Remembering Christ’s last sermon near the treasury of the temple

This morning we returned to the Temple Mount yet again, but this time, instead of skirting around the sides or burrowing underneath, we climbed a wooden ramp to the top. Before approaching the Muslim shrines that dominate it today, however, we sat in an alcove where the temple’s covered porches once stood. Here, learned men of the past discussed scriptures and disputed points of doctrine. Jim reminded us that this is where Jesus would have preached his last public sermon, calling attention to the widow who gave everything she had to the temple treasury as a fast offering for the poor.

Approaching the Dome of Rock from al-Aqsa Mosque

Many people in the U.S. seem to think that the Temple Mount–or the Noble Sanctuary, as it is known to the Muslim world–is the center of all conflicts in Jerusalem, in Israel, and maybe even the whole Middle East. It is not. While it is true that ownership of this holy site is contested, and that at the moment it is largely under Muslim control, most religious Jews seem content to leave things that way until the Messiah comes to rebuild the temple and free Israel from its oppressors.

On the other hand, many Zionist Jews seem to like provoking the Muslim clerics who patrol the grounds of the Noble Sanctuary. While most Orthodox Jews will not enter the area around the al-Aqsa Mosque and the Dome of the Rock for fear of accidentally violating the most sacred space in their own tradition, less religious Jews regularly climb to the top of the Temple Mount simply to annoy their rivals.

Non-Muslims are allowed to visit the Noble Sanctuary at limited times during the week, but they are not permitted to openly pray, carry religious literature (or anything written in Hebrew, for that matter), or conduct any type of religious discussion there. Adherence to Muslim conventions is strictly enforced. When Mark and Lynn began to slip their arms around each other while posing for a photo in front of the Dome of the Rock, one of the guards immediately ran toward them, shouting, “No touching!”

Jews who wish to enter the Noble Sanctuary have to be escorted by police. (Someone from our group asked Jim, “How do the guards know whether or not someone is Jewish?” Jim replied, “Oh, they know–because it’s usually the same people over and over again.”) During our visit, a group of Zionists came onto the mount with their armed escort, and some Muslim clerics began following them around, repeatedly yelling “Allahu akbar!” (God is great). The contention was disconcerting, but we never felt unsafe ourselves.

The Dome of the Rock

Although we were permitted to walk around and photograph the structures of the Noble Sanctuary atop the Temple Mount, we were not allowed to enter any of them. The best-known of these buildings is the Dome of the Rock, with its blue mosaic octagonal walls and stunning golden roof. (The shrine was completed in the seventh century AD, but the gold plating was not added until the 1960s.) After Mecca and Medina, the Dome is Islam’s third most holy site, marking the spot where Muhammad is said to have ascended to heaven with the angel Gabriel. Early Jews identified the same location as Mount Moriah, where Abraham went to fulfill God’s command to sacrifice his son. (The Bible names Isaac as that son, but Muslims prefer to think it was Ishmael who was tied up and laid on the altar.) Many Jews also believe that the Rock within the Dome is the “foundation stone” spoken of in the Talmud: the place where creation began, and the location of the Most Holy Place within the temple as well. As such, they feel that the Rock is sacred because it remains imbued with the presence of God.

Al-Aqsa Mosque, as seen from the plaza above the El-Marwani Mosque

Nancy was fortunate to see the Rock itself when she visited in 1976 because, at that time, non-Muslims were allowed to enter the Dome (after leaving their shoes outside). She describes it as looking pretty much like any other large piece of bare, uncut limestone one can see around Jerusalem; she found the geometric designs of the building’s classic Islamic decor more intriguing.

The men in Nancy’s BYU group also had been allowed to enter the al-Aqsa Mosque on the south side of the Noble Sanctuary in 1976, but currently it is closed to non-Muslims. This shrine commemorates Muhammad’s Night Journey, in which he was miraculously transported from Mecca to Jerusalem and from thence into heaven on a flying steed. When the Crusaders captured Jerusalem in the eleventh century, al-Aqsa was used as a royal palace and the headquarters of the Knights Templar, but it reverted to a mosque again after Saladin retook the city about a hundred years later.

