Waiting to enter Hezekiah’s Tunnel

We had been warned about the hike through Hezekiah’s Tunnel: Wear shorts. Wear water shoes. Wear a headlamp. If you tend to get claustrophobic, plan to stay with the bus driver and meet us at the other end. But hey, we’d already slogged through mud and encountered thigh-high water in that gorge in Petra with no such advance warnings, so how bad could a walk through one of Jerusalem’s most popular tourist attractions be?

Nancy inside the tunnel

Exit from the tunnel

Nancy had read about Hezekiah’s tunnel in Jehovah and the World of the Old Testament (an excellent book, by the way), but had not seen it during her 1976 visit to Israel because, at the time, it was not open to tourists. Here’s the history: Although Jerusalem had been an important military stronghold since the time of King David (who lived around 1000 BC), the fortified city had one big weakness: its primary source of water, the Gihon Spring, was outside the city walls. Anyone going to fetch water was thus exposed to potential enemy attack, and the spring itself was vulnerable to capture. Around 700 BC, after the Assyrians had already overrun the Northern Kingdom of Israel, Judah’s King Hezekiah decided that it would be prudent to do something about Jerusalem’s water problem before the Assyrians showed up to besiege the City of David.

Michael emerges from the tunnel

What Hezekiah proposed was the construction of a tunnel to direct water from the Gihon Spring to the Pool of Siloam, located within the wall on the south side of the city. The spring would then be buried under enough rubble to prevent the enemy from finding it. This project would require digging through at least 1200 feet of solid bedrock with nothing more sophisticated than chisels, hammers, and some mighty strong arms. Archaeologists who rediscovered the tunnel in the nineteenth century AD found an inscription inside stating that the project had been executed by two teams working from opposite ends, which may explain why the tunnel is far from straight and exhibits some obvious course-corrections along its 1777-foot length. Apparently, the digging crews used auditory cues to help each other try to stay on course, but no one is sure exactly how they were able to accomplish the task as well as they did, and no one knows exactly how long the project took to complete.

