Flag of Turkey

On our way to breakfast this morning, the first thing we saw when we opened the outside door at the top of the stairs was a gigantic red flag waving over the cruise terminal. “Oh my gosh,” thought Nancy. “We are in Turkey!”

Ataturk

To be precise, we are in Kuşadasi (pronounced ku-SHAH-dah-sih), which is presided over by a huge, hilltop statue of Ataturk, the army general who led the Turks to independence in 1919 and then became the republic’s first president. Ataturk is revered by his people for having propelled the Muslim-majority country into the modern world by establishing a secular government and a relatively stable economy. The current president seems to be less revered than feared. In a national referendum held only a few weeks ago, Turks approved a constitutional amendment allowing Recip Tayyip Erdogan unprecedented, near-dictatorial powers, and many are concerned that he may be moving the republic away from secularism and more toward something like an Islamic state. As a result of this mounting uncertainty—as well as its proximity to war-ravaged Syria–many western tourists have decided to avoid visiting Turkey. Carol says that three or four cruise ships that should have been moored in Kuşadasi’s harbor today are missing. That’s a pity for the thousands of passengers who won’t get to visit this exotic port–but all the better for us.

Kuşadasi, which means “bird island,” is named for the little island in its harbor that is populated mostly by pigeons

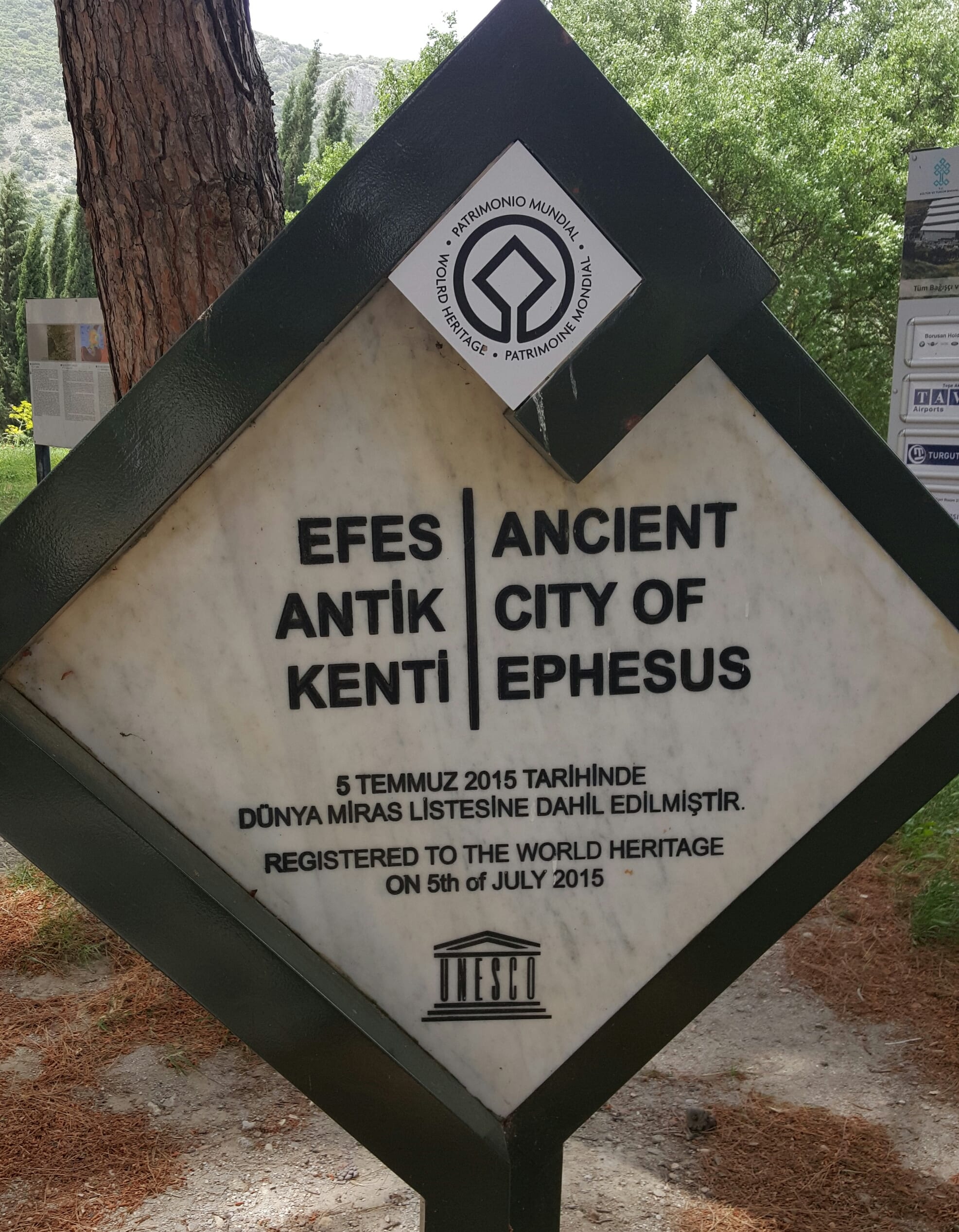

Exploration of Kuşadasi (beyond the maze of chichi boutiques that disembarking passengers must thread their way through to get out of the cruise terminal) would have to wait until later, because our primary destination for the day was Ephesus, known as “one of the greatest outdoor museums in the world.” After we boarded the bus, Melih, our Turkish guide, amused us as much with his pronunciation of English (“The first site we will wisit this morning is the last home of the Wirgin Mary”) as with his philosophical commentary (“We will walk a long way today. It may get wery hot, and there is wery little shade, but in order to appreciate what is beautiful, you should suffer.”)

On the road toward Ephesus, Melih explained that the acres of level land on either side of the highway we were traversing are useless for agriculture because the soil is too salty. In ancient times, this land had been the harbor of Ephesus, but centuries of silt washing into the mouth of the Cayster River pushed the Aegean farther and farther away. Even in Ephesus’s heyday, the harbor had to be dredged periodically; finally, the task became too onerous, and by the sixth century AD the great city had been abandoned. Its ruins now lie about four miles from the sea.

St. John’s wort

As the road began to climb into the hills, Melih drew our attention to the vegetation: the pine trees that lend a distinctive flavor to the local honey, mulberry trees that support an important silk industry, and abundant St. John’s wort: a large shrub with bright yellow blossoms that is used–problematically–as an antidepressive. (It’s called St. John’s wort not because the saint is supposed to have any particular power to relieve mental disorders, but because the plant blooms around his day on the Christian calendar.)

