A perfect blue sky was draped over the harbor and the village of Skala when we went topside this morning to enjoy the sunshine and breakfast on Eggs Benedict. (Michael ordered the traditional formulation; Nancy and Mark both chose the Spanish version, made with chorizo sausage, manchego cheese, and saffron-spiced hollandaise sauce. ¡Que rico!)

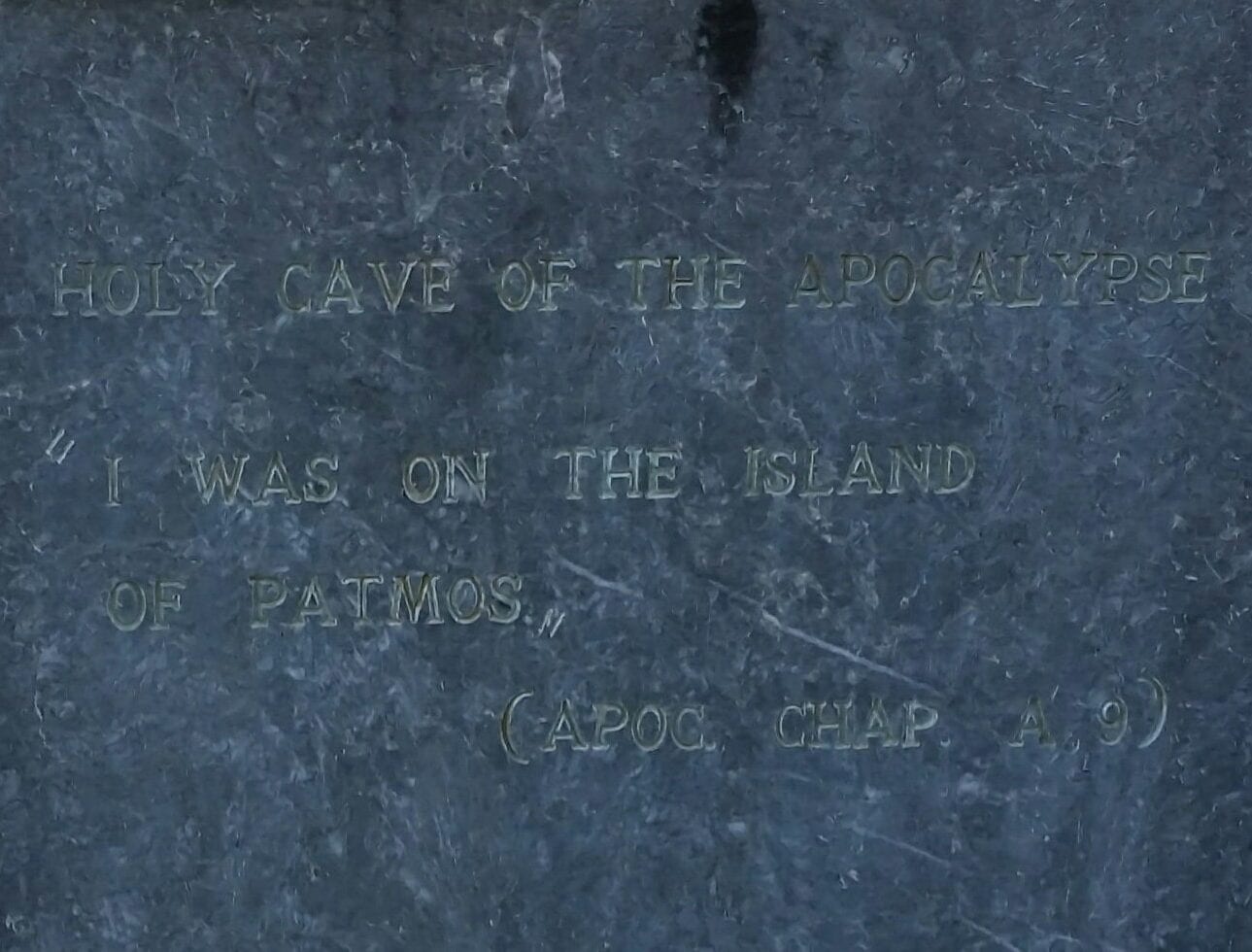

Plaque honoring St. John

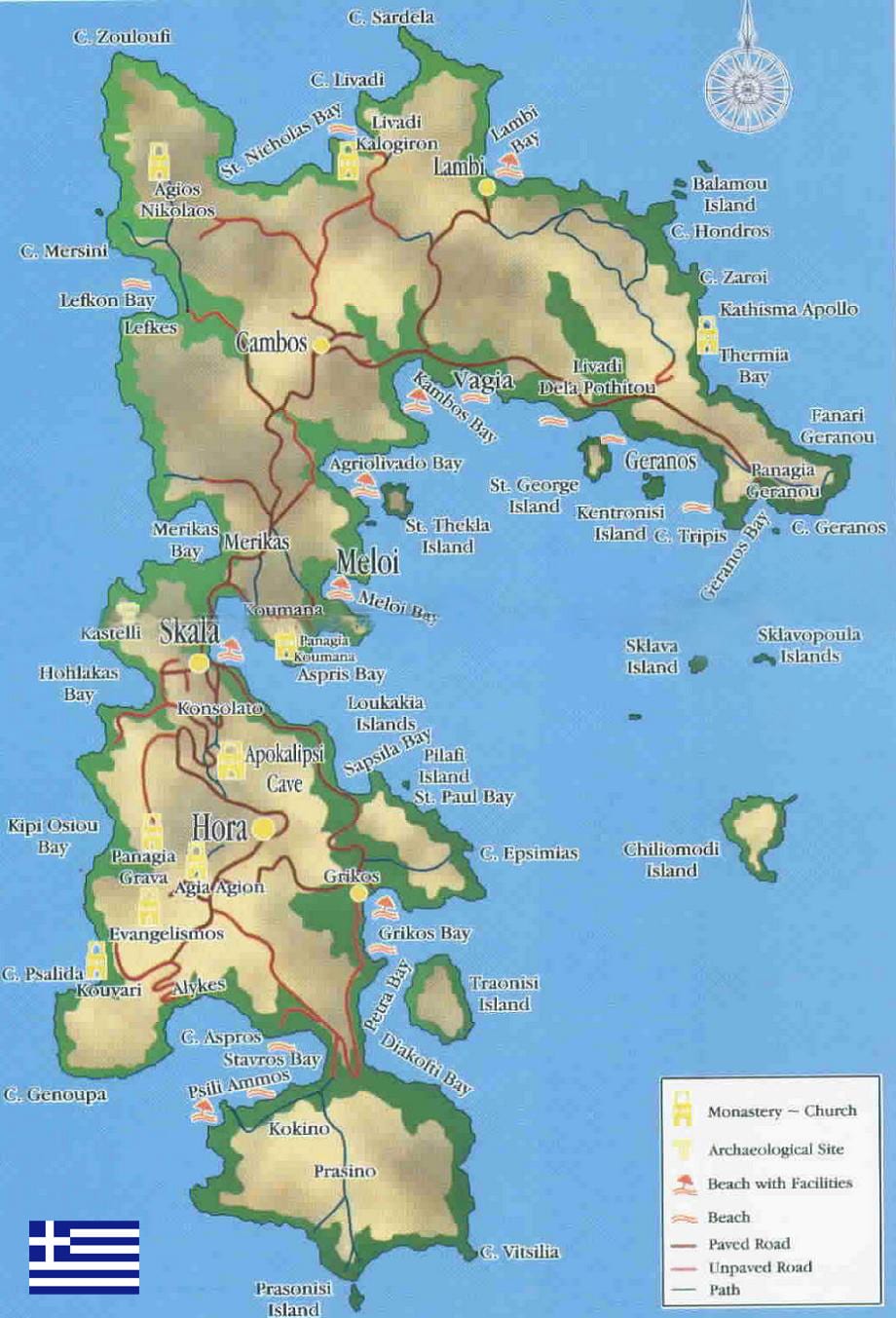

Skala is the only seaport on Patmos, a little seahorse-shaped island (only 13 square miles) in the southeastern Aegean. Much of the island has been designated as a UNESCO World Heritage Site, visited by pilgrims from all over the world who want to see the sacred place where St. John received his apocalyptic Revelation. In John’s day, Patmos was considered neither sacred nor a worthy tourist destination; rather, it served as a Roman penal colony, with none of the amenities enjoyed by the residents of Ephesus. By the last decade of the first century AD, Christianity had become an increasing threat to the official Roman cult of emperor-worship, and John, as probably the last living eyewitness of the resurrected Christ, had become a particular target of official persecution. According to legend, Domitian, whose rule had begun in 81 AD, decided to arrest John for sedition and subject him to a little test. The