We still find it hard to fathom that when we arrived in Auckland fourteen hours after leaving San Francisco, clocks at the airport showed a thirty-two hour difference: it was 5:30 a.m. on Saturday 11 January. Our second missionary miracle is that although we’ve had to perform some mental gymnastics to maintain temporal equilibrium, it didn’t take long for our bodies to adjust to having vaulted over so many time zones.

Automated passport control at Auckland airport

Lots of improvements have been made at the Auckland airport since we arrived there on vacation six years ago, when we had to wait, and wait, and wait for our turn at the passport check station. Passport control is now entirely self-help, with electronic scanners to validate each arriving passenger. Customs control took a little longer, especially since we had indicated that we were bringing in more than the usual amount of prescription medications. We had been told to bring the full two years’ worth, so we were chagrined when the customs agent said that we should have been limited to a three-months’ supply. However, when we explained that most of what we had was prescription ointment for Nancy’s skin condition and not addictive drugs, the agent waved us through.

Missionaries come to the Missionary Training Centre in Auckland from all over the South Pacific and parts of Asia. Many are learning to speak English

Our friends Barry and Eva G, directors of the Matthew Cowley Pacific Church History Centre, were waiting for us and had wisely brought a van; somehow they knew that all our luggage would not fit into their Camry. On our way to Hamilton, they took us by the Auckland MTC and the site where construction has just begun on the new Auckland Temple. No workers were there so early in the morning, so there wasn’t much to see besides earth-moving equipment, but the hilltop location commands an impressive view.

Our home for the next two years

When we arrived in Hamilton 90 minutes later, the Gs drove us by the flat that would be our home for the next two years, but immediately went on to the Matthew Cowley Pacific Church History Centre so we could get the lay of the land. Barry pointed out landmarks and gave us some advice for navigating New Zealand’s ubiquitous traffic roundabouts. Then he drove back to our flat, handed us keys for the house and for the Toyota Corolla Hybrid parked in the garage, and told us to take all the time we needed to rest and unpack. He and Eva then went home to eat breakfast before opening the Centre for the day.

Our Toyota Corolla hybrid

Inside our Toyoto Corolla hybrid. Note the placement of the driver’s side

Nancy was only too glad for a chance to “get horizontal” (as her grandmother used to say). Although she had slept a few hours on the plane, she still had a cold and felt a little nauseated after the long flight. While Nancy napped, Michael mustered the courage to drive into central Hamilton (about 3 kilometres away). Eva had picked up two SIM cards with 30 days of free phone service to get us started, so, thanks to the Toyota’s onboard GPS, Michael found the urban mall where the phone store is located and asked to set up a consolidated account that included wifi for the flat. Sorry. The clerk wouldn’t even begin the transaction without seeing Michael’s passport (which he had left at home), and Nancy also needed to be physically present to consolidate the accounts. However, even though he failed to accomplish the specific task he had set for himself that morning, Michael did not feel like a failure because he had successfully driven through downtown traffic on the wrong—er . . . the left side of the road.

Later, when we both returned to the phone store with our passports, we learned that this particular service provider required us to have a New Zealand bank account—a complication we had hoped to avoid—so we decided to try a different provider. The salesperson at the second company not only offered us a better deal without requiring a NZ bank account, but because she recognized our missionary name tags (she, too, was LDS) she gave us their best discount on two phones and broadband service (which is what the Kiwis call internet or wifi service).

Baan Thai restaurant, Victoria Street, Hamilton

Not long after Michael returned from downtown on our arrival day, Nancy woke up feeling much better—although neither of us felt like eating anything more than a piece of fruit from the bowl that Eva and Barry had left us as a housewarming gift. About 3:00 p.m. we drove over to the Centre (about 5 kilometres from our flat) to meet the other missionaries and volunteers with whom we will be working, and then Barry and Eva took us out to an early dinner at Baan Thai, a restaurant in central Hamilton.

