The outdoor terrace atop a cafe (left) overlooks excavated areas on the west side of the Temple Mount

Jerusalem is a city of layers. Throughout its history, the city has been conquered, more or less destroyed, and then rebuilt at least seventeen times. As at Jericho, not only does this present archaeologists with the challenge of deciphering which layer they dealing with at any given location, but it also presents the challenge of deciding which layer to conserve. If they stop digging to preserve the features of one layer, then they prevent everyone from understanding and appreciating what might be found in the layers that lie farther down. And then there is the issue of what to do when historically significant ruins are discovered underneath the homes, schools, and businesses of the city’s living inhabitants.

The challenges presented by Jerusalem’s physical layers also serve as a metaphor for the challenges associated with its religious and political layers. All of these issues became dramatically apparent today as we walked around much of the Old City–sometimes on the surface, sometimes high above it, and sometimes in dimly-lit caverns under the ground.

Morning prayers at the Western Wall

Passing through the Damascus Gate near our hotel, we walked down El Wad ha-Gai Street once again toward the southwest corner of the Temple Mount. After going through the security checkpoint, we stopped for a few minutes at the Western Wall to take the photos we had not been able to get on Friday evening, but then we began descending through the layers of space and time in excavations under the Mount behind the Wall so we could see more of what has been uncovered in recent years, and better appreciate the historical and current significance of the sacred structure.

Stone of the original pathway along the Western Wall

Originally constructed by King Solomon in the tenth century BC, the elaborate temple complex was burned by the Babylonians about four hundred years later. (For those of us who had always wondered how a solid-stone structure could be “burned,” Jim explained that the invaders would have used combustible material to start fires around the foundation blocks; the resulting heat would then cause moisture within the limestone to expand, exploding the blocks and causing the whole superstructure to tumble.) The rest of Jerusalem was destroyed at the same time, and most of Hebrew population of Judaea was carried off to Babylon, but when the Persians conquered the Babylonians a couple of generations later, many Judaeans were allowed to return to Jerusalem, and the temple was rebuilt. That “Second Temple” was never technically destroyed, although it suffered plenty of desecration along with normal wear and tear over the next four hundred years. By the first century BC, it was in need of a major renovation, and Herod the Great, king of Judaea (although himself subject to Rome) was just the man to do it.

By all accounts, Herod was a terrific construction contractor, even if he was a despicable human being, and the temple in Jerusalem became his masterpiece. He was responsible for expanding the area of the Temple Mount by extending the foundations and building up the corners, so what originally had been a medium-size rounded hilltop became a huge level platform covering about thrity-five acres. Structures atop the platform, including the Holy Place that only priests were allowed to enter, and long, covered porches where people assembled to be instructed and discuss the scriptures, were raised to new, impressive heights. Herod’s Temple (it seems heresy to call it that, but such it was) is the temple that Christ frequented during his mortal ministry. The magnificient edifice was not destined to endure, however. When the Jews rebelled against their Roman rulers about thirty years after Christ’s crucifixion, Jerusalem was sacked and the temple was burned again–just as Jesus had prophesied.

Since then, the place Jews and Christians refer to as the Temple Mount has been home to a Roman temple dedicated to Zeus, and then to the Dome of the Rock, a Muslim shrine marking the site where Muhammad is said to have ascended into heaven with the angel Gabriel. The Dome was completed in 691 AD and is still standing, having long outlasted any of the temples built on this hill that were dedicated to Jehovah. (We’ll come back to the Dome of the Rock later; first, we need to explore what lies under and around it.)

Wilson’s Arch

Herod’s Bridge

Blocked-in Western Wall entrance

Our path this morning took us from the court in front of the Western Wall north to Wilson’s Arch, which is part of a bridge that Herod built to give the upper city easier access to the Temple Mount. It is named for the surveyor who identified it while trying to upgrade the city’s water system in the 1800s, and it is now–as it must have been when Wilson found it–well under the current level of Jerusalem’s streets. Today, the arch marks the entrance to a network of underground passages that lead along Herod’s Bridge and then under the Temple Mount itself. At the end of the bridge we could see the arched gateway to the temple. No one has been able to go through that gate for centuries, however, because it was blocked off after Muslims took control of Jerusalem in the seventh century AD.

Nancy’s previous visit to Israel had taken place less than ten years after the Six-Day War, in which Israeli forces captured Jerusalem’s Old City from the Jordanians. At that time, the Western Wall was the only remaining portion of Herod’s Temple that was not buried beneath rubble, so it became the focal point of Jewish worship–and excavation. Crews began working immediately to uncover more of the Wall so more of the faithful would be able to pray at this holy site. (In 1976, only males were allowed to enter the court in front of the Wall, so Nancy and her female companions had to observe from a distance.) Today, we were intrigued to learn that religious Jews avoid entering the compound atop the Temple Mount lest they inadvertently trespass on the “Most Holy Place”–the site where the temple’s sanctuary once stood. That space was reserved only for the High Priest, and only on the annual Day of Atonement. But even secular Jews who could not care less about descecrating an ancient sanctuary steer clear of the top of the Temple Mount to avoid confrontations with the Muslims who currently control the area.

