Navigating the hallway was more difficult with passenger luggage in the way

Last night we had been instructed to put our luggage in the hall outside our doors by 6:00 a.m. Not wanting to wear the same clothes two days in a row, we got up early enough to shower and dress before saying good-bye to our bags. As it turned out, we could have slept a lot longer, because when we left the room at 8:00 a.m. to go upstairs for breakfast, we found our bags still waiting in the passage—although, along with everyone else’s, they had been moved closer to the ship’s gangway entrance/exit, which also is on Level 4.

The needle of the barometer in our room had moved counterclockwise during the night, so we kept our raincoats with us

While waiting for the breakfast buffet to open, we took advantage of the early dawn to watch our approach into Copenhagen’s harbor, where dozens of wind turbines rise out of the sea. We learned later that the inclined roof of the harbor’s power generating plant serves double-duty as a ski slope!

Power generating plant, complete with ski slope

Wind turbines in the harbor

Langelinie terminal

The Star Breeze docked in the Langelinie terminal. We disembarked around 9:15 as part of the “green group”: passengers who had arranged their own onshore transportation. Carol and Jim had made the arrangements for our group, so a bus, driver, and guide were waiting for us as soon as we walked off the ship.

The Little Mermaid

The Langelinie pier is also the site of Copenhagen’s most famous statue, so visiting the Little Mermaid was our first stop. No one can say exactly why this surprisingly small bronze became such a popular and iconic symbol of Copenhagen. It was created by sculptor Edvard Eriksen in 1909 on a commission from Carl Jacobsen, founder of the Carlsberg Brewery, who had been impressed by a ballet based on Hans Christian Andersen’s tale. Jacobsen asked the artist to use the dancer who had portrayed the Little Mermaid in the ballet as his model; Eriksen complied with regard to the face, but used his own wife as the model for the figure.

Jens, our Danish guide

The mermaid is never named in Andersen’s story, and her fate is not as happy as is Ariel’s in the Disney version: the prince never realizes that it is the mermaid who saved him from drowning, so he marries someone else. The mermaid dies heartbroken, but because she refuses to harm the prince or his wife when given the chance, she becomes a “daughter of the air” rather than dissolving into seafoam. Nancy had grown up with a replica of Eriksen’s statue in her home, a gift from a family friend who had served a mission in Denmark, so she was eager to see the original. Unfortunately, so were a lot of other people. Having to compete for a satisfactory view with visitors from the six other cruise ships docked at Langelinie meant that our “short stop for a quick photo” took more than an hour.

Mastekranen

As we drove to our next stop, Jens, our guide, pointed out the Mastekranen across the harbor in Holmen, former home of the Royal Naval Shipyards. This is a large wooden crane that was used to place the masts on newly constructed ships during the eighteenth century, now preserved as a historic monument.

Holmen also is the home of the submarine Denmark deployed to the Gulf War, HDMS (Her Danish Majesty’s Ship) Sælen, now maintained by the Royal Naval Museum.

Sælen

On our way into central Copenhagen, Jens informed us that today is Denmark’s Flag Day (yet another national holiday!). Danes have good reason to celebrate today in particular: according to legend, the Dannebrog (Danish flag) descended from heaven while Valdemar was conquering the Estonian stronghold on Toompea Hill on 15 June 1219, exactly eight hundred years ago. Even if its true origin was not quite so miraculous, the Dannebrog can still claim to be the world’s oldest national flag in continuous use.

Happy 800th birthday to the Dannebrog!

Denmark was one of Europe’s great political and economic powers during the Middle Ages, controlling much of the land surrounding the Baltic and Norwegian Seas. However, its strength and influence began to wane in the seventeenth century. In 1659, after a stinging defeat by the forces of Karl X Gustav, Denmark lost all territory in what is now Sweden. In 1814, after choosing the wrong allies in the Napoleonic wars, it lost Norway. In 1864, as a result of the Schleswig Wars (the first of which Nancy’s great-grandfather participated in), Denmark was forced to cede more land to Prussia. And in 1944, when the Nazis invaded Denmark, Iceland cut the last remaining ties with its former ruler. Currently, the Kingdom of Denmark occupies only the peninsula that divides the Baltic from the North Sea, and a cluster of nearby islands; it also includes Greenland and the Faroe Islands (which lie halfway between Norway and Iceland), but both of those distant territories are self-governing.