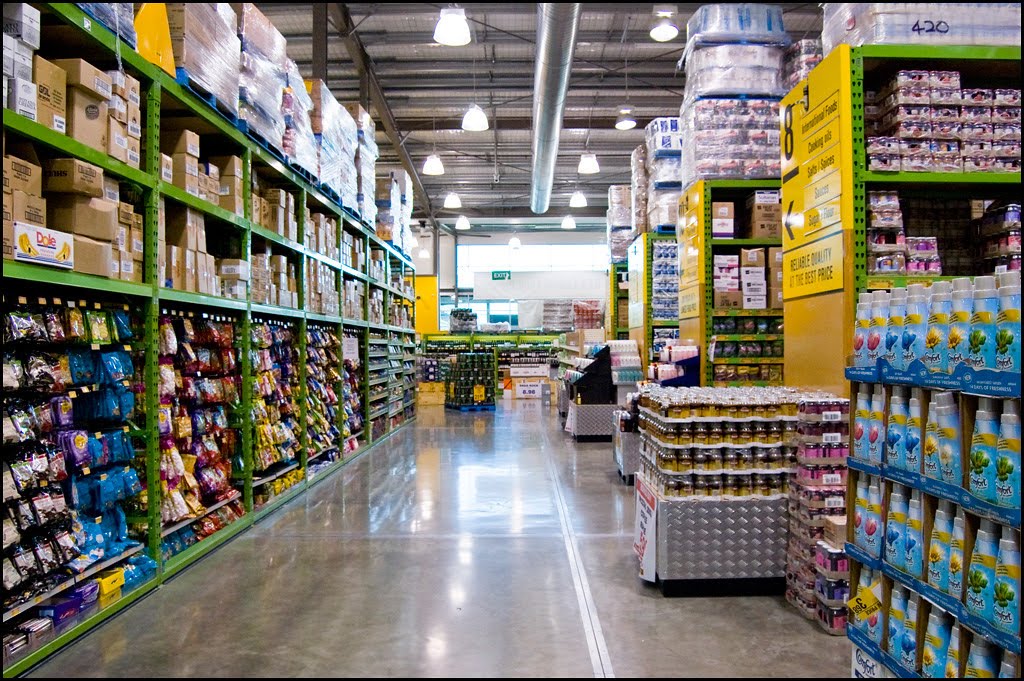

Pak ’n Sav’s warehouse-like approach to grocery shopping

After dinner we went to Pak ’n Save, one of NZ’s large chain grocery stores, and tried to think of everything we would need to survive at least through the next few days: milk, eggs, orange juice, cereal, bread, peanut butter, carrots, fruit, salt, pepper, dish detergent, toothpaste, shampoo, toilet paper—just try to imagine what would be on your shopping list if you had brought no food or household basics and the only commodities left in your cupboards by the previous residents were a bottle of toilet cleaner, a bottle of permethrin concentrate (for killing fleas), and a tube of dried-up mascara.

We loaded our shopping cart (called a trolley here) and then wearily unloaded it at home, hoping that the food we had bought wouldn’t strain the limitations of our diminutive refrigerator-freezer. By 9:30 p.m. we were in bed and asleep. Our third missionary miracle: we both slept like logs until about 5 a.m.

So, you probably want to ask, how have we adjusted to life in New Zealand?

The “Great Room” in our open-design flat

Our bedroom is just that: the room with the bed in it

Our compact bathroom

Our first adjustment has been living in a spartan missionary flat rather than a well-appointed two-story house with a full basement and a big yard. Granted, we have an unusually large missionary flat—three bedrooms—but hardly enough furniture to fill even one room. In the living/dining room we have a small couch, a small recliner, a floor lamp, a small kitchen table, and four plastic stackable chairs. In one bedroom there is a queen-size bed and a small dresser that functions as a nightstand. In another bedroom there is a bookcase, a folding table that functions as a desk, and two more stackable chairs. In the third bedroom, there is a larger dresser, a couple of portable electric heaters, a floor fan, an ironing board, and a folding laundry rack.

Our washer and dryer are in the garage (pronounced with the accent on the first syllable)

Also unusual for a missionary flat is the fact that we have a garage; it holds one car, a small washer and dryer, and a small recycling bin. Out the back door is a small patio, a clothesline, and a strip of low, greenish vegetation that purports to be a lawn. Did you notice how often we used the word small as a descriptor?

