Thursday 6 February was Waitangi Day, a national holiday commemorating the signing of a treaty between the British Crown and the Maori that is considered New Zealand’s founding document. The treaty, signed at Waitangi in 1840, provided a path for New Zealand to become a unified nation-state under the protection of the Crown, but by some it is seen as a document that the Pakeha colonists used to con the Maori out of their land. That faction regards Waitangi Day in the same way many Native Americans regard Columbus Day: not only unworthy of celebration, but downright offensive. Most Kiwis, however, observe Waitangi Day with mild patriotism, but mostly with gratitude for a day off work.

Thursday 6 February was Waitangi Day, a national holiday commemorating the signing of a treaty between the British Crown and the Maori that is considered New Zealand’s founding document. The treaty, signed at Waitangi in 1840, provided a path for New Zealand to become a unified nation-state under the protection of the Crown, but by some it is seen as a document that the Pakeha colonists used to con the Maori out of their land. That faction regards Waitangi Day in the same way many Native Americans regard Columbus Day: not only unworthy of celebration, but downright offensive. Most Kiwis, however, observe Waitangi Day with mild patriotism, but mostly with gratitude for a day off work.

Because the MCPCHC would be closed along with all other public venues for the holiday, Barry suggested that the seven full-time missionaries who work there take a trip to Tauranga, and arranged to borrow the mission van so all of us could ride together. Barry chose Tauranga not because it has any historic significance connected with Waitangi Day, but because it has historic significance for the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints in New Zealand.

Tauranga is located about 80 kilometres from Hamilton on the Bay of Plenty, which is on the Pacific (east) coast of the North Island. It’s both a major shipping port and a popular beach resort, and because the harbor offers wide, deep berths, it’s also a favorite port-of-call for big cruise ships.

Entrance to Gate Pa

But we weren’t visiting as typical tourists. Our first stop, Gate Pa, actually did have some patriotic significance because an important battle took place there in 1864, after the locus of New Zealand’s Land Wars moved from Waikato to Tauranga. A pa generally refers to a fortified settlement; this one was named for the gated bridge that crosses a ditch along one of its boundaries.

