Getting through Rome on a Monday morning proved more challenging and time-consuming than it had been on Saturday. The day was as beautiful this morning as then, but traffic was much heavier. The one benefit was that we were able to see—and hear Fabrizio’s commentary on–parts of Rome that were not on our official itinerary.

Tiber River

According to legend, the city of Rome was founded in 753 BC on the banks of the Tiber River, about sixteen miles from the sea. The third longest river on the Italian peninsula, the Tiber was vital to Rome’s development as a commercial power. It was used to ship grain as early as the fifth century BC; eventually barges loaded with other foodstuffs, stone, and timber floated down the Tiber to markets in Rome. By the seventeenth century, however, silting had become a problem, and today the river is navigable only as far as Rome itself. Flooding also has been an issue, which is why the Tiber is confined within high stone embankments as it flows through the city.

Castel Sant’Angelo

The imposing Castel Sant’Angelo stands on the Tiber River. Built by Hadrian around 135 AD as a family mausoleum, it eventually became a papal fortress as well as a prison. Its current name (Castle of the Holy Angel) was applied in the late sixth century, after the Archangel Michael supposedly appeared on its rooftop and sheathed his sword, declaring an end to the plague that had devastated Europe.

Circus Maximus all ready for Susan Komen

Driving along part of the ancient Appian Way, we passed the Circus Maximus, which was built in antiquity as a venue for chariot racing. Today the space was filled with white canopies set up by vendors and teams participating in a Susan G. Komen Race for the Cure. We also passed the ruins of the Caracalla Baths, whose soaring barrel vaults made it the model for countless public halls, including New York City’s Penn Station.

Altare della Patria

The conspicuous Altare della Patria (Altar of the Fatherland) is a national monument to Victor Emmanuel II, first king of modern unified Italy, and includes the tomb of an unknown Italian soldier killed during World War I. Its construction, completed in 1925, angered archaeologists because it destroyed the remains of a medieval-era residential neighborhood. Romans deride the building, glaringly visible from all over the city, as “la torta nuziale” (the wedding cake).

Umbrella pines on the edge of the Circus Maximus

Roman pine trees are unlike those in northern forests. Called stone or umbrella pines, they are native to the Mediterranean and have been cultivated for their edible nuts since prehistoric times. We were prompted to ask: If the custom of decorating evergreens for Christmas had begun in Rome rather than in Germany, would our Christmas trees be shaped like Tootsie Roll Pops instead of inverted ice cream cones?

Palazzo Orsini

Pontificia Univeristà della Santa Croce, administered by Opus Dei

Another walking tour ensued after the bus dropped us on the south side of the Tiber, near a hotel that was formerly the palace of the Duke of Orsini. A few minutes later, Fabrizio stopped us in front of complex of buildings that looked unremarkable until he explained that they constituted the Pontifical University of the Holy Cross, founded in 1984 by Opus Dei (Work of God). This Roman Catholic organization is similar to an order for priests or nuns, but is designed for lay people rather than the ordained, teaching that everyone is called to holiness and that ordinary life can be a path to sanctity. (Unfortunately, Dan Brown and The DaVinci Code have sensationally warped our understanding of what Opus Dei is all about.)

Piazza Navona

The long Piazza Navona is graced by three fountains. In the center is the Fontana dei Quattro Fiumi (Fountain of Four Rivers), another example of the work of the prolific Gianlorenzo Bernini. Its main figures represent major rivers of the four continents through which papal authority had spread by the seventeenth century: the Danube for Europe, the Nile for Africa, the Ganges for Asia, and the Río de la Plata for the Americas.

The Nile

Fontana dei Quattro Fiumi

The figure representing the Nile in the Fountain of Four Rivers (left) is covering his head, indicating that the source of the Nile was unknown when the fountain was constructed in 1651.

The obelisk in the middle of the Fontana dei Quattro Fiumi dates from around 80 AD. It was probably commissioned by Domitian and is known to have been placed in four other locations, including the Circus Maximus, before it ended up here.

The Church of Sant’Agnese in Agone

The Church of Sant’Agnese in Agone on the Piazza Navona marks the site where St. Agnes, patron saint of virgins, was martyred at age twelve for refusing to offer sacrifice to a pagan god.

The Fountain of Neptune

The Fountain of Neptune in Piazza Navona was once known as “Fontana dei Calderari” (Fountain of the Heat-Generators) because it was near a street full of blacksmith shops.

Palazzo Madama was built for the Medici family in the 15th century. It is now home to the national Senate

A painting of the Virgin Mary watches over an intersection near the Palazzo Madama. Such roadside icons are common throughout Rome

A few more blocks (the term must be used loosely in areas built up from ancient, irregular footpaths) took us past the Palazzo Madama, the heavily-guarded former Medici palace that currently serves as home to the Italian Senate.