Windows without screens

To this picture, add the fact that our missionary flat is in New Zealand, where windows open from hinges at the top, and do not have screens. Because our flat has no central HVAC system, the only way to get air flowing is to open the windows, so all manner of small creatures are free to enter at will. Fortunately, New Zealand seems to have fewer bugs than Ohio—although we’re currently in the dry season, so it remains to be seen whether the insect population will increase when the rainy season begins in March. We have been warned that the rainy season also brings mold (spelled mould), so we’re supposed to leave our curtains and windows open as much as possible, even when it’s cold. Right now it is mid-summer, so high daytime temperatures are typically in the mid to upper 80sF), but at night they usually drop into the low 50s. The wind blows frequently, but we’ve seen very little rain.

The clothesline barely fits in our backyard

We were happy to see a washer and dryer in our garage, even though they have about half the capacity of the ones we left in Cincinnati—which means that we do laundry about twice as often. We also were happy to see that the cooktop is gas, except that the flames are so high even when turned down to the lowest level that “simmering” just isn’t possible. We still have not determined what all the pictograms on the electric oven controls represent because we can’t find instructions for our outdated model anywhere online. The sink is not big enough to wash a day’s worth of dishes, so we use the dishwasher every day—a big change from the once-a- week schedule we used to get by with. There’s no garbage disposal, so we had to buy a can with a tight, pop-up lid for our onion skins, plum pits, and carrot peelings.

Our colourful tableware

The mission office supplied us with plates, glasses, and other dinnerware—all completely mismatched. Initially, food preparation processes with the tools at hand felt closer to camping than home cooking, but they have become our new normal. None of our knives are any good, so we invested in a sharpening steel that has made some difference, but Nancy is still on the hunt for better blades at a decent price. We requisitioned an electric mixer, laundry basket, and mop from the mission housing coordinator, who has done his best to help us feel comfortable despite the fact that the comforter he spread on our bed is twin-size rather than queen. But, after several more shopping excursions, we now have an apartment that feels like home.

Electrical sockets, each with its own off/on switch

We still have to remind ourselves to turn electrical sockets on when we plug cords into them, because every outlet has an adjacent on/off switch. Too many times have we discovered that the phones we thought were recharging were simply languishing on the counter, unconnected to any electricity. But, we eventually discovered that the mystery on/off switch under the dashboard of our car powers a wireless phone charging station, so we can power up as we travel.

Mitre 10, a close cousin to Home Depot

Recently, we were excited to find a way to overcome another minor household inconvenience. Our bathroom facilities are divided into a bath/shower/sink room and a separate WC for the toilet. This in itself is not an inconvenience, except that the WC is lit only by a glaring overhead light, which makes nocturnal visits difficult. We bought a nightlight, but then realized that the WC has no electrical outlet. Next, we tried to find a very low-wattage bulb to fit in the overhead socket, but had no success. Using a flashlight (here, a torch) seemed our only nighttime alternative, but there is nowhere but the floor to set it down.

Glowing toilet

But then, on a recent visit to Mitre 10 (NZ’s equivalent of The Home Depot, with an identical aisle layout and the same orange-and-black color scheme as its American counterpart), Nancy found a brilliant solution: a battery-powered, motion-sensing light especially designed to hang over the edge of a toilet bowl. So now when we visit the loo, we are greeted by a toilet bowl softly glowing with a changing display of rainbow colours.

Other than finding the right stores for the kinds of things we needed to buy, shopping has not been much different than in the States. Pak ’n Save is very much like WinCo (a western U.S. discount grocery chain; Ohio doesn’t really have anything comparable).

Our local grocery store

The Warehouse

Countdown, close enough for us to walk to, is more like Kroger or Smith’s. For housewares and office supplies, The Warehouse is the place to go—it’s kind of like Costco without the fresh foods. K-Mart does not have the seedy reputation here that it does in the States; we found quite a few useful items there. Briscoes is a little more upscale, as is Bed Bath and Beyond, which offers a 30-percent discount on everything if you sign up for their loyalty program—no coupons required.