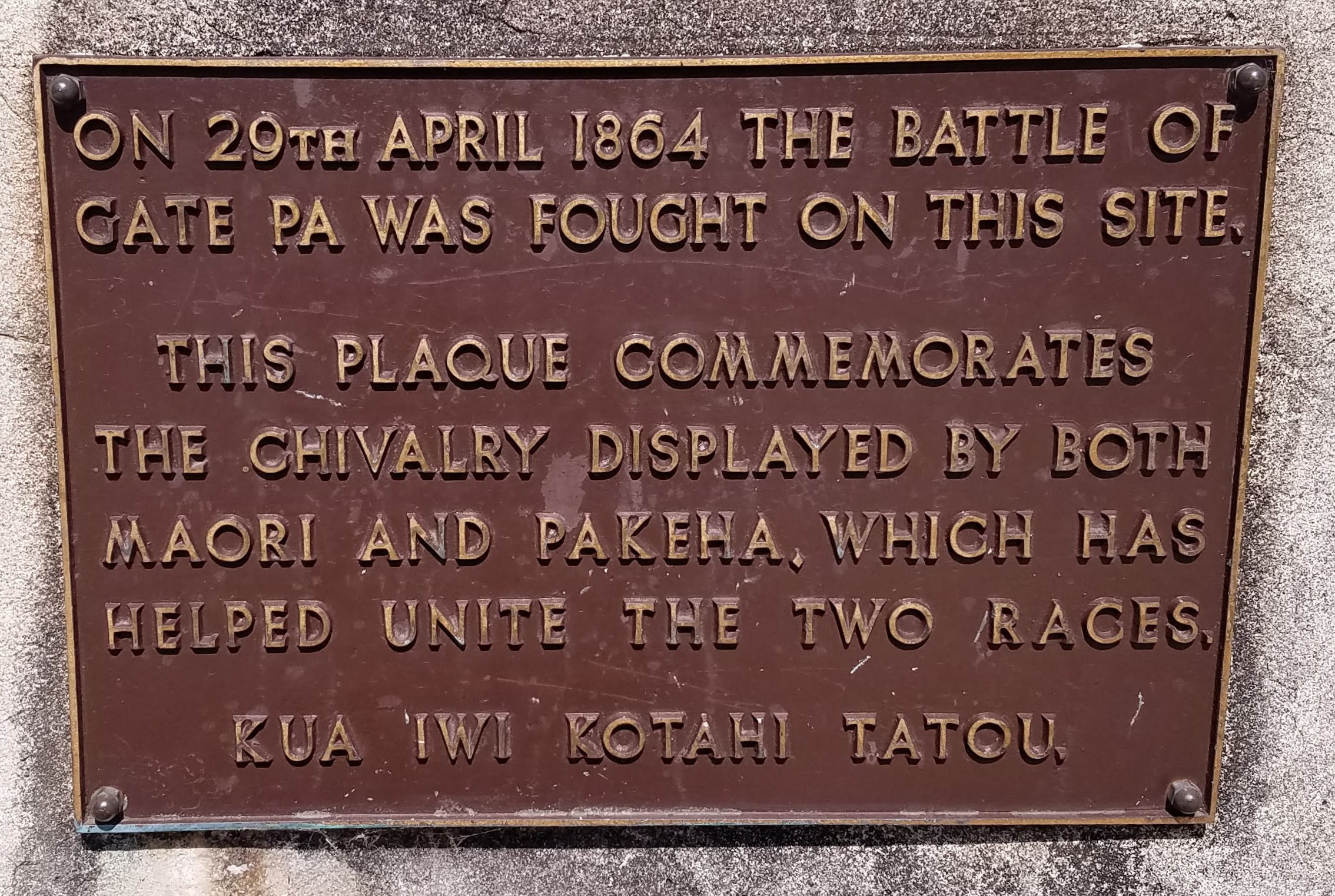

Plaque commemorating the battle

On 29 April 1864, both a British army regiment and a naval brigade pummeled Gate Pa from two sides with big guns for eight hours and then, seeing no signs of life and thinking they had annihilated the Maori defenders, the British enthusiastically moved in to take the pa. To their great surprise, they were met by “very sharp fire” that immediately took down dozens of men. What the British hadn’t realized was that the Maori had hidden themselves in a series of trenches, similar to the foxholes later employed in World War I, and hadn’t been hit by the gunfire at all. Although the defenders were far outnumbered by the attackers, the latter suffered more than twice as many casualties during the assault, including most of their officers. Without commanding leadership the assault forces scattered in disarray, leaving their dead and wounded behind. It is telling that after the British retreated, the Maori tended not only to their own fallen warriors, but also offered water and kindness to their wounded enemies.

Monument to Matthew Cowley

This is the kind of attitude and behavior that endeared the Maori to Matthew Cowley (discussed at length in another post). Our next stop was at the Matiu Kauri Grove (that’s Matthew Cowley spelled as the Maori pronounce his name), where a monument in his honor was erected in 2017.

The grove of trees where the young LDS missionary had spent so much time praying for help while he studied the Maori language had been preserved as a community park for many years.

Matiu Kauri (Matthew Cowley) Grove. Kia ngawari was Elder Cowley’s motto: “Be humble, be loving, be gentle, be kind”

As the centennial of Matthew Cowley’s arrival in New Zealand approached in 2014, the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints proposed that Churchill Park (named only for the road on which it is located) be renamed in honor of the missionary who had devoted so much of his life to sharing the gospel of Christ in New Zealand. Finding little opposition to the Church’s proposal and considerable support from the community, the Tauranga City Council agreed to the name change and the placement of a historical marker. The grove is not very big, but it’s a peaceful place that affords a glimpse of the Bay of Plenty. Perhaps a few of its tall kauri trees were there at the same time as Matiu Kauri himself.

Our cohort: Diane (Sister E), Michael, Nancy, Barry & Eva (Elder & Sister G), Wendy & Alan (Sister & Elder T)

Soon after we arrived at the Grove, we were met by Thomas and Janette Tata, Tauranga residents with deep ties to both The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints and the local Maori community’s Huria (Judea) Marae, which was next on our itinerary for the day.

Huria Marae

A marae is a community gathering place, centered around a whare (or wharenui, if it’s a large one), a sacred house of worship and learning. A marae is a place of turangawaewae (literally, footprints), where one can plant his or her feet and be recognized as part of the community. It may belong to an iwi (tribe), a hapu (sub-tribe) or a whanau (extended family). The Huria Marae belongs to Ngai Tamarawaho, a hapu within the Tauranga Moana iwi. Many of its people accepted the restored gospel when missionaries from The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints began teaching the Maori there in the early twentieth century.