Dome marking the Holy of Holies

In the 1990s, the Muslims created another mosque under the plaza next to al-Aqsa in a network of vaulted halls built by Herod and known as Solomon’s Stables. The El-Marwani Mosque was established ostensibly to provide more space for worshippers during bad weather, but its construction upset many Jews, who regarded it as the Muslims’ attempt to assert sovereignty over more of the Temple Mount. Others were outraged that bulldozers had been used to dig out an area that deserved much more careful archaeological excavation. Tensions persist between all sorts of interest groups here.

One more small but significant shine engaged our attention before we left the Temple Mount. This domed canopy marks a spot that many scholars feel is likely the actual location of the ancient Holy of Holies, or Most Holy Place, because it more closely corresponds to the location relative to the complex’s eastern gate as described in the books of Kings and Chronicles. That portal, known as the Golden Gate, has been totally blocked since about 1300 AD. Legend has it that the Muslims filled it in to prevent the Messiah from triumphantly marching through it as predicted in the Bible, but Jim says it’s more likely that the city’s rulers just wanted visitors to go around to the south and west sides where the shops were located, because the increased commerce would result in increased tax revenues.

Grounds of the Church of St. Anne

We exited the Temple Mount onto the Via Dolorosa near the Lions’ Gate, which ironically is also called the Sheep Gate because it’s near the market where animals for sacrifice at the temple were bought and sold. Just across the way is the Church of Saint Anne, who, according to legend, is the mother of the Virgin Mary. The church supposedly marks Mary’s birthplace, but we appreciated it mostly for its wonderful acoustics as we sang “Jesus, the Very Thought of Thee.” (There are a number of fine vocalists in our group, so we really enjoy singing together.) We also enjoyed the tranquility of its lovely enclosed garden.

Franciscan monk welcomes us to the church of St. Anne

Door of the Church of St. Anne

St. Anne

Inside the Church of St. Anne

Adjacent to the church are the ruins of the Pool of Bethesda, whose water was supposed by the ancients to have healing properties, especially when it was “troubled” by an angel. When Jesus visited, he required no water to heal a man who had been debilitated for thirty-eight years. He simply asked the man if he wished to be made whole, and then commanded him to “take up [his] bed and walk.” Today we climbed around the remains of the pool’s five porches, remarking to each other that perhaps we were crossing a “bridge over troubled water” even though there was not a lot of water to be seen at the bottom of the pool.

Ruined porches at the Pool of Bethesda

Some water still resides in the Pool of Bethesda

On the street outside the Lions’ Gate, we boarded the bus and headed across the Kidron Valley to the Mount of Olives so we could visit some places we had missed on Saturday. Had we been crows, the trip would have taken maybe three minutes, but our journey took about twenty. Eddie continually impresses us with his ability not only to negotiate heavy traffic in Jerusalem’s serpentine streets, but also to maneuver his 40-passenger bus in and out of spaces that we would be reluctant to try even in our compact cars. Today we sat dumbfounded as we watched him squeeze the bus into a parallel-parking space on a narrow, curving, steeply inclined road filled with pedestrians and the vehicles of other tour groups.

View of the Old City from the Mount of Olives. A vast Muslim cemetery stretches across the terraces below the golden Dome of the Rock

Memorial rocks decorate the sarcophagi in the Jewish cemetery

Coils of barbed wire protect the Jewish cemetery

The Mount of Olives commands a great view of the Temple Mount and beyond, including the Muslim cemetery just outside the eastern wall. A similarly extensive Jewish cemetery is located at the foot of the Mount of Olives. Neither looks like the cemeteries we are familiar with because there is not a shred of grass, just long avenues of stone and sand. As we passed close by the Jewish cemetery, we inquired about all the little rocks scattered on top of the sarcophagi; Jim explained that instead of decorating graves with flowers, visitors here honor the dead by leaving a small stone. Looking across the valley, someone noticed a solemn funeral procession winding into the Muslim cemetery; Jim remarked that the deceased must have died during the night, because Islamic law requires burial within twenty-four hours.