Christian IX’s Palace, residence of Queen Margrethe II. Notice the split pennant (and the chimneys)

Our next stop was Amalienborg, a complex of four nearly identical palaces that have served as residences for the royal family since 1794. Built in the mid-eighteenth century during the reign of Frederik V, the palaces were originally intended for four different noble families, but were taken over by the royals after their home, Christiansborg Palace, was severely damaged by fire. Jens pointed out that Denmark’s current monarch, 79-year-old Queen Margrethe II, must be in residence here today because the royal family’s distinctive split-pennant-style Danneborg is flying from the flagstaff of her palace. He also told us that we could distinguish the queen’s palace from the other three because it has the most chimneys—appropriate, he joked, because Margrethe is a chain smoker.

Frederick VIII Palace, residence of Crown Prince Frederik and family

Another royal Danneborg waves over Crown Prince Frederik’s palace, which he shares with his wife Mary and their four children. Frederick, age 51, is popular with his people; he served in the Royal Navy’s elite special operations corps (the Frogmen), and was the first royal of any nation to become an Ironman.

Danish Royal Family. Prince Henrik, the queen’s consort, died in 2018

Queen Margrethe’s younger son, Prince Joachim, and his family live elsewhere. Denmark became a constitutional monarchy in 1848, so the queen has few official duties other than to appoint a prime minister and preside over state ceremonies. In 1953, an Act of Succession declared that a female could inherit the throne if the deceased monarch had no sons; in 2009, that act was amended to stipulate that regardless of gender, the first-born child would be the heir.

Frederik V

In the center of Amalienborg’s octagonal plaza is a monumental statue of Frederik V, which portrays him as if he were a Roman emperor (all the rage for eighteenth-century monarchs). According to Jens, the sculpture took fourteen years to complete (1753-68) because the workers were paid by the hour and thus had reason to take their time.

Frederik’s Church. The inscription: “The word of the Lord endures forever”

The project consumed so much of the royal budget that Frederik’s Church, under construction during the same period about 300 meters away, had to be abandoned, and was not completed until 1894. The rococco-style building is popularly known as Marmorkirken (Marble Church), despite the fact that it was constructed largely of limestone instead of marble to save money.

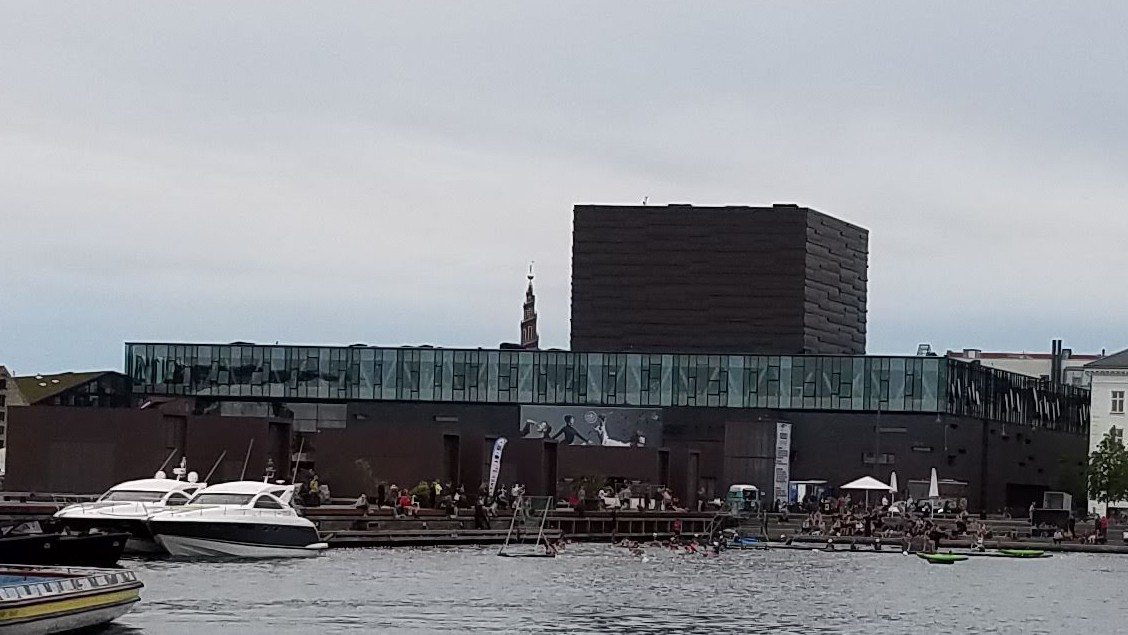

Copenhagen Opera House

When we were through taking photos, Jens led us from Amalienborg’s plaza toward a waterfront park just outside the palace complex. Across the harbor to the east is the contemporary Copenhagen Opera House, which opened in 2005.

