Our trips to Kawhia to visit the museum and then to dig for pipis took us through the foothills around Mount Pirongia, the highest peak in the Waikato region at 959 meters (3146 feet). Only 30 kilometres southwest of Hamilton, the mountain is clearly visible from many vantage points in the city, and its looming presence has figured in local legends for centuries. Most people agree that the mountain was given its full name—Pirongia te aroaro o Kahu—by Rakataura, tohunga (wise man) of the waka Tainui, but there is less consensus about what the name means. By some accounts, it means “the health-restoring purification of Kahu,” referring to Rakataura’s ritual healing of his wife, Kahurere. Other sources say the phrase means “the fragrant presence of Kahu.” An entry in the Encyclopedia of New Zealand published in 1966 interpreted the phrase as “like a bad smell,” which must not have gone over well with Kiwi readers, because the revised current edition of the Encyclopedia states that the name of the mountain means “the scented pathway of Kahu,” but claims that the Kahu named was not Rakataura’s wife, but another ancestor named Kahupekapeka.

Our trips to Kawhia to visit the museum and then to dig for pipis took us through the foothills around Mount Pirongia, the highest peak in the Waikato region at 959 meters (3146 feet). Only 30 kilometres southwest of Hamilton, the mountain is clearly visible from many vantage points in the city, and its looming presence has figured in local legends for centuries. Most people agree that the mountain was given its full name—Pirongia te aroaro o Kahu—by Rakataura, tohunga (wise man) of the waka Tainui, but there is less consensus about what the name means. By some accounts, it means “the health-restoring purification of Kahu,” referring to Rakataura’s ritual healing of his wife, Kahurere. Other sources say the phrase means “the fragrant presence of Kahu.” An entry in the Encyclopedia of New Zealand published in 1966 interpreted the phrase as “like a bad smell,” which must not have gone over well with Kiwi readers, because the revised current edition of the Encyclopedia states that the name of the mountain means “the scented pathway of Kahu,” but claims that the Kahu named was not Rakataura’s wife, but another ancestor named Kahupekapeka.

Mount Pirongia

Whatever its name means, Mount Pirongia arose from a series of volcanic eruptions 2.5 million years ago that left three distinct peaks. Such geothermal activity has long since ceased, and the old lava flows have eroded into rich black soil (some of which washed down to the beach in Kawhia and stained our socks as we sank into the mud while digging for pipis). Mount Pirongia’s forested slopes offered early Maori settlers a variety of roots, berries, and birds to enrich their diet, and provided a place of refuge when hostile tribes attacked. For the Europeans who came to the Waikato region later, the Pirongia forest was a primary source of timber. Botanically, it forms a transition between the warmth-loving hardwood species of the north—kauri and rimu—and the beech forests of the south.

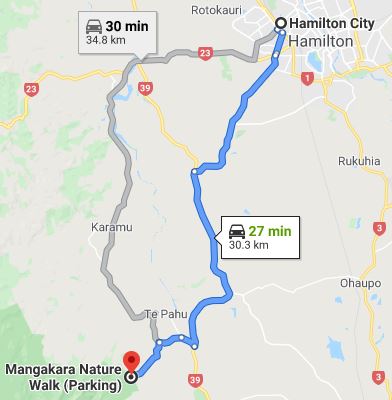

Today, the trees in the vast Pirongia Forest Park are protected from loggers, and the area has become a haven for hikers. There are over twenty hiking tracks, ranging from short loops for day-trippers to more demanding tramps up to each of the three summits. Huts with bunks, toilets, and cooking facilities are available for overnight trampers who want to do the whole circuit, but that wasn’t the experience we were seeking for our Monday excursion on 9 March. Instead, we chose the Mangakara Nature Walk, not necessarily because the Department of Conservation’s website lists it as “easy,” but because it’s short (less than 2 kilometers) and only 30 minutes from Hamilton. Having scheduled a video chat during the morning with our whanau (extended family—in this case, our children and grandchildren), we couldn’t leave until after lunch. Moreover, we weren’t sure how long the forecast rain would hold off, so a short, nearby walk was just what we needed. Elder and Sister G decided to accompany us.

The Mangakara Nature Walk follows the stream of the same name (Mangakara means dark water) through one of Pirongia’s patches of old-growth forest. As an interpretive walk, the track is posted with educational signs about the area’s flora and fauna. We heard rather than saw many birds, so we weren’t able to get photos of them; the plants, however, were more willing to sit still for our cameras.

The first three trees pictured below are examples of podocarps, an ancient family of evergreen hardwood conifers. Some resemble pines with a perfect Christmas-tree shape, but the leaves are short and less needlelike. Others don’t resemble pines at all. Podocarps produce fleshy cones that look like berries and must be similarly tasty because they are an important food source for birds—and, in the past, for humans.

Miro

The miro was valuable to the Maori because its fruit attracted kereru (wood pigeons), a favorite game bird. They also used gum from the bark as medicine for a variety of ailments, and oil from the fruit—which is edible even though it smells and tastes like turpentine—as an insect repellent. The wood is strong but has limited commercial applications because the mid-size trees tend to grow in distorted shapes.

Rimu

The rimu can live for hundreds of years and attain heights of 165 feet or more. Its beautiful golden-brown hardwood was once used by the Maori to make long spears, and now to make fine furniture. However, slow growth, overharvesting, and loss of habitat to farmland have severely reduced the number of rimu trees available to the timber industry. The reddish-black fruit was a good food source, while the drooping olive-green foliage, grayish-brown bark, and gum were used medicinally to stop bleeding and prevent scurvy.