emperor ordered the preparation of a vat of boiling oil and commanded John to immerse his hands in it. If they got burned, then the apostle would be exposed as a fraud and would be executed. However, if by some miracle John’s hands remained unharmed, his life would be spared. Apparently the miracle occurred, and John was exiled to Patmos for the remainder of his life. His banishment ended before his death, however, because John was among the political prisoners pardoned by Domitian’s enemies after the emperor was assassinated. The evangelist had been on the island for about eighteen months. No one knows how old John was at the time of his release because no one knows exactly when he was born, but undoubtedly he was an old man. Tradition has it that he had become so frail that he had to be carried back to Ephesus on a litter.

Entrance to the Cave of the Apocalypse

We haven’t reached the point where we need to be transported by litter, but we did require a tender to get us onto Patmos this morning. There we were met by Nikolas, who would be the most animated, expressive guide we have had yet. The first place he took us was the Cave of the Apocalypse, located about halfway up a rocky promontory overlooking the harbor. This site, described as “the Mt. Sinai of Europe,” is where John is believed to have received the visions recorded in the Book of Revelation. The grotto is now enclosed within a small monastery complex, originally established there in 1088 to protect the sacred site.

View of Patmos from the Monastery

Listening to Nikolas as he reverently pointed out the stone where the apostle had laid his head, and then the niche that John used as a handhold when he rose, we could tell that Nikolas was completely devoted to his Greek Orthodox faith and what he described as its two pillars: the Holy Bible, and Tradition. Apparently, these are the two pillars of Patmos as well–although the latter authority seems to take precedence over the former. (We could see Jim almost literally biting his tongue to avoid offending our guide by contradicting assertions that did not square with scripture–at least as Latter-day Saints interpret it.) Nikolas explained that according to tradition, John had been accompanied to Patmos by Prochorus, one of the seven men mentioned in Acts 6:5 who were appointed to administer to the temporal needs of the early church. Prochorus is thought to have acted as John’s scribe, recording the Book of Revelation as the evangelist described what he saw in vision and helping him express it in Greek. (Nikolas also claimed that Prochorus was the author of the Acts of John, although most scholars believe that that apocryphal book was not written until late in the next century.)

