Masada (aerial view courtesy of Wikipedia)

This morning when we left the Golden Walls Hotel, we loaded all our bags onto the bus and said farewell to Jerusalem. Today’s first destination was Masada, another UNESCO World Heritage Site. The name is derived from the Hebrew word for fortress, and that’s what this is: a massive fortification built on top of a rock on the eastern edge of the Judean desert, overlooking the Dead Sea. The cliffs around the fortress drop about 300 feet on the west side and about 1300 feet on the east; three steep, narrow, winding paths lead from the desert floor up to the fortified gates. For miles and miles, Masada is surrounded by nothing but rock, sand, and a body of water that nothing can live in and no one can drink. So what is this fortress meant to protect?

Samir, our guide through Israel

To answer this question, we need to learn more about Herod the Great, the man who rebuilt Jerusalem’s Temple Mount in the first century BC. Herod was the son of a high-ranking Jewish official and a Nabataean mother. Having curried favor with the Roman-backed Jewish rulers, he was appointed governor of Galilee at age 25. By age 30, he had managed to convince the Roman Senate to name him King of the Jews, which meant that even though he wasn’t completely in charge of the territory of Palestine, he did have authority over just about anyone who wasn’t a Roman citizen. Since this position was not completely uncontested, Herod had to watch his back, so he decided to build a safe retreat for himself on this isolated plateau near the Dead Sea.

Army barracks

The complex includes an army barracks for more than five hundred men, stables for their mounts, and two luxurious palaces: a private one for Herod, and another where he could host guests in style.

Public immersion pool

Raised-floor steam bath

Bath

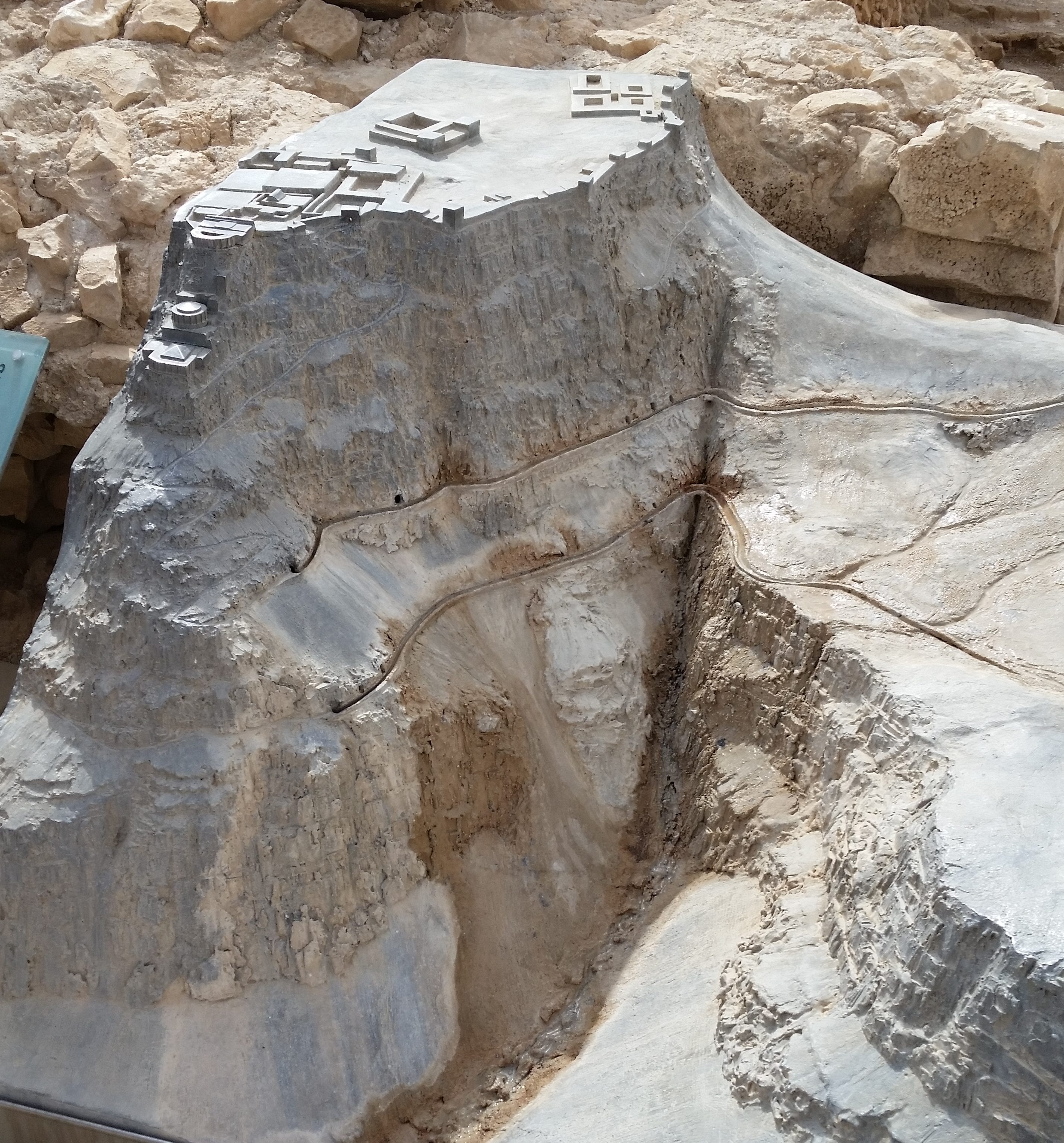

Model of water system

Visitors probably loved coming here, where they could relax and enjoy the swimming pools, Roman-style steam baths, and plentiful

sunshine. Herod must have paid attention to the water conduits and cisterns of Petra (where he probably spent much of his childhood), because he built a similar system at Masada to make sure his men would never go thirsty.

Cistern for the palace

65 stairs down to the cistern floor

1,000,00 gallon cistern

Grainary

Dovecote

A large grainary and two dovecotes attest that no one would go hungry, either, even if the fortress were besieged.

Receiving room in the Palace

View down to lower palace

Stairs to the palace

Living chambers between casement walls

Construction was conducted in phases from 35-15 BC. During the final phase, the complex was almost entirely enclosed by a casemate wall: a double wall with about eight feet between the inner and outer layers that not only provided extra defense, but also could be used as living chambers for soldiers and servants, or extra storage space.

Remains of one of the 8 Roman camps surrounding Masada

The siege ramp

Herod died shortly after the birth of Christ, but Masada continued to be used by the Roman army until 66 AD, when the Sicarii, a group of Jewish rebels associated with the Zealots, managed to capture the fortress. When the temple in Jerusalem was destroyed in 70 AD, more Sicarii fled to Masada; eventually, nearly a thousand rebels sought refuge there. The Roman governor laid siege, surrounding Masada with 15,000 troops, but the rebels were better protected and better supplied than the army. They held out for three years, until the Romans completed contruction of an attack ramp up the west side of the plateau.

Initially, the rebels on top of the fortress we able to impede work on the ramp by throwing stones at the soldiers who were building it, but then the Romans replaced their soliders with Jewish POWs from elsewhere in conquered Judea. The rebels chose not to kill their fellow Jews, even though they realized that loyalty to their own brought the inevitable end that much closer. They watched as the Romans constructed a giant siege tower and then slowly pushed it up the completed ramp.

Replicas of the “lots”

According to Josephus (the first-century Jewish historian who lived through the rebellion in Jerusalem but eventually switched his allegiance to Rome), when Roman troops rammed through Masada’s wall and entered the fortress, the buildings were in flames and the rebels were already dead. Resolving to maintain their own dignity and prevent their families from being tortured, the Sicarii had killed their wives and children, set the buildings on fire, and then drew lots to determine which of them would kill the remaining men and before committing suicide. Two women and a few children were found alive to tell the tale. Jim told us that archaeologists who excavated the site in the 1960s found ten potshards, each marked with a Jewish name, that probably had been used as the lots. He also said that Josephus reported the stirring speech that the Sicari leader had given to convince his fellows to willingly end their own lives rather than surrender.

We could ride a gondola to the mountaintop and back

When Nancy’s BYU group visited Masada in 1976, they reached the ruins by climbing the remains of the attack ramp–which would have been much easier for Nancy had she had her Merrell hiking boots back then. This time, getting to the top was much easier because we were able to take the multi-passenger gondola that was installed about ten years ago.

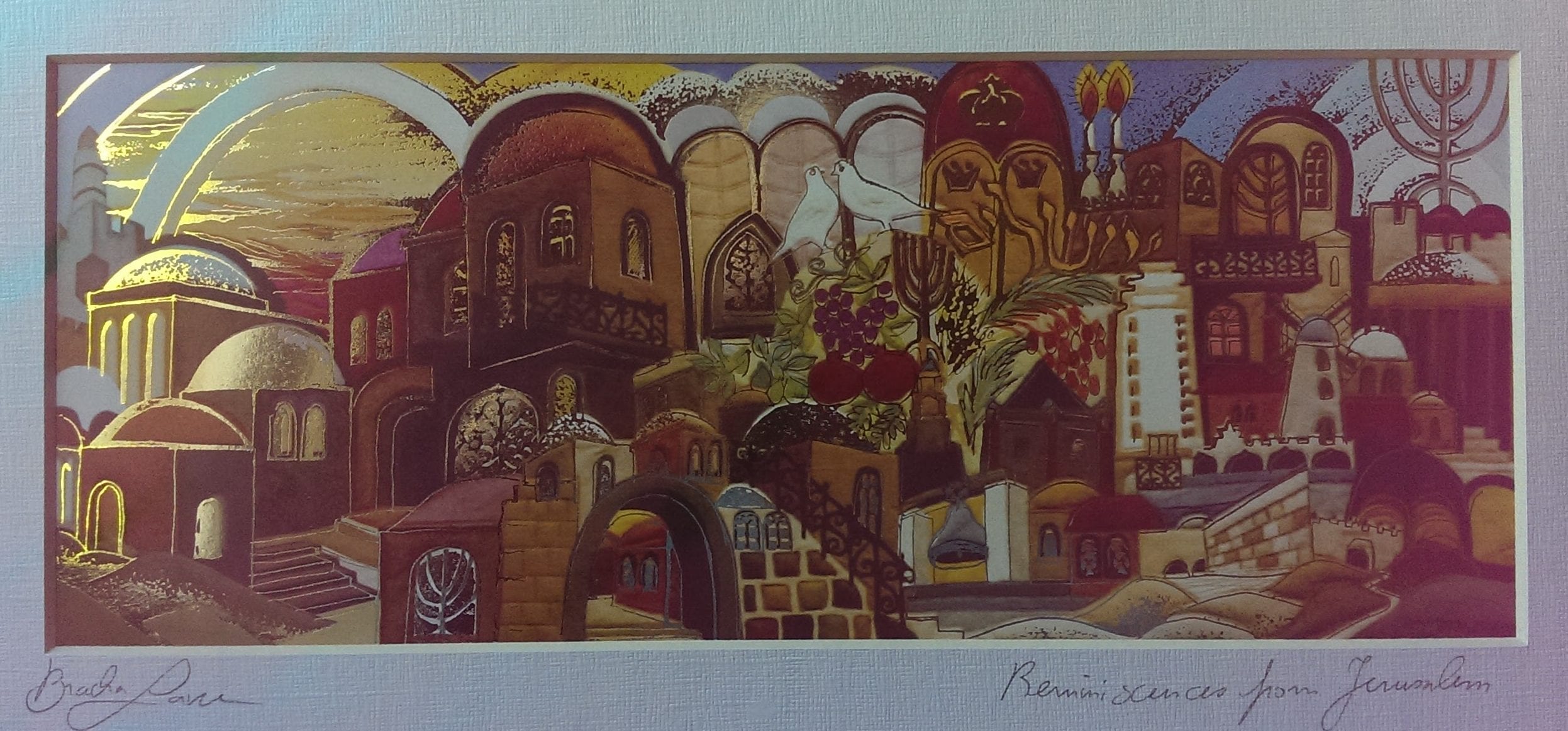

“Reminiscences from Jerusalem” by Bracha Lavee

From Masada, we went to Kalya, a Jewish settlement in the West Bank about a mile from the northern shore of the Dead Sea. We had lunch at the cafeteria and did some shopping there (Nancy purchased a colorful print of Jerusalem by a Polish-Israeli artist) before walking up the hill to visit Qumran National Park.

Emery overlooks excavations at Qumran; the Kalya settlement is under the palms behind her

Qumran

Qumran is the place where the first Dead Sea Scrolls were discovered in 1947. Since then, nearly nine hundred scrolls have been found in the caves that riddle this area. We did not go into any of the caves–most of them are not easy to access, which probably is why the scrolls remained undiscovered for nearly two thousand years–but we could see some of them in the hills beyond the ruins of the community that had preserved them.

Qumran ritual bath

Most scholars believe that the settlement at Qumran, which was established in the second century BC, was home to a community of Essenes, a Jewish sect not explicitly mentioned in the Bible but identified by Josephus and other historians. The Essenes were exclusively male and lived an ascetic, usually celibate lifestyle dedicated to personal purity. This particular community apparently was dedicated also to copying and conserving holy books. Most of these were written on parchment scrolls, although some were on papyrus. The extremely dry climate and the large earthen jars in which they were stored helped them survive the centuries.

Qumran cistern

Qumran bath

The ruins at Qumran include the remains of a cemetery, cisterns, ritual baths, and a dining or assembly hall. In addition, there are pottery kilns, and evidence of an upper story room that may have been the scriptorium where scrolls were copied.

Later this afternoon, we stopped at a public beach on the shore of the Dead Sea and went swimming–if that’s what you can call floating on your back or bottom without letting your face get anywhere near the water. Because the Sea’s saline concentration is about thirty percent, floating took no effort at all; all we had to do was lie back, and just like that, we literally were suspended in the water. But the high salt concentration meant that the slightest open wound, even just a loose cuticle, stung like hell, and heaven help you if any water splashed into your eyes! Even a drop on the lips was unpleasant.

The Dead Sea is not as deadly as was imagined

Nancy & Emery ready to float

One thing we had not expected was the slippery footing as we waded out far enough to be able to float. The black mud did not feel at all like sand, and even though it was soft enough to squish between our toes, it was more viscous than typical mud. Because it’s supposedly therapeutic, most bathers were applying the black mud to their skin. Nancy was reluctant to try it at first because she expected it to feel and act like tar, but she was surprised that the mud rinsed off quite easily. Although the black spread made more of a visual impact than a tactile one, it was a good exfoliant and left our skin feeling very smooth. The water itself also left an unexpectedly smooth sheen that made the skin look lightly oiled, but it did not feel at all greasy. Several local companies are exploiting this natural resource, marketing various lines of Dead Sea skin care products around the world.

The pool area of the Oasis Hotel

We all rinsed off in the public showers after our saline dip, but several of us left our swimsuits on during the ten-minute bus ride to our hotel in Jericho, hoping we would have time before dinner to enjoy the pool and water slide Jim had told us to expect. We were disappointed to find the slide area closed, and the unheated pool was a bit chilly, but it was refreshing nevertheless.

Inlayed design on closet doors

The Oasis Hotel is the most luxurious place we have stayed, a full-service resort furnished with thick carpets, natural marble floors and bathroom fixtures, fluffy towels, and beautiful inlayed designs on the doors of the cedar-lined closets.

At this evening’s devotional, Jim shared some fascinating insights into the history related in the first chapters of the Book of Mormon. When Lehi and his family left Jerusalem in 600 BC (having been warned by God that the city was about to be destroyed), they traveled through the Arabah–the dry southern end of the rift valley that runs from Galilee down to the Gulf of Aqaba. This would have been a familiar route for them, Jim explained, because it’s likely that Lehi was a trader who regularly led caravans to and from the Gulf. (How else could he have moved his family, tents, and provisions out of Jerusalem without attracting attention, unless his neighbors were accustomed to seeing them go off with a train of loaded camels?) When they came near the Red Sea, they turned off the road they knew, however, and headed into the “wilderness”–the uncharted “Empty Quarter” of the Arabian Peninsula, where food is scarce and water is scarcer.

Lehi’s son Nephi, who kept a record of their eight-year sojourn in that wilderness, reported that God had commanded them to avoid making fires, even for cooking the meat that became the mainstay of their diet. Many readers have speculated that this was to prevent the light and smoke from betraying their whereabouts to pursuing enemies, but Jim offered a more intriguing explanation. He reminded us that the Inuit and other arctic tribes live almost exclusively on meat. When European explorers arrived in the Arctic, they adopted the same meat-based diet as their native hosts. However, while the Inuit seemed to suffer no ill effects from the lack of plant-based foods, the Europeans kept getting scurvy. What made the difference? The problem was that the explorers were cooking their meat, while the natives were not. Subsequent studies have determined that raw meat contains sufficient ascorbic acid to prevent scurvy, but that vital compound is destroyed by cooking. Jim went on to tell us that some nomads in the Arabian desert do not cook their meat, either, allowing it to simply dry before consumption. He attests that such dried meat develops a distinct sweetness–which may explain how God could promise Lehi and his family that he would “make their food become sweet” even when it wasn’t cooked.

It was an interesting idea to consider as we sat in the Oasis Hotel’s comfortable chairs, digesting a dinner that included several choices of cooked meats as well as a wide variety of fresh vegetables, fruits, and breads. But having seen with our own eyes the starkness of the desert just beyond the gates of the resort, we can better appreciate what Lehi’s family–and Abraham’s, and Isaac’s, and Jacob’s–must have experienced. And having spent twenty awkward minutes aboard a camel, we are grateful to be traveling through this barren land on a bus with cushioned seats, air conditioning, wifi, and an extremely competent driver.

Leave A Comment