So the Western Wall Foundation, which funds archaeological work at the Temple Mount, is concentrating on what lies far beneath the Muslim shrines. Most of what we saw there this morning has been unearthed only in the past ten years. Jim told us that since he began leading tours around Jerusalem, he has noticed an increasing sense of urgency in excavation projects at the temple–as if the Jews are “hastening the work” in anticipation of the “last days,” just as the Mormons are trying to do. Indeed, at an area believed to be directly beneath the original site of the Most Holy Place, down a “secret passageway” used by ancient priests, a group of faithful Jewish women maintains a round-the-clock prayer vigil, entreating Jehovah to send the Messiah–ASAP.

Limestone quarry

Original 600-ton foundation stone of the Temple Mount

Herod’s trademark “framed” stone dressing

As we continued to descend into the underground caverns, we passed the quarry where much of the limestone for the temple had been cut. Jim made sure that we appreciated the size of the foundation blocks Herod’s workmen had laid: some of them are more than forty feet long and weigh over six hundred tons. (We are continually amazed by what ancient builders were able to accomplish without gasoline-powered engines or electricity!) Jim also pointed out the way Herod put his personal stamp on this and other construction projects: all the stone blocks in the buildings he commissioned were cut with a distinctive, smooth frame around the edges. Even portions of the foundation’s bedrock were similarly dressed for a uniform appearance.

Underground aqueduct

Cistern

Deeper under the Mount, we walked through a system of underground aqueducts. Unlike Hezekiah’s Tunnel, which we had visited last Friday, these were almost completely dry. The cisterns into which they fed held some water–but not anything anyone would want to drink.

Ascending into the light outside the temple complex, we walked back to the Via Dolorosa and began visiting some of Jerusalem’s Stations of the Cross. Second on the traditional trail is the Church of the Condemnation, which memorializes the place where Pilate condemned Jesus to crucifixion. It is located across the street from the Antonia Fortress, the guard outpost Herod had built at the northwest corner of the Temple Mount. Last Thursday, we had the opportunity to look down from the upper floors of the fortress onto the Temple Mount, but today we went into the the bowels of the building, where the soldiers’ horses would have been kept. Jim directed our attention to the original paving stones on which we walked, cut with grooves to provide more traction for shoed horses. Here we also saw some excellent examples of the type of manger baby Jesus would have been laid in.

Along the Via Dolorosa

Church of the Condemnation

Antonia Fortress stables

Manger

We had to push past a group of African pilgrims at Station V, recalling the point where Simon of Cyrene was conscripted to carry Christ’s cross

The dome and apse of the Church of the Holy Sepulchre are hard to see from the street

Other buildings crowd the entrance to the Church of the Holy Sepulchre

Unlike most of the pilgrims we met along the Via Dolorosa, we did not stop at every Station of the Cross. Instead, we made our way directly to the Church of the Holy Sepulchre in the Christian Quarter. When Saint Helena, mother of Constantine, the first Christian emperor of the Roman Empire, visited Palestine in 326 AD, she wanted to know exactly where the great events of the Savior’s life had taken place. Even though pagan Romans had likely destroyed everything significant to Christians centuries earlier, Helena’s handlers nevertheless pointed out the exact locations of Jesus’s death and burial. They even managed to rustle up the three crosses on which Christ and the two thieves had been crucified. (Through miraculous means, Helena reportedly determined which was the “True Cross” on which the Savior had died, and then took it back to Rome with her.) Helena arranged for the construction of an appropriate shrine to enclose the places she was shown; the Church of the Holy Sepulchre thus houses some of the holiest sites in all Christendom. Among the thousands of visitors who had come from around the globe to worship there today, our little group seemed somewhat lost. A stern Armenian priest watched over the shrine of the sepulchre, trying to keep order among the throngs, but as at the Church of the Nativity in Bethlehem (another building for which Helena is responsible), the crush made it difficult for us to feel reverent.

Many pilgrims lay personal items on the stone slab where the body of Christ is supposed to have been prepared for burial, hoping that their belongings will be imbued with mystical powers

The traditional location of the cross

The traditional location of the tomb

Visitors to the shrine of the tomb are kept in line by an Armenian priest

Lunch at the Fountain Cafe

Falafel sandwich

After escaping from the Church of the Holy Sepulchre, we stopped for lunch at the Fountain Café, where we watched the cook fry the falafel most of us had ordered. These are balls made of ground chickpeas, served in pita bread with sliced peppers, tomatoes, and lettuce, and a slightly spicy yogurt-based sauce. These were especially delicious because they were so freshly made. Group members Heidi and Jeff, ever on the lookout for their favorite Magnum ice cream bars, found some at a shop nearby and bargained for a quantity discount so the rest of us could indulge along with them.

