The Matthew Cowley Pacific Church History Centre is closed on Sundays and Mondays. We honor Sunday as the sabbath, so we try to avoid doing anything that might be classified as work (other than necessary tasks such as basic food preparation and cleanup) or that require someone else to work (other than vital services such as medical care and police), so our Sunday after-church outings tend to be simple and focused on the fascinating and beautiful creations of God and humankind. On Mondays, however, we have no such religious restrictions and generally have more time to travel, so we are using those days to go farther afield.

The Matthew Cowley Pacific Church History Centre is closed on Sundays and Mondays. We honor Sunday as the sabbath, so we try to avoid doing anything that might be classified as work (other than necessary tasks such as basic food preparation and cleanup) or that require someone else to work (other than vital services such as medical care and police), so our Sunday after-church outings tend to be simple and focused on the fascinating and beautiful creations of God and humankind. On Mondays, however, we have no such religious restrictions and generally have more time to travel, so we are using those days to go farther afield.

Our first Monday in New Zealand was consumed with business such as setting up our phone and broadband accounts, and shopping for the housewares we needed to make our flat more livable: towels, bedding, clothes hangers, organizer bins, lightbulbs (for some reason, about half the fixtures in the flat had burned-out bulbs), and a lot of plastic containers with tight lids to keep the flies, moths, and cockroaches out of our food. (Remember: we live in multiplex housing, and our windows have no screens.) By the next Monday, however, we were ready to use our hybrid vehicle to see a part of the country we had not previously visited.

The Firth of Thames

The first destination we chose was the town of Thames on the Coromandel Peninsula, about sixty miles from Hamilton. The peninsula forms the western boundary of the Bay of Plenty and the eastern boundary of the Firth of Thames, both parts of the Pacific Ocean on the eastern side of New Zealand’s North Island. About fifty miles long and twenty-five miles wide, the peninsula is basically a mountain range with peaks that rise up to 3,000 feet from a narrow strip of beach around its perimeter, and we had heard that it offered gorgeous views all along its shoreline.

We didn’t get started very early because we had scheduled a family video chat at 10:30 that morning, when it was still Sunday afternoon in the States. (For once, Nana and Grandpa were the center of interest because even our grandchildren were eager to see our new digs, so we gave them a virtual tour and told them about our first week at the Centre.) By 11:30 we had departed, taking a packed lunch to eat on the way.

Thames

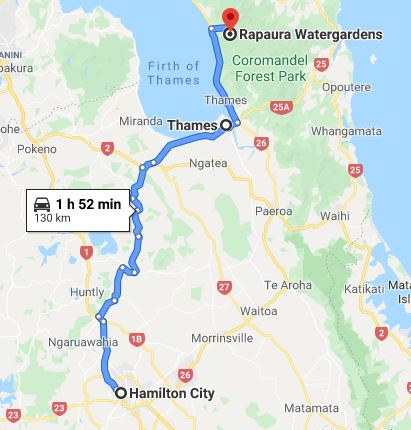

Following Google Maps’ shortest route to Thames took us along a lot of narrow roads of the type we describe as “yellow” and “white” (based on the way they appear in our atlas), through country devoted to dairy farms and cattle grazing. We met very few other vehicles until we got fairly close to Thames, which is right at the base of the peninsula’s western coast. (The name of the town is pronounced “Tems,” same as the river that runs through London.)

The beach resort greets visitors with a big sign that says: “Thames: Our Heritage Is Gold.” This is quite literally true: the people who developed this area did not come to enjoy its sandy beaches nor its scenic views, but because in 1867, gold was discovered within quartz veins running through the soft earth of the bluffs overlooking the shore. Speculators migrated to the area to stake their claims, including droves of coal miners from Cornwall. By 1900, Thames had become the largest city in New Zealand.

Entrance into the Gold Mine Experience

We had had no idea of this piece of NZ history until we visited The Gold Mine Experience on the site of the former Golden Crown Claim. The tour included a short descent into one of the mine shafts, and demonstrations of the big, clunky machinery used to extract the precious metal from quartz hauled from underground.

