, and even clothing salvaged from the ruins of Te Wairoa

Lunch on the tearoom patio

When we were done perusing the museum, we were ready for lunch on the tearoom’s terrace. Back in the 1930s, Vi Smith probably didn’t serve her customers roasted vegetable quiche or feta and kumara frittata, but we suspect that Barry’s giant, featherlight scone with cream and the blackberry jam that came with it were made from her recipes. No doubt the generous square of superior carrot cake Michael was served (and generously allowed the rest of us to taste) also would have made Vi proud.

During the rest of the gorgeous afternoon, we strolled down the footpath through the partially excavated ruins of Te Wairoa. Placards along the trail present the history of the village and its former inhabitants, and a series of “letters home” from a fictional English visitor telling about the night of the volcanic eruption and its aftermath. As we followed the narrative, we tried to imagine what that experience must have been for people like her—and for Barry’s great-grandfather.

The village of Te Wairoa, now an archaeological site

Remains of a mill

The blacksmith shop

The one-room whare of the village tohunga (holy man), Tuhotu Ariki, which collapsed on him when Mount Tarawera erupted. Villagers distrusted the tohunga and kept their distance, thinking that the strange old man had used magical powers to cause the calamity. It was four days before he was pulled from his ruined home, alive but not well. He died a few weeks later, purportedly at the age of 110.

The cellar of the Rotomahana Hotel contained crates of wine and spirits that were found intact when the site was excavated in 1983

Vestige of one of the hotel’s two corrugated iron water tanks,. Formerly elevated above roof level, the tanks provide evidence that the hotel offered its guests the luxury of running tap water in an era when most villagers had to fill their buckets from the stream

Michael examines a display of items found in a hotel employee’s house

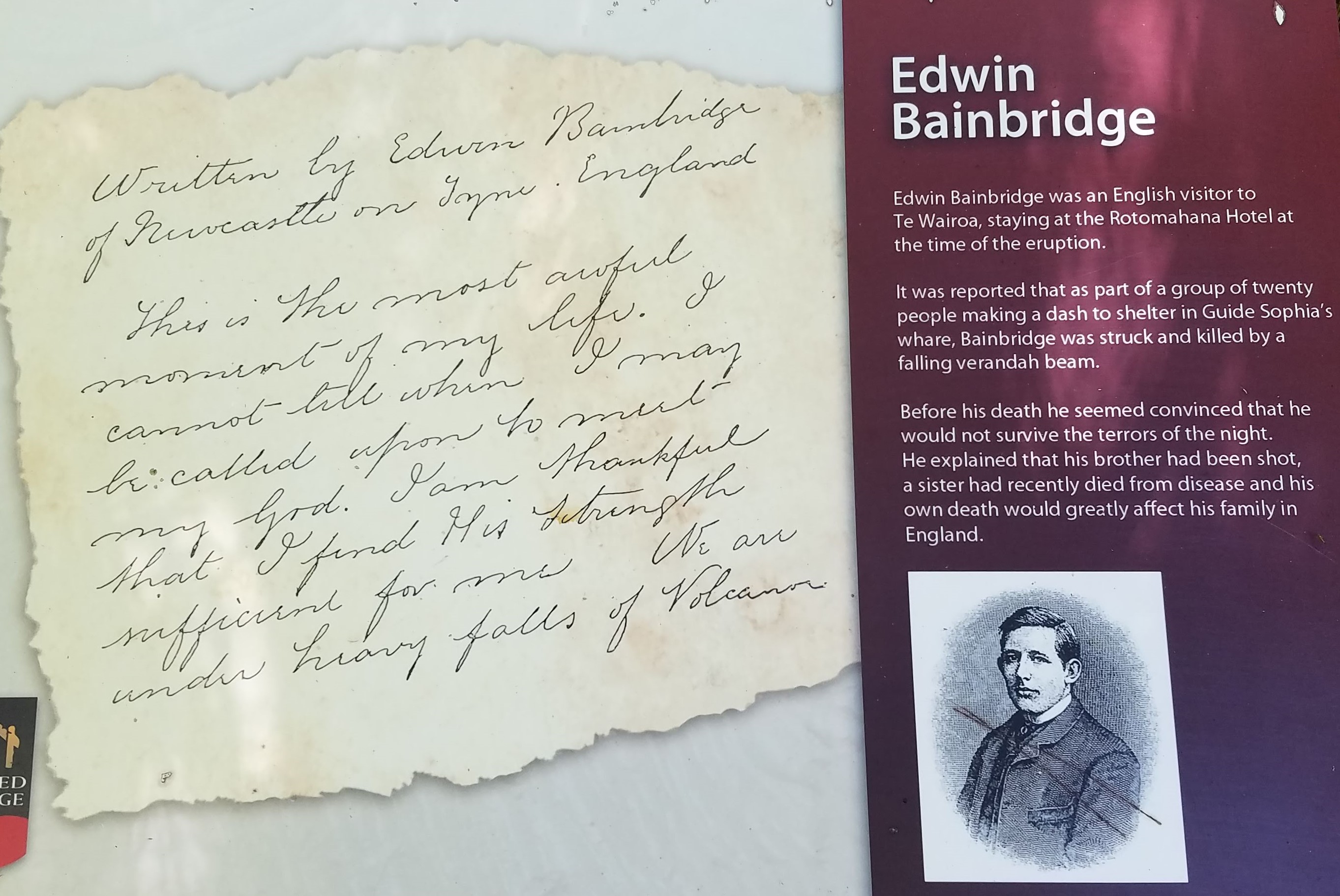

Edwin Bainbridge, a young visitor from England who was staying at the hotel, recorded a premonition of his own death in his journal on the night of the eruption. “This is the most awful moment of my life,” he wrote. “I cannot tell when I may be called upon to meet my God. I am grateful that I find his strength sufficient for me.” As Edwin and other guests tried to escape the burning hotel, he was struck and killed by a falling beam

Lone surviving pine tree planted as a memorial to the Smith brothers

The footpath continues through the bush beyond the village to a memorial to the Smith brothers, who each planted a pine tree here in 1939 before going off to serve in World War II. Basil, Reginald and Violet’s elder son, enlisted in the Royal New Zealand Air Force and was killed in a plane crash in Ceylon. Dudley joined an army battalion and went missing during a “horrendous” battle in Greece, but survived to continue the fight in Libya—and then to continue developing the family business at Te Wairoa.

Wairere Falls comprises three successive falls, the tallest of which is about 30 meters

Michael following the Te Wairoa stream into the bush toward Wairere Falls

The view from the hill behind the village of Te Wairoa

After a short hike through the bush behind the village to see Wairere Falls and the panoramic view from the hilltop, we drove up the road to Stoney Point Reserve on Lake Tarawera, where we could see the now dormant volcano in the distance on the other side.

Lake Tarawera and the dormant volcano

We gladly accepted this invitation from One Road ice cream shop in Tirau

Our drive back to Hamilton just happened to take us through Tirau, where a couple of weeks earlier we had found One Road, the place that sells what just might be the best ice cream in all of New Zealand. Of course, Barry and Michael felt compelled to verify that brash claim with another sample. No doubt this research project will continue for many more months.

Leave A Comment