Royal Danish Playhouse

Looking south from the park we could see the equally modern Royal Danish Playhouse, which opened in 2008. Nearly half the cantilevered building extends over the water, and its parking garage is actually under the water. We were intrigued to learn that the playhouse, which includes three theatres, not only presents plays, but also hosts diving competitions from its rooftop platform. Other community events are held in an adjacent public plaza.

Nyhavn

Around the corner from the Playhouse is Nyhavn (Newport), Copenhagen’s thriving entertainment district. The brightly painted cafés, restaurants, and shops lining the man-made canal were once seedy taverns and bordellos, but today the carousing sailors they catered to have been replaced by tourists.

We were grateful that Jens had led us to better toilet facilities than this dank cavern

… although the flush buttons in the other public toilet looked disturbingly like security cameras

At the end of the canal is King’s New Square. In 1670, King Christian V replaced a muddy marketplace with cobblestones and tidy gardens—and of course, commissioned a monumental statue of himself on a horse, wearing the garb of (you guessed it) a Roman emperor. The square is surrounded by the old Royal Danish Theatre, the Academy of Fine Arts, and other gracious buildings from past centuries.

King’s New Square; Christian V; Royal Danish Theatre

Børsen (Old Stock Exchange)

A short bus ride from King’s New Square is one of the oldest buildings in Copenhagen, the Børsen (Old Stock Exchange), built in 1625. When we hear “stock exchange,” we tend to think of frantic traders in shirtsleeves, loosened ties askew, shouting orders at each other amid heaps of unspooled ticker tape. However, when Copenhagen’s Stock Exchange was in active use the cacophony within was more likely produced by cattle and sheep, because this was a livestock exchange, a busy marketplace next to the pier where trading ships unloaded their cargo. The Børsen’s unique steeple features the intertwined tails of four dragons, topped by three crowns that represent the three realms of the Scandinavian empire (Denmark, Norway, and Sweden). Unlike the flying serpents that torch buildings in The Story of Owen, the Dragon Slayer of Trondheim, the dragons atop the Børsen are said to have protected the Old Stock Exchange from fire. Indeed, even though several nearby structures have burned down since 1625, the Børsen has been spared any such damage. These days the historic building is closed to the public, used exclusively for what Jens described as “chichi exhibits and wine tastings.”

The Danes love their bicycles and leave them safely in a parking lot near the train station

Christiansborg Palace

Across the street is a large government complex whose centerpiece is Christiansborg Palace, the royal residence abandoned for Amalienborg in 1794 when the former went up in flames. Generations of Danish bishops and monarchs had occupied a succession of castles and palaces on this site since 1167. Another palace built here during the nineteenth century became the home of the Danish Parliament after the establishment of the constitutional monarchy in 1849, but that structure also was destroyed by fire. The current incarnation of Christiansborg Palace, completed in 1928, has the distinction of being the only building in the world that is occupied by all three branches of its country’s government: the Regeringen (Cabinet), presided over by the Prime Minister, comprises the executive branch; the Folketinget (legislature), whose 179 representatives face elections every four years; and the Højesteret (Supreme Court), whose members are nominated by the executive branch but are formally appointed by the king or queen.

Frederik VII

The large equestrian statue in the plaza in front of the palace represents Frederik VII, the king who reigned as absolute monarch for only a year and a half before bowing to public pressure and granting his country the right to be ruled by a constitutional government. Since taking this action in 1849, Frederik VII has been regarded as a national hero, and the inscription on the statue’s pedestal reads: “The people’s love is my strength.” Denmark has since become a socialist society, with taxes consuming more than half of workers’ income, but Jens says that the Danes do not resent those taxes because of the abundant services the national government provides.

Royal Stables

Behind Christiansborg Palace are the Royal Stables, the only part of the eighteenth-century complex that survived the last two major fires. The buildings are still used to house horses and carriages that transport the royals for ceremonial occasions.

Royal Library Gardens

Beyond the stables is the former site of the Royal Naval Shipyard, but its arsenal and supply depot have been replaced by a peaceful garden and the Royal Library, which was built in 1906.

Søren Kierkegaard contemplates life outside the Royal Library

The 8-meter copper sculpture in the garden of the Royal Library was designed by Mogens Møller as “a monument to the written word.” It shoots a column of water into the air every hour on the hour

The library’s collection includes a Gutenberg bible, and the papers of both Hans Christian Andersen and Søren Kierkegaard, one of the most influential philosophers of the nineteenth century. (Kierkegaard was the main subject of Michael’s master’s thesis, as well as one of the two people for whom our oldest son is named, the other being Nancy’s great-grandfather.)