Currency conversion is about $1.5 NZD to $1 USD. Most things are more expensive here, except fuel (petrol) and eating out, which we’ve done fairly frequently because Barry and Eva keep either telling us about restaurants we need to try, or taking us there themselves. Hamilton has lots of good Asian restaurants, and of course, the seafood is amazing.

Nancy planted a potted herb garden

Another amazing thing is the fresh fruit, which is very tasty. We have had extraordinary nectarines, peaches, plums, passion fruit, and pineapple (sold with the leaves already chopped off). Tomatoes taste like tomatoes, and strawberries like strawberries. Carrots are fatter and celery is greener, but the dark stalks don’t taste bitter, as they tend to do in the U.S. Zucchinis are known as courgettes (pronounced not with a soft g as in French, but with a hard g as in Cougarettes), and nearly every other variety of squash, no matter what size or color, is called “pumpkin.” Bell peppers of all colors are called capsicums. There are more varieties of sweet potatoes (kumara) for sale here than regular potatoes.

Eggs come in many more carton configurations than in the U.S., and they are not refrigerated

The meat and dairy sections of the stores have presented us with some challenges. There is a greater variety of meats, including goat and “offal,” but the more familiar beef, pork, lamb, and chicken come in different cuts with unfamiliar names, so often the only thing we have to guide our selection is the price. All ground meat is called mince. In the dairy department, low-fat items are either much more expensive or nonexistent, so we’ve tried to cut back a little on our consumption of cottage cheese, yogurt, and cream cheese. (We can get 1-percent milk, however.) Margarine is unheard of in this land of dairy farms, and that’s fine with us; even commercially packaged cookies are rich with the taste of fresh butter. Another item that’s missing from the dairy case is eggs—not because eggs are unavailable, but because they are not kept refrigerated. Nearly as disconcerting is that they aren’t graded according to size, but according to weight, and they don’t come in dozens, but in cartons containing even numbers from four to eighteen.

Michael was distressed to learn that apparently chocolate chips are not sold here, so he has had to make do with chopping large chocolate bars into small pieces. Actually, the lack of chocolate in the form of chips has not been a serious problem because we don’t have a cookie sheet, and even if we did, it would not fit in our diminutive oven, so Michael has been content with making brownies and chocolate cake instead. He also has been doing an extensive research study on ice cream, evaluating various flavors and brands everywhere we go.

When our alarm goes off at 6:30 a.m., we get up and go walking around the neighborhood for half an hour before breakfast, clocking 3-4 km each day (which Michael hopes will offset some of the ice cream, buttery cookies, and chocolate he’s been consuming). Sometimes it’s cloudy when we leave, but we always wear sunglasses and hats because the sun is likely to break through before we get home. The quality of light here is unlike anywhere else we’ve been: blindingly bright, because we’re directly under the hole in the earth’s ozone layer. Nancy’s dermatologist advised us to use sunscreen religiously because New Zealanders have a very incidence of skin cancer, and we have taken her counsel seriously.

Side-by-side workstations in our flat

Side-by-side workstations at the Centre

One of the most difficult adjustments for us has been being together 24/7. Once we have showered, dressed, and eaten breakfast, we drive to the MCPCHC together and sit down at our adjacent desks in the Centre’s workroom. We break for lunch together around noon, eating sandwiches or leftovers we have brought from home in the lunchroom (the only place in the building where food is allowed); and after the museum closes at 5 p.m. we drive home together. One of us cooks dinner (because the kitchen is too cramped for more than one person to work at a time), while the other takes care of U.S.-based business (it’s tax time!). After dinner we clean up together, sometimes do laundry, and often we both end up sitting next to each other at the table in the study where our laptops are set up until it is time to go to bed. When we need to go to the store or run other errands, we almost always go together because Nancy is not yet comfortable driving in city traffic.

We are becoming accustomed to driving on the opposite side of the street

Michael has been doing remarkably well behind the wheel, as long as he stays focused. Local etiquette dictates that one use the right turn signal when entering a roundabout, and the left turn signal to exit. Both of us have found that full concentration is required to remember that the turn signal is on the right of the steering wheel, so more often than not we accidentally set the windshield wipers going when approaching a roundabout because the wiper control is located on the left. At intersections with traffic signals, there are always separate lights for going straight, turning left, and turning right. The trick is remembering to look at the correct light, but Michael is getting the hang of it. When we are out walking, we remind each other to look to our right first before crossing the street.