Kahikatea

The kahikatea is the tallest of the podocarps, reaching nearly 200 feet in height. It has a distinctive gray, flaky bark, and its berry-like fruit was eaten by both birds and people.

Some early European explorers mistakenly thought that tall, straight kahikatea trunks would make excellent spars for their ships, and learned too late that the wood’s high sap content made it susceptible to borer insects and rot. However, the odorless and tasteless sap made the pliable wood ideal for food containers such as boxes for shipping butter and for baking cakes.

The next three trees are examples of broadleaf species.

Tawa

The tawa is one of the most common lowland trees of the North Island, often forming the canopy in mixed conifer–broadleaf forests. It can grow up to 100 feet tall and 4 feet in diameter. Its light-green leaves are similar to those of the willow, and although its flowers are small and inconspicuous, they develop into relatively large, dark red fruits, The tawa is dependent on the kereru and the endangered kokako to distribute its seeds because they’re the only birds big enough to swallow its fruit whole. Tawa trees produce a hard, resilient wood that is used for flooring, paneling, and dowels; the Maori used it for bird spears.

Pukatea

The pukatea, which can grow as tall as 115 feet, is recognizable by its flange-like, buttressing roots that absorb oxygen as well as providing support. The Maori treated toothaches and constipation with juices from pukatea bark, which contains a substance related to morphine but without the same side effects. However, caution is still in order because the bark and dried leaves have been known to poison rats and sheep. Pukatea wood is very light, making it useful for carving and for river canoes.

Kohekohe

The glossy, broad leaves of the kohekohe contain a chemical similar to quinine that traditionally has been used to treat sore throats, coughing, consumption, boils, and menstrual cramps. Its flowers, which grow directly out of the tree trunk, are a favorite food of red possums (an invasive marsupial from Australia that New Zealand hopes to eradicate). Kohekohe wood is reddish-brown, much like mahogany, and makes attractive furniture, but because the trunk tends to become hollow before it gets very big, these trees are rarely cultivated for timber.

Next come the ferns.

Silver fern

The silver fern, with its symmetrical arrangement of fronds, is found only in New Zealand, and has been accepted as a symbol of Kiwi national identity since the 1880s. According to a government website, “the elegant shape of the fronds stood for strength, stubborn resistance, and enduring power” in Maori lore. The leaves’ silvery white undersides reflect moonlight, making it easier for travelers to find their way through the bush at night.

Fork fern

The fluffy fork fern covering this tree trunk is an epiphyte, meaning that the plant uses its host for support, but doesn’t rob it of nutrients as does a parasite. Epiphytic plants are a common feature of New Zealand forests.

Northern rata

The reddish-brown roots descending the trunk of this tree belong to an epiphytic northern rata. This one likely began life as a wind-blown seed that landed in a fork of the tree and then sent its aerial roots down toward the soil. Eventually, the roots will form a “trunk” that encloses its host, while the leafy branches billow upward toward the light. Not all rata trees are epiphytic; they also can grow directly from the ground. Either way, they may reach 80 feet in height, with trunks 8 feet in diameter. A northern rata growing atop an already towering rimu is quite a sight, especially in the spring when its reddish puff-ball flowers are blooming.

Kareao

The black kareao vine was called “supplejack” by the crew of Captain Cook’s ship: supple because it bent in many directions, and jack because it was useful for many tasks. The Maori used it for ropes and woven baskets; it also has many medicinal applications, and young shoots reportedly taste like asparagus. A single vine can have up to fifty branches, effectively blocking human passage through parts of the forest.

Following the boardwalk through the forest

Crossing the Mangakara Stream

About 45 minutes into our learning expedition, it started to rain. Anticipating the chance of precipitation, we had come prepared with raincoats but picked up our pace anyway. Just as we got back to the shelter at the trailhead, someone in the sky suddenly began dumping buckets onto the Mangakara Nature Walk. Hoping the rain would let up soon, we decided to hang out in the shelter for a while before trying to cross the puddle-pocked carpark, but when it was still coming down just as hard twenty minutes later, we gave up, made a dash for the car, and drove home.

Sometime later, we had occasion to reflect on what we had learned about trees during our walk through the Pirongia Forest Park when Elder T shared the quote below during a morning devotional. It’s from Ram Dass, formerly known as Richard Alpert, a colleague of LSD-advocate Timothy Leary during the 1960s. Like many of his generation, Alpert turned to eastern religions, and was given the name Ram Dass (servant of God) by the Hindu mystic who became his guru. Now Ram Dass is himself a sort of guru, teaching people how to become more attuned to the spiritual in nature and in themselves.

When you go out into the woods, and you look at trees, you see all these different trees. And some of them are bent, and some of them are straight, and some of them are evergreens, and some of them are whatever. And you look at the tree and you allow it. You see why it is the way it is. You sort of understand that it didn’t get enough light, and so it turned that way. And you don’t get all emotional about it. You just allow it. You appreciate the tree.

The minute you get near humans, you lose all that. And you are constantly saying “You are too this,” or “I’m too this.” That judgment mind comes in. And so I practice turning people into trees. Which means appreciating them just the way they are.

We appreciated Elder T’s reminder that Jesus, too, counseled us to avoid “that judgment mind,” to seek to understand others and treat them with compassion and respect.

Here in New Zealand, we are learning to appreciate many new tree species, and to love many new human specimens, too.

I love this quote by Ram Dass, and learning about these trees from your experience. Thank you, and love you both❤️🤗