Our group lines up to enter the House of Virgin Mary

This structure, which looks curiously like an ancient baptismal font, is in a courtyard near Mary’s house in Selçuk

Before getting to Ephesus, we stopped briefly in the “willage” of Selçuk on Mt. Koressos to “wisit” what tradition claims was the final home of Mary, mother of Jesus, before her assumption into heaven. As he hung on the cross, Jesus had charged St. John with caring for his mother, and the gospel of John records that “from that hour the disciple took her unto his own home.” It seems reasonable to assume, then, that if Mary were still alive when it became necessary for John to leave Jerusalem permanently, she would have gone with him. There is evidence that John went to preach in what the Bible calls “Asia”–modern Turkey–and spent considerable time in Ephesus. A long tradition holds that Mary ended her tenure on earth in this region as well.

Some worshippers petition favors from the Virgin by lighting candles …

…while others leave prayers written on rags or scraps of tissue paper

In the nineteenth century, a German nun known as Blessed Anne Catherine Emmerich claimed to see Mary in a vision, and then identified this house in the town of Selçuk, a few miles from Ephesus, as her final residence. Though the authenticity of Catherine’s story has been ratified by neither the Roman Catholic nor the Orthodox Church, this shrine has been visited by the faithful for over 125 years, and has received blessings from several popes, most recently from Benedict XVI in 2006. We were not allowed to take photos inside the building; if we had, we would have tried to capture the sight of an elderly worshiper wearing a long, old-fashioned dress and a beautiful veil of antique lace over her head, reading scriptures from her smartphone.

Fountains of holy water

Visitors to Mary’s shrine may be blessed with love, long life, or wealth–depending on which fountain of holy water they choose to drink from. To speed things along when pilgrims arrive in large groups, the Turkish Ministry of Culture built a fourth fountain nearby that supposedly combines the benefits of the other three.

From Selçuk, it was only a short drive to the upper entrance of Ephesus. There is no modern city here, only a complex of ruins–but what a complex! The site is nearly as extensive as Colonial Williamsburg or Old Nauvoo, except there aren’t any costumed docents or re-enactors who show you how horseshoes were made in centuries past.

From Selçuk, it was only a short drive to the upper entrance of Ephesus. There is no modern city here, only a complex of ruins–but what a complex! The site is nearly as extensive as Colonial Williamsburg or Old Nauvoo, except there aren’t any costumed docents or re-enactors who show you how horseshoes were made in centuries past.