A roundabout near our flat

In terms of our actual work at the MCPCHC, we each have different responsibilities and daily tasks, but we can’t help overhearing each other’s phone conversations and discussions with other staff, so we are fully aware of what the other is working on. Both of us quickly realized that the positions we are filling are, in truth, full-time jobs. Neither of us has worked a 9-to-5 job for a long time—in Nancy’s case, decades—and it hasn’t been easy to readjust to that kind of daily schedule. Another mental adjustment required of us stems from the fact that because the MCPCHC is closed on Sundays and Mondays, our work-week goes from Tuesday through Saturday. Having our “weekend” at the beginning of the week has been even more disorienting than summer in January! We’ll provide more details about our work at the Centre in a future post; for now, we’ll just say that about the only thing we do that resembles what the young, proselyting missionaries do is put on missionary attire and name tags each morning.

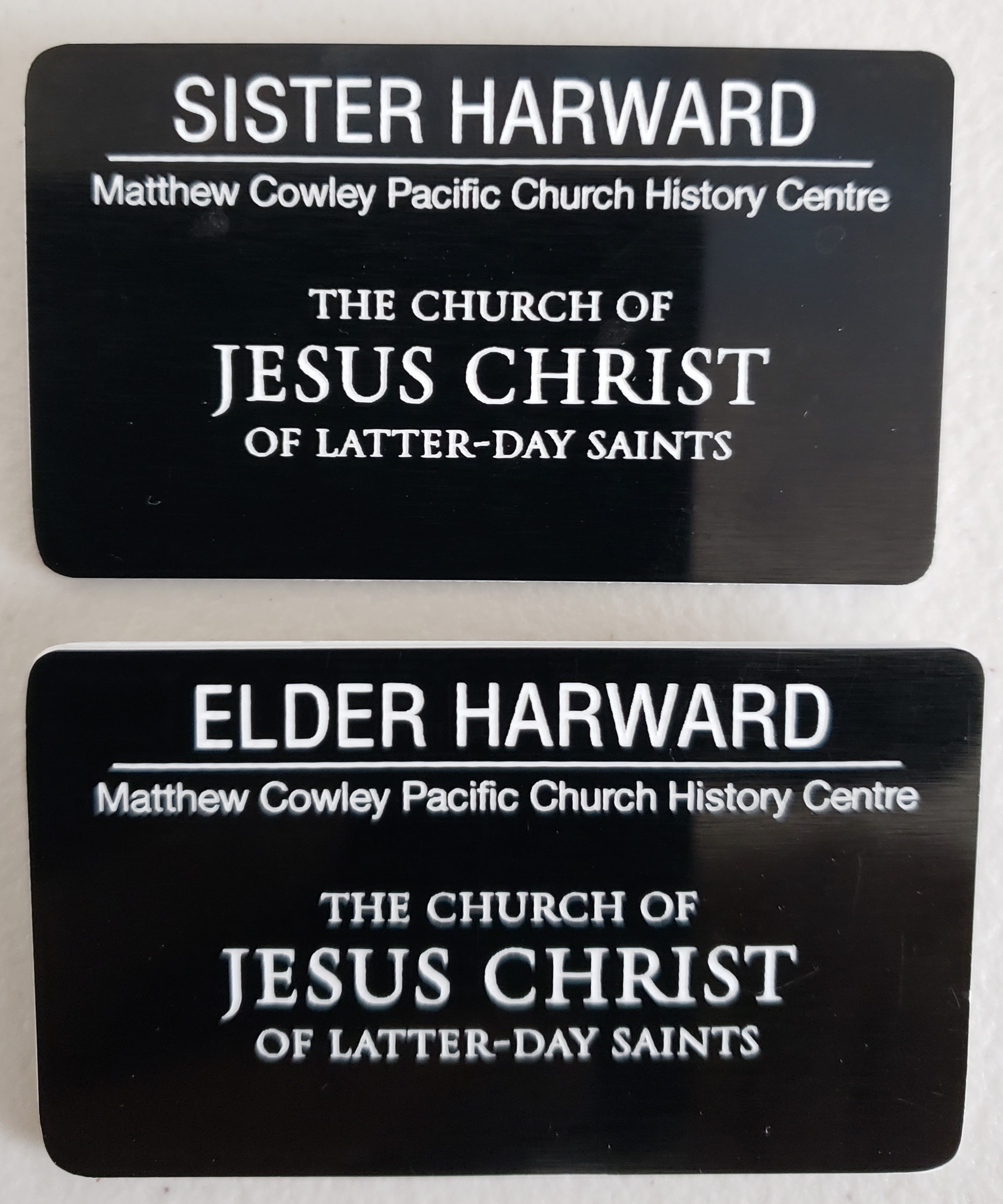

Our name tags

Wearing a suit, a white shirt, and a tie to work has been another major adjustment for Michael, but we have grown to like wearing our missionary name tags. Because of them, Church members (pronounced Chirch mimbehs) smile and greet us wherever we go, and curious non-Latter-day Saints often ask questions that we’re happy to answer. The LDS population makes up about the same percentage of the general population in New Zealand as in the U.S., but the percentage of LDS in Hamilton is much higher, almost like that of Utah. There are four stakes (dioceses) in the Waikato Region (of which Hamilton is the major city), which has a population of 165 thousand. (In contrast, Greater Cincinnati has only three stakes for a general population of 2.5 million.) The Hamilton area has so many LDS because lots of young men and families came here to help build the Church College of New Zealand and the temple during the 1950s, and then stayed. (We’ll tell more about that construction project in a future post, because it’s a fascinating, inspiring story.) New Zealand was a fruitful field for the LDS missionaries who began arriving in the second half of the nineteenth century, their message resonating especially with the Maori people who had begun populating the islands they called Aotearoa in the thirteenth century. (That’s another fascinating story that you can look forward to.)