Emblem of the municipality of Rome

The letters SPQR appear all over the city, on everything from gates to manhole covers. When we inquired, Fabrizio explained that they stand for Senatus Populus Que Romanus (The Senate and People of Rome) and are the emblem of the municipality of Rome.

Our primary destination for the morning was the Pantheon, a marvel of ancient engineering that has stood pretty much intact since 125 AD.

Pantheon

Inside the Pantheon

The oculus in the dome of the Pantheon

It features what is still the world’s largest dome constructed from unreinforced concrete. The stone used in the concrete aggregate gets progressively lighter from the base to the crown: travertine at the bottom, terracotta tile shards in the middle, and pumice toward the top. To further reduce stress on the foundation, the crown of the dome is completely open. The oculus, 27 feet in diameter, provides light and air to the Pantheon’s interior. Rain gets in, too, but that never seems to be too much of a problem; the interior floor slopes toward drains at the edge of the outer wall. Entrance to the rotunda is through a portico supported by twelve granite columns, each of which is nearly forty feet tall and weighs sixty tons. These monoliths came from a quarry near Luxor, Egypt, and were transported up the Nile and on to Rome by barge. Fabrizio told us that they were packed in lentils to protect them from damage during the journey.

Columns surrounding the entrance

The Pantheon was originally a pagan temple, though probably not dedicated to all gods, as its name seems to imply. By the seventh century, it had become a Christian church dedicated to Saint Mary and the Martyrs. The twelve niches around the rotunda that once contained statues of Roman gods now contain monuments to various saints and Christian dignitaries, including the Renaissance artist Raphael, who is entombed there.

The Madonna di Sasso stands above Raphael’s sarcophagus in the Pantheon

The sculpture in the niche above Raphael’s sarcophagus, Madonna di Sasso (Madonna of the Rock), was commissioned by the famous artist before his death in 1520 and executed by an associate named Lorenzetto.

A wooden crucifixion scene hangs near the entrance to the Pantheon

Sant’Ignazio di Loyola

The “domed” ceiling of Sant’Ignazio di Loyola

We visited one more church this morning: Sant’Ignazio di Loyola, built in the seventeenth century. Ignatius was the founder of the Jesuit order; the Roman College adjacent to the church served as a kind of Jesuit missionary training center until the facility was taken over by the government in 1870. The college lacked the funds to build a dome for the church, so they faked it: what appears to be a soaring domed ceiling is actually a trompe l’oeil (fool the eye) canvas painting. The church is exemplifies the ornate Counter-Reformation Baroque style, with which the Catholic Church sought to lure Protestant-leaning parishioners back to the fold.

Linda whispers to Budge in the ornate Church of St. Ignatius of Loyola

Tomb of a young Jesuit in the Church of St. Ignatius of Loyola

The tomb of a young Jesuit who died in 1591 while tending to others afflicted with plague (at right) is a particularly gaudy example of the style.

Bureau for the Protection of Cultural Heritage

Outside the Church of St. Ignatius, on the opposite side of the Piazza di Sant’Ignazio di Loyola stands another example of baroque architecture: the Bureau of the Carabinieri Command for the Protection of Cultural Heritage (the fashion police?).

Bureau for the Protection of Natural Processes? The coffee shop where we used the W.C.

On our way back to meet the bus at the spot where we had left it earlier, Fabrizio stopped outside a coffee shop and gave us ten minutes for a bathroom break. There was only one W.C., which meant that each of us was allowed 25 seconds to get in and out. We almost succeeded!

The French Embassy and the Centre Saint Louis are located, appropriately, on Joan of Arc Street

The reason for getting back on the bus was to ride to a parking garage near the Vatican, where we were scheduled for a special tour later this afternoon. We probably would have been better off walking. Checking a map later, we realized that the parking garage was just over a mile from where we had started, but midday traffic in central Rome was so bad that the ride had taken about 45 minutes. (At least the bus offered an air conditioned place to sit down.) Fabrizio led us (on foot) to the spot just off the Piazza di San Pietro where we were to meet at 2:30 for the tour. Both he and Jim emphasized that we must not be late! Then they turned us loose to find some lunch.

Jeff J and Michael at Hostaria San Pietro

Our lunch at Hostaria San Pietro

Michael is fluent in San Pellegrino, too

Nancy prefers acqua naturale and was not squeamish about drinking it from a public fountain

We accompanied Cathy and Jeff to a sidewalk café called Hostaria San Pietro, located just on the other side of a long pedestrian underpass on the south side of the Vatican. Michael’s spinach-stuffed ravioli were gigantic–two filled an entire plate; Nancy’s risotto with zucchini was topped with a generous number of jumbo shrimp and tiny squid. (Maybe too generous.)