Holocaust memorial at the Jewish Museum

At the southern end of the gardens is the Danish Jewish Museum, which occupies a building that was once the Royal Boat House. Although a group of stone blocks outside the museum memorializes the millions of Jews who lost their lives in the Holocaust, the focus inside is on the cultural heritage of Danish Jews. Danes are justly proud of the fact that during the Nazi occupation in the 1940s, the Danish Resistance spirited 7,220 Jews out of Denmark and into Sweden to avoid the arrest and deportation Hitler had ordered. Later, the Danes arranged liberation for 464 of their Jewish compatriots who had been sent to a concentration camp in Czechoslovakia. Astoundingly, 99 percent of Denmark’s Jewish community thus managed to survive the Holocaust. During the Middle Ages, Jews were prohibited from even entering Denmark, but that changed in the seventeenth century when Danish kings sought to increase the country’s income through commerce with wealthy Jewish merchants. Today, Jews represent only a tiny sliver of the Danish population (six thousand in a country of six million), and most have become as secularized as everyone else, but it was gratifying to see that their unique heritage is being preserved and celebrated in a prominent public space.

The Black Diamond

On the opposite side of the Jewish Museum and the red brick Royal Library is a huge, modern library annex known as the Black Diamond. The whole complex, holding 34 million items, constitutes both the National Library of Denmark and the library of the University of Copenhagen, and is the largest library system in Scandinavia.

Our salad sampler: beet, shaved celery, and bulgur with chicken and mango

Danish open-face sandwiches

It had started to rain by the time we got back on the bus and headed toward Torvehallerne, a bustling urban market with stalls purveying all sorts of food, drink, and fresh produce. The market would have been the perfect lunch stop had it not been so crowded with locals and tourists trying to both eat and stay out of the rain, but even so it was fun to push through the aisles and look at so many tantalizing food choices.

Passing up both a traditional Danish open-face sandwich and the chance to try some fresh but uncooked seafood, we opted instead for a three-salad sampler and a couple of pastries.

We acknowledged polite requests to leave certain tables for customers of a particular vendor, but didn’t heed them because there were so few places that weren’t dripping wet

Rosenborg Castle

After lunch, we went up the street to visit Rosenborg Castle, where King Christian IV lived for most of his adult life. Christian IV became king at age 11 and ruled for nearly sixty years (1588-1648), the longest reign of any monarch in Scandinavia. Jens told us that Christian IV’s reign was nearly cut short when his son-in-law got drunk one night and fell into the moat. The similarly inebriated king jumped in to rescue him and almost drowned, but both managed to survive.

Changing of the Guard

Like the Børsen and many other historic buildings in Denmark, Rosenborg Castle is built in the style of the Dutch Renaissance, which is characterized by stepped gables, highly ornamented façades, and striking contrasts between red brick and gray stone. Its most notable feature is the treasury where the crown jewels and other royal regalia are on display, but we didn’t take time to go inside to see them.

Rosenborg Gardens

Instead, we watched the changing of the guard and strolled around the garden (the oldest royal garden in Denmark), where a family of ducks and a big grey heron were enjoying the drizzly weather.

Vor Frue Kirke

At the final stop of today’s sightseeing tour, Vor Frue Kirke (Church of Our Lady), what our guide expected to be a fairly short, routine visit became a transcendent experience for all of us.

A church in one form or another has existed on the site of Vor Frue Kirke since 1127. For centuries it was administered by Roman Catholics and called St. Mary’s, but after the Reformation the king forced the Catholic clergy to share the building with Protestant priests. That uncomfortable situation did not last long. In 1530, angry Lutherans stormed the church and destroyed everything that offended their puritanical sensibilities: richly decorated altars, statuary, vestments, reliquaries, chalices, and censers. Even the building’s name had to go. The title “Saint” in reference to Mary was eschewed by the Lutherans, so the church became known simply as the Church of Our Lady. Shortly thereafter, it became the seat of the presiding bishops of the Evangelical Lutheran Church in Denmark, although it was not designated as the national cathedral until 1924.

Vor Frue Kirke interior

Architecturally, the church has gone through many incarnations. The gothic-style building that existed when it was taken over by the Lutherans was destroyed by fires resulting from a series of lightning strikes, and the red brick structure that replaced it was leveled in 1807 when the British Navy bombarded Copenhagen during the Napoleonic Wars. The current neoclassical cathedral was completed in 1829.

So what made our visit today so unforgettable?