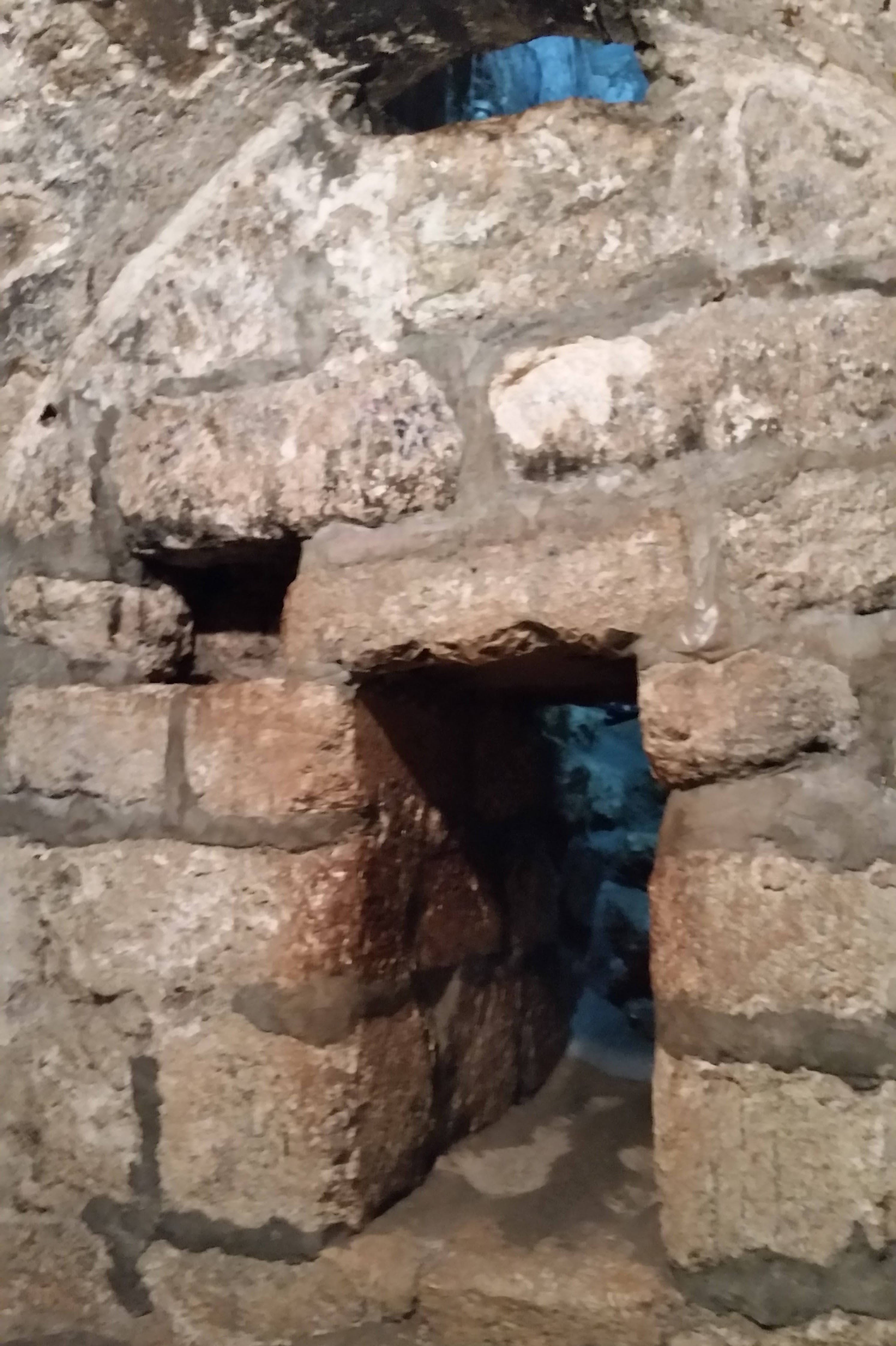

Outside bottom of Hezekiah’s Tunnel

Women at the Pool of Siloam

A sign near the entrance indicated that we should expect the water to be more than two feet deep when we entered the tunnel, and it was. However, the level soon dropped, so most of the way we were sloshing through only six or eight inches of cool but not frigid spring water (no sewage–thank heaven!). The width of the passage is consistent–only enough for one person–but the ceiling height varies considerably. In some places, even Nancy had to crouch down to pass through, while in others the ceiling soared several feet over our heads. Jim explained that the height variation resulted from adjustments to achieve the right floor angle to allow water to flow evenly from the spring to the pool. After we had walked/waded for about forty minutes, we could tell that we must be nearing the exit because the water level began to rise again. Soon we were able to switch off our headlamps and climb into the sunlight at the Pool of Siloam. When we sat down on the steps there to wait for everyone in our group to emerge, Jim reminded us that, like every other watering hole in ancient times, this pool had been a popular gathering place for the people of the city, especially the women. The female half of our group decided to recreate the convivial atmosphere for a photo.

Processional steps to the south wall

All over Jerusalem, the excavation of historic structures takes place underground while everyday life goes on overhead in regular homes and businesses. Within the last few years, workers have uncovered part of the long avenue of steps that once led all the way from the Pool of Siloam to the south entrance of the temple. As we left the pool area, Jim directed us into a nearby excavation tunnel where we could see some of these “processional steps”–so-called because of their alternating wide-short-wide pattern. Other tourist groups continued to pass by outside, but the relative seclusion of the dig tunnel gave us a chance to pull out our scriptures and review some of the events that had taken place on these steps two thousand years ago. On certain days, Jim explained, the high priest would lead a procession up the stairs from the Pool of Siloam to the temple, carrying a sacred vessel filled the “living” spring water needed for ritual purification. And it was down these stairs to the Pool of Siloam that the blind man went to wash, after Jesus anointed his eyes with clay made from his own spittle. The story of the miraculous healing took on new meaning for us as we pictured the man, here on these very steps, blinking in the light for the very first time.