Because the main street running through the middle of Ephesus is on a slope, most of its paving stones have ridges carved into them to prevent pedestrians and horses from slipping. The distance from the upper entrance to the lower entrance is about 1.5 miles

Holes in the main water lines show where secondary pipes connected to the municipal system; the size of the hole determined how much each user would be charged for the service

First settled around 1100 BC, Ephesus had become the fourth largest city in the Roman Empire by the time Christian missionaries began arriving, with a peak population of about 250,000. The city boasted the latest in modern conveniences during the mid-first century because the Romans had completely rebuilt the vital commercial center following a massive earthquake in 17 AD. Besides well-paved roads and impressive monuments, master engineers installed a sophisticated system of clay pipes that supplied clean, running water to private homes as well as public fountains, and also flushed out the city’s latrines.

The ancient Romans loved to socialize. Even public toilets were designed to facilitate conversation while people took care of personal business

Melih told us that in cold weather, Roman citizens sent slaves ahead of them to warm up the seats in the latrine. He also explained that instead of toilet paper or disposable wipes, the ancients used sponges soaked in vinegar to clean their nether parts, and he pointed out the trough where the sponges were kept. They were tied to sticks to make them easier to reach from the toilet. After sharing this information, Melih reminded us of what the Roman soldiers had given to Christ when he hung on the cross and said, “I thirst.” The vinegar-soaked sponge likely came from a public latrine, and was yet another means of humiliating the dying Savior.

This symbol, scratched into the rock pathway, incorporates the letters of the Greek word for fish: ΙΧΦΥΕ. Both the symbol and the word became covert signs of Christianity because the letters form an acronym for words that translate as “Jesus Christ Son of God Savior”

Ephesus would remain an important nexus of trade and learning during the first centuries of the Christian era. The city played a critical role in the growth of the fledgling church. Paul spent a fair amount of time here and had significant success, nurturing a community of believers that would persist until the city itself fell into decline. In 341 AD, Ephesus hosted a historic Christian council where leading theologians discussed the divinity of Jesus Christ. The hotly contentious debate drove another wedge between the western branches of the church (which supported the idea that Mary was the mother of God) and the eastern branches (which preferred to think of Mary as the mother only of God’s human manifestation). During our visit, we saw little direct evidence of Christian influence–no crosses or Byzantine-era churches–but we knew that the Way of Christ had had a definite impact on the city.

The primary object of worship in ancient Ephesus was Artemis (known in Latin as Diana), goddess of the moon and of the hunt. Her great temple, located on a hilltop outside the city, was renowned as one of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World. Even more than the Temple of Aphrodite in Corinth, the richly decorated Temple of Artemis in Ephesus drew pilgrims from all over the civilized world, and local artisans made a good living selling small souvenir reproductions of the temple’s famous statue of the moon goddess. Sadly, the same qualities that made the temple an attractive tourist destination also made it an irresistible object of plunder for conquerors and thieves; as a consequence, nearly all of its extant artifacts are found not in Ephesus but in foreign museums. Today, so little of the once magnificent temple remains at the site that we didn’t even visit it–but we did have cause to remember it. Acts 19 describes a riot that occurred when the silversmiths of Ephesus protested that by preaching against their patron goddess, Paul and his followers were undermining not only their business but the welfare of the whole city. (Jim told us that he owns a Roman coin from this era, inscribed “Great is Diana of the Ephesians”–apparently minted in response to the Christians’ growing influence in the empire.) As a result of the uproar, Paul had to make a quick getaway to Macedonia.

Prytaneion

The upper part of Ephesus, where we began our tour, was reserved for civic buildings such as the Prytaneion, a complex that includes an official reception hall as well as a temple dedicated to Hestia (aka Vesta), goddess of the hearth and fertility. (Melih explained that the famous Vestal Virgins charged with keeping the Prytaneion’s sacred hearth alight met only the Greco-Roman definition of virgin: a woman who had never given birth.) The nearby Temple of Osiris, an Egyptian deity who was believed to hold the powers of resurrection and final judgment, had been erected by Roman officials who–according to Melih–hoped that the similarities between the stories of Osiris and Christ would lure Jesus’s troublesome followers to join the pagans there instead of worshiping in their own peculiar ways. Paul and other Christian evangelists frequently had to warn their disciples to abstain from eating meat from animals that had been sacrificed to idols, and to avoid participating in the revels that accompanied the ensuing public feasts.

Amazons

Depictions of the female warriors known as Amazons are popular in Ephesus. Melih told us that their name is derived from the Greek for “without breasts” because, supposedly, Amazon archers cut off one breast to achieve better aim. This etymology has been discredited by scholars–but it does make a good story.