The path down the Mount of Olives

The path we walked on the Mount of Olives is believed to be that taken by Jesus on his triumphal entry into Jerusalem on Palm Sunday. The people recognized Christ as their king that day because he was riding “the foal of an ass”–a young mule. Mules were valued above both donkeys and horses because they combine the best attributes of both: they are strong and sure-footed like donkeys, but smarter and more easily trained. Jim had taught us that in ancient Israel, mules were reserved for royalty, and only the king was allowed to ride one. This is why, when Solomon rode through Jerusalem on David’s own mule, contending factions finally had to acknowledge him as the chosen heir. And this is why Christ’s enemies could accuse him of fomenting rebellion against Rome when he publicly entered the city on a mule a few days before the Passover.

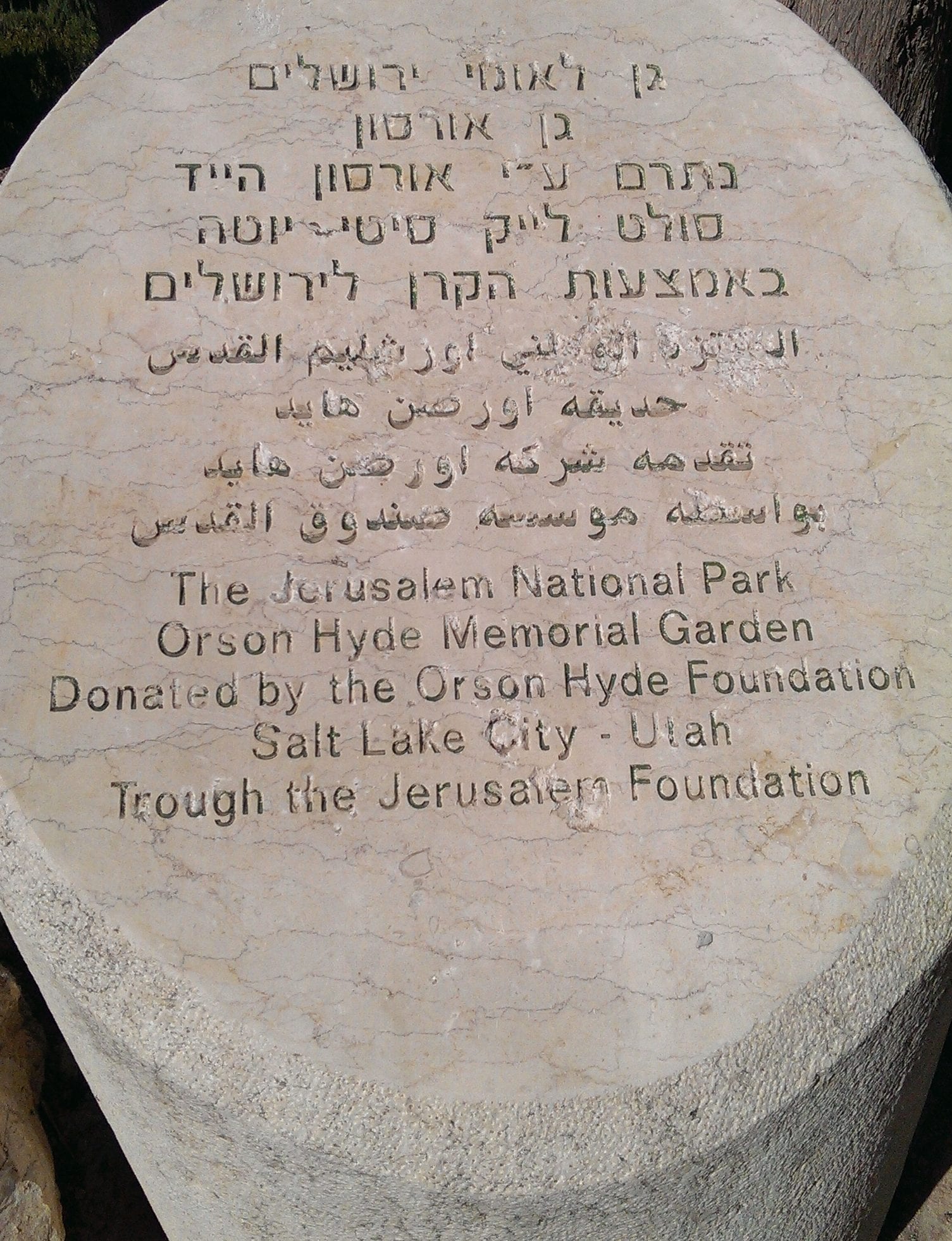

Orson Hyde Memorial

This morning we were walking that route in the opposite direction so we could visit the Orson Hyde Memorial Gardens. Orson Hyde was a nineteenth-century LDS apostle who came here under the direction of Joseph Smith to dedicate the land of Palestine for the return of the Jews. Although we are Christians, Mormons consider ourselves to be part of the House of Israel, given the responsibility to share the word of God with the rest of the world. Like the Jews, we believe that God promised this land to the children of Abraham, and that God’s people must gather here and make the place ready to welcome the Messiah when he comes in his glory. We believe that the dedicatory blessing offered by Orson Hyde in 1841 helped to begin the gathering process, and apparently many Israeli Jews believe that, too, because they have recognized Hyde’s contribution with this memorial.

Devotional in the Orson Hyde Memorial Gardens

During a short devotional in the Memorial Garden, Brian shared that although he had not been motivated to visit the Holy Land by the kind of fervor that we’ve seen displayed this week by other Christian pilgrims, he did feel it was important to experience this land and its spirit. He told us that several members of his extended family had sent prayers for him to offer at the Western Wall; most of them included pleas for God to bless this land and its people with peace.