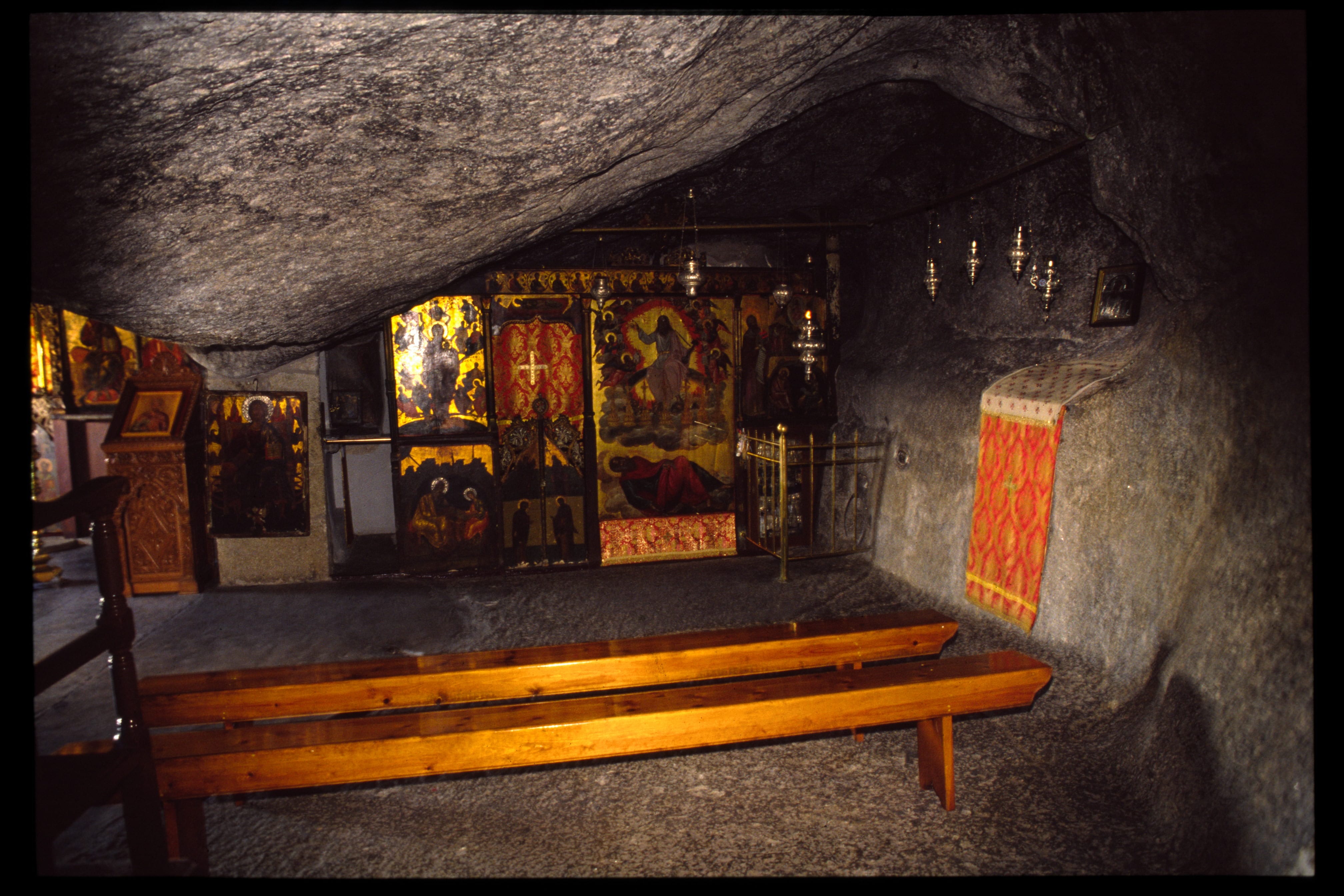

Cave of the Apocalypse

We were not allowed to take any photos inside the Cave of the Apocalypse, so we had to search the Internet to find one of the gold-encrusted, icon-decorated chapel. (Nancy hoped to snap a surreptitious photo of the custodial monks’ spartan washroom, which we passed in the hall just outside the grotto, but for some reason her camera would not cooperate.)

Monastery of St. John the Theologian

Nikolas, our guide, under the decorated arches of the monastery church

In the village of Chora at the top of the Patmos promontory is the current Monastery of St. John the Theologian, relocated there in the twelfth century because the site of the grotto was too exposed to the pirates who often pillaged the port. The monastery was significantly enlarged in 1738. Currently it houses about forty monks who belong to a cenobitic order, meaning that they emphasize communal living over a life of solitary devotion, functioning almost as a family. Each day (which begins at 2:30 a.m.) is divided into thirds: eight hours for spiritual study and worship, eight hours for chores, and eight hours for sleep.