Civic agora

Temple of Domitian

Other buildings clustered around the civic agora in the upper part of town include imposing monuments to Roman heroes and emperors–who, since the death of Julius Caesar, were officially considered gods. Domitian, who ruled Rome from 81 to 96 AD, was the first emperor to have a temple erected in his honor in Ephesus. Domitian was popular with the people because he reigned during a time of relative peace and prosperity, but he was also known to be paranoid and vindictive. It was probably he who banished John to the Isle of Patmos for promoting seditious Christian ideas. And Domitian became so unpopular with his own government that he was finally assassinated by a coalition of senators. Subsequently, Domitian’s name and image were stricken from many official monuments–despite having been literally carved in stone.

The odeon in Ephesus served as a hall for senatorial debates by day and musical concerts by night

Nike, goddess of victory

The rod of Asclepius

The rod of Asclepius, which features one snake entwined around a staff, marks the location of a temple where the infirm could bring offerings to the god of healing. For the ancients, snakes–who regularly shed their skins–symbolized renewal. Jews and Christians see in the rod of Asclepius an association with the brass serpent Moses attached to a rod and raised to heal wounded Israelites; medical practitioners have used this symbol for centuries. It is often confused with the caduceus, symbol of the messenger god Hermes (aka Mercury), which is topped by a pair of wings and two snakes–characteristics associated with speed, commerce, eloquence, and trickery.

Herakles Gate

Judith stands at one of the stairways that constitute side streets; they lead to private residences built in terraces on the hillside

The Herakles Gate marks the transition between the civic section of the city and the lower commercial district. A large fountain nearby served not only to provide clean water for the plebeians who couldn’t afford homes with indoor plumbing, but also as a gathering place where people could meet and gossip with their friends. (According to Melih, the merchants of Ephesus observed an afternoon break from noon until 6 p.m., but although the Ephesians might have included a nap, they spent most of the time socializing.) The fountain is dedicated to Trajan, a military hero known as one of the “five good emperors” of Rome.

Trajan’s Fountain

Hadrian’s Monument

Although most of the figure of Trajan is now missing from his fountain, the remains confirm that the ancient Romans knew the earth was round, not flat, as medieval Christians would claim. A round globe lies next to his left leg, and the inscription translates as: “The world is under my foot.”

A monument to Hadrian, another one of the five good emperors, can be seen farther along Curetes Street, the main thoroughfare through the commercial district. It is decorated with figures of Nike and Medusa, as well as friezes depicting the founding of Ephesus. These sculptures, like many on display in open-air venues, are reproductions; originals are housed elsewhere in climate-controlled museums.

Barrel-vaulted treasury

Probably the most fascinating ruins of Ephesus are protected within a large modern structure that allows visitors to watch the ongoing excavation of several terrace houses. These homes were built during the fourth and fifth centuries AD, but have been uncovered only in the last thirty years.

A small room cooled by running water was used for food storage

We’re not talking about humble studio apartments here, but a complex of huge townhomes, complete with barrel-vaulted treasuries and impressive courts for transacting business, in addition to elegant dining and entertainment halls, libraries, and bedrooms. Surprisingly, kitchens were rare; Melih reminded us that ovens and open stoves create not only unpleasant heat but also danger, so most cooking was done in separate commercial kitchens. Servants would go out to purchase prepared food and then bring it home for plating and presentation. Luxury homes included indoor plumbing, but such facilities usually were shared by the several households in a single building–and most people preferred to use communal baths for social purposes, anyway. Lead water pipes running through the buildings helped to keep them cool in summer and warm in winter–but undoubtedly also poisoned the wealthy residents who drank from them. (Lead poisoning is thought to be a significant contributor to the decline and fall of the Roman Empire.)

A wall covered with marble veneer

Silk cords and wedges of wet wood were employed to produce the thin slices of marble required for the veneers that cover many walls in the terrace-home complex. It was a labor-intensive, expensive process; therefore, marble was used primarily in the reception and entertainment halls on the lower levels to impress visitors. Archaeologists are still painstakingly piecing together this gigantic puzzle–with no convenient box-top picture to guide them.

Lovemaking chamber

Library

Frescoes, which were less expensive to produce than marble veneer, decorated the private living areas on upper floors. Their subjects help archaeologists identify the probable use of many rooms. Well-preserved depictions of Eros and Aphrodite in a small interior chamber suggest a place for lovemaking; Athena and Socrates flanking a shelf within a niche probably indicate a library.