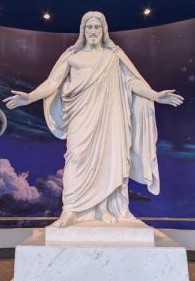

A copy of Thorvaldsen’s Christus at the Salt Lake City Visitors’ Center

Whether we realize it or not, all members of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints have a connection to the Church of Our Lady in Copenhagen because it is the home of the original Christus statue by Bertel Thorvaldsen. A copy of this marble representation of the resurrected Christ dominates the dramatic rotunda of the Visitors’ Center on Temple Square in Salt Lake City, and additional copies in all sizes can be found in other Latter-day Saint buildings and homes around the globe, making it one of the most recognizable artworks for Mormons everywhere.

The inscription on the base of the Christus reads: “Come unto me” (Matthew 11:28); the superscription says: “This is my beloved son, hear him” (Luke 9:35)

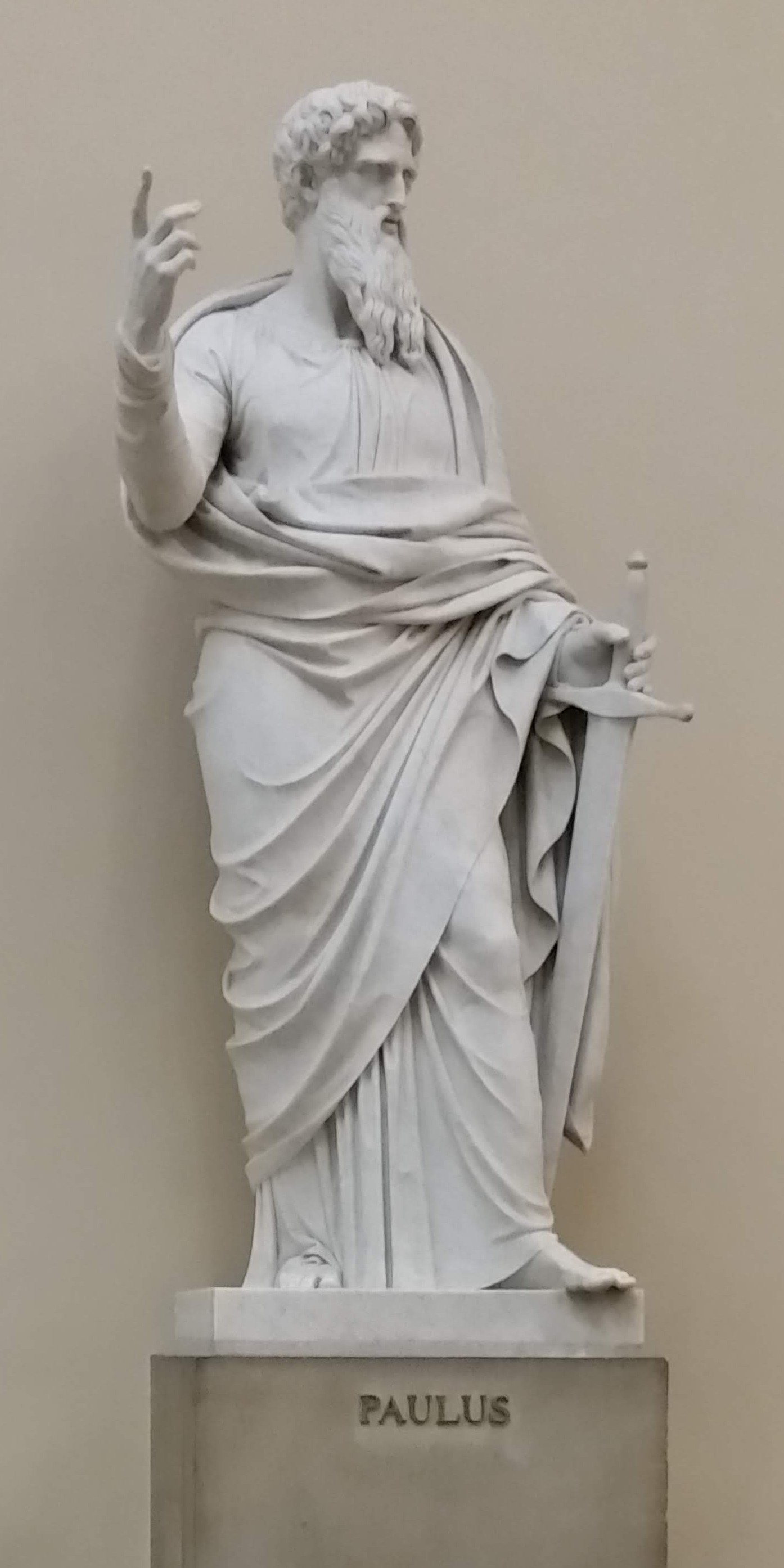

When Vor Frue Kirke was rebuilt in the 1820s, sculptor Thorvaldsen was commissioned to create not only a statue of Christ, but also statues of the Twelve Apostles to adorn the interior. The project took twenty years to complete, and the artworks were finally installed in 1848. In 1950, Elder Steven L. Richards, an apostle of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, visited the Church of Our Lady in Copenhagen and was deeply impressed by Thorvaldsen’s sculptures, which he described as “awe-inspiring.” Several years later, after seeking the appropriate permissions, Elder Richards succeeded in having an exact duplicate of the Christus installed in the Church’s Visitors’ Center on Temple Square as an unmistakable indication that Mormons not only believe in Jesus Christ, but that he is central to our doctrine and essential to our salvation.

Thorvaldsen chose to replace Judas Iscariot with St. Paul in his portrayal of the Twelve Apostles

Members of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints do not venerate statues, crucifixes, icons, or other depictions of deity, so our houses of worship typically are not decorated with such items; we don’t even display any simple crosses. Thorvaldsen’s Christus is a notable exception, and because the sculpture is so pervasive in our culture, visiting Vor Frue Kirke in Copenhagen to see the original has become almost the Mormon equivalent of a pilgrimage. So here we were, twenty-two Latter-day Saint tourists, reverently approaching the outstretched arms of the marble statue as if the Savior himself were standing on the pedestal.