Michael, Barry, and Eva listen to our guide as we wait for our turn to enter the church

The monastery’s church also is divided into three sections in the traditional Orthodox style, although the parts are not equally divided: the medium-size narthex at the back is open to all; the larger center nave is for congregants who have been baptized; and the small sanctuary, containing the altar and often hidden by a screen, may be entered only by a priest. Nikolas reminded us that, like the one in Solomon’s Temple, the altar of an Orthodox church always faces east. As we left the nave, he also pointed out some twelfth-century frescoes that had been plastered over during some redecorating in the seventeenth-century. The later paintings crumbled in a 1956 earthquake, revealing the long-hidden treasures.

A passageway within the monastery

Nancy sits among the bells on the roof of the monastery

Monastery courtyard

Museum-vestry of the Monastery of St. John the Theologian

Across the flower-filled courtyard from the chapel is the monastery’s museum, which contains a splendid collection of historic manuscripts, painted icons, golden censers, and richly embroidered vestments. While examining the exquisite work on an antique velvet cape, Nancy suddenly remembered the weaving process we had watched at the rug factory yesterday and realized that the fine silk nap of the velvet fabric probably required even more painstaking work than the embroidery.

Painting of Christ attributed to the young El Greco

One of the most intriguing pieces in the museum is a gilded sixteenth-century icon depicting Christ. The painting has been attributed to Doménikos Theotokópoulos, a native of Crete who eventually became famous in Spain as simply “The Greek”–El Greco. If this painting is indeed by El Greco,- it must have been done early in his career, before he began elongating his human figures.

This charming view can been seen from the window of the monastery’s W.C.

The Orthodox Church in Skala’s central square

The villages of Patmos resemble those on Mykonos, although the streets are not as labyrinthine. Nikolas explained that the lime-based whitewash slathered on most buildings helps to keep their interiors cool. (It also acts as an insect repellent, which is why we’ve seen so many whitewashed tree trunks.) Rooftops are made flat and watertight so residents can collect and reuse rainwater, which helps Patmos remain relatively self-sufficient year round. Most homes have their utility rooms on the lower floors; the upper floors, which provide more breezes as well as better views of the sea, are used for living quarters.

The sign of the Seahorse Emporium in Skala echoes the shape of the island

Patmos, an island shaped like a seahorse

After a brief return to the Wind Star for lunch (Michael especially enjoyed today’s hot special: salmon and spinach en croute; Nancy treated herself to yet another helping of bread pudding after she ate her salad), we took the tender back to Skala to find a café with free wifi. Jody came along with us, so she and Michael settled down at a patio table to work and browse the Internet while Nancy browsed through the shops nearby. Many of Skala’s boutiques had closed for the afternoon, however, so she went back to the café where she had left Michael and Jody, but they seemed to have disappeared. After a fruitless search around town–and asking every other member of the Gee Group that she met whether they had seen her husband–Nancy decided to go back to the Wind Star.

Wind Star “pool”

Ready to cool off after wandering around town in the heat of the afternoon, Nancy put on her swimsuit but soon discovered that the Wind Star’s ocean-swimming platform had just been drawn back onto the ship. Instead, she decided to take a dip in the onboard pool, which is so small that “taking a dip” is about the only action possible other than treading water. Moreover, Nancy discovered that the water is so salty that one really needs a thorough rinsing after taking a dip, so she decided that the experience was not worth repeating. She hurried through a shower so she wouldn’t miss a scheduled group meeting; Michael returned just as she was drying off.

“Where did you go?” she asked. “I looked all over town for you!”

“We stayed at the same café the whole time,” he replied, “but after you left, we moved inside where the reception was better.” (Nancy had peeked inside, but apparently not far enough into the right corner.)

The Gee Group had agreed to meet at 5:00 so we could discuss what we had heard and seen about St. John today and compare our findings with what we have learned from the scriptures. Although our faith in the validity John’s writings and his testimony of Christ does not depend upon seeing physical evidence, it has been inspiring to be here in Patmos and consider what John must have experienced nearly two thousand years ago.

Michael had to skip out before the discussion was over because he had signed up for the “Treatment for Men” offered at the Wind Star’s spa. Lucy, the Welsh masseuse, must have been bored, because what was supposed to be a 50-minute session turned into a 90-minute session that included a facial as well as a whole-body massage. The massage was wonderful, and the facial was, well, interesting. Michael says he would do the massage again but probably skip the facial–even though Lucy was pleased with how much more “refreshed” his skin looked afterward.

Jody, Michael, Steve, Jan, Cathy, Jeff, and Dyrk: our “candlelight” dinner companions

Caesar salad

Smoked buffalo

Mahi mahi

For tonight’s dinner, the Gees had reserved seating for our group on the aft deck next to the pool. This private, open-air venue is called Candles, and its menu includes grilled items that aren’t offered in the main dining room. Tables near the railing were already occupied by the time we arrived, so we were seated along with Steve, Jan, Cathy, Jeff, Jody, and Dyrk at a long table in the passage next to the bar. From there, it was difficult to enjoy the view, but when the wind picked up as we sailed away from Patmos, we were grateful to be in the most sheltered area on deck. (Nancy also was glad that she had worn long johns under her maxi dress and brought a down jacket.) Each person chose an appetizer (Caesar salad for Michael and some marvelous, thinly sliced smoked buffalo with arugula for Nancy) and then a grilled meat (Michael and Nancy shared mahi mahi and sea bass with each other). Assorted sides (potatoes au gratin, rice pilaf, grilled mushrooms, and asparagus) were served family-style. For dessert we both enjoyed the crème brulée. We also enjoyed getting better acquainted with Steve and Jan, who are serving as leaders of a special church unit for young, single adults, just as we had done a few years ago.

Normally we would have lingered at the table, continuing to talk long after the empty dishes were cleared away, but tonight we all moved into the lounge so we could get seats for the crew talent show (and to get out of the wind). We didn’t have high expectations for “Wind Star’s Got Talent,” but we were pleasantly surprised. James, our cruise director, acted as emcee; the boyish Brit further endeared himself to us with a series of terrible puns based on names from Greek mythology (“How do Greek women get ready for a toga party? With a Hera appointment, of course”). Saka, our own stateroom steward, was the first to perform; he quickly conquered some initial bashfulness to demonstrate a voice that was unpolished but quite nice. “Bashful” does not apply to Yusuf, the charismatic proprietor of “Yusuf Kingdom” in the AmphorA dining room, who rollicked through a Julio Iglesias hit despite a caveat that “it’s in Spanish–I have no idea what the words mean!” The housekeeping crew did a comedy/dance routine with mops and vacuums, and the five females on staff collaborated on a hip-hop dance number, but for us the highlight was a traditional Indonesian dance performed by two cooks, outfitted in full native costume.

Traditional Indonesian dance

The Wind Star’s crew comprises about a hundred workers, most from Indonesia and the Philippines. A handful–mostly administrative staff–are from Europe (including the Polish captain), and the head chef is from India. The hotel manager probably is from one of the Caribbean islands, but we haven’t determined where; otherwise, it seems that the only North Americans on board are the passengers. Depending on their level, crew members are at sea anywhere from four to nine months, then have two or three months off. Saka told us that he had started his current contract with a series of five ten-day Caribbean cruises, then spent two weeks crossing the Atlantic (with crew only, no passengers), followed by five rounds of ports in Spain and Portugal. Ours is the first of five Aegean cruises, then he will head to northern Europe to finish out his contract. After that, he will finally have a chance to go back to Indonesia. After three months at home, he’ll be back at sea. Not a life either of us would choose, but Saka, Yusuf, and all the other crew members we talked with seem to love their work–and their commitment shows. They have kept the Wind Star spotlessly shipshape and have cheerfully, conscientiously attended to all our needs as passengers.

Leave A Comment