After our wonderful dinner last night, we knew that Marty would not disappoint us at breakfast—and he did not. We woke to a delightful breakfast spread of yogurt, butter rolls, muesli, pineapple, avocados, cucumbers, and sundried tomatoes. The highlight, however, was the rhubarb juice, not just because it was unusual for these Americans, but because it was really good.

Aerial view of Gendarmenmarkt

Deutcher Dom (on a sunnier day than today)

Französischer Dom

Konzerthaus Berlin in Gendarmenmarkt. The statue in the center of the square honors poet and philosopher Friedrich Schiller

After breakfast, we bundled up in our rain gear and headed out. Our plan for the morning was to attend a rehearsal of the Staatsoperchor (State Opera Chorus) so we could watch Marty at work. To get to the rehearsal venue, we took a bus and then walked across the Gendarmenmarkt. The marketplace established here in 1688 quickly acquired the name Gens d’Armes because the regiment’s stables were located in the vicinity. The current platz was created in 1773, after the stables were moved elsewhere. Apparently the marketplace has moved elsewhere, too, because we saw no vendors at all, although we hear that the Gendarmenmarkt bustles with booths at Christmastime. Two huge churches flank the square: the Französischer Dom (French Cathedral), built by the Huguenots about 1705, and the very similar Deutcher Dom (German Cathedral), built by the Lutherans a few years later. Eventually the Evangelical Church of Prussia (and then Germany) took over both buildings. The French Dom is still used as a place of Protestant worship, but the German Dom now houses the Bundestag’s exhibition on German parliamentary history. The third imposing building on the Gendarmenmarkt is the Konzerthaus Berlin, home of yet another major orchestra. The concert hall was built on the ruins of the National Theater, which burned down in the early nineteenth century. Every structure on the platz suffered heavy damage during World War II, so all had to be reconstructed during the latter half of the twentieth century.

The square next to the opera house, prepared for “Staatsoper für alle”

Continuing to walk northeast from the Gendarmenmarkt, and after passing a couple of blocks of nondescript office buildings, we found ourselves at the south end of the platz adjacent to the Staatsoper Unter den Linden. (Unter den Linden is the name of the grand boulevard that runs through central Berlin from the Alexanderplatz to the Brandenburg Gate.) This week, the square is surrounded by temporary fencing set up to contain the crowd expected to participate in “Staatsoper für alle”: that is, watching tonight’s opera on a jumbotron, in the open air. Dodging rain puddles as we hurried across the windswept platz, we considered the plight of those unfortunate opera-lovers who had been unable to reserve seats for tonight’s performance and would be left out in the cold– especially because those unfortunate, ticketless opera-lovers included us!

The jumbotron and sound tower set up to live-stream the opera for ticketless guests

When we decided to embark on this journey to Berlin for the grand reopening of the Staatsoper, Marty had warned us that he would not be able to provide tickets for opening night, nor for any performance this week. “They’re being very strict,” he said. “No comp tickets at all, unless you’re an official dignitary.” So Michael had set his alarm for 4:00 am on the day in August when Staatsoper tickets were supposed to go on sale online, only to find that not a single ticket was available. Apparently, subscription holders had exercised their priority advantage and snatched up every seat, so Michael purchased tickets for the Vienna Philharmonic concert to be held at the Staatsoper tomorrow night, and we resigned ourselves to watching the opera en plein air.

We asked Marty why Robert Schumann’s Szenen aus Goethes Faust (Scenes from Goethe’s Faust) had been chosen to celebrate the Staatsoper’s reopening because it’s a relatively obscure work, and not even a true opera. He explained that an original opera had been commissioned for the occasion, but the building renovation was only supposed to take three years, and when it became apparent that the Staatsoper would not be ready to reopen in 2013 as expected, the commissioned composer decided to give the work to the Deutsche Oper (the crosstown rival) instead. As the Staatsoper’s renovation progressed, a second opera was commissioned; however, the composer became ill and was unable to continue working. When it appeared that the hall would be ready to open in late 2017 and the second commissioned piece was nowhere near finished, the directors decided that they’d better prepare something else. Unity Day–3 October, celebrating Germany’s reunification in 1990–was chosen for the Staatsoper’s grand re-opening. Marty told us that by the time that date was announced, it was too late to sign any big-name soloists, so Barenboim et al decided on the Schumann because it could be performed by the Staatsoper’s resident ensemble. Besides, it seemed appropriate: What could be more thoroughly German than Robert Schumann’s philosophical musings on Goethe’s Faust?