Thomas and Janette Tata

Thomas is a kaumatua (elder) of the marae, and a renowned manu korero (orator) of Ngai Tamarawaho. He’s also an elder of the Church, and a respected professor of Maori culture at the University of Waikato. Barry had arranged for the Tatas to meet us that morning so that Thomas could take us inside Huria Marae’s wharenui and share with us the stories of his people, which are depicted symbolically within it.

Because most of our group had not previously visited this marae, we had to be ceremonially welcomed with a powhiri before entering the wharenui. In this ritual, a female elder from the host community—in our case, Janette—issues the karanga, a keening call representing a rope that pulls visitors safely into the wharenui, as if they were arriving in a waka (canoe). Once inside, the host men speak words of welcome and offer a prayer, each followed by a traditional waiata (song) sung by the host women. The visitors then respond with a song (fortunately, it did not have to be in Maori, and we could choose whatever song we liked; Sister T suggested that we sing “I Am a Child of God,” a simple hymn that Latter-day Saints learn as children). Finally, each member of the host group greets each member of the visitor group with a nose-to-nose hongi. (In New Zealand, you don’t rub noses, but simply press them together.) Thomas pointed out that a powhiri demonstrates the complementarity of the roles of men and women in Maori culture; both are necessary to the well-being of the community, and one does not hold or exercise more authority than the other.

Carvings and woven tukutuku alternate along the walls of the wharenui

In a similar way, the interior of the wharenui also represents the way men and women work together to support the community. The walls consist of floor-to-ceiling wood carvings, alternating with tukutuku (panels of woven fibers). The wooden sculptures, created by men, portray the purakao (legends) of the Ngai Tamarawaho; the tukutuku, woven by women, trace the hapu’s whakapapa (genealogy) back to the ancestors whose waka arrived on the shore of the Bay of Plenty hundreds of years ago. Thanks to a strong tradition of oral history and tukutuku such as these, nearly every Maori can trace his or her lineage back to a specific waka that landed somewhere on the coast of New Zealand in the thirteenth century. The history, legends, and genealogies of a community are passed from generation to generation during youth instruction sessions held in the wharenui—perhaps the equivalent of Catholic catechism classes. As a university professor as well as an elder of his hapu, Thomas has made a career of passing on such information, but all adults share responsibility for making the marae a space where the community’s young people can “plant their feet” and belong.

Tama-te-kapua with his stilts

Thomas didn’t attempt to interpret every symbolic artwork inside the wharenui for us, but selected only a few of the wood carvings illustrating the legends of his people. Pointing to a figure with a human head and torso on long, thin, stick-like legs, he explained that this was Tama-te-kapua, the mischievous captain of Te Arawa waka, whose people settled in Rotorua. According to legend, young Tama-te-kapua raided his neighbor’s garden while using stilts so that he would leave no footprints to betray his identity. Later, when he was about to lead a band of his compatriots away from their Hawaiki homeland in search of other shores, he persuaded the chief high priest of his iwi to come aboard Te Awara with his two wives to pronounce a blessing on the waka. Before the priest and his wives could disembark, Tama-te-kapua shoved off, thus assuring that the new settlement he hoped to establish across the sea would have a high priest.

Apanui with his tui

Another story Thomas shared involved a descendant of Tama-te-kapua named Apanui. Because of his noble ancestry, at a very young age Apanui was given a large tract of land between the Motu River and the Bay of Plenty, along with the responsibility to defend its inhabitants. Apanui felt unprepared for such a charge, and was reluctant to take the lead. He allowed others to go in front when his hapu was attacked by marauders. As a result, he not only lost battles, but lost the confidence of his people. Desperate to change his situation, he traveled to a neighboring territory to seek advice from Kinomoirua, its old, wise chief.

Kinomoirua was expecting him because a tui bird had seen Apanui and his attendants from afar and told the chief that visitors were coming. He received them warmly, and then asked Apanui why he had come.

“I don’t know what to do,” Apanui cried. “I am losing all my battles. Why is this happening? What must I do to change my luck?”

Kinomoirua did not answer, nor did he offer any advice. Instead, he asked the young man to follow him to the shore at the foot of Maunganui, the mountain that overlooks Tauranga. “Sit with me here, and watch that rock,” said Kinomoirua, pointing to a stone mound rising from the water a little way off. There they remained in silence for the next several hours. Gradually, the tide came in, totally submerging the rock. The old chief did not rise, and did not speak for several more hours. Eventually, the tide went out again, and the rock appeared once more.