Nobody was late for the special Vatican tour. Nancy definitely didn’t want to miss it because we had tickets to visit the Scavi, the maze of tombs and mausoleums that have been excavated directly underneath the nave of St. Peter’s Basilica.

Such tickets are not easy to get; no more than 250 visitors per day are granted entrance to this necropolis, and reservations must be made months in advance. Jim and Carol had told us repeatedly how lucky we were to secure a place on the schedule. Even Fabrizio was excited, because in the fifteen years that he’s been leading tours around Rome, he had been inside the Scavi only twice before.

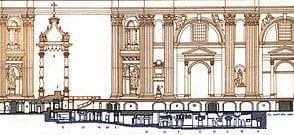

The Scavi (necropolis) in relation to St. Peter’s Basilica

Besides the difficulty of getting tickets, what makes this necropolis so intriguing? The primary reason is that this is thought to be the final resting place of the remains of St. Peter.

Budge and Michael wait outside the Ufficio Scavi (Excavations Office) for our turn to go inside; the Gee Group had to divide in two because tour groups are limited to only twelve visitors at a time

In 64 AD, a terrible fire destroyed most of Rome, and Emperor Nero (who may or may not have been fiddling at the time) decided to blame the conflagration on the Christians, who had been preaching that the great city would someday be burned for the wickedness of its people. As one of the most prominent representatives of Jesus Christ in the Empire, Peter was apprehended and put to death, likely by crucifixion, the method normally used for non-citizens, and probably in Nero’s Circus, the site of many such executions. Bodies of the executed were buried along a road near the steps of the circus. The area may already have been an established cemetery, but eventually it would include above-ground tombs and mausoleums, visited regularly by relatives of the deceased.

The mausoleums are arranged like shops along a street

Tradition maintains that surviving Christians preserved and passed on their knowledge of the location of Peter’s remains but did not mark the exact site, fearing that it would be desecrated. Once Constantine became emperor and decriminalized Christianity in 313 AD, the faithful were free to establish a shrine in the vicinity. Within the next several years, Constantine himself commissioned the first basilica on the site; most of the old tombs were buried when the ground was leveled for construction. More than a thousand years later, that basilica (or rather, one of its later replacements) would be leveled to make way for the magnificent cathedral that now stands in the Vatican, but Peter’s likely gravesite remains–somewhere underneath it all.

First-century Roman mausoleum in the necropolis with niches for crematory urns

Archaeologists who began excavating the necropolis under St. Peter’s in 1939–and continued doing so in secret throughout World War II–unearthed scores of well-preserved tombs. Our guide told us that the mausoleums contained many more niches for crematory urns than ossuaries or sarcophagi, indicating that cremation probably was more common in imperial Rome than inhumation. Researchers also found holes drilled into the floors, through which visiting family members would pour wine and other libations so the dead could participate in their feasts and memorial celebrations.

The so-called “Egyptian” mausoleum

Most of the mausoleums belonged to pagan families because, as a rule, pre-Constantinian Christians were not wealthy enough to build them; however, a few do display decorations that suggest Christian symbolism. For example, one has a figure that could be either Apollo or Christ; in another, there is a mosaic depicting Jonah being swallowed by a big fish–a story often interpreted as a type of Christ’s death and resurrection.

Our guide–a French woman whose name we don’t recall–told stories and pointed out details for more than an hour as she led us through a series of underground passages. (Persons with claustrophobia are advised to skip this tour, but it wasn’t that bad.)

Shrine of St. Peter’s bones

At last we came to an elaborate shrine that encloses the sepulchre thought to be that of St. Peter. The altar and Baldacchino in the basilica above are located directly above this spot. When it was discovered during the twentieth-century excavations, the tomb was marked with a Greek inscription that read Petros eni (Peter here). The guide told us that the sepulchre was empty when they opened it up, but a hidden recess in a nearby wall contained the bones of a “vigorous” 65- to 75-year-old man, wrapped in remnants of a purple cloth decorated with golden thread–surely evidence that these were the remains of the first Bishop of Rome. As further testimony, the cache of bones included no feet, which would seem consistent with the tradition that Peter was crucified upside down (at his request, because he felt he was not worthy to die in exactly the same way as the Lord); supposedly the Roman guards charged with disposing of the body found it too hard to remove the nails from the apostle’s feet to detach them from the cross, so they just cut them off. All of these fascinating details sound plausible–with the caveat that a couple of centuries went by between the time of Peter’s death and the time somebody led Constantine to the gravesite. Another caveat is that the other half of the Gee Group, who were led through the Scavi by another guide, heard a story with an entirely different set of details. Thus the best we can say is: Maybe this is where Peter is buried, and maybe it’s not.