In the Christian Quarter

Countless shops tempt tourists in the Christian Quarter

Cafe tables crowd around the central fountain in the Christian Quarter

Exotic spices for sale in bulk at a specialty shop

Street vendor with his baked goods

With a few minutes of free time before we reconvened to continue our tour, we strolled the streets around the café and looked for more bargains in the colorful shops. Nancy saw many blouses like the one she had hoped to buy a few days ago, but again she could not find a black one in her size.

Cardo Maximus

Nancy in a now-empty shop along the Cardo Maximus

Our group’s first stop after lunch was at an excavated portion of the Cardo Maximus, the “Great Heart” of the city where tourists of the Roman era would have mingled with residents buying oil, spices, metalware, and other goods. Seeing the remains of a wide, paved street lined with colonnades made us reset our mental images of the kind of shopping district where the people of Jesus’s time would have traded.

The men of our group pose amid the rubble left by the wall of the Temple Mount

From the Cardo, we headed east through the Jewish Quarter to the south side of the Temple Mount, passing by part of a city wall that has existed since the time of David. Near the southwest corner of the Temple Mount, archaeologists have intentionally left piles of rubble to give visitors a better understanding of what centuries of destruction looks like.

The pinnacle of the temple

Nearby is a facsimile of an inscribed stone found atop this corner, indicating that this was where the trumpeter would stand to sound the call for official announcements. Jim explained that this corner of the temple complex also is likely to be the “pinnacle” where Satan suggested that Jesus throw himself down and then hope the angelic rescue squad would arrive before he hit the ground. (Jesus did not succumb to the temptation.)

Closed-up south wall exits

From the corner, we moved around to the south wall, which has two portals through which the public could enter and exit the Temple Mount in the days of Herod. No more: both gates have been completely filled in. The Al-Aqsa Mosque currently stands above the Huldah Gate, and in recent years the Muslims have built another mosque underground behind the Beautiful Gate to prevent the Jews from claiming the space.

Cleansing pool

However, excavation has continued in the Jerusalem Archaeological Park in front of the gates, revealing miqva’ot, large pools where Jews would ritually cleanse themselves before entering the Temple Mount to offer sacrifices. The Huldah Gate once opened onto the processional steps leading down to the Pool of Siloam (which we had visited on Friday morning); the Beautiful Gate led to Solomon’s Porch, where Peter demonstrated his faith and power by healing a lame beggar in the name of Christ.

The Al-Aqsa Mosque looms over excavations in the Jersusalem Archaeological Park

The archaeological park includes the Davidson Center and some other modern buildings where one can see ancient artifacts and watch a film that shows what a visitor to the temple in the meridian of time might have experienced.