At last the old man turned to Apanui and spoke. “What does it mean?” he asked.

Apanui replied, “It means that I must be seen in front of my people all the time. I cannot hide, because they need to know I am there.”

Kinomoirua was pleased; the young man had learned his lesson. Kinomoira gave Apanui the tui bird that had announced his arrival, and in time he gave Apanui his daughter as a wife, thus cementing the bond between their two hapu.

After keeping us spellbound with stories for about an hour, Thomas seemed to be bringing his presentation to a close, but Nancy was curious about something he had not yet addressed. “What about the ceiling?” she asked. “What do the painted designs represent?”

Inside the wharenui

Thomas smiled and asked, “What do you think? What is above us all?”

“The sky. The heavens,” we responded.

“Exactly,” said Thomas. “The designs represent gifts from above that connect heaven and earth: the clouds that bring rain, the sun that provides warmth, the air that gives life to all.”

WWI Memorial

Outside the wharenui is a memorial to the Maori soldiers from Tauranga who fought in World War I. Matthew Cowley had blessed them that, like birds, they would return home. Although most came back severely wounded, all of them did return.

Eating our lunch in a park on Tauranga Harbour

It was already past lunchtime when we left the marae, so Thomas suggested that we stop at a bakery, which in New Zealand is less a bakery than a fast-food takeaway where you can buy ready-made sandwiches, meat pies, single-serving quiches, and sometimes salads in addition to muffins, scones, and biscuits (what we would call cookies). Michael chose a chicken kebab, while Nancy decided to try a chicken and vegetable pot pie. (The crust was surprisingly flaky, considering that it probably had been sitting in the display case most of the morning.) We took our purchases away, of course, driving to a park on the water where we had a beautiful view of Maunganui and Tauranga Harbor on the far side of the bay.

Maunganui, seen from across Tauranga Harbour. (Note the monstrous cruise ship on the right)

Before we headed toward the harbor, we made a brief visit to the Otumoetai Pa Historic Reserve. Otumoetai Pa was the largest settlement in the region from 1600 to 1865, with a peak population of about two thousand. It was the site of some major battles of the Musket Wars, conflicts that took place among the Maori iwi during the early 1800s, before the British established domination. It’s also the site of an important peace treaty that brought those tribal wars to an end. After the rangatira (chief) of the pa rejected the Waitangi Treaty, the colonial government confiscated the land in 1864 and the Maori were forced to leave their ancestral home.

Otumoetai Pa Historic Reserve

The acreage that is now the historic reserve was acquired by the Matheson family, who built a homestead and developed a prosperous farm there. During the early twentieth century, Fairview Farm became the social center of the area as the Mathesons hosted many picnics for the Waikato Hunt Club and held dances in their large living room, but eventually the farm declined and pieces of the property were sold off. In 2004, when the heirs of the Matheson family realized the historical importance of their land to the local Maori, they sold the remaining parcel to the City of Tauranga, requesting that the farm buildings be demolished and the area turned into a historic reserve and archaeological site.

From the Otumoetai Reserve, we drove through Tauranga’s sprawling harbor toward the beaches—along with what seemed to be everyone else in New Zealand. (Remember, it was a national holiday, a fine sunny day, and Tauranga is a resort town.) Adding to the foot traffic as we neared the beaches were thousands of tourists who had been disgorged from a gargantuan cruise ship moored in the harbor. This part of Tauranga is on a long, narrow peninsula—less than four blocks wide at some points—with beaches that face the ocean on one side and the harbor on the other. After we managed to find a place to park the van, we walked the rest of the way down the road that ended at the oceanside beach, but that was not our destination. Instead of turning right toward the sand, as most people were doing, we turned left, following a trail that leads toward Maunganui, an extinct volcano that rises dramatically from the tip of the peninsula.

Welcome to Mauao

Maunganui is known by most Kiwis as “The Mount.” The name is not terribly descriptive because Maunganui simply means “big mountain” in Maori; the Maori themselves call it Mauao, a much more picturesque name that means “caught by the light of day.” In the associated legend, Mauao was at first an unnamed, nondescript inland hill that was desperately in love with a lushly forested mountain named Puwhenau. But Puwhenau was the lover of Otaneiwainuku, the great mountain that reigned over the whole area. With no hope of winning Puwhenau’s love, the despondent hill implored the putupaiarehe (forest fairies) to drag him to the ocean so he could drown himself. The putupaiarehe complied with his request (gouging out the Waimapu River valley as they pulled him along), but just as they reached the ocean, the sun began to rise. Afraid to be caught away from their forest haven in full daylight, the fairies fled, leaving the poor hill stranded at the tip of the peninsula, “caught by the light of day”—but now he at least had a name.