A fine mosaic depicting Poseidon, guardian of the seas, decorates the floor of a grand entrance hall in what was likely the home of a shipping magnate.

Mosaic of Poseidon

At the foot of Curetes Street is the Celsus Library, a magnificent structure commissioned by the son of a popular, influential Greek who became a Roman consul. Completed in 117 AD, its collection was exceeded in size only by the libraries of Alexandria and Pergamum. Unfortunately, the entire collection–as well as the interior of the building–was destroyed by a fire in 262 AD. The remains of the building eventually were transformed into a nymphaion (a monument to nymphs that included a fountain). The imposing façade continued standing for nearly a thousand years until an earthquake finally brought it down. During the 1970s, archaeologists managed to reconstruct two of the façade’s original three stories from the rubble; sixty percent of the material in the current structure is original.

The entire Gee Group assembled in front of the Celsus Library: Jan, Steve, Budge, Linda, Jeff M, Pattie, Eva, Amanda, Barry, Joyce, Carol, Judith (kneeling), Jim, Michael, Nancy, Mark, Lynn, Keith (kneeling), Richard, Nan, Cathy, Dyrk, Jody, and Jeff J

Sophia

Arete

The four figures on the Celsus Library’s façade represent Sophia (wisdom), Arete (virtue), Ennoia (intelligence) and Episteme (knowledge).

Neither Melih nor Jim could point out the exact location of the School of Tyrannus, where Paul had taught after he was banned from the Jewish synagogue, or that of the synagogue itself. It’s likely, however, that they were somewhere in the vicinity of the library (which had been built after Paul’s sojourn in Ephesus), which is near the lower agora.

Ennoia

Episteme

Today, the agora that once was the city’s bustling marketplace is now a quiet lawn. We found a shady spot where the whole Gee Group could gather for our second devotional, this one led by Judith and Richard. They shared reflections on Paul’s counsel to the saints of Ephesus to “keep the unity of the Spirit in the bond of peace.” Remember, he said: “There is one body, and one Spirit. … one Lord, one faith, one baptism, one God and Father of all” (Ephesians 4:3-6).

Melih listens while Judith shares her devotional message

On the other side of the agora from the Celsus Library is the largest Greco-Roman amphitheater in Asia Minor, with an audience capacity of 25,000. In antiquity, the amphitheater was used not only for theatrical and musical performances, but also for gladiatorial contests and public debates. (It was here that the silversmiths held their demonstration against Paul in the first century AD.) Since restoration efforts began in Ephesus during the 1970s, the amphitheater has once again been put to use as a concert venue, with performers as diverse as Joan Baez, Sting, Elton John, and Luciano Pavarotti taking the stage. However, after reverberations from electronic amplifiers damaged the ancient structure, only acoustic concerts have been permitted since 2002. And really, the natural acoustics are such that no electronic amplification is necessary. Nancy proved the point by immediately responding to Eva’s suggestion that someone should sing. The first song that came to her mind was “A Mighty Fortress is Our God,” and the sound of one voice suddenly filling the theater startled even those who had climbed to the back rows, far above the stage.

Greco-Roman amphitheater

Turkish merchants obviously have a sense of humor

As echoes of the hymn died away, we left the amphitheater, picked our way past hordes of aggressive souvenir vendors, and once again boarded the bus. Cathy and Eva passed around packages of the candies they had bought so that everyone could sample various flavors of Turkish Delight (which tastes much like Aplets and Cotlets).

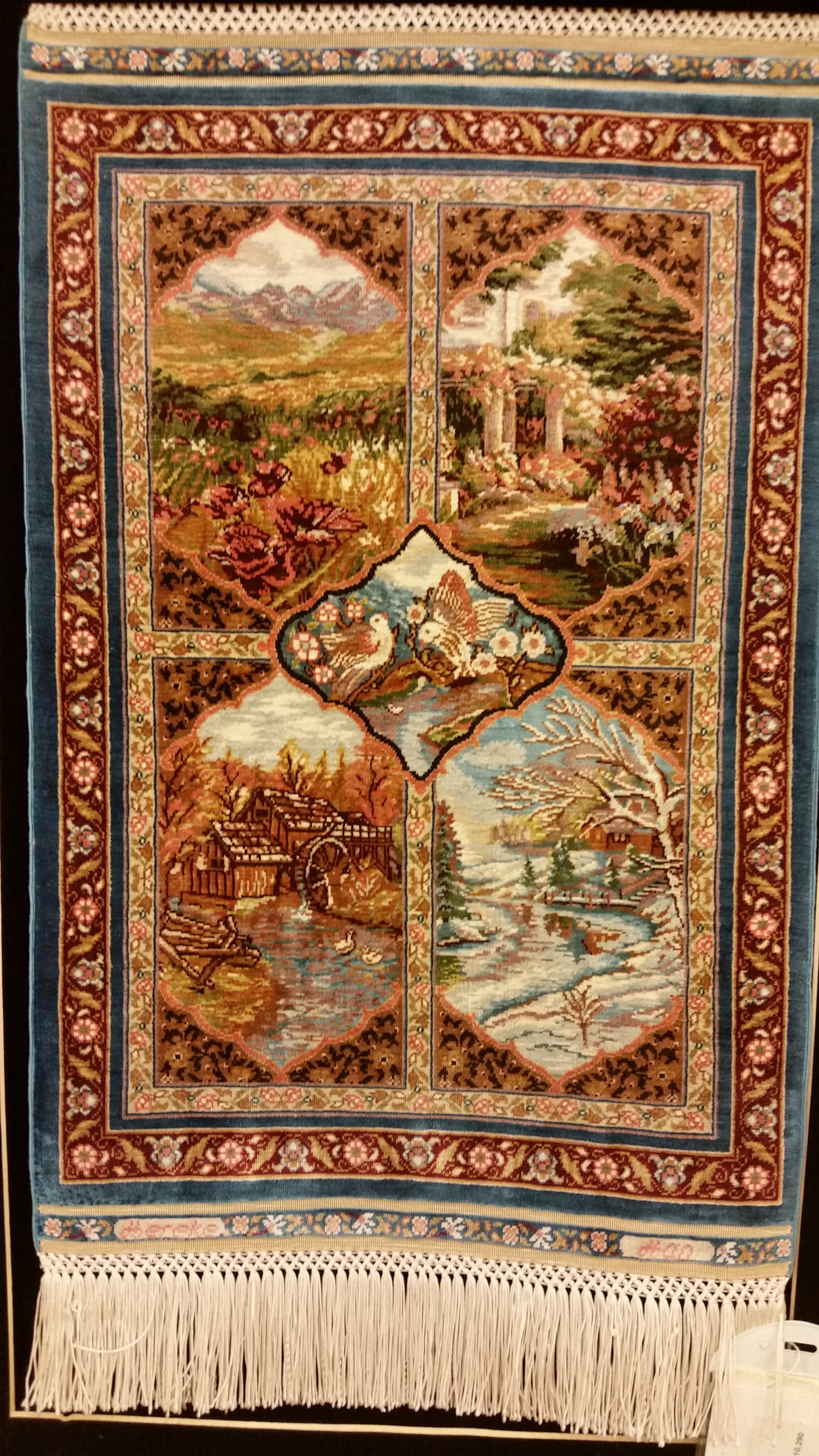

Carpet weavers

On the way back to Kuşadasi, we stopped at a rug factory where we watched a couple of young weavers demonstrate their craft. We were fascinated by their dexterity as they handled hundreds of strands in dozens of colors, tying multiple knots per minute to create intricate patterns. Factory guides also showed us how the filaments from a silkworm’s cocoon are carefully unwound and spun into thread. We learned that a single strand of silk thread suitable for rug-making requires 400 separate filaments, and that such a thread is virtually unbreakable.

Extracting the filaments from the cocoons

After the demonstration, our group was ushered into a showroom where a host of pitchmen waited to entice us to buy a rug. So we could better admire the variety of designs and colors available, a crew of assistants dramatically rolled out carpet after carpet, sometimes taking the smaller ones and twirling them overhead like pizza dough. So we could better appreciate the differences in density and fiber content (wool, cotton, silk, or various combinations) we were encouraged to take off our shoes and walk over the rugs with bare feet. Even without the barefoot test, it was easy to see that a rug with 600 knots per square inch was clearly superior to one with the 120 knots per square inch (standard for an average-quality rug).

Rug or work of art?

The clever salesmen gradually separated each couple who expressed any interest at all in making a purchase from the rest of the group, leading them into separate rooms (carefully, almost literally by a silken thread) where they could exert all their persuasive powers. By the time we (Michael and Nancy) were able to extricate ourselves, our bus had already left! To our relief, Melih appeared to assure us that the bus was just turning around, and escorted us across the busy highway so we could board from the other side when it returned. A few minutes later, Jeff and Cathy came running out of the showroom and waved us down. They, too, had been separated from the group by the salesmen, but unlike us, they had actually bought a rug. It was not exactly an impulse buy because they are getting ready to furnish a new home and found a carpet they really liked, but they did experience a little buyers’ remorse for having made an expensive purchase under some duress.

Nan, Carol, Linda, and Budge listen patiently to a detailed presentation at the rug factory

Barry and Eva sit in front of a rug that combines traditional patterns with a modern geometric design

It was nearly 3:00 p.m. by the time we got back to the Wind Star. The lunch buffet at Veranda had closed, so most of our group ordered from the room-service menu and asked the steward to deliver to tables on the lower deck. (From the limited menu selection, we chose a Cobb salad, spinach and artichoke dip, and a burger.) Sitting in the shade and soaking in the beautiful scenery, we could reflect on the extraordinary experience of visiting Ephesus. Both of us felt much as we had after visiting Petra in 2015: awe for what peoples of the past had created and left for us to learn from.

One of the relatively empty shopping streets of Kuşadasi

Local fish market

After our late lunch, we headed back into town to do some shopping. Although Kuşadasi is hundreds of miles from Turkey’s borders with Syria, Iraq, Iran, and other regions in turmoil, its tourism industry has really taken a hit. Many of the cruise ships that haven’t simply struck Kuşadasi from their itineraries stop just long enough for passengers to make a quick trip to Ephesus and then steam away–which was the case with the two other ships moored alongside the Wind Star today. Local merchants and restauranteurs have suffered, and thus were very eager for customers.

Vegetable vendor

Nancy was just as eager to exercise the haggling skills she picked up from her mother, who had been an expert at getting rock-bottom prices from clothing vendors in the Los Angeles garment district. Nancy bargained the cost of some attractive silk scarves down to sixty percent of the original asking price but, mindful of the undoubtedly underpaid women who spend their lives spinning miles of silk filaments into thread, decided to stop there.

The imposing sixteenth-century caravanserai of Kuşadasi is now a hotel

A statue near the old caravanserai honors Okuz Kara Mehmed Pasha, who served as Grand Vizier to two Ottoman sultans during the 1500s and was responsible for turning Kuşadasi into a thriving port

Michael was interested in buying a wooden flute, but quickly learned that when no one could show him one worth adding to his collection, he had to simply ignore their entreaties and walk away. We must say, however, that although shopping in such an atmosphere can be trying, the Turkish vendors we met were unfailingly courteous and friendly–even entertaining.

After leaving the bazaar, we might have continued strolling down to the beach had we not needed to get back to the ship to change for our “Destination Discovery” dinner. Tonight, the Gee Group joined all the other Wind Star passengers on buses that would take us back to the ruins of Ephesus. We took a slightly different route this evening, which allowed us to glimpse what we had missed earlier: Kuşadasi’s lovely and largely empty beachfront. The guide on our bus (who drilled us in the correct pronunciation of Ku-SHAH-dah-sih) also pointed out the same stork’s nest atop a cell phone tower that Nancy had spied on this morning’s journey. We might have enjoyed the ride more had we not been sitting directly in front of a very loud and already inebriated woman—the same one whose friends had to practically carry her out of the dining room last night. We made sure to keep our distance from her during the remainder of the evening.

The Windstar “Destination Discovery” Event

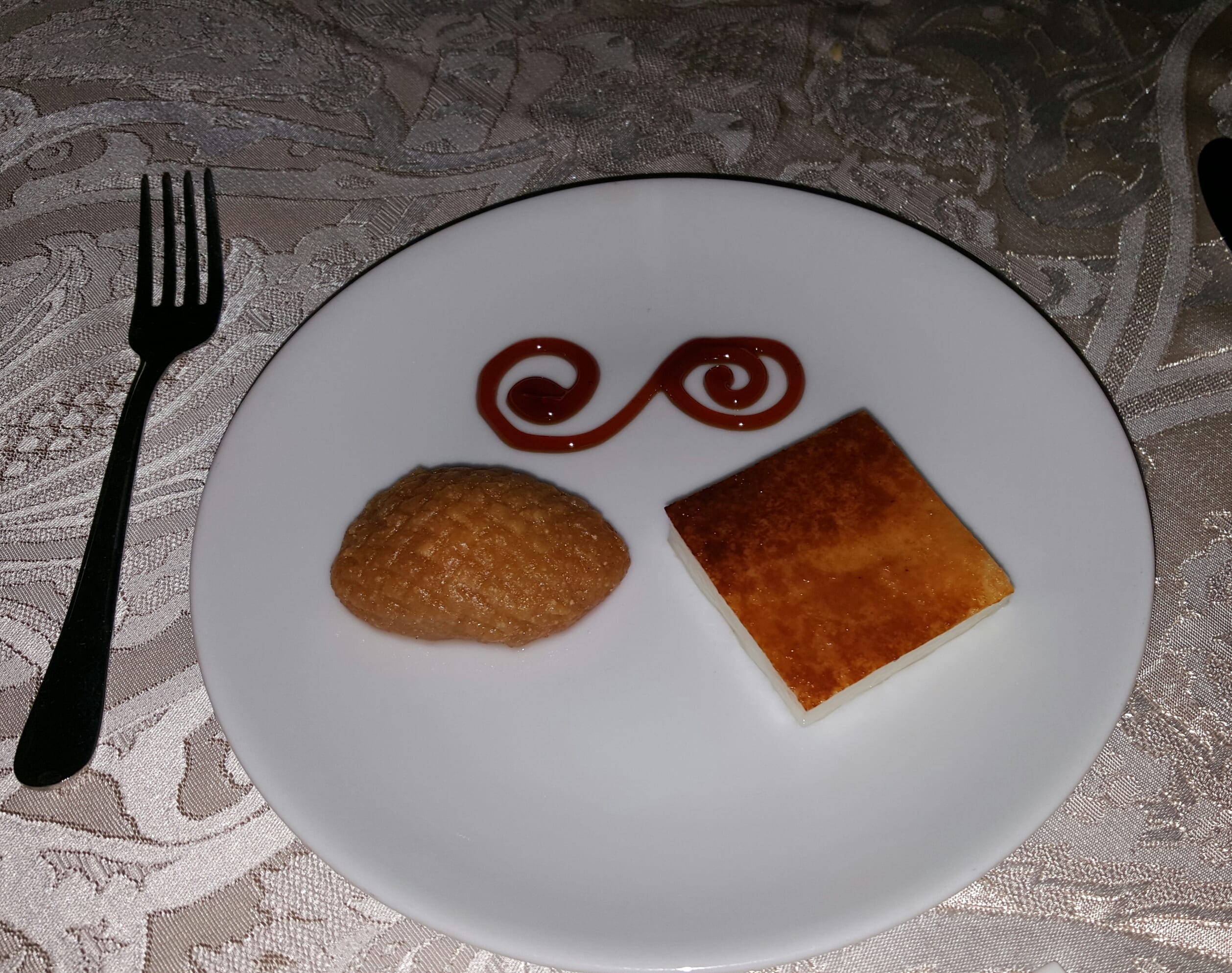

The buses unloaded where we had ended this morning’s visit, at the lower entrance near the amphitheater, and from there we were escorted up a candlelit path to the courtyard in front of the Celsus Library, where Windstar Cruises had arranged to host a private, formal dinner. The 148 of us were seated at elegantly draped round tables set with fine china, crystal, and silver, while waiters circulated with drinks (Peach nectar? Yes, please!) and a variety of mildly exotic hors d’oeuvres: lamb-stuffed grape leaves, eggplant in lemon sauce, tiny green beans and pimientos in olive oil, and thick, creamy yogurt mixed with chopped purslane. The hot appetizer was a pastry filled with vegetables and cheese, served with tomato sauce–the Turkish version of a spring roll. The main plate featured veal stew on a bed of puréed spinach (an odd combination, but tasty), accompanied by bulgur rice, a broccoli floret, and a slice of steamed carrot. The dessert plate included two unnamed Turkish specialties: one a square of flan, and the other a moist, spicy cake. A tux-clad string trio, sampling from the entire history of western music from J.S. Bach to Scott Joplin, serenaded us throughout the magical evening.

Exotic hors d’oeuvres

String trio

Barry, Eva, Keith, Nan, Richard, Judith, Mark, and Lynn (not pictured) were our tablemates for a magical dinner in ancient Ephesus

Hot appetizer

Main plate

Windstar Cruises must have made some special offerings to Artemis this week, because tonight she pulled a gorgeous full moon into the sky over Ephesus right on cue

Dessert

Accent lights made the library façade look even more dramatic after the sun went down

On our way back to the buses, we again passed the amphitheater, gloriously lit–artificially and naturally

When we returned to the Wind Star about 10:00 p.m., the crew had lined up in front of the gangway–Downton Abbey-style–to welcome us back to our floating home. Everyone agreed that even if our trip had to end right now, we could return to the States thoroughly satisfied–but we still have nearly a week of adventures to look forward to!

Steward ingenuity

When we got back to our stateroom, we found a cobra (crafted from a bath towel) coiled on top of our turned-down bed. What will Saka surprise us with next?

Leave A Comment