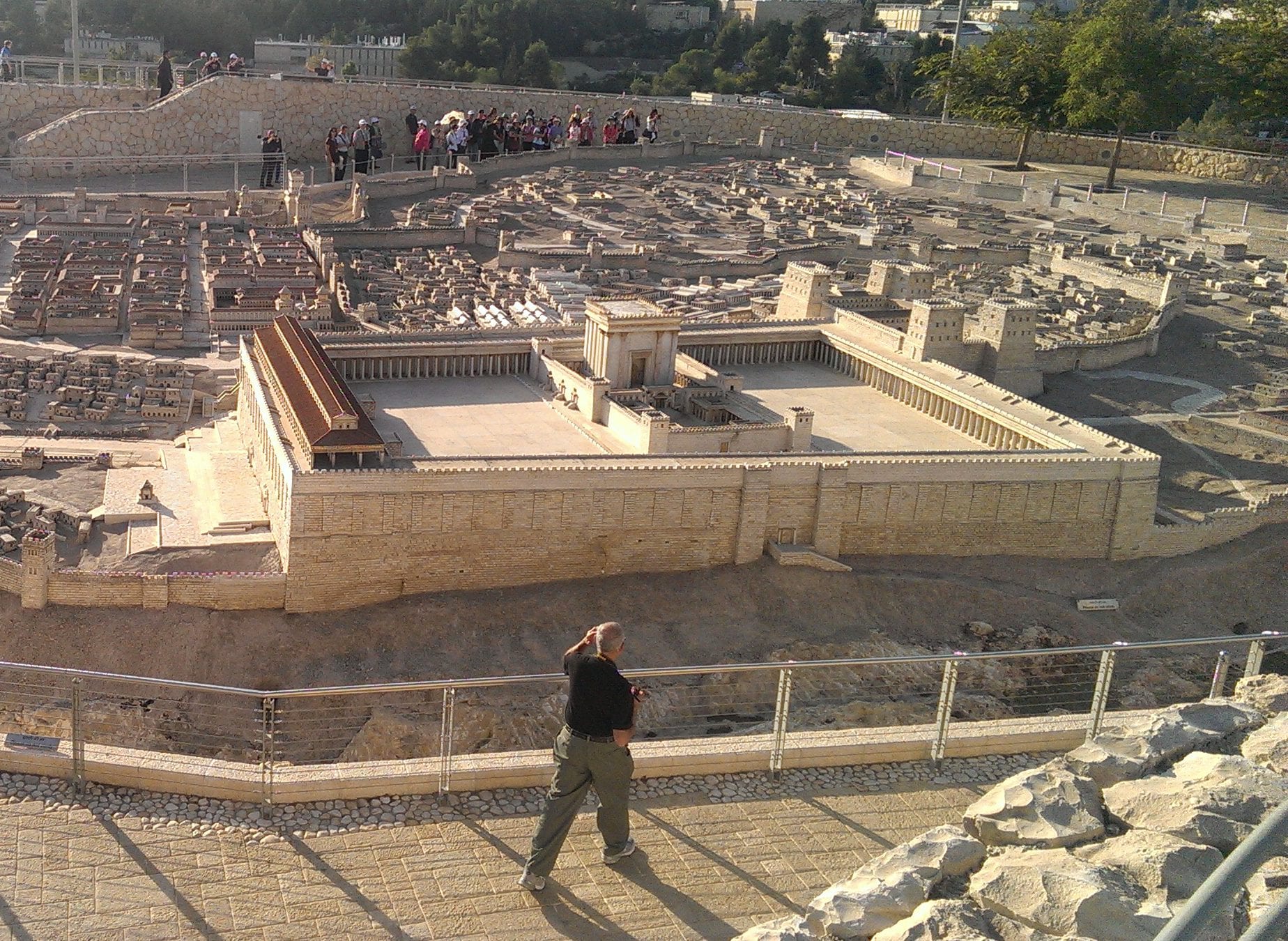

The Temple Mount dominates a model of Jerusalem’s Old City

Knesset

Our bus was waiting at the bottom of the hill when we left the Davidson Center. Once everyone had boarded, Eddie drove us across Jerusalem to the Israel Museum, another modern complex that includes the Shrine of the Book and a huge model of the Old City as it would have appeared after the Second Temple was completed. The Givat Ram neighborhood, where the Musuem is located, added a completely different layer to our Jerusalem experience: the streets are wider, the architecture is more contemporary, and the atmosphere is more “upscale.” The Knesset (the Israeli parliament) is located here as well.

Shrine of the Book

The Shrine of the Book houses Israel’s permanent collection of the Dead Sea Scrolls. Although we had probably seen more of the actual scrolls when a traveling exhibit came to Cincinnati a couple of years ago, it was still interesting to see them in this context. The striking Shrine is built to resemble the lid of one of the round clay jars in which the ancient scrolls were stored. (We plan to visit Qumran, the site near the Dead Sea where the scrolls were discovered, later this week.)

“Profile” by Picasso (1967)

“Three Piece Sculpture” by Henry Moore (1969)

This afternoon we didn’t have time to visit the rest of the Israel Museum, but we did notice that the sculpture garden on the grounds includes a Picasso and a Henry Moore.

By the time we returned to the Golden Walls Hotel this afternoon, we felt like we’d already had a full day–but it wasn’t over yet. Some of us made a trip to a nearby convenience store to get more bottled water, and then Nancy made a foray back into Old City by herself, searching the suq for an embroidered black blouse. Just when she had decided to give up and go back to the hotel for dinner, she found just what she was looking for. After bargaining the cost down to one-third of the original asking price, she handed over a ten-dollar bill and returned to the hotel feeling very pleased.

One of the matkot-inspired artworks in the BYU Center’s gallery

Our group ate dinner earlier than usual so we could head back to the BYU Jerusalem Center for “Sunday Night Classics”–one of a series of classical music concerts presented at the center each week. Tonight we heard pieces by Haydn and Mendelssohn expertly performed by the Idan Trio. The violinist, cellist, and pianist are based in Jerusalem but have performed in concert halls around the world. Before the program began, we also enjoyed an exhibit in the Center’s art gallery that featured related works by contemporary Israeli artists. Each piece in the show was inspired by the game of matkot, a popular Israeli pastime played with a rubber ball and two paddles.

Idan Trio playing for Sunday Night Classics series

When Michael learned that the Sunday-night concert series is curated by a local musician under the direction of a senior missionary from the U.S. (currently, a retired music professor from BYU-Idaho), he decided that that was a mission he would love to get called to–even though living in this chaotic, many-layered city for eighteen months probably would not be easy.

Leave A Comment