On his point overlooking the ocean, Mauao also acquired a new purpose. Archaeological digs on and around The Mount have uncovered at least three pa (villages) that had existed for centuries. The most strategic was on the summit, which affords a commanding view of the Bay of Plenty and the volcanic plateau that extends inland toward Rotorua. The base on the south side, however, was more hospitable, providing inhabitants with fertile soil and natural freshwater springs. Mauao/Maunganui was confiscated by the British in 1865, under the terms of the Waitangi Treaty, and soon a Pakeha settlement grew up around it. It’s now one of Tauranga’s most prosperous business districts, but The Mount itself has been preserved as a natural recreation area, popular with hikers and hang gliders. In 2008, ownership of Mauao was officially returned to the Maori tribes who still consider it a sacred place.

Pointed rock in the Bay of Plenty

Looking north toward Coromandel Peninsula

We followed the 3.4 kilometer track that circumnavigates the base of The Mount until Thomas stopped and directed us to take a seat in the shade of a gnarled tree, overlooking the scoop of Pacific Ocean that forms the Bay of Plenty. Once we had settled ourselves in the long grass next to the trail, Thomas pointed to a large rock rising from the water about a hundred yards out. “See that pointed rock?” he asked. “That is the one Apanui and Kinomoirua watched as the tide came in and out, hundreds of years ago. We are sitting where they sat as Apanui, the ancestor of my people, learned his lesson.”

Enjoying the little shade we could find: Thomas, Alan, Wendy, Janette, Nancy, Diane, Eva, and Barry

Thomas shared a few more stories as we watched the water ripple toward the shore, but the sun was shooing away our shade and we decided that we’d best move on. The afternoon had become hot enough to discourage us from hiking any farther around Maunganui on the now shadeless track, so we began retracing our steps back toward the main beach.

Alan’s collection of shells

On the way, Alan left the path and clambered down the embankment so he could pick up some nice seashells from the thousands piled up among the rocks on the shore. Wendy—also a shell collector—decided to follow him down the hill. The rest of us watched in horror as she slipped halfway down, bracing her fall with the hand whose broken bones had only recently healed enough to come out of a brace. Although she tried to pretend that her new injury wasn’t too bad, we could tell that Sister T was in a lot of pain, so we hurried back to the van, thanked the Tatas for an unforgettable afternoon, and headed toward Hamilton as speedily as possible. We were grateful that the van had a good air conditioner.

Public bicycle tool kiosk in the Mount Manganui district

Before we left Tauranga, we made a quick stop at a convenience store to get some ice for Wendy’s swelling hand. When we arrived in Hamilton two hours later, we drove directly to an urgent care facility and dropped her off so that she could have her hand x-rayed and reset if necessary. Alan continued to the MCPCHC with us to get the car they had left there earlier, and then returned to the care facility to pick Wendy up. The next morning, Sister T came to work with a new brace; this time she had broken her wrist.

Despite the day’s unhappy ending, our trip to Tauranga had been one of our most enjoyable and memorable thus far. Nancy would like to share a particularly significant moment she experienced as those of us being welcomed to the Huria Marae sang “I Am a Child of God” during the powhiri.

I am a child of God

And He has sent me here,

Has given me an earthly home,

With parents kind and dear.

Lead me, guide me, walk beside me,

Help me find the way.

Teach me all that I must do

To live with Him someday.— Naomi W. Randall, 1957

Nancy says:

I have sung this song thousands of times since early childhood, and I’ve always appreciated its reminder that we are indeed the offspring of a Heavenly Father (and a Heavenly Mother) who sent us to earth so we can learn and progress. But when I stood in the wharenui at the Huria Marae on Waitangi Day and began to sing it again as part of the powhiri, the second line suddenly took on a completely new meaning for me. “He has sent me here” no longer meant only that Father has sent me to earth, but also that he has sent me to New Zealand. I was struck by a powerful spiritual assurance that God knows me, that he loves me, and that this is where he wants me to be. I do not yet know exactly why he has sent me here, but I am certain that it is for a good reason, and I am grateful.

Great korero. I am so pleased you enjoyed your time with Tamati (Thomas) and at our marae and maunga (Mauao). Nga mihi – Buddy Mikaere