Today, the Maori and Pakeha (whites of European ancestry) seem to be quite well integrated in the Church and beyond. The Maori language, which Pakeha colonizers did their best to snuff out in centuries past, is making a comeback, thanks in part to immersion schools (similar to what we saw in Ireland). Maori appears more often than English in the names of natural landscape features, towns, and villages, and very often in the names of city streets. We see Maori on billboards, in company names, and in consumer products, and we’re beginning to understand some of the more common phrases in public signage (e.g. haere mai, which means welcome, and tane and wahine, which distinguish men’s and women’s wharepaku—toilets). Maori has consistent phonetic spelling, with vowel sounds much like those of Spanish, so it shouldn’t be hard to pronounce, but because names tend to be multisyllabic, we are still having trouble distinguishing and remembering all the syllables in the names of the people we meet or the places they suggest we visit. Other things we’ve learned about the Maori language: the first syllable is always accented; there are no sibilants, and no b, d, j, l, q, x, or y sounds; wh is pronounced as f in English; g is used only in combination with n, and ng is pronounced as at the end of sing—and that ng sound is just as likely to begin a word as to end it. (Now try pronouncing Ngaruawahia, the name of a town near Hamilton.) Repeated syllables signify amplification, so two repetitions mean bigger or better, and three repetitions mean biggest or best. So teiteitei (three repetitions of tei) means tallest, and Whatawhata, a locale in the Hamilton area situated on a land formation that resembles a shelf, means big shelf. (Whatawhata looks amusing in English, but it’s almost funnier when pronounced properly in Maori: Fatafata).

Just as challenging as wrapping our tongues around Maori has been trying to understand the distinctive vocabulary and idioms of Kiwi English. Here are a few new phrases we have picked up:

- “we’ll get it sorted” = “we’ll figure it out”

- “there were heaps of people” = “there were a lot of people”

- “good on you” = “good for you”

- “give her a lolly” = “give her some candy”

- “we didn’t have the right to bowl it” = “we didn’t have permission to demolish it”

- “she’s nipping to the shop” = “she’s making a quick trip to the store”

- “he’s a keen bean” = “he’s eager”

- “have a go at it” = “try it”

- “musical item” = “musical number”

- “take it to the panelbeaters” = “take it to the collision repair shop”

- “I’m really cut up” = “I’m really upset”

- “get it at the dairy” = “get it at the neighborhood convenience store”

- “this is machine is stuffed” = “this is machine is broken”

- “clear-away M-F 3-6 p.m.” = “no parking M-F 3-6 p.m.”