Interior of the renovated Staatsoper

The Staatsoper’s pink exterior makes it a standout among its staid gray neighbors

Unfortunately, the Staatsoper’s renovation still is not entirely done. The whole building had been gutted to repair groundwater damage to the foundation. Some Berliners had hoped that the hall–last rebuilt after the ravages of World War II in a style that critics fondly call “socialist faux rococo”–would be completely redesigned, but traditionalists prevailed. Marty told us that the ceiling had been raised five meters because Barenboim had requested changes to improve the acoustics, but otherwise the building looks much like it might have when it first opened in 1743. The entrance appears ready to receive visitors, but construction equipment and materials still clutter the rear. The plan is to present a few gala performances this week, then reclose the building until work is completed in December.

The Staatsoper’s administrative building. Artistic Director Daniel Barenboim’s office is behind the grand windows above the entrance

This morning we walked on past the opera house, heading instead for a building in the next block that houses the Staatsoper’s administrative offices. This structure has been renovated, too, mostly to accommodate expanded rehearsal space and an underground tunnel connecting it to the performance hall. Like’s Daniel Barenboim’s, Marty’s office is in the old part of building, but unlike Barenboim’s it does not appear calculated to impress visitors. On the other hand, the new chorus rehearsal room is first-rate, with tiered seating and good acoustics. Marty pointed out chairs near the side of the room where we could sit, and while he talked with the accompanist at the grand piano, we took the opportunity to look at the posters and photos of past productions lining the walls.

As we watched chorus members arrive, take off their coats, and settle into their seats, it was kind of weird to realize that all these people were just coming to work; they are state employees, and singing in the opera chorus is their full-time job. One of the first things we noticed about them was their diversity: ages appear to range from mid-twenties to mid-sixties, and their ethnic mix comprises northern Europeans, Mediterraneans, and Asians–but no black Africans. A few, including the rehearsal pianist, are American–as is the director, of course.

The Staatsoperchor prepares to rehearse. Marty is at the podium

Yesterday Michael had asked Marty, “How’s your German?” and Marty had replied, “Well, I’ve learned enough to get by.” But as the chorus master took his place behind the substantial podium and called for everyone’s attention, we were impressed by his confidence and his fluency. Marty has always had a knack for languages, and after three years here, German seems to flow naturally from him, especially in the context of music. In the context of music, we could kind of follow what he was telling the singers. Michael had the advantage of having taken a few years of German in high school, but Nancy was forced to rely mostly on nonverbal cues and picking out the occasional English cognate. Meanwhile, no one in the chorus questioned Marty’s instructions regarding pronunciation and articulation, despite the fact that most of them are native German speakers and he is not. As he reviewed the notes he had taken during Wednesday night’s performance of the Schumann (the one attended by the likes of Chancellor Angela Merkel and the mayor) and then rehearsed some troublesome sections that had not met his standards, it was obvious that everyone respected Marty’s professionalism and mastery of his art. We were a little awed ourselves.

Marty had told us that in addition to Szenen aus Goethes Faust, the Staatsoper is preparing to perform the German Requiem by Johannes Brahms, and that during today’s rehearsal we would be welcome to sit among the chorus and sing along if we wanted to. The three of us had sung the Brahms Requiem with the Oratorio Choir during our freshman year at BYU, so we were looking forward to revisiting that music together after the chorus’s lunch break. However, as Marty announced break time, the singers reminded him that since there would be a performance tonight, they should have the afternoon off.