Inside the mine shaft

The guide explained that one ton of quartz could yield 54 ounces of gold, and told us that at their peak, the area’s mines produced two tons of gold a month. She must have meant that the mines processed two tons of quartz a month, because we read elsewhere that the official total gold production for the Thames-area mines from 1867 to 1953 was 2,327,619 ounces, with a monetary value of $845 million. Though not as jaw-dropping a figure as two tons a month, the amount of gold produced is still significant when you consider that nearly 45,000 tons of quartz had to be dug out, brought to the surface, crushed, sifted, and chemically treated to obtain that yield, and that most of the work was done with hand tools and crude machinery. The region also produced nearly as much silver as it did gold, using the same primitive methods.

Machinery used to crush the quartz

Machinery for sifting out detritus

Tools used to test the purity of the gold

In what had been the office of the Golden Crown Claim, we watched a video version of film footage shot in 1949 at the Martha Mine. It had been the area’s most productive mine in its heyday, but by the mid-twentieth century the veins of gold and silver were played out, and the facility closed in 1953. To our eyes, working conditions at that time didn’t look much better than what we imagine they must have been in the late 1800s: none of the miners were wearing any personal safety equipment—no helmets, no face masks, no hearing protectors. We were shocked to learn that they earned less than a dollar a day. Moreover, they were highly susceptible to lung disease and complications of exposure to the cyanide solution used to extract gold from the crushed rock; more miners died from illness than from accidents.

Kauri forest

Another of the Coromandel Peninsula’s natural resources that was exploited in the nineteenth century was its kauri forests. Kauri is a native hardwood that is perfectly suited for the lumber industry because of its ease of working, durability, and resistance to warping. Shipbuilders favored it for masts and spars because of its straight, even grain and lack of knots. Carpenters like it because it saws and planes easily and holds nails well. It’s also a beautiful wood, golden tan with attractive grain patterns, so furniture makers and artisans appreciate it, too. We had noticed kauri right away in the woodwork of the church building we attended on our first Sunday in New Zealand, but at the time we didn’t know what kind of wood it was.

The reception desk at our museum is made of kauri

Not only the abundance of kauri trees on the Coromandel but also the peninsula’s terrain contributed to the success of the timber industry there. Creeks that ran swiftly downhill from highland forests through deep valleys to the sea were augmented by driving dams engineered to send great quantities of kauri logs to the coast, where they were milled and shipped to other parts of the country and the world. But, like its metallic counterpart, golden kauri wood turned out to be a limited resource. Demand for lumber outpaced the forests’ ability to regenerate, and by the 1920s the Coromandel had been all but stripped of its kauri trees. Eventually, some of the lower-lying forests were replaced with fruit orchards and dairy farms, which continue to provide the area with economic stability. In the past hundred years, the peninsula’s steep hillsides have been allowed to return to their natural state, and the resulting stunning contrasts between green bushland, rocky shores, and blue water has attracted tourists, artists, and retirees to the region.

View along the Tapu-Coroglen Road

Rapaura fern bog

Rapaura lily pond

From Thames, we drove about 20 km up the west coast to the town of Tapu and then took a right, heading east across the peninsula on the Tapu-Coroglen Road. Another 6 km of winding up the mountain took us to Rapaura Watergardens, the creation of a couple named Loennig who decided to turn 64 acres of regenerating bush and pasture land into an idyllic garden retreat during the 1960s. The Loennigs have passed on, but Rapaura’s current owner retains their vision for the estate: “The best Garden is a well-kept wilderness.”