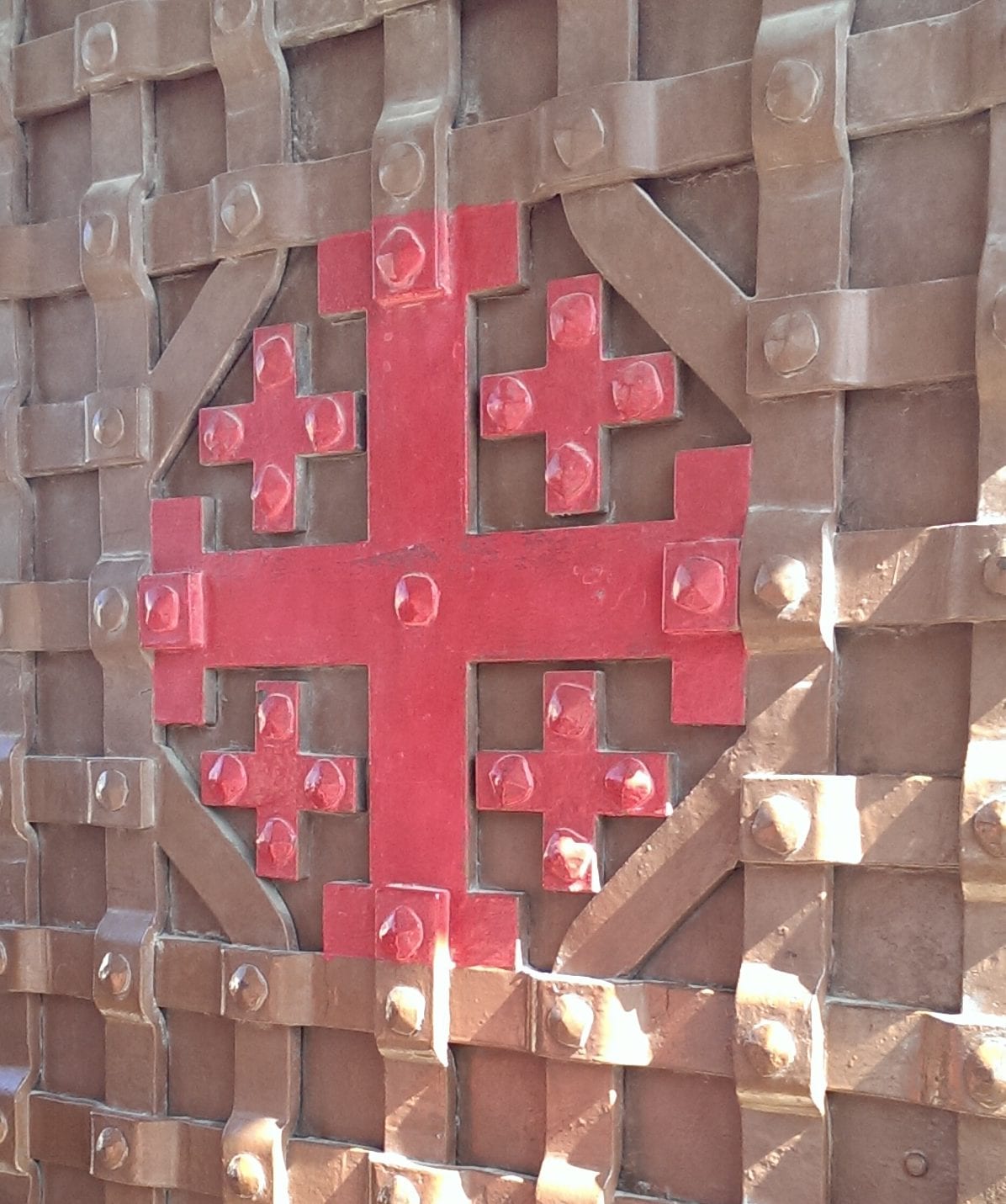

The red cross of the Franciscans marks Gethsemane’s gate

Olives are still harvested in Gethsemane

The rock where Jesus wept in Gethsemane is enshrined within the Church of All Nations

A 2400-year old “witness tree” in the Garden of Gethsemane

We walked through the public Garden of Gethsemane on our way to the Basilica of the Agony, which claims to house the rock where Jesus prayed and wept the night before his crucifixion. The building is also known as the Church of All Nations, and certainly many nationalities were represented by today’s visitors. Inside we heard part of a sermon on forgiveness and peace, presented in English.

Pilgrims from around the world visit the aptly named Church of All Nations near the Garden of Gethsemane

Returning by bus to the other side of the Kidron Valley, we were discharged outside the south wall of the Old City near the Armenian Quarter. This neighborhood is home to the Cenacle, the traditional site of the “upper room” where Christ and his apostles met for the Passover seder now known as the Last Supper. Today we learned that the apostes would have returned to the same room to regroup after the crucifixion, so this is likely where the resurrected Christ appeared and invited them to examine the nail prints in his hands and feet. The disciples continued to meet at this site for years afterward, probably because it was in an area populated mostly by Essenes, a Jewish sect that opposed the Pharisees and Sadducees, and thus was relatively safe for the early Christians.

The Upper Room (photo from Google images)

The upper room currently on this site sits on a foundation probably dating from the Crusader era. Its gothic-style vaulting and an alcove in the Islamic style attest that the building has been remodeled by a variety of owners throughout its long history. Nevertheless, it was easy to picture the room furnished with cushions or low couches arranged in the triclinium style for that special Passover meal nearly two thousand years ago.

The Cenacle was noisy and crowded with other tour groups, so we huddled in a corner to give Amanda (our group’s senior member) and Stephanie (Amanda’s granddaughter) a chance to share their thoughts on the purpose of the sacrament and what partaking of the symbols of Christ’s body and blood means to them. When they were finished, they suggested that we sing a favorite LDS hymn:

How great the wisdom and the love

That filled the courts on high

And sent the Savior from above

To suffer, bleed, and die.

His precious blood he freely spilt;

His life he freely gave,

A sinless sacrifice for guilt,

A dying world to save.

Though we sang quietly, our voices carried through the vaulted room and brought a reverent hush as the other tourists stopped talking and listened. We were only through the first verse when a guard came rushing in to tell us that we had to stop, but the leader of a group of Brazilian pilgrims asked him to please let us continue because he and his group found our music very moving.