Looking across the canyon toward the ancient road from Jerusalem to Jericho. If you look closely, you can see a goatherd watering his flock at a spring (under the trees in the dark patch in the center of the photo)

Yesterday we had to leave Zaid and Hani, our Jordanian guide and driver, behind when we entered Israel. Now their Israeli counterparts, Samir and Eddie, were waiting to direct us down the hill to the bus when we finished our meeting on the processional steps. Our original itinerary called for a trip to Nablus in the West Bank to visit Jacob’s well (where Jesus taught the Samaritan woman about living water) and Joseph’s tomb, but since the tomb had been torched a couple of week ago and the situation remains edgy, travel to the area seemed imprudent, so instead we headed toward Jericho.

Judith teaches on the road to Jericho

Michael contemplates the parable of the Good Samaritan

The modern highway taken by our bus parallels the ancient road that provided the setting for the parable of the Good Samaritan. Seeing the rugged, desolate landscape, it was easy for us to picture how a lone wayfarer could fall victim to bandits–and how more fortunate travelers on the narrow road would have to deliberately ignore him to pass by. When we got off the bus at the overlook, Judith gave the first of several devotionals that various members of our group have planned to present at designated sites during our journey together. She helped us understand how the story of the victimized Jew, aided by the compassionate Samaritan, can be seen as an allegory of our journey through mortality, with Christ as our succoring Savior.

A fountain in Jericho, the world’s oldest city

Ann and Mark T, Lynn and Mark M, and Pat relaxing at the Temptations Tourist Center

Excavations in Jericho

Remains of a Canaanite-era tower in Jericho

In Jericho, we took a lunch break at a large inn with an extensive gift shop that was aptly named the “Temptations Tourist Center”–ostensibly because the devil’s attempts to sway Jesus from his perfect path are believed to have occurred in the mountains nearby, but probably also because the cafe tempts tourists with many varieties of Magnum ice cream bars.

A short walk from the inn is an excavation site with some ruins–very old, even by Middle Eastern standards–that many believe to be the remains of the ancient Canaanite city of Jericho. As at many of the historic sites here in the Holy Land, it’s impossible to know for sure whether these were the actual walls that “came a-tumblin’ down” when the Israelite army blew its horns, but to us they looked pretty convincing. One of the difficulties for archaeologists, we have learned, is that dating artifacts usually depends on where they are found among dozens of layers of dirt and debris, and those layers often do not lie undisturbed over the course of centuries. When a city is destroyed either by an enemy army or by natural disaster, conquerors or survivors may simply build anew on the existing foundations, or others may raid the site for nice building blocks they can carry off to erect their own structures. In the case of Jericho, which claims to be the oldest city in the world, archaeologists have identified about thirty layers of historical strata dating back nearly six thousand years.

Today, Jericho thrives on its date groves and modern resorts

After our visit to Jericho, we headed back toward Jerusalem, stopping first in the little village of Bethany. Now a suburb on the “wrong” side of town, Bethany is still home to the kind of working poor that Jesus lived among. His dear friends Martha, Mary, and Lazarus lived in Bethany, and it is likely that Jesus often stayed at their home when he came to Jerusalem to observe feast days and teach in the temple. (Jim Gee speculates that perhaps the siblings had once lived near Joseph and Mary’s family in Galilee, and that Jesus and Lazarus had been childhood friends.) As with most New Testament sites, the purported home of Martha, Mary, and Lazarus is marked by a memorial church. Here in Bethany, the sanctuary is very simple–which seems appropriate for the locale.

Outside Lazarus’s Tomb

Inside Lazarus’s Tomb

Since Bethany was Lazarus’s home, this is also where Lazarus died and was restored to life by the Savior. The tomb where he had been laid (at least, the traditional burial site) is a little way up the street from the church and then down a couple of flights of steps, under some more modern homes. It’s small (nothing like the tombs of Petra), so only five or six people can enter at a time. Before we went in, Jim explained the burial procedure practiced by most ancient Middle Eastern cultures: the deceased was wrapped in strips of cloth that were infused with spices to help cover unpleasant odors as the flesh began to decompose. The body was then laid in a cave or a hewn tomb for about a year, or until only the bones were left. (Sometimes worms were thrown in to help speed decomposition.) The dry bones were then removed and placed in an ossuary, a compact box that then could be stacked on top of others to make room for the next decedent. Although the current location of Lazarus’s tomb made it difficult for Michael to picture the scene when Jesus called, “Lazarus, come forth!” he could see why Christ had to use a loud voice, because even in the meridan of time, the burial chamber would have been down in the earth, below the level of the road.