“This is the most Catholic I’ve ever seen all y’all!” exclaimed Mary-Anne, the former New England parochial school student, using the parlance she had picked up during her years in Nashville. We laughed, but she had a point. It was indeed an awe-inspiring experience to gaze at the faces of Christ and his apostles and contemplate their enormous impact on the world and on our individual lives.

Jens was intrigued by our unusual interest. “Most of the groups I bring in here take a quick look around and then are ready to move on after ten or fifteen minutes,” he said, “but you guys can’t seem to get enough of being here. I’m not a religious person, but as I watch you look at these statues, I am profoundly moved. It’s an honor to be able to share this experience with you.”

Hotel Kong Arthur

Our compact room . . .

. . . and compact bathroom

When our “pilgrimage” was over, we reboarded the bus for the short drive to our lodgings, and then said goodbye and thank you to Jens for a memorable tour. As we checked into the Hotel Kong Arthur, the receptionist cheerily informed us that this is a “green” establishment, which we soon understood to mean that there is no air conditioning.

Our tiny room on the fourth floor of the rear wing was suffocating, so we immediately opened the window to let in some cool early-evening air. The rain had ended and shafts of sunlight filled the room as they pierced through still-lowering clouds.

Tomorrow morning, some of our group will be heading to the airport for their flight home; by Monday morning, most of the others will have departed, too. A few die-hards (Pam, Eric, Lynn, Mark, Nancy, and Michael) wanted to add a few more days to our stay in Denmark, so we are not leaving until Tuesday. But tonight would be the last time our Montgomery, Ohio-based group would be together, and we wanted to make the evening special. Michael had thus made arrangements for a celebration dinner at Cofoco, a restaurant that he had found recommended online.