It was now close to noon. Jim had told us that we could plan to get lunch from a snack bar on the grounds of a complex that includes the Palace of Caiaphas, our next stop. However, when we arrived the man who operated the snack bar was just closing up, explaining that he always closed from 12 to 2 pm–even though he sold falafel and other sandwiches. (Someone remarked that clearly this man was a “hireling” and not the owner.) Others from our group looked on hungrily as the two of us again pulled stuffed pita pockets from our backpacks.

When Jesus was arrested in the Garden of Gethsemane, he was taken to the Palace of Caiaphas, the Jewish high priest. Here the Savior was questioned, humiliated, and beaten. The Sanhedrin–the council of the Jews’ elders and scribes–determined that since Jesus claimed to be the Son of God, he was guilty of blasphemy, a religious crime punishable by death. The problem for the Sanhedrin was that, under Roman rule, they had no authority to execute prisoners; so, since Jesus did not deny his followers’ claim that he was also King of the Jews, they decided to accuse him of insurrection, another capital crime that should pass muster with Pilate, the Roman governor.

Steps leading to Caiaphas’s Palace

Although the high priest’s palace was probably leveled along with the rest of Jerusalem in 70 AD, the complex we visited today is likely the right spot because it not only fits contemporary descriptons, but also because an ossuary engraved with the Caiaphas family name was found in a nearby tomb. Jim said that the excavated steps leading to the palace could very well have been those that Jesus mounted when he was brought here from Gethsemane.

Palace dungeon

Inside the slime pit

It was chilling to descend into the palace dungeon, where Christ probably was held overnight. We saw the rope-holes in the overhead beams where prisoners’ hands would have been tied up while the guards flogged them. We looked into the slime pit where the unluckiest offenders would have been thrown to drown in muck and sewage when they became too weak to stand. Jim suggested that even though none of the gospel writers mention this pit, it’s likely that Christ, as a capital prisoner, would have been subjected to its horrors before he was turned over to Pilate. It was a sobering thought.

“I know him not”

Probable porch where Peter denied knowing Jesus

The cock atop St. Peter in Gallicantu

Outside the palace is the porch where Peter would have stood among the high priest’s servants, hoping that he might hear news of his master without being recognized. The dome of the Church of Saint Peter in Gallicantu, also part of this complex, is topped with a golden rooster, a reminder of the crowing cock that brought Peter to bitter tears after he denied any acquaintance with Jesus of Nazareth, three times.

We were a more subdued group when we returned to the bus and drove around the western side of the Old City toward our final stop of the afternoon.

A bus depot occupies the probable site of the crucifixion

Even though the Church of the Holy Sepulchre claims to enclose the sites where Jesus was crucified and buried, the more likely location for these events is near a promontory just outside the Damascus Gate (and just around the corner from our hotel). The Bible refers to the site of the crucifixion as Golgotha or Calvary, both of which translate as “the place of a skull,” and we can attest that a natural formation that looks much like a skull is visible on the side of this promontory. Although artists usually depict the scene of Christ’s crucifixion with three tall crosses atop a hill, Jim told us that the Romans would have crucified offenders on relatively short crosses placed at street level, where passersby could more easily get in their faces to mock and spit at them. The idea creates a more distressing picture, but it makes sense. The fact that the place where this monumental event probably occured is now a busy bus depot instead of a sacred shrine is also distressing–but somehow that seems fitting.

Golgotha or “Place of the Skull” (Our guide said that part of the skull-like formation cracked and fell away during a storm earlier this year)

The Garden Tomb

We got a good view of the skull from the ridge above the bus depot, where there is a much more peaceful place to ponder the crucifixion and resurrection. Simply called the Garden Tomb, this site is thought to be on property once owned by Joseph of Arimathea, the rich man who offered a newly hewn tomb in his garden as a burial place for the Savior. Such a tomb was located here by archaeologists in 1867; further excavation also revealed a nearby winepress and cistern, suggesting that the property had indeed been a garden in ancient times.

Michael enters the tomb

Inside the tomb

Currently, the tomb and the lovely surrounding garden are maintained by a nondenominational charitable trust. Bertil, the Swedish volunteer who led our tour, explained that no one really knows where Jesus was crucified or where his body was placed, and that it doesn’t really matter. “What matters,” he said, “is that he rose from the tomb.”