What does “No fly tipping” mean?

Most local idioms we can “sort out” in context, but others have left us completely stumped. One that even the Kiwis working at the Centre couldn’t interpret for us was on a sign we saw behind a store: “No fly tipping.” We had to google the phrase to learn that it meant “No dumping of trash.”

There’s an important Maori phrase that we learned even before we arrived. We had heard Barry and Eva refer to it in connection with the Matthew Cowley Pacific Church History Centre, and we saw a wooden plaque bearing the phrase hanging in Tiffany’s office in the Church History Museum in Salt Lake. The phrase had been the motto of Matthew Cowley, a young Latter-day Saint who was sent from Utah to New Zealand in 1914 to take the restored gospel of Jesus Christ to the Maori people. He was only 17 years old, knew no one here, had no companion, and did not speak the language—but he had tremendous faith that the Lord would help him succeed. He did succeed—through faith, determination, and living by a motto he had learned from the Maori: Kia ngawari.

Literally, Kia ngawari means Be easy, but that simplistic translation can’t begin to capture the full meaning of the phrase. In this case, easy does not mean uncomplicated, or carefree, or (heaven forbid!) morally loose; rather it means something closer to the combination of character traits the Book of Mormon prophet Alma described when he was teaching the people of Gideon: “Now I would that ye should be humble, and be submissive and gentle; easy to be entreated; full of patience and long-suffering; being temperate in all things; being diligent in keeping the commandments of God at all times; asking for whatsoever things ye stand in need, both spiritual and temporal; always returning thanks unto God for whatsoever things ye do receive. And see that ye have faith, hope, and charity, and then ye will always abound in good works (Alma 7:23-24).

Literally, Kia ngawari means Be easy, but that simplistic translation can’t begin to capture the full meaning of the phrase. In this case, easy does not mean uncomplicated, or carefree, or (heaven forbid!) morally loose; rather it means something closer to the combination of character traits the Book of Mormon prophet Alma described when he was teaching the people of Gideon: “Now I would that ye should be humble, and be submissive and gentle; easy to be entreated; full of patience and long-suffering; being temperate in all things; being diligent in keeping the commandments of God at all times; asking for whatsoever things ye stand in need, both spiritual and temporal; always returning thanks unto God for whatsoever things ye do receive. And see that ye have faith, hope, and charity, and then ye will always abound in good works (Alma 7:23-24).

Everyone who visits the Matthew Cowley Pacific Church History Centre learns that Kia ngawari means: Be humble, be gentle, be loving, be kind, be patient, be temperate, be thankful. This is the Maori way. This is the way of Jesus Christ. We are trying to make it our way, too.

Love this post! I’m excited that you’re serving in the South Pacific, working together equally yoked, and that you’re enthusiastic! I know you both will make a tremendous difference there, spark Elijah in a lot of folks, and leave a clear path for others who serve after you. I look forward to your future posts! ❤️ —Sister Stewart

A friend who recently returned from Borneo explained to me that eggs naturally have a protective covering on their shells, a cuticle, & need not be refrigerated unless they are washed as we treat them in the States. Most countries other than the US, Australia, and Japan, do not refrigerate eggs, including EU countries.

I assume that the U.S.D.A. requires all eggs to be washed before they can be sold in the U.S. because even when we buy cage-free eggs from a working educational farm near our home in Cincinnati, they’re kept in a refrigerator case.

All very fascinating…but that green light toilette! If it turns red do you have to “stop?” Haha! I’ve never had trouble adjusting to driving on the “wrong” side, but we never had a car where any of the controls were placed differently than an America car. That turn signal on the right side would throw me for awhile. I guess on a manual transmission the stick is manipulated with the left hand instead of the right, but that never bothered me. I’m very curious to learn about your responsibilities. I’ll be looking for the next post!