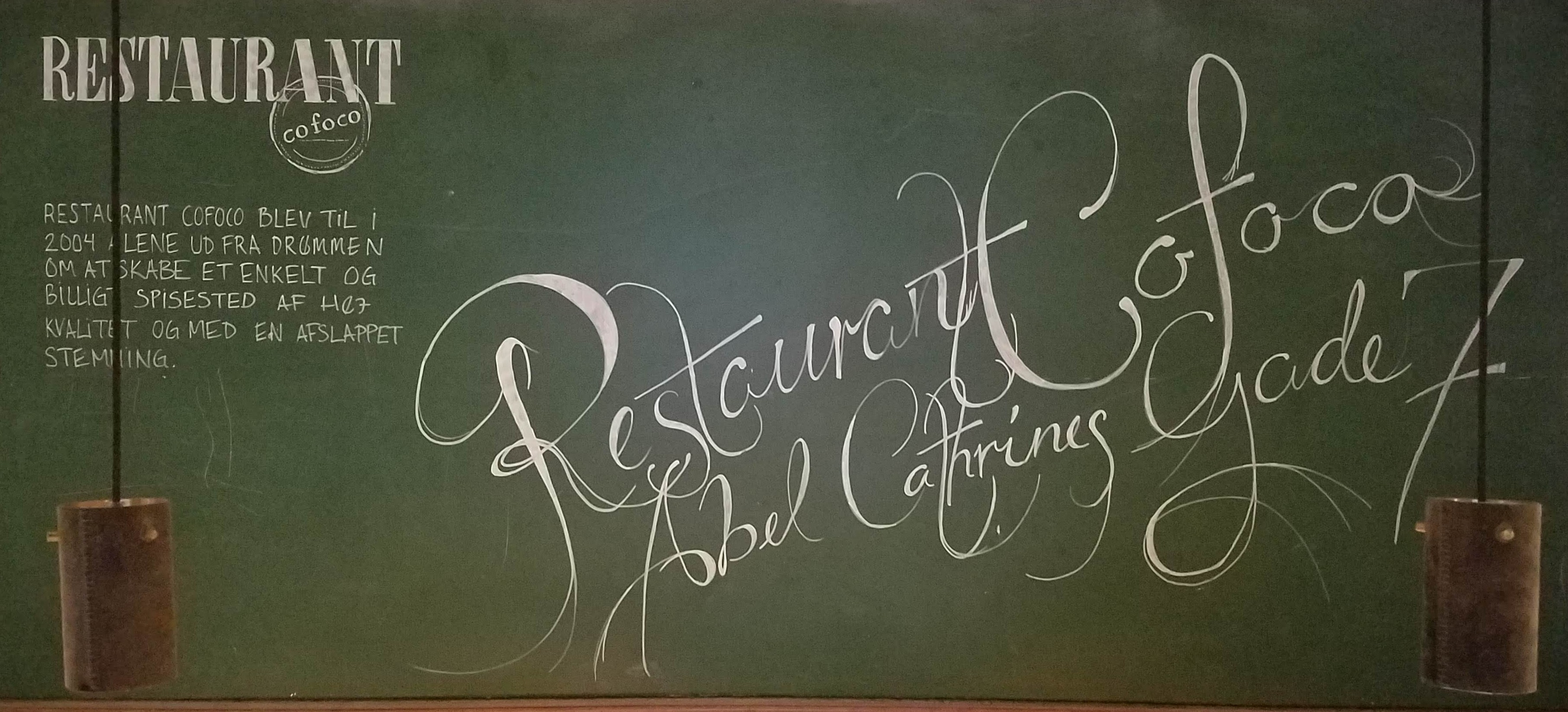

According to its website, Cofoco is an acronym for Copenhagen Food Collective, a group of restaurants that focus on “supporting a sustainable future” by serving locally sourced food and participating in other green initiatives, such as operating on power from their own solar park and charging diners an extra 9 kroner (about $1.35) per meal to plant a fruit tree. The website describes the menu and decor of Cofoco’s flagship restaurant as “full of contrasts: the rustic and the elegant, the simple and the complex. We start with great Danish ingredients and prepare them in the way they shine brightest.” Michael thought this sounded good, so after consulting with the other prospective diners from our group as well as the restaurant staff, he reserved a table for eighteen and ordered the six-course, fixed-price menu for all of us. We were anticipating a meal of traditional Danish foods prepared and presented with contemporary flair, and we were not disappointed.

Welcome to Cofoco

But first we had to get to the restaurant. The Hotel Kong Arthur is located half a block from Søgade, a busy boulevard that parallels the eastern shore of Copenhagen’s Søerne (The Lakes). Cofoco is in the Vesterbro district at the south end of The Lakes, about 2 kilometers away from the hotel. Michael decided that the distance was walkable, so he asked everyone to meet in the hotel lobby at 5:30 p.m. A few couples didn’t make it on time, but Michael took off anyway, setting a brisk pace so that at least some of us would arrive at the restaurant by 6:00, when we were expected. Our group thus formed a loose parade strung out along Søgade, with those at the tail end trying to maintain visual contact with those ahead of them because no one but Michael knew exactly where we were going.

Group shot at Restaurant Cofoco

Eventually everyone made it, and we were seated at a long table along one wall of the “rustic but elegant” restaurant. After learning that none of us would be drinking wine tonight, our servers suggested that we try the beetroot lemonade, which was refreshingly piquant.

Bread and butter

The servers also brought several small loaves of crusty, multigrain bread accompanied by slabs of fresh butter. These were consumed so quickly that we almost missed the opportunity to get a photo.

As the plates for the first course began to arrive, and at each succeeding course, the hostess came to our table and explained what we were about to eat.

Tuna tartare

1st: Tuna tartare with ponzu and miso mayonnaise, garnished with crispy puffed wild rice, green asparagus shavings, and nasturtium blossoms

Lynn looked at her plate skeptically, sighed, and took a bit of raw tuna on her fork. Ten minutes later, everything on her plate was gone. Turning to Michael she said, “Thank you for doing this, because Mark and I have eaten something we never would have ordered ourselves, and it was delicious!”