“Ah! Na sicher! Bis heute Abend!” (“Of course! Until this evening, then!”) he said, waving as the chorus members donned their coats and walked out. It was another reminder that these are state employees, protected by union rules that limit the number of hours they work each day. The Staatsoper performs virtually year-round, several nights a week, mounting four or five different operas at a time in repertory. The schedule is grueling, so the singers are understandably protective of their afternoons off. For many of them, it’s their only time to spend with family.

Stylized linden leaves decorate doors, windows, and walls all over the Staatsoper’s administration and rehearsal building

The Staatsoper has existed since 1742, in the days of Frederick the Great. Originally the Hofoper (Court Opera), the organization’s name has changed periodically along with the party in power, but it has always been one of Europe’s finest companies. When Berlin was divided after World War II, the Staatsoper Unter den Linden ended up on the east side of the wall and thus came under the purview of the Communists. Still supported by the government (as are Berlin’s other two major opera companies), the Staatsoper has a tremendous advantage over most arts organizations in the U.S.: its directors do not have to worry about fundraising. This is why Daniel Barenboim (and probably Martin Wright) plans to stay at the Staatsoper until the baton drops from his cold, dead hand. Other Staatsoper performers and staff enjoy a similar advantage: they are tenured employees who cannot be fired. This situation sometimes poses a challenge for the directors, however. What do you do with an aging tenor who must remain onboard even though he can no longer sail through the high Cs? The company has had to become creative in its solutions. According to the chorus master, the opera’s library department is way overstaffed with former singers. Dancers who develop arthritis might become stagehands. Marty’s secretary was once a fine soprano, but when she reached the point when she could no longer control her vocal vibrato, she was gently removed from the chorus. Marty says he would have preferred to have a secretary with better writing and keyboarding skills, but the woman had not yet reached retirement age, and it was less risky to put her to work behind a desk than to keep her onstage.

During the morning, Marty had introduced us to the chorus and to a few of his colleagues (but not to Daniel Barenboim, alas), mentioning that although we had come to Berlin specifically for the opera, we would be watching it from the platz outside because we had been unable to get tickets. After the rehearsal, someone told him that they had heard a few tickets for tonight’s performance had been returned to the box office, so we made a beeline there immediately, hoping that at least two seats were still available. Our disappointment at not being able to sing along with the Brahms this afternoon was more than assuaged when we were able to obtain tickets for seats in the lower rang (balcony). We paid a hefty price for them, but now we could look forward to watching the show without getting drenched.

Lunch at the casino

Happy and now hungry, we returned to the admin building and headed for the “casino,” which is not a gaming venue but rather the employee cafeteria and lounge. Menu choices were limited and traditionally German: our plates were filled with substantial slabs of braised beef covered in brown gravy, boiled potatoes, and rotkohl (red cabbage). The meat was overcooked and under-seasoned, but the spicy cabbage balanced it out. While the meal certainly was not as good as what Marty has been feeding us, it was convenient and satisfying, and seemed entirely appropriate to the circumstances.

Humboldt University

Rank and file chorus members may have had the afternoon off today but Marty didn’t, so we left him “at the office” and took off to see more of Berlin on our own. The rain had let up but it was still pretty cold, so we decided to take a bus up to the Brandenburg Gate at the west end of Unter den Linden. The transit stop immediately across the street from the Staatsoper also serves Humboldt University. Sometimes called the “mother of all modern universities,” the school pioneered a holistic educational model that integrates studies in the arts and sciences. Alumni include Karl Marx, Max Planck, Otto von Bismark, and W. E. B. du Bois. During the DDR period, the institution moved to West Berlin to avoid Communist repression and was renamed the Free University. Since 1990, the university has regained its original name and location along with its global prestige.

Construction for a new subway line along Unter den Linden forced the removal of most of the boulevard’s namesake linden trees; we saw these along the nearby Ebertstrasse, and imagined how beautiful Berlin’s tree-lined major avenues must look in warmer seasons

The Brandenburg Gate is probably Berlin’s most recognizable landmark. Originally one of eighteen gates in the wall that surrounded the city during the seventeenth century, it has been the scene of some of Berlin’s most significant events. Napoleon celebrated his 1806 victory over the Prussian army by marching through this gate, and then by carrying the Quadriga sculpture from its top off to Paris with him. (The bronze horse-drawn chariot was returned to its proper place after Napoleon’s defeat in 1814.)