Basilica di San Paolo fuori le Mura

Considering that this trip was to focus on the travels of Paul, we are a little dismayed that a visit to the Basilica di San Paolo fuori le Mura (Basilica of St. Paul Outside the Wall), where the remains of that apostle are supposed to be interred, is not on our itinerary. We’ve been there before, but it would have been nice to go again now that we’ve learned more about Paul, his ministry, and his travels. Like Peter, Paul was executed in Rome during Nero’s reign. Unlike Peter, Paul was a Roman citizen, and therefore would have been beheaded rather than crucified. According to an old tradition, Paul’s remains were buried outside the city walls on the Via Ostiensis, on property owned by a Christian woman named Lucina. Constantine built a basilica on that site, too, and it went through a series of replacements and enlargements similar to those of St. Peter’s Basilica. In 2009, Pope Benedict XVI announced that the sarcophagus buried under the altar of St. Paul Outside the Wall had been unearthed and opened. He confirmed that it contained bones dating from the first century, along with fragments of a purple linen cloth decorated with gold sequins. There was no skull. (Remains of St. Paul’s head are supposed to be at the Lateran Palace, which we have not visited, either.) Benedict seemed satisfied that they had found the actual bones of the peripatetic apostle–though again, who really knows? While it’s fascinating to consider the possibility that the items on display are literally pieces of sacred history, the important thing is not seeing the bones or the chains or the cross, but remembering the people those relics represent, and honoring their teachings, their examples, their sacrifices, and their faith.

Members of the Pontifical Swiss Guard, the pope’s personal security detail, serve as a sort of military police force for the Vatican

But back to the Vatican. The Scavi tour ends where the “grotto” begins. This is the public crypt containing the tombs of about a hundred former popes, from some of Peter’s earliest known successors to John Paul II. The other hundred and sixty-some popes are entombed in other shrines, mostly around Rome, with a few elsewhere in Europe.

Coat of arms

At right: the coat of arms of the Reverenda Fabbrica San Pietro (Reverend Factory of Saint Peter), the administrative body that oversees construction and maintenance in the Vatican, includes the two keys Christ gave to Peter, a chain representing Peter’s imprisonment, and the papal tiara.

Patiently waiting for the bus

Once the entire Gee Group had finished touring the necropolis and had a chance to use the restrooms (the Vatican’s contain many stalls, but we still had to wait in a long line), we got back on the bus and returned to the Hotel President, where most of us took the opportunity to start packing our bags in anticipation of tomorrow’s flight home. Nancy, hoping to learn exactly what brand of olive oil we had enjoyed so much last night, persuaded Michael to return with her to the trattoria around the corner, but alas! It not only was closed, but was so completely hidden behind roll-down metal doors that we passed it twice before finally recognizing it by the potted plants on the sidewalk.

Dining al fresco at Le Caveau: Judith, Lynn, Michael, Richard, Mark, Nancy, Cathy, Eva, Carol, Barry, Jeff J, and Jim

For our last dinner in Rome, five other couples from the Gee Group followed us to Le Caveau, another restaurant within walking distance of the hotel that had been recommended by TripAdvisor. As some of the first diners to arrive this evening, we were shown to two adjoining outdoor tables, shielded from the street by a trellis covered in sweet-scented jasmine. (Lots of jasmine all over Rome–it’s been heavenly!) Our jovial waiter made sure everyone was happy.

The sun went down and the restaurant’s dramatic lighting came on during our dinner

Michael was puzzled by the translation for a dish called gnocchi con funghi e straccia d’anatra (“potato dumplings with mushrooms and duck rags”) but decided to try it anyway. (It was good choice.) Nancy ordered from the prix fixe menu and thus was served a huge portion of spaghetti ragù (pasta in tomato sauce that was thick with ground beef) and then a more modest chicken breast filet poached in white wine. She also got a plate of grilled vegetables. One of the advantages of the prix fixe menu is that it included dessert, and Nancy really wanted to try the panna cotta. It was silky smooth and perfectly complemented the fresh berries on top. Michael and the rest of our party–some of whom had not yet been to G. Fassi–had their palates set on gelato, however, so off we went again to worship at the Basilica of Frozen Desserts on the Via Principe Eugenio.

Back at the hotel, we reorganized our things and prepared to pack them for the last time. We discarded the maps and ticket stubs we no longer needed, and carefully separated what had to go in our checked luggage from what we could take in our carry-on bags. We’re getting pretty good at this; although we’ve made several purchases in the past eleven days, neither of us had to unzip the auxiliary space in our suitcases.

Leave A Comment