Soup

2nd: Mussel broth with green peas and smoked haddock, topped with croutons and droplets of mint oil

Katie shuddered. “Peas,” she moaned. “I hate peas. I’ve always hated peas. They’re squishy and mealy, but then they’ve got those skins that get stuck in your teeth—just a bad combination of textures. And smoked haddock? Really?” Gamely, she dipped her spoon in. And then, like Lynn, she happily drained the bowl.

White asparagus

3rd: White asparagus with foamy smoked goat cheese, trout roe, mustard seeds, and cress

Some of us were reluctant to try the trout roe, but decided that the little golden pearls were quite tasty. Katie finished the course and then exclaimed, “I’ve just eaten three things I can’t stand, and I loved them!”

Flat Iron Steak

4th: Flat iron steak on new potatoes with parsley, cabbage, chickweed, and salted lemon sauce

Cheese

5th: Gammelknas cheese with rhubarb compote and rye bread (a scrumptious take on the European cheese-fruit course)

Sorbet

6th: Verbena sorbet on a bed of vanilla crumble, sliced strawberries, and mounds of herbal white chocolate, all surrounded by a moat of yuzu-flavored buttermilk

No one voiced any complaints through the last three courses.

Toasting enduring friendships with beetroot lemonade

Before the meal ended, Tony was inspired to propose a toast “to friends we will always remember.” This was a playful response to a discussion we had had during the meal (between ecstatic “Mmms” over the food) about how difficult it can be to maintain relationships with friends who move far away. We are grateful for this particular group of people who have remained dear friends despite the geographical distances between us. Tony’s sentiment was one to which all of us were happy to raise a glass.

Siciliansk Is

7th: Michael ordered chocolate, mango, and rhubarb; Nancy had rhubarb, blueberry, and elderflower

One would think that after such a meal, we’d all be entirely satisfied. However, Nancy had read in a guidebook to Denmark that the best gelato in Copenhagen was to be had at a place called Siciliansk Is, which happened to be only three blocks away from Restaurant Cofoco. The proximity presented a temptation too great to resist. Some of the group could justify adding a second dessert course to tonight’s feast because they are flying home in the morning and won’t have another opportunity to try Copenhagen’s best gelato. Those of us who aren’t leaving Copenhagen for a few more days wanted the chance to decide for ourselves whether the guidebook’s assessment was correct, so off to Siciliansk Is we went. We have not yet sampled gelato anywhere else in Copenhagen so it’s too soon to reach a verdict—but we look forward to gathering more evidence.

Michael allowed us a more leisurely pace as we walked back toward the hotel. On the return trip, we discovered that we should have crossed Søgade and taken the footpath through the narrow greenspace along the shore of The Lakes—a much more picturesque route than the east side of the busy boulevard.

Lingering on the Queen Louise Bridge

With plenty of daylight left before bedtime, several of us lingered on the Queen Louise Bridge just north of the hotel, watching swans in the water and cyclists on the street glide by.

Courtyard outside our window

When we returned to our room, we found it unbearably hot. Moving a small electric fan from the wall unit to a shelf by the window didn’t help much, especially in the bathroom, where the temperature was stifling. We soon discovered the reason for that: the towel warmer was on (why??) and emitting a tremendous amount of heat. None of the wall switches in the room would turn it off, but after a long search we finally found a small switch hidden on the back of the warmer itself. Even after the source of the heat had been eliminated, the temperature of the room remained high. How would we be able to sleep? We stripped the duvet and top sheet from the bed, positioned the fan so that it would blow directly on us, stripped off our clothes, and then lay down, hoping for the best.

Now, remember, it’s still light outside, and likely to remain so throughout the night. We can’t use the pull-down window shade because if we do, it will block our only source of cool air. The blackout curtain does not reach across the entire window, leaving a ten-inch gap that Michael has tried to fill with pillows. He understands that the pillows will hinder the passage of cool air, but he also knows that any scrap of light will keep him awake. A slight breeze from the open window is making the blackout curtain billow at irregular intervals, and each billow allows a burst of light to escape into the room. Michael finds this intolerable, so he keeps getting out of bed to try to adjust the curtain, the pillows, the fan, and the window into some arrangement that will allow him to go to sleep. After about an hour of being disturbed by Michael’s unsuccessful efforts to control his environment, Nancy said, “Look, you can either have it light and cool or dark and hot; there are no other options. So decide on one and then get back into bed and stay there.”

He chose light and cool. Somehow, both of us managed to fall asleep.

Leave A Comment