Brandenburg Gate

Nancy with Minerva, goddess of wisdom, under the Brandenburg Gate

The Brandenburg Gate became a symbol of the Nazi party during its rise to power in the 1930s, and although it was damaged during World War II, it was one of the few structures in the neighborhood to remain standing. When the Berlin Wall went up in 1961, the Brandenburg Gate was completely closed to traffic. In 1989, when the DDR finally collapsed, Chancellor Helmut Kohl walked through the gate to symbolize Germany’s reunification.

Initial view of the Holocaust Memorial

Variation in depth starts to make it more interesting

From the Brandenburg Gate, we walked south along Ebertstrasse toward the Holocaust Memorial, or more formally, the Memorial to the Murdered Jews of Europe–a rather lurid name for what is actually a rather understated monument. Completed in 2006, the memorial consists of 2711 concrete slabs, each about the length and width of a coffin, laid out in a grid about the size of a large city block. The top surfaces of all the slabs are set at about the same altitude, so from the perimeter the memorial looks like a uniform set of benches. However, as we began to walk among them, the ground under our feet unexpectedly sloped, and we soon found ourselves plunged into a maze of towering pillars. Ground level continued to undulate as we wandered, so that while we could easily look over the tops of the gray slabs from one vantage point, a few more steps might take us back into a shadowy concrete forest. We never encountered any dead ends, just lots of possible paths to explore and ponder.

From the depths of the memorial for a very different perspective

We aren’t sure exactly what message designer Peter Eisenman intended to convey–nor what the significance of the number 2711 is–but as we were drawn deeper into the monument physically, we also felt drawn deeper emotionally. Casual passersby may pause for a moment and feel dismayed by what looks like thousands of graves, just as those who read about the Holocaust may be horrified by the actual death count. But this memorial moves those who enter to truly contemplate light and darkness, good and evil, and the incalculable loss of six million lives.

Bundesrat

Walking east along Leipzigerstrasse, the next big boulevard south of the memorial, we passed the home of the Bundesrat, the upper chamber of Germany’s federal government. From what we have gathered, the Bundesrat is sort of a cross between the U.S. Senate and the British House of Lords in that representation is based on political entities (i.e. states) but the members are not elected–at least not by the populace. Instead, members are elected from each of the sixteen states by local officials, who naturally vote along party lines.

Floral sculpture in the atrium of the Mall of Berlin

Across from the Bundesrat building is proof that since reunification, East Berlin has become fully invested in the capitalist economy: the glass-enclosed, multilevel Mall of Berlin looked no different and was just as busy as any urban mall we’ve visited in the U.S.

Entering the American sector

Turning south onto Friedrichstrasse, we knew we had reached what used to be known as “the American Sector” of the formerly partitioned city when we encountered McDonald’s, KFC, and Starbucks. What we were looking for, however, was Checkpoint Charlie, the famous and most heavily used passage through the Wall that once separated West Berlin from East. Today, the grim, DMZ-like swath of no-man’s-land that existed here during the Cold War years has vanished under a jumble of modern office buildings.

Checkpoint Charlie

Only Checkpoint Charlie’s guardhouse remains, occupied by unsmiling, uniformed actors with no authority to stop traffic or ask for anyone’s papers. Traffic tends to slow down there anyway because the guardhouse stands in the middle of the street, surrounded by hordes of photo-snapping tourists (ourselves among them).

Remnants of the wall

On a nearby corner lot is a simple memorial with a few sections of the Wall on display–a ready-made photo-op in a more convenient location. Also on the lot is a small building containing old photos and descriptions of the neighborhood during its days of infamy. The larger Mauermuseum am Checkpoint Charlie (Wall Museum at Checkpoint Charlie) is just down the street, but we decided to skip it and head back to Marty’s apartment so we could do some laundry and rest before our big night at the opera. (What a relief to know that we wouldn’t have to spend it shivering in front of the jumbotron!)