Wine press at the tomb

When Nancy visited Lazarus’s tomb with her BYU group forty years ago, they walked the two miles from Jerusalem to Bethany along rough a dirt road. That road is now paved and outfitted with stairs to make it easier for tour groups to navigate. In 1976, a Palestinian family who lived across the street from the entrance to the tomb had made a little money by inviting tourists to visit their home, which consisted of a goathair lean-to in a small clearing surrounded by a low stone wall. Several children and a goat played in the clearing, which functioned as both living room and yard. A large clay water pot, a few bowls and baskets, and a short stack of folded blankets seemed to be their only possessions.

Judith bought slings for her seminary students

Today that Palestinian home has been replaced by a small souvenir shop, where Judith purchased several handmade woolen slings as gifts for the kids in her early-morning seminary class. The shop’s proprietor came outside, picked up a few stones, and demonstrated how David would have used a similar sling to slay Goliath.

Once everyone had had a turn to see the inside of Lazarus’s tomb, we hurried back to our hotel to drop off everything but our cameras so we would be ready to help usher in the sabbath at the Western Wall. As the sun began to set, we retraced the first steps we had taken through the Arab Quarter last night, but instead of turning up the Via Dolorosa, we continued south toward the other end of the Temple Mount. Soon we were caught up in the flow of religious Jews flocking to the Western Wall from their own quarter to observeshabbat. Many of the men wore traditional orthodox clothing: black calf-length coats and distinctive black fur hats. We had to pass through a security check at the gate, and then the men and women had to separate before entering their respective compounds next to the Wall–the only portion of the ancient temple still accessible to Jews for worship.

Michael at the Wall

Michael, like the other hatless men, was issued a simple white yarmulke to cover his head. As he approached the Wall, he sensed a heightened energy unlike that of any other place he has ever been. With the other Christian men is his group, he went into a corner of the covered area where they could share observations as they took in the experience. After a while, he felt comfortable enough to walk up to the Wall himself to offer prayer. He admits that it felt strange because the setting was an unfamiliar one, but he recognized the moment as significant and was glad that he had taken the opportunity. Although he did not feel any greater intimacy with God, he felt awe in a new way.

He also experienced a sense of brotherhood that was new to him. It was inspiring to observe groups of men singing and dancing joyfully together, and all the men in our group were delighted by the sight of a father chanting from the scrolls with his four young sons. Michael felt a closeness to his own group of pilgrims that he had not felt before, and shared with at least one of them the stirrings of his heart and his appreciation for him as a brother.

Worshippers line the Western Wall of the Temple Mount

Meanwhile, Nancy and the other women were making similar observations on the other side of the partition. Many fewer women than men were observing the sabbath at the Wall tonight, and those who had been here before said that there were many fewer congregants of either sex; perhaps recent violence in other parts of the country is making people more cautious about public religious gatherings. Unlike the men, the Jewish women who had come to worship seemed to be doing so as individuals rather than as groups. There was no singing and no dancing among the females, only reading and praying, and the mood was much more reverent than jubilant.

Written prayers wedged into the Western Wall

Nancy likewise took the opportunity to reverently approach the Western Wall and offer prayer in the form of a written request. This is unusual in LDS culture, although Mormons do have a tradition of placing the names of people with pressing needs on the altars of our own temples so they will be included in special prayers. Tonight, Nancy was thinking particularly of her 96-year-old father, who had broken his hip just two weeks ago, and of some other ailing members of her extended family. She had promised to remember them at this special place and ask for blessings of healing and comfort. While she knows that God will hear our prayers no matter how or where we offer them, she felt a sense of peace as she slipped her written prayer into a crevice between the blocks of the Wall and gave thanks for the opportunity to touch a part of the ancient House of God.

When our group regathered to return to our hotel for a sabbath meal, we walked a little more reverently and spoke a little more quietly as we shared our impressions with each other. The experience seemed to have made us feel a little more like brothers and sisters. And all of us expressed the hope that God would bless the people of this land with similar unity and peace.

Leave A Comment