Waterfall at Rapaura

Stream at Rapaura

Rapaura is open to the public for leisurely strolls along its 2.5 km of shady paths, and can be rented for “functions” such as weddings. As its name implies, water is the centerpiece of the gardens, with fourteen ponds of all shapes and sizes that host water lilies in a variety of colors, and a meandering stream that culminates in a waterfall. Native vegetation surrounds the water features: palms, ferns, and other bush shrubs, but there are also displays of hydrangeas, irises, and orchids—as well as many small sculptures and plaques bearing thoughtful quotations. We made a mental note to return in the spring when the rhododendrons and azaleas are in bloom.

The Fodor guide had recommended Rapaura’s onsite cafe, but we didn’t visit at mealtime, and anyway the cafe happened to be closed for carpet cleaning when we arrived. The proprietor apologized for the inconvenience, and was happy to offer us a wedge of delicious, buttery shortbread free of charge. When we returned from our walk, he had two glasses of chilled water waiting for us—a greatly appreciated gesture, because when we came out of the shady bush, the bright sunlight was hot.

The giant Square Kauri

“Are you going on to see the Square Kauri?” our host asked. “It’s only a few more kilometres up the road.” We had considered going because Fodor had mentioned the kauri, too, although the guidebook had described the road to get to it as “not for the faint-hearted” and we weren’t quite sure what that meant. The man at Rapaura allayed our fears, explaining that although most of it was “metal” (the Kiwi term for a gravel road) it wasn’t much steeper and winding than the one we had already traveled. “You’ll cross two one-lane bridges,” he said. “As soon as you cross the second one, there’s a small parking area on the left, and the steps up to the tree are across the road on the right. You can see the tree from the road, so be sure to take a look up before you climb the steps so you can see how tall it is.”

Steps to the tree

So what, exactly, is the Square Kauri? It’s a 1,200-year-old tree, the largest in New Zealand by volume, although not the tallest. We’ve already described the kauri in terms of its value as timber wood, but while living, it’s a beautiful, tall tree with smooth bark and small, narrow leaves. It is New Zealand’s equivalent of a giant redwood, living for hundreds of years and growing up to 150 feet tall and 35 feet in diameter. Sadly, only a few stands of old-growth kauri remain, mostly in mountainous terrain too inaccessible for the timber companies to have bothered with.

The Square Kauri up close and personal

Compared to the trees around it, this particular specimen was massive, and its enormity became even more apparent after we crossed the road and climbed the 157 steps to its midsection: 30 feet in diameter. However, at 133 feet tall, this particular kauri is only New Zealand’s fifteenth in terms of height. We were dismayed to learn from a sign at the viewing platform that these marvelous trees are endangered by kauri dieback disease, a fungus that lives in the soil and damages the tree’s ability to move nutrients and water through its tissues. The sign advised us to thoroughly clean our shoes before entering and after leaving the surrounding tracks to avoid spreading the disease to other areas, because even a pinhead-size bit of soil may contain enough fungus spores to eventually kill a giant like the Square Kauri.

Gastronomics

Catch of the Day: gurnard

On our way home, we stopped in Thames for a nice dinner at Gastronomics that began with garlic bread dripping with butter and only got better. Nancy ordered the catch of the day: grilled gurnard (a type of white fish that was new to us) with red capsicums (peppers) and tangy plum sauce, served on a bed of sauteed spinach with a baked potato “stack” (similar to potatoes Lyonnaise). Michael had roast free-range chicken with black currants, served with potatoes, spinach, and a mixture of perfectly sauteed vegetables.

Molten chocolate cake with mango ice cream and berry compote

For dessert Nancy had a vanilla sundae with mango and passionfruit sauces, while Michael savored his molten chocolate cake with mango ice cream and a compote of boysenberries and blueberries.

Mango and passionfruit sundae

About halfway back to Hamilton on the same deserted backroads we had traversed that morning, Nancy realized that the lack of traffic presented a good opportunity to try driving on the left side of the road. She did remarkably well at keeping the car centered in the lane (harder than it may look), but she was ready to cede the wheel back to Michael just before reaching the roundabout outside Hamilton that put us back onto the four-lane highway and into city traffic.

Leave A Comment