Waiting for the U-Bahn

For whatever reason, tonight’s performance of Szenen aus Goethes Faust was scheduled to begin at 6:00 p.m.–18:00 on most local clocks, and early by any standard. Although we weren’t very hungry after our meat-and-potatoes lunch at the Staatsoper casino, we knew we wouldn’t have another chance to eat before the opera was over, so we heated up the leftover Thai soup from last night and cut into a fresh loaf of bread just before donning concert attire and heading to the U-bahn station. Berlin’s public transportation system is convenient and easy to navigate, so even though Marty wasn’t there to guide us this time, we had no trouble finding our way back to the opera house.

Entering the renovated Staatsoper

A literal red carpet welcomed us into the Staatsoper. As we checked our coats, Nancy looked around to make sure that what she had chosen to wear tonight was OK. A couple of months ago, she had sent an earnest message to a music-loving female friend who has lived in Germany for several years: “What does one wear to the opera in Berlin? I know what to wear to the opera in Cincinnati, and I know what to wear to the opera in Los Angeles, Chicago, New York, Paris, and Madrid, but Berlin? And during the re-opening gala? I don’t want to commit a faux pas, especially since we’ll be the chorus master’s guests and probably won’t be sitting in the cheap seats.” (This was back when we thought we’d be able to buy tickets online–but now that we actually held tickets to some not-cheap seats, the question had become applicable again.)

The red carpet welcomes a visitor in monochromatic black

Melissa had replied: “Dark, monochromatic colors, preferably black. Definitely nothing flashy. Berlin fashion is very understated.” So now Nancy looked around–and silently chuckled. Nearly every woman in the house was wearing monochromatic black. She felt that the navy blue of her own gown provided just the right scintilla of distinction. (Later, she spotted a middle-aged couple who clearly had not read the memo: she was wearing a bright red dress, he a matching scarlet jacket over a shirt printed with images of women’s faces that were large enough to be recognizable at forty paces. The combination of his costume and his handlebar moustache made Nancy wonder whether the man was trying to channel his inner Mephistopheles.)

Welcoming Hall of the Staatsoper

While most of the newly refurbished interior of the Staatsoper looked marvelous–still rococo, but less over-the-top than it might have been–we could see evidence that the renovation is not yet complete. Marty had told us that much of the work still to be done involves behind-the-scenes technical equipment, but one bit of unfinished business that was immediately obvious to audience members was the number of not-yet-functioning toilets. One would think that completing the restrooms by opening night should have been on the high-priority list, but apparently it wasn’t.

View from our seats in the first balcony

Our seats were in the third row of the first balcony, just to the right of the center section, with a clear view of the stage. Since we had neglected to research Scenes from Goethe’s Faust before we arrived and the program notes were, of course, in German, we had little idea of what to expect in terms of the opera’s narrative. Both of us had been assigned to read excerpts from Goethe’s Faust as Humanities majors at BYU and thus we knew the basic outline of the classic story of a man who sells his soul to the devil, but details from those long-ago readings escaped us.

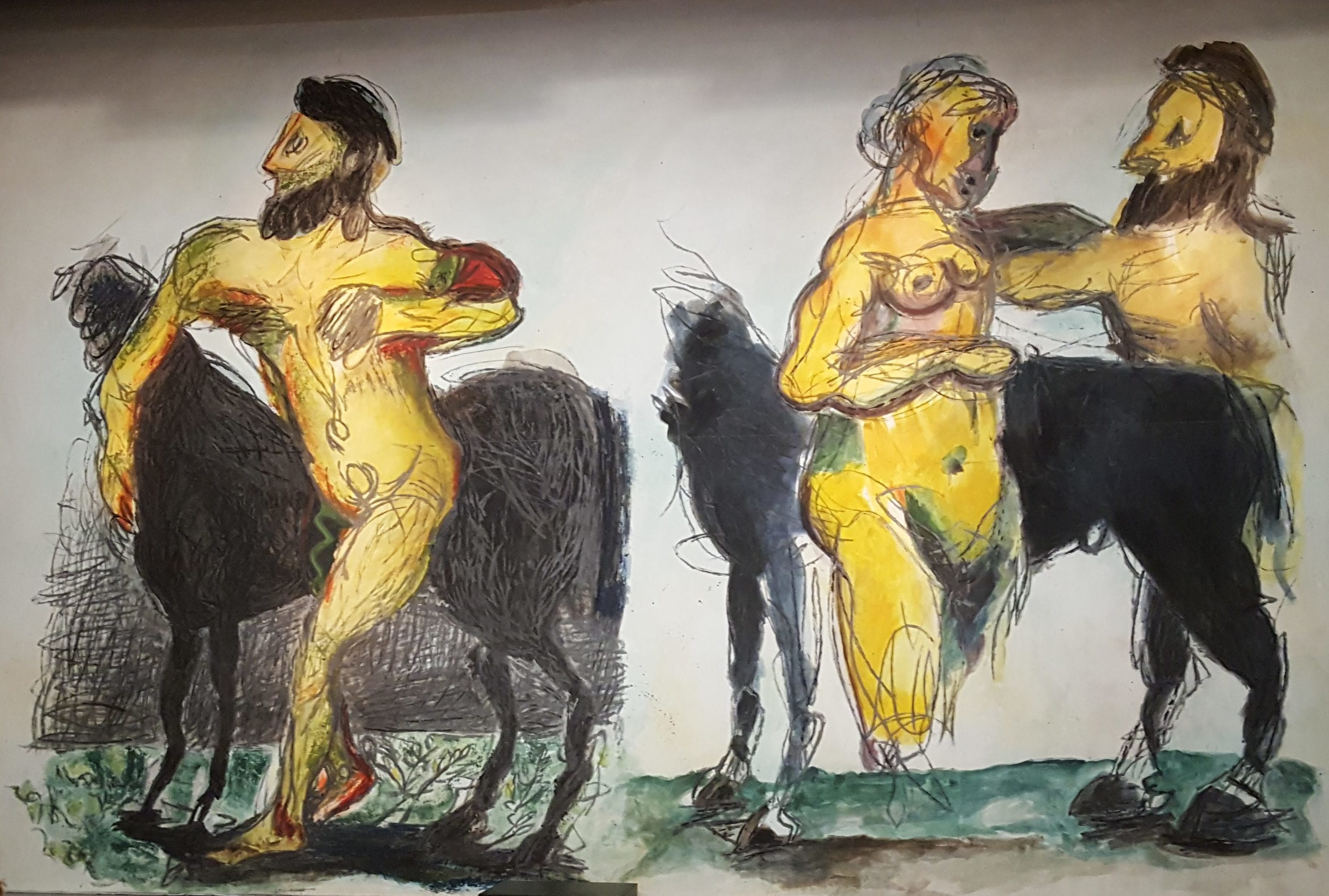

The painting on the scrim at the proscenium set the psychoanalytical tone for the evening

However, the expressionist-style painting on the scrim at the front of the stage gave us an inkling of what we might expect from tonight’s performance: lots of psychological angst expressed through passionate, Romantic music–an artistic approach that is stereotypical of German opera productions. The opera, as its name implies, is a series of separate scenes with no narrative thread to stitch them together, so it almost begs for a psychoanalytical interpretation to lend coherence. And considering that Robert Schumann wrote this response to Goethe’s Faust while slowly descending into mental illness, any angst should not come as a surprise.

Not having access to a synopsis, we felt some relief when English supertitles appeared above the proscenium as the curtain rose. However, whenever the dialogue switched from sung to spoken–which happened frequently in this atypical opera–the supertitles failed to appear, so it was almost impossible for us to make sense of what was going on. The expressionist set and costume design provided some clues, but in terms of the story, we were completely lost by the third of the opera’s thirteen scenes. Once we abandoned our attempts to understand what it all meant and simply focused on the music, however, we were able to relax and enjoy it. Schumann’s music was indeed glorious, with singers and instrumentalists who did it justice. And if we may be forgiven for being a bit biased, we would say that the excellent chorus sounded particularly well-prepared.

Leave A Comment