Our Swedish guide shared our faith in Christ

Cistern and wine press in the garden

We appreciated Bertil’s sincere testimony of the reality of the resurrection, and the spirit of serenity that pervades the garden. While our group was seated where we could see the entrance to the tomb, Shauna and Scott shared their witness of Jesus Christ and his saving mission, and then we all sang “He Is Risen” and “Christ the Lord Is Risen Today.” After that, each of us had a chance to enter the tomb and think about how astonished Mary Magdalene, Peter, John, and the other disciples must have been to find it similarly empty on that Sunday morning long ago.

It was a very short ride back to the hotel. Most of us went inside only long enough to drop off the things we had purchased at the Garden Tomb Association’s gift shop (Nancy bought a little creche made of wool felt by special-needs children in Bethlehem) before we regathered in the lobby to walk the ramparts.

Walking toward the Jaffa Gate

Have you ever wondered what you’re singing about when you get to that line in “The Star-Spangled Banner” that goes: “O’er the ramparts we watched ..”? Well, we’ll tell you: a rampart is a fortified embankment or wall used for protection. Jerusalem’s ramparts are the forty-foot limestone walls that surround the entire Old City. Those that exist today were built in the sixteenth century by Suleiman the Magnificent, ruler of the Ottoman Empire.

Walking the ramparts had been one of Nancy’s favorite activities when she had been here as a college student. In those days, one could simply mount one of many stairways that led to the top of the city wall and wander along the narrow walkways as one pleased. Since then, however, someone realized that this experience could be monetized (in a less politically correct era, we might have inserted a Jewish joke here), so now you have to go to the stairway just inside the Jaffa Gate and buy a $5 ticket–and you have to get there before the turnstile is locked at 4:00 p.m. So at 3:45, we were hurrying toward the Jaffa Gate on the west side of the Old City.

Buy your tickets here (shekels only)

At every venue our group has visited this week in both Jordan and Israel, merchants have been happy to accept our US dollars. However, when we arrived at the ticket counter for the Ramparts Walk, we were met with a sign that said: “16 INS (shekels only).” This was new, said Jim; they’d always been able to pay in dollars before. And right now it was a problem, because most people in our group had never bothered to exchange currency and we had only a few minutes to do so before the gate would close.

If we had carried bows, we could have shot invaders

Walking the ramparts includes going up and down a lot of stairs

“Not a problem!” said the ticket seller. “There’s a currency exchange right next door!” And so there was–an exchange that charged an exhorbitant ten percent, which they probably split with the owner of the ticket office. (We half expected the ticket seller to appear behind the exchange counter himself.) Shekels in hand, we bought our tickets and hurried through the turnstile just before the attendant locked it up.

Holiday decorations going up on a rooftop in the Christian Quarter

A residential rooftop retreat

A backyard playground

The allure of the Ramparts Walk is that it provides a unique and fascinating view of Jerusalem. We could look not only out across the rooftops of the whole city, but also down on residential patios and schoolyards, behind the walls of churches, synagogues, and mosques, and into the storage areas of shops, restaurants and other businesses. At one point, we came upon a soccer field where a group of teenage boys were going through some practice drills. Farther along, we met a Dutch couple just sitting down to dinner on their outdoor terrace. They invited us to join them, but since we weren’t sure they could really handle all twenty of us, we politely declined.

Suleiman had stones on top of Jerusalem’s watchtowers carved to look as though they were soldiers wearing pointed helmets to fool potential invaders

The sun had set by the time we got to the exit at Herod’s Gate about an hour later. Fortunately, it was only a short walk back to the Golden Walls Hotel, where we had a chance to relax for a little while before dinner. Each of us filled our plates a couple of times, but we still had room to try the various flavors of baklava that Rusty passed around afterward in celebration of Marguerite’s birthday.

At tonight’s after-dinner devotional, Heidi spoke about miracles–not only the big ones, but also the small ones that we may not immediately recognize. The opportunity to visit the Holy Land this year has been a big miracle for us, but no less miraculous are the wonderful people in our group with whom we have shared